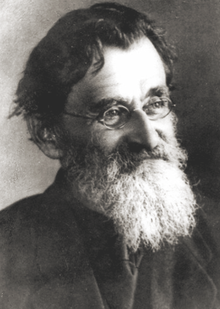

Feliks Kon

Feliks Kon Феликс Яковлевич Кон | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader of Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine temporarily | |

| In office March 22, 1921 – December 14, 1921 | |

| Preceded by | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Succeeded by | Dmitriy Manuilsky |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 18, 1864 Warsaw, Russian Empire |

| Died | July 28, 1941 (aged 77) Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Alma mater | University of Warsaw |

Feliks Yakovlevich Kon (May 18, 1864 – July 30, 1941) was a Polish communist activist.

Career

Born in Warsaw, Kon's mother was Georgian Jewish and was brought up in Russia.[1] He was trained as a historian and a journalist, but was involved in politics.[2] He had limited knowledge of Polish affairs at first, but intuitively felt the revolutionary element among Polish workers that he could mobilize.[1]

He was a member of the anti-Piłsudski faction of the Polish Socialist Party. Kon gravitated towards the anti-independence, pro-communism point of view. In January 1897 an administrative decision was at last taken to banish him.[3] He was exiled to Irkutsk and began working on the progressive newspaper "Vostochnoye Obozrenie" (Eastern Review).[4]

As the Bolsheviks began to prepare for the Polish-Soviet War, they summoned an increasing number of Polish communists, active elsewhere in Soviet service, to Moscow in order to form a cadre of party and state officials to move into ethnographic Poland with the Red Army.[5] He was put on the Provisional Polish Revolutionary Committee (formed in Białystok on July 30, 1920 - dissolved August 20, 1920)[6] during the Polish-Soviet War.

During this period he was editor-in-chief of the Goniec Czerwony newspaper, the official organ of the temporary revolutionary committee. The first issue appeared on August 7. Its purpose was to agitate and it printed all the appeals issued by the Communist puppet government, as well as distinctly skewed news from the war. Twelve issues appeared, the last on August 20 as the Polish army approached the city. In the last issue he triumphantly proclaimed in an article entitled "Dwa światy" (Two Worlds): The old world disappears, but a new one is born: great, powerful and a genuinely independent Polish Socialist Republic will hold the prominent post in this world.[7]

After the war, he decided to remain in the Soviet Union, where he was an activist in the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine, Comintern. However, letters written by Vladimir Lenin referred to Kon, whom he "couldn't stand", as simply an "old fool" (staryi duren).[8]

Kon also served as an editor at several newspapers including Krasnaya Zvezda. In 1941, he became the director of the Polish-directed propaganda section at Radio Moscow. The first broadcasts in Polish were on June 22, 1941. However, he died a natural death shortly afterwards at age 77, at Moscow's Khimki water station during the evacuation of the city before the advancing German army and the Battle of Moscow.[9] All the other members of the Polish Socialist Party-Left were later liquidated by the NKVD.[10]

Arts

During his exile for revolutionary activity turned to ethnographic research although he had no preparation for it. He also recorded literature possessions in Siberia.[11]

During the late 1920s and 1930s, he was the head of the museum department in the People's Commissariat for Education. As an "old Bolshevik" he managed to secure many pictures for the Kyrgyz Gallery.[12]

In 1936, he published his memoirs (in Russian) entitled Za Pietdziesiat Let (also translated into Polish in 1969: Narodziny wieku – wspomnienia published by Książka i Wiedza).

Ship

A Russian sea vessel named in his honor, the Feliks Kon, sank in 1996 in the Sea of Okhotsk, releasing 1000 tons of fuel oil.[13]

Notes

- ^ a b Nowicki, Michał. "Stanisław Kunicki w polskiej historiografii" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 23 February 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Jewish Encyclopedia of Russia (Rossiyskaya Evreiskaya Entsiclopediya); first edition". Moscow. 1995. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Savel'ev, P. Iu.; Tiutiukin, S. V. (Summer 2006). "Iulii Osipovich Martov (1873-1923): The Man and the Politician". Russian Studies in History. 45 (1): 6–92. doi:10.2753/RSH1061-1983450101.

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Alexandr I. (1974). The Gulag Archipelago, 1918-1956. HarperCollins. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-06-013914-8.

- ^ Debo, Richard K. (1992). Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921. McGill-Queen's Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-7735-0828-6.

- ^ Cahoon, Ben. "Poland Chronology (Polish Soviet Socialist Republic)". worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Przemysław Sieradzan Julian Marchlewski i Krótka Historia Polskiego Rewolucyjnego Komitetu" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 9 August 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Elwood, Carter (March 2001). "Lenin and Armand: New evidence on an old affair". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 43 (1): 49–65. JSTOR 40870275.

- ^ "Radio Voice of Russia - History of the Polish broadcasts" (in Polish). Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Poland's Communist Party: Its History, Character and Composition". Open Society Archives at Central European University. pp. 2–3. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Michałowski, Witold Stanisław (30 January 2011). "Szamańskie safari (2)" (in Polish). Fundacja Wolnej Myśli. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Brief information about the history of the Fine Arts Museum and the founders of fine arts in Kyrgyzstan". apms.kg. Archived from the original on 2 February 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ "Environmental Problems in the Russian Federation" (PDF). Foreign & Commonwealth Office. October 2000. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

References

- Blit, Lucjan (1971). The Origins of Polish Socialism: The History and Ideas of the First Polish Socialist Party, 1878–1886. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08968-5.

- Deutscher, Tamara. "Introduction" (PDF). pp. 133 and 160. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- Leinwand, A. J. (2005). "The Agitation and Propaganda Activity of Polish Communists in the Russian Socialist Federal Soviet Republic in 1918-1920". Studia z Dziejow Rosji i Europy Srodkowo-Wschodniej (Studies in the History of Russia and Central-Eastern Europe). 40: 25–61. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2014.