Frankenstein's monster

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

| Frankenstein's monster | |

|---|---|

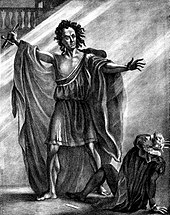

Steel engraving (993 × 78 mm), for the frontispiece of the 1831 revised edition of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, published by Colburn and Bentley, London. | |

| First appearance | Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus |

| Created by | Mary Shelley |

| In-universe information | |

| Nickname | "Frankenstein", "The Monster", "The Creature", "The Wretch", "Adam Frankenstein" and others |

| Species | Simulacrum human |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Victor Frankenstein (creator) Bride of Frankenstein (companion/predecessor; in different adaptions) |

Frankenstein's monster, often erroneously referred to as "Frankenstein", is a fictional character who first appeared in Mary Shelley's 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Shelley's title thus compares the monster's creator, Victor Frankenstein, to the mythological character Prometheus, who fashioned humans out of clay and gave them fire.

In Shelley's Gothic story, Victor Frankenstein builds the creature in his laboratory through an ambiguous method consisting of chemistry and alchemy. Shelley describes the monster as 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) and hideously ugly, but sensitive and emotional. The monster attempts to fit into human society but is shunned, which leads him to seek revenge against Frankenstein. According to the scholar Joseph Carroll, the monster occupies "a border territory between the characteristics that typically define protagonists and antagonists".[1]

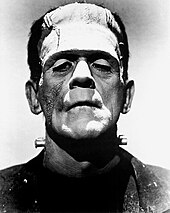

Frankenstein's monster became iconic in popular culture, and has been featured in various forms of media, like films, television series, merchandise and video games. His most iconic version is his portrayal by Boris Karloff in the 1931 film Frankenstein.

Names

Mary Shelley's original novel never ascribes an actual name to the monster; although when speaking to his creator, Victor Frankenstein, the monster does say "I ought to be thy Adam" (in reference to the first man created in the Bible). Frankenstein refers to his creation as "creature", "fiend", "spectre", "the demon", "wretch", "devil", "thing", "being", and "ogre".[2] Frankenstein's creation did at least once refer to himself as a "monster" as did other villagers towards the end of the novel.

It has become common to refer to the creature by the name "Frankenstein" or "The Monster" but neither of these names are as apparent in the book.[3]

As in Shelley's story, the creature's namelessness became a central part of the stage adaptations in London and Paris during the decades after the novel's first appearance. In 1823, Shelley herself attended a performance of Richard Brinsley Peake's Presumption, the first successful stage adaptation of her novel. "The play bill amused me extremely, for in the list of dramatis personae came _________, by Mr T. Cooke," she wrote to her friend Leigh Hunt. "This nameless mode of naming the unnameable is rather good."[4]

Within a decade of publication, the name of the creator—Frankenstein—was used to refer to the creature, but it did not become firmly established until much later. The story was adapted for the stage in 1927 by Peggy Webling,[5] and Webling's Victor Frankenstein does give the creature his name. However, the creature has no name in the Universal film series starring Boris Karloff during the 1930s, which was largely based upon Webling's play.[6] The 1931 Universal film treated the creature's identity in a similar way as Shelley's novel: in the opening credits, the character is referred to merely as "The Monster" (the actor's name is replaced by a question mark, but Karloff is listed in the closing credits).[7] Nevertheless, the creature soon enough became best known in the popular imagination as "Frankenstein". This usage is sometimes considered erroneous, but some usage commentators regard the monster sense of "Frankenstein" as well-established and not an error.[8][9]

Modern practice varies somewhat. For example, in Dean Koontz's Frankenstein, first published in 2004, the creature is named "Deucalion", after the character from Greek Mythology, who is the son of the titan Prometheus, a reference to the original novel's title. Another example is the second episode of Showtime's Penny Dreadful, which first aired in 2014; Victor Frankenstein briefly considers naming his creation "Adam", before deciding instead to let the monster "pick his own name". Thumbing through a book of the works of William Shakespeare, the monster chooses "Proteus" from The Two Gentlemen of Verona. It is later revealed that Proteus is actually the second monster Frankenstein has created, with the first, abandoned creation having been named "Caliban", from The Tempest, by the theatre actor who took him in and later, after leaving the theatre, named himself after the English poet John Clare.[10]

Shelley's plot

As told by Mary Shelley, Victor Frankenstein builds the creature in the attic of his boarding house through an ambiguously described scientific method consisting of chemistry (from his time as a student at University of Ingolstadt) and alchemy (largely based on the writings of Paracelsus, Albertus Magnus, and Cornelius Agrippa). Frankenstein is disgusted by his creation, however, and flees from it in horror. Frightened, and unaware of his own identity, the monster wanders through the wilderness.

He finds brief solace beside a remote cottage inhabited by a family of peasants. Eavesdropping, the creature familiarizes himself with their lives and learns to speak, whereby he becomes eloquent, educated, and well-mannered. The creature eventually introduces himself to the family's blind father, who treats him with kindness. When the rest of the family returns, however, they are frightened of him and drive him away. Hopeful but bewildered, the creature rescues a peasant girl from a river but is shot in the shoulder by a man who claims her. He finds Frankenstein's journal in the pocket of the jacket he found in the laboratory, and swears revenge on his creator for leaving him alone in a world that hates him.

The monster kills Victor's younger brother William upon learning of the boy's relation to his hated creator. When Frankenstein retreats to the mountains, the monster approaches him at the summit and asks his creator to build him a female mate. In return, he promises to disappear with his mate and never trouble humankind again; the monster then threatens to destroy everything Frankenstein holds dear should he fail or refuse. Frankenstein agrees and builds a female creature, but, aghast at the possibility of creating a race of monsters, destroys his experiment. In response, the monster kills Frankenstein's best friend Henry Clerval, and later kills Frankenstein's bride Elizabeth Lavenza on their wedding night, whereupon Frankenstein's father dies of grief. With nothing left to live for but revenge, Frankenstein dedicates himself to destroying his creation.

Searching for the monster in the Arctic Circle, Frankenstein falls into the freezing water, contracting severe pneumonia. A ship exploring the region encounters the dying Frankenstein, who relates his story to the ship's captain, Robert Walton. Later, the monster boards the ship; but, upon finding Frankenstein dead, is overcome by grief and pledges to incinerate himself at "the Northernmost extremity of the globe". He then departs, never to be seen again.

Appearance

Shelley described Frankenstein's monster as an 8-foot-tall (2.4 m) creature of hideous contrasts:

His limbs were in proportion, and I had selected his features as beautiful. Beautiful! Great God! His yellow skin scarcely covered the work of muscles and arteries beneath; his hair was of a lustrous black, and flowing; his teeth of a pearly whiteness; but these luxuriances only formed a more horrid contrast with his watery eyes, that seemed almost of the same colour as the dun-white sockets in which they were set, his shrivelled complexion and straight black lips.

A picture of the creature appeared in the 1831 edition. Early stage portrayals dressed him in a toga, shaded, along with the monster's skin, a pale blue. Throughout the 19th century, the monster's image remained variable according to the artist.

The best-known image of Frankenstein's monster in popular culture derives from Boris Karloff's portrayal in the 1931 movie Frankenstein, in which he wore makeup applied, and according to a format designed by, Jack P. Pierce and possibly suggested by director James Whale. Universal Studios, which released the film, was quick to secure ownership of the copyright for the makeup format. Karloff played the monster in two more Universal films, Bride of Frankenstein and Son of Frankenstein; Lon Chaney Jr. took over the part from Karloff in The Ghost of Frankenstein; Bela Lugosi portrayed the role in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man; and Glenn Strange played the monster in the last three Universal Studios films to feature the character – House of Frankenstein, House of Dracula, and Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. But their makeup replicated the iconic look first worn by Karloff. To this day, the image of Karloff's face is owned by his daughter's company, Karloff Enterprises, for which Universal replaced Karloff's features with Glenn Strange's in most of their marketing.

Since Karloff's portrayal, the creature almost always appears as a towering, undead-like figure, often with a flat-topped angular head and bolts on his neck to serve as electrical connectors or grotesque electrodes. He wears a dark, usually tattered, suit having shortened coat sleeves and thick, heavy boots, causing him to walk with an awkward, stiff-legged gait (as opposed to the novel, in which he is described as much more flexible than a human). The tone of his skin varies (although shades of green or gray are common), and his body appears stitched together at certain parts (such as around the neck and joints). This image has influenced the creation of other fictional characters, such as the Hulk.[11]

In the 1973 TV miniseries Frankenstein: The True Story, a different approach was taken in depicting the monster: Michael Sarrazin appears as a strikingly handsome man who later degenerates into a grotesque monster due to a flaw in the creation process.

In the 1994 film Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the creature is played by Robert De Niro in a nearer approach to the original source, except this version gives the creature balding grey hair and a body covered in bloody stitches. He is, as in the novel, motivated by pain and loneliness. In this version, Frankenstein gives the monster the brain of his mentor, Doctor Waldman, while his body is made from a man who killed Waldman while resisting a vaccination. The monster retains Waldman's "trace memories" that apparently help him quickly learn to speak and read.

In the 2004 film Van Helsing, the monster is shown in a modernized version of the Karloff design. He is 8 to 9 feet (240–270 cm) tall, has a square bald head, gruesome scars, and pale green skin. The electricity is emphasized with one electrified dome in the back of his head and another over his heart. It also has hydraulic pistons in its legs, essentially rendering the design as a steam-punk cyborg. Although not as eloquent as in the novel, this version of the creature is intelligent and relatively nonviolent.

In 2004, a TV miniseries adaptation of Frankenstein was made by Hallmark. Luke Goss plays The Creature. This adaptation more closely resembles the monster as described in the novel: intelligent and articulate, with flowing, dark hair and watery eyes.

The 2014 TV series Penny Dreadful also rejects the Karloff design in favor of Shelley's description. This version of the creature has the flowing dark hair described by Shelley, although he departs from her description by having pale grey skin and obvious scars along the right side of his face. In this series, the monster names himself "Caliban", after the character in William Shakespeare's The Tempest. In the series, Victor Frankenstein makes a second and third creature, each more indistinguishable from normal human beings.

Personality

As depicted by Shelley, the monster is a sensitive, emotional creature whose only aim is to share his life with another sentient being like himself. The novel and film versions portrayed him as versed in Paradise Lost, Plutarch's Lives, and The Sorrows of Young Werther.

From the beginning, the monster is rejected by everyone he meets. He realizes from the moment of his "birth" that even his own creator cannot stand the sight of him; this is obvious when Frankenstein says "…one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped…".[12]: Ch.5 Upon seeing his own reflection, he realizes that he too is repulsed by his appearance. His greatest desire is to find love and acceptance; but when that desire is denied, he swears revenge on his creator.

Contrary to many film versions, the creature in the novel is very articulate and eloquent in his way of speaking. Almost immediately after his creation, he dresses himself; and within 11 months, he can speak and read German and French. By the end of the novel, the creature appears able to speak English fluently as well. The Van Helsing and Penny Dreadful interpretations of the character have similar personalities to the literary original, although the latter version is the only one to retain the character's violent reactions to rejection.

In the 1931 film adaptation, the monster is depicted as mute and bestial; it is implied that this is because he is accidentally implanted with a criminal's "abnormal" brain. In the subsequent sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, the monster learns to speak, albeit in short, stunted sentences. In the second sequel, Son of Frankenstein, the creature is again rendered inarticulate. Following a brain transplant in the third sequel, The Ghost of Frankenstein, the monster speaks with the voice and personality of the brain donor. This was continued after a fashion in the scripting for the fourth sequel, Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man, but the dialogue was excised before release. The monster was effectively mute in later sequels, though he is heard to refer to Count Dracula as his "master" in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. The monster is often portrayed as being afraid of fire.

The monster as a metaphor

Scholars sometimes look for deeper meaning in Shelley's story, and have analogized the monster to a motherless child; Shelley's own mother died while giving birth to her.[13] The monster has also been analogized to an oppressed class; Shelley wrote that the monster recognized "the division of property, of immense wealth and squalid poverty."[13] Others see in the monster the tragic results of uncontrolled scientific progress,[14] especially as at the time of publishing, Galvanism had convinced many scientists that raising the dead through use of electrical currents was a scientific possibility.

Another proposal is that the character of Dr. Frankenstein was based upon a real scientist who had a similar name, and who had been called a modern Prometheus – Benjamin Franklin. Accordingly, the monster would represent the new nation that Franklin helped to create out of remnants left by England.[15] Victor Frankenstein's father "made also a kite, with a wire and string, which drew down that fluid from the clouds," wrote Shelley, similar to Franklin's famous kite experiment.[15]

Portrayals

Appearances in other media

- Frankenstein's Monster has appeared in some Looney Tunes cartoons:

- A robotic version of Frankenstein's Monster appears in the cartoon short Dr. Devil and Mr. Hare. He ends up beating up the Tasmanian Devil and then beats up his creator Bugs Bunny.

- Frankenstein's Monster appears in The Night of the Living Duck. He is seen in Daffy Duck's dream among the monsters in the nightclub that Daffy is in and is accompanied by his bride.

- A Stone Age version of Frankenstein's monster appears in various Flintstones media, named Frankenstone, Frankenstone monster, or Frank Frankenstone where he is voiced by Ted Cassidy in The Flintstones Meet Rockula and Frankenstone, John Stephenson in The New Fred and Barney Show and The Flintstones' New Neighbors, and by Charles Nelson Reilly in The Flintstone Comedy Show. He first appears in The Flintstones Meet Rockula and Frankenstone as a minion of Count Rockula. In The New Fred and Barney Show episode "Fred and Barney Meet the Frankenstones," Frank Frankenstone and his family live in the Condominium Spa where Count Rockula also resides. In The Flintstones' New Neighbors, Frank Frankenstone and his family becomes the neighbor to the Flintstones. In The Flintstone Comedy Show, Frank Frankenstone is shown to develop a rivalry with Fred Flintstone.

- Marvel Comics has its adaptation of Frankenstein's Monster and its various clones.

- DC Comics has its adaptation of Frankenstein and also featured Young Frankenstein.

- The eponymous creature in Stephen King's It takes the form of the Boris Karloff incarnation of Frankenstein's monster at one point.

- The Creature is a recurring boss in Konami’s Castlevania series of video games.

- In Super Sentai, some of the monsters are modeled after Frankenstein's monster.

- In Kyoryu Sentai Zyuranger, the monster Dora Franke is modeled after Frankenstein's Monster and has a second form called Zombie Franke and a third form called Satan Franke. The monsters were adapted in Mighty Morphin Power Rangers as separate monsters Frankenstein Monster and Mutitus.

- In Mahou Sentai Magiranger, Victory General Branken is a cyborg monster that is inspired by Frankenstein's Monster. He is adapted in Power Rangers Mystic Force as Morticon.

- In Shuriken Sentai Ninninger, the Western Yokai Franken is a Frankenstein's monster/flashlight monster that is one of the Western Yokai associated with the Kibaoni Army Corps. It was adapted in Power Rangers Ninja Steel as Deceptron.

- Lego has its adaptations of Frankenstein's Monster:

- Frankenstein's Monster appears in Series 4 of Lego Minifigures as "The Monster" where he was created by the Crazy Scientist (who was also in the same Minifigure series). The Monster was also playable in Lego City Undercover. Series 14 features the "Horror Rocker" who is a rock music version of Frankenstein's Monster.

- In Lego Monster Fighters, another adaptation of Frankenstein's Monster appeared as the "Crazy Scientist's Monster" where he was built by a Crazy Scientist that was associated with the same Lego theme. There is also a related monster in this theme called the "Monster Butler" who works for Lord Vampyre at his haunted house.

- Frankenstein's Monster appears in Fables. Outside of his creation at the hands of Victor Frankenstein, he is later reanimated by the Nazis during World War II, and he fights protagonist Bigby Wolfe. His still-animated head is kept in the business offices in the Woodlands.

- Frankenstein's Monster appears in the light novel Fate/Apocrypha voiced by Ai Nonaka in the Japanese version and by Sarah Anne Williams in the English dub. Frankenstein's Monster appears as a servant of the Berserker class and is depicted as a young girl. She also appears in another installment of the series Fate/Grand Order.

See also

- Frankenstein in popular culture

- List of films featuring Frankenstein's monster

- Allotransplantation, the transplantation of body parts from one person to another

References

- ^ Carroll, Joseph; Gottschall, Jonathan; Johnson, John A.; Kruger, Daniel J. (2012). Graphing Jane Austen: The Evolutionary Basis of Literary Meaning. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137002402.

- ^ Baldick, Chris (1987). In Frankenstein's shadow: myth, monstrosity, and nineteenth-century writing. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198117261. ISBN 0198117264.

- ^ Ja, Stewart (November 27, 2015). "10 Facts You Need To Know About Frankenstein (And His Monster)". Screen Rant. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Haggerty, George E. (1989). Gothic Fiction/Gothic Form. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0271006451.

- ^ Hitchcock, Susan Tyler (2007). Frankenstein: a cultural history. New York City: W. W. Norton. ISBN 9780393061444.

- ^ Young, William; Young, Nancy; Butt, John J. (2002). The 1930s. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 199. ISBN 978-0313316029.

- ^ Schor, Esther (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0521007702.

- ^ Evans, Bergen (1962). Comfortable Words. New York City: Random House.

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (1998). A dictionary of modern American usage. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195078534.

- ^ Crow, Dennis (October 19, 2016). "Penny Dreadful: The Most Faithful Version of the Frankenstein Legend". Den of Geek. London, England: Dennis Publishing. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Weinstein, Simcha (2006). Up, Up, and Oy Vey!: how Jewish history, culture, and values shaped the comic book superhero. Baltimore, Maryland: Leviathan Press. pp. 82–97. ISBN 978-1-881927-32-7.

- ^ Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft (1818). "Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus". Retrieved 3 November 2012 – via Gutenberg Project.

- ^ a b Milner, Andrew (2005). Literature, Culture and Society. New York City: NYU Press. pp. 227, 230. ISBN 978-0814755648.

- ^ Coghill, Jeff (2000). CliffsNotes on Shelley's Frankenstein. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 30. ISBN 978-0764585937.

- ^ a b Young, Elizabeth (2008). Black Frankenstein: The Making of an American Metaphor. New York City: NYU Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0814797150.

- ^ Chaney also reprised the role, uncredited, for a sequence in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein due to the character's assigned actor, Glenn Strange being injured.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Paul Simon: 12/19/87: Succinctly Speaking".

- ^ "Watch Weekend Update: Frankenstein on Congressional Budget Cuts from Saturday Night Live on NBC.com".

- ^ "A Nightmare On Lime Street – Royal Court Theatre Liverpool".

External links

- Fictional child killers

- Characters in British novels of the 19th century

- Fictional characters introduced in 1818

- Fictional characters without a name

- Fictional characters with superhuman strength

- Fictional murderers

- Fictional suicides

- Fictional undead

- Frankenstein characters

- Male horror film villains

- Male characters in film

- Male characters in literature

- Fictional monsters

- Once Upon a Time (TV series) characters

- Hotel Transylvania characters

- Toho Monsters

- Male literary villains

- Godzilla characters