Esther Shemitz

Esther Shemitz | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 25, 1900 New York City, US |

| Died | August 16, 1986 (aged 86) |

| Education | Rand School, Leonardo da Vinci Art School |

| Alma mater | Art Students League |

| Occupation(s) | Artist (painter), illustrator |

| Years active | 1925–1980 |

| Known for | Testified during Hiss Case |

| Spouse | Whittaker Chambers |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | Reuben Shemitz (brother), Nathan Levine (nephew), Sylvan Shemitz (nephew) |

| Website | whittakerchambers |

Esther Shemitz (June 25, 1900 – August 16, 1986), also known as "Esther Chambers" and "Mrs. Whittaker Chambers," was a pacifist American painter and illustrator who, as wife of ex-Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers, provided testimony that "helped substantiate" her husband's allegations during the Hiss Case.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Background[edit]

Shemitz was born on June 25, 1900, in New York City. She was the youngest child of Rabbi Benjamin Shemitz and Rose Thorner. The family soon moved from New York City to New Haven, Connecticut, where they ran a candy store.[7][8] The family had immigrated to the U.S. in the 1890s from the "Podolsk Province."[9]

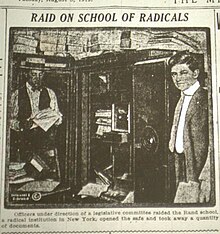

In the late 1910s, Shemitz attended the Rand School.[10] At Rand in the same period were Nerma Berman, the wife of the Soviet spy Cy Oggins, and CPUSA Fosterite Carrie Katz, the first wife of philosopher Sidney Hook.[11][12][13] In May 1920, Algernon Lee, educational director, presided over the graduation of the second-largest class ever at Rand, whose members included: John J. Bardsley, William D. Bavelaar, Annie S. Buller, Louis Cohan, Harry A. Durlauf, Clara Friedman, Rebecca Goldberg, William Greenspoon, Isabella E. Hall, Ammon A. Hennsey (Ammon Hennacy), Hedwig Holmes, Annie Kronhardt, Anna P. Lee, Victoria Levinson, Elsie Lindenberg, Selma Melms (first wife of Ammon Hennacy).[14]), Hyman Neback, Bertha Ruvinsky, Celia Samorodin, Mae Schiff, Esther T. Shemitz, Nathan S. Spivak, Esther Silverman, Sophia Ruderman, and Clara Walters.[15][10]

Career[edit]

Shemitz was a pacifist long before she met Chambers, though some sources call her a communist fellow traveler or "communist sympathizer" (e.g., Alistair Cooke), while many (e.g., Christopher Hitchens) are ambiguous on the subject.[16][17][18] [19][6][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Painter, illustrator[edit]

During the early 1920s, Shemitz worked at a chapter of the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union (ILGWU) under Juliet Stuart Poyntz in return for a stipend to the Leonardo da Vinci Art School.[20] On the night of April 5, 1922, "Esther T. Schemitz," described as "secretary-treasurer" of the ILGWU's Mount Vernon chapter, was arrested for disorderly conduct when she allegedly called a special police officer a "professional strike breaker." Shemitz was granted bail within two hours of jailing.[26]

In 1926, Shemitz roomed on East 11 Street on the Lower East Side with writer Grace Lumpkin, and they both worked at The World Tomorrow magazine.[20][27] During her time at the magazine, contributors included "social reformers, suffrage leaders, black intellectuals, labor activists, and a range of other progressives.[20] Shemitz also served as the advertising manager at the New Masses in 1926.[28][29][30] In December 1926, on behalf of the World Tomorrow, Shemitz took Rebecca West to see the Passaic Textile Strike at the Botany Worsted Mills. There Shemtiz was beaten and arrested along with Sophie Shulman of New Masses magazine and another reporter, Sender Garlin.[6][31][32][33]

In the latter 1920s, Shemitz studied at the Art Students League in New York under Boardman Robinson, Jan Matulka and Thomas Hart Benton. Shemitz also contributed cartoons to the Daily Worker newspaper.[20][34]

In 1929, Shemitz was one of many signatories to form the John Reed Club in New York. She illustrated books for International Publishers, notably Labor and Silk by Grace Hutchins (1929), with a cover designed by Louis Lozowick.[20][35]

At year-end 1929, Shemitz partook in the first-ever art exhibition of the John Reed Club, held at the United Workers Cooperatives apartment buildings (also called the "United Workers Cooperative Colony" and the "Commie Coops"[36]) on Bronx Park East. Artists in the show included: Jacob Burck, Fred Ellis, William Gropper, Eitaro Ishigaki, Gan Kolski, Louis Lozowick, Jan Matulka, Morris Pass, Anton Refregier, Louis Leon Ribak, Otto Soglow, and Art Young.[37]

In 1930, Shemitz worked briefly for the Soviet-controlled Amtorg Trading Corporation, AMTORG, a job found for her by Hutchin's partner Anna Rochester.[21][38]

In May 1930, Shemitz joined scores of artists, writers, and educators, all members of the John Reed Club, (at 102 West Fourteenth Street, New York) in signing a protest against "Red-baiting" protest. They included: Sherwood Anderson, Franz Boas, Walt Carmon, Malcolm Cowley, Floyd Dell, Carl Van Doren, John Dos Passos, Max Eastman, Fred Ellis, Kenneth Fearing, Waldo Frank, Harry Freeman, Hugo Gellert, Michael Gold, William Gropper, Jack Hardy, Josephine Herbst, Eitaro Ishigaki, Alfred Kreymborg, Joshua Kunitz, Louis Lozowick, A.B. Magil, H.L. Mencken, Scott Nearing, Joseph North, Isidore Schneider, Edwin Seaver, Edith Segal, Upton Sinclair, John Sloan, Raphael Soyer, Genevieve Taggard, Carlo Tresca, Louis Untermeyer, Edmund Wilson, and Art Young. At least one co-signer was a classmate (Jacob Burck), another a roommate (Grace Lumpkin), two were sponsors (Grace Hutchins and Anna Rochester), and two were teachers (Jan Matulka and Boardman Robinson).[39]

In April 1931, Shemitz married Whittaker Chambers. In May 1931, she contributed a cartoon to the New Masses magazine.[40] In 1932, when her husband's name appeared as an editor, the names of Esther Shemitz and Jacob Burck appeared as (art) contributors for the New Masses alongside longer-term contributors like Louis Lozowick, Hugo Gellert, William Gropper, William Siegel, and Joseph Vogel.[41]

Soviet underground[edit]

Shemitz cut short her own art career when her husband entered the Soviet underground in mid-1932. Thus, unlike most of her circle, who contributed to publications such as the Daily Worker newspaper and New Masses magazine, she did not become one of the New Deal's Federal Art Project artists during the latter part of the Great Depression and into World War II.

In 1938, when Chambers defected from the underground, Grace Hutchins delivered a death threat against him, through her brother, attorney Reuben Shemitz. Later, following a grand jury investigation in December 1948, Reuben Shemitz told the press:

(Hutchins) said she wanted to see him on a 'matter of life and death' ... She assured me that no harm would come to my sister or her children if Whit would get in touch with someone known to Whit as Steve (J. Peters).[42]

In his 1952 memoir, Chambers detailed:

There strode into my brother-in-law's office one morning a rather striking-looking white-haired woman, about fifty years old. She told the receptionist that Miss Grace Hutchins wished to see Mr. Shemitz ...

In his private office, she came to the point at once: "If you will agree to turn Chambers over to us," she said, "the party will guarantee the safety of your sister and the children." My startled brother-in-law, who, like most Americans, was completely unaware of what Communism is really like (we had never discussed the subject), tried to explain that he did not know even the whereabouts of his sister, her husband or their children ...

"If he does not show up by (such and such a day)," she said briskly, "he will be killed." with that she left ... Terrified by the visit and unable to warn us, he was frantic. He rushed to the only two people he could think of who might know where we were ... Neither of them could help him.[6]

. She managed the family's Pipe Creek Farm from the late 1930s to the mid-1950s.

Hiss Case[edit]

During deposition for the slander suit of Alger Hiss against Chambers in 1948, the Hiss legal team's rough treatment of Shemitz was the final factor in leading Chambers to disclose the existence of his "life preserver," which contained the "Baltimore Documents" and the "Pumpkin Papers."[citation needed] During the Hiss Case and trials, Shemitz corroborated and often augmented much of her husband's testimony.[citation needed] (She further explained, "I am now trying to remember things I had shut out of my mind, I thought completely."[43])

In December 1948, with indictments in the Hiss Case pending, Shemitz struck an elderly female pedestrian with her car; the woman soon died. The accident made front pages:

Sunday, December 19, 1948

HELD IN AUTO DEATH

Mrs. Whittaker Chambers, wife of the self-confessed former Communist spy, leaves the Baltimore police station after her arraignment in connection with the death of an aged woman struck by her car as she was going to the railroad station to pick up her husband after he testified before the Federal grand jury in Manhattan. Mrs. Chambers is the former Esther Shemitz of Brooklyn.[44]

Soon after, the case was dropped, as the victim had repeatedly attempted suicide by jumping in front of oncoming cars.[45]

Aftermath[edit]

Shemitz was subject to rumors from Hiss supporters, particularly one claiming that not only were she and Lumpkin lesbian lovers but they were also involved in a four-way menage with their allegedly gay husbands – most recently put forward in biography of lesbians Anna Rochester and Grace Hutchins.[38] In fact, Hutchins was the source of many such rumors: another she spread to the Hiss defense team was that Shemitz had told Hutchins that Chambers had spent time in the Westchester Division of the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum, a claim she later withdrew.[21] (Robert Cantwell, a close friend of Chambers, had received treatment there in the 1940s; "Robert Cantwell" was an alias Chambers had used in the Soviet underground.[46]) A.B. Magil (a long-time Daily Worker writer and editor and CPUSA member) told Elinor Ferry (a Hiss supporter) that Chambers' wife and her roommate Grace Lumpkin appeared to be lesbians. "Esther was masculine in appearance and in her voice. Grace was the softer, more feminine type."[47][48] The overall experience of the Hiss Case led Shemitz to avoid all press and never speak to researchers, including Allen Weinstein.[21]

Personal life and death[edit]

Shemitz's older brother was attorney Reuben Shemitz. A nephew was Nathan Levine; another was Sylvan Shemitz.

In 1926, Whittaker Chambers first saw Shemitz at the Passaic Textile Strike, which he described at length in his 1952 memoir.[6][4][20][21]

In 1930, Chambers and friend Mike Intrator began to court Shemitz and Lumpkin; both couples married in 1931. Shemitz's marriage was witnessed by Grace Hutchins and her life partner Anna Rochester. Shemitz and Chambers had a daughter in 1933 and a son in 1936.[4][20][21]

Once Chambers defected, husband and wife lived at the Pipe Creek Farm, near Westminster, Maryland, for the rest of their lives.[2][21] The couple had two children, Ellen and John, during the 1930s, despite the Communist leadership expecting couples to remain childless, but many refused, a choice Chambers cited as part of his gradual disillusionment with communism.[6] Daughter Ellen died in 2017; her children are Stephen, Pamela, and John.[49][50][51][52]

Shemitz made her first and only trip abroad, to Europe, with Chambers in the summer of 1959, during which they met Arthur Koestler and Margarete Buber-Neumann among others.[3][21]

When Chambers died of his seventh heart attack on July 9, 1961, Shemitz collapsed and was rushed to the nearest hospital in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[3][53] On August 16, 1986, she died age 86 at her home.[1][2]

Works[edit]

Paintings, illustrations[edit]

All of Shemitz's paintings are held privately by her family or friends. Her illustrations appeared in the Daily Worker newspaper, the New Masses magazine, and the book Labor and Silk and include:

- "Alookin' f'r a home," New Masses (May 1931)[54]

Books, articles[edit]

- "Creative Impulse in a Hostile Environment" with Grace Lumpkin, The World Tomorrow (April 1926)[55]

- Labor and Silk by Grace Hutchins, illustrations by Esther Shemitz, cover by Louis Lozowick (New York: International Publishers, 1929)[56][57]

- Cold Friday by Whittaker Chambers, edited by Duncan Norton-Taylor and Esther Shemitz (New York: Random House, 1964)[58]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Widow of Chambers Dies". The New York Times. 20 August 1986. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b c "Esther Shemitz Chambers; Widow of Man Who Played Key Role in Alger Hiss Case". Los Angeles Times. 23 August 1986. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b c "Chambers Is Dead; Hiss Case Witness". The New York Times. 12 July 1961. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b c "Historical Notes: Death of a Witness". Time. 21 July 1961. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Clara Database of Women Artists: Esther Shemitz Chambers". National Museum of Women in the Arts. 23 August 1986. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 48–50 (death threat), 232 (Passaic), 265 (courtship). ISBN 9780895269157. LCCN 52005149. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "The New Haven Jewish Cemetery Databse". New Haven Torah Center. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ Herman, Barry E.; Hirsch, Werner S. (1988). Jews in New Haven, Volume 5. Jewish Historical Society of New Haven. p. 126. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1964). Cold Friday. New York: Random House. pp. 281–284. ISBN 9780394419695. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Tenth Full-Time Class of Rand School Will be Graduated Tomorrow Night". The New York Call. 7 May 1920. p. 8. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Meier, Andrew (August 11, 2008). The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin's Secret Service. W. W. Norton. pp. 224–267, 289–300. ISBN 978-0-393-06097-3. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Hook, Sidney (1995). Edward S. Shapiro (ed.). Letters of Sidney Hook: Democracy, Communism, and the Cold War. M.E. Sharpe. p. 15.

- ^ Phelps, Christopher (2005). Young Sidney Hook: Marxist and Pragmatist. University of Michigan Press. pp. 33–34, 128.

- ^

Hennacy, Ammon (1965). The Book of Ammon. Hennacy.

daughter of the Socialist sheriff of Milwaukee, leader of the Yipsels, as the young Socialists were called, and secretary to the President of the State Federation of Labor

- ^ Watson, Louise. "She Never Was Afraid: The Biography of Annie Buller". Toronto: Progress Books. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Alistair Cooke (1952). A Generation on Trial: U.S.A. v. Alger Hiss. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-4976-3996-6. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Christopher Hitchens (2002). Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere. Verso. p. 119 (devoted Russian-born loyalist). ISBN 978-1-85984-383-3. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Joseph Kip Kosek (2011). Acts of Conscience: Christian Nonviolence and Modern American Democracy. Columbia University Press. p. 199 (Communist fellow traveler). ISBN 978-0-231-14419-3. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Glenn Peter Hastedt, ed. (2010). "Chambers, Whittaker". Spies, Wiretaps, and Secret Operations. Bloomsbury. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-85109-808-8. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lumpkin, Grace (1932). To Make My Bread. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. ix, xi (pacifist). ISBN 9780252065019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weinstein, Allen (1978). Perjury: The Hiss Chambers Case. New York: Random House. ISBN 9780817912260. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Christina Shelton (2012). Alger Hiss: Why He Chose Treason. Simon & Schuster. p. 95 (pacifist). ISBN 978-1-4516-5542-1. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Martin Roberts (2012). Secret History. AuthorHouse. p. 33 (pacifist). ISBN 978-1-4567-8986-2. Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Jerry Carrier (2017). A Long Cold War: A Chronology of American Life and Culture 1945 to 1991. Algora Publishing. p. 38 (pacifist). Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ Rebecca L. Davis (2021). Public Confessions: The Religious Conversions That Changed American Politics. UNC Press. p. 62 (pacifist). Retrieved 10 March 2024.

- ^ "Union Leader in Trouble with Special Officer". Mount Vernon, New York: Daily Argus. 6 April 1922. p. 1. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ Kosek, Joseph Kip (2011). Acts of Conscience: Christian Nonviolence and Modern American Democracy. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 199. ISBN 9780231144193.

- ^ "Masthead" (PDF). New Masses. June 1926. p. 3. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Masthead" (PDF). New Masses. July 1926. p. 3. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ "Masthead" (PDF). New Masses. August 1926. p. 3. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Nerone, John C. (1994). Violence Against the Press: Policing the Public Sphere in U.S. history. Oxford University Press. pp. 283]. ISBN 9780195071665. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Green, Archie (1993). Wobblies, Pile Butts, and Other Heroes: Laborlore Explorations. University of Illinois Press. p. 285. ISBN 9780252019630. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ Mantooth, Wes (2006). "You Factory Folks who Sing this Rhyme Will Surely Understand": Culture, Ideology, and Action in the Gastonia Novels of Myra Page, Grace Lumpkin, and Olive Dargan. Taylor & Francis. p. 59. ISBN 9780415977586. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- ^ "Boardman Robinson". Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^

Lincove, David A. (2004). "Radical Publishing to 'Reach the Million Masses': Alexander L. Trachtenberg and International Publishers, 1906–1966". Left History, vol. 10, no. hdl:1811/24792.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Kessler, Sarah (26 April 2009). "A Utopian Bronx Tale". Forward. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- ^

Hemingway, Andrew (2002). Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement, 1926-1956. Vol. 12. Yale University Press. pp. 47–48, 63, 67. ISBN 978-0-300-09220-2. JSTOR 1504057.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Allen, Julia M. (2013). Passionate Commitments: The Lives of Anna Rochester and Grace Hutchins. SUNY Press. pp. 151 (AMTORG), 152 (lesbianism). ISBN 9781438446899. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "'Red Scare' Protest Issued by Liberals: 100 Writers, Educators and Artists Warn of Dangers in 'Hysteria' and 'Persecution'". The New York Times. 19 May 1930. p. 18. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Shemitz, Esther (May 1931). "Alookin' f'r a Home" (PDF). New Masses. p. 11. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ^ "Masthead" (PDF). New Masses. June 1932. p. 3. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Boro Lawyer Tells of Part He Played in Threat to Chambers". Brooklyn Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 16 December 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ Berresford, John W. (1 June 2008). "'The Grand Jury in the Hiss-Chambers Case". American Communist History. 7 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1080/14743890802121878. S2CID 159487134.

- ^ "Held in Auto Death". Brooklyn Eagle. 19 December 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ^ Heidepriem, Scott (1988). A Fair Chance for a Free People: Biography of Karl E. Mundt, United States Senator. Leider Print. Co. p. 119. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Craig, R. Bruce (2001). "The Hiss-Chambers Controversy: Records of the House Un-American Activities Committee". The Alger Hiss Story: A Search for Truth. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ Zeligs, Meyer A. (1967). Friendship and fratricide; an analysis of Whittaker Chambers and Alger Hiss. New York: Viking. p. 105. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Allen, Julia M. (2013). Passionate Commitments: The Lives of Anna Rochester and Grace Hutchins. SUNY Press. p. 152. ISBN 9781438446899. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ^ "Dr. Ellen Chambers Into". Thomas Funeral Home. 2017. Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Dr. Ellen Chambers Into". Baltimore Sun. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Dr. Ellen Chambers Into". San Francisco Chronicle. 3 December 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Ellen Chambers". Carroll County Times. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ "Whittaker Chambers, Key Witness In AlgerHissCase, Dies; Wife Critical Here". The Gettysburg Times. 12 July 1961. p. 1. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ Shemitz, Esther (May 1931). "Alookin' f'r a home" (PDF). New Masses: 11. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Charles Spurgeon (1969). Opportunity. National Urban League. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ Hutchins, Grace (1929). "illustrations (Esther Shemitz)". Labor and Silk. New York: International Publishers. LCCN 29008933.

- ^ Blanc, Paul David (15 November 2016). Fake Silk: The Lethal History of Viscose Rayon. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300224887. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (1964). Cold Friday. New York: Random House. LCCN 64020025.

External sources[edit]

- "Widow of Chambers Dies". The New York Times. 20 August 1986. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- "Esther Shemitz Chambers; Widow of Man Who Played Key Role in Alger Hiss Case". Los Angeles Times. 23 August 1986. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Chambers, Whittaker (1952). Witness. New York: Random House. pp. 48–50 (death threat), 232 (Passaic), 265 (courtship). ISBN 9780895269157. LCCN 52005149. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "Clara Database of Women Artists: Esther Shemitz Chambers". National Museum of Women in the Arts. 23 August 1986. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Hathi Trust: Labor and Silk

- 1900 births

- 1986 deaths

- American pacifists

- American people of Ukrainian-Jewish descent

- American editorial cartoonists

- 20th-century American Jews

- Art Students League of New York alumni

- Jewish pacifists

- Jewish socialists

- Jewish women painters

- Jewish painters

- Painters from New York City

- Painters from Maryland

- 20th-century American women painters

- 20th-century American painters