Freddie Mercury: Difference between revisions

Avicennasis (talk | contribs) m Cleanup per Category:Wikipedia pages with incorrect protection templates. You can help! |

Tag: section blanking |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

{{Main|Freddie Mercury discography}} |

{{Main|Freddie Mercury discography}} |

||

{{See also|Queen discography}} |

{{See also|Queen discography}} |

||

=== Studio albums === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:100%;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!align="left"|Album information |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[Mr. Bad Guy]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 29 April 1985 |

|||

* Chart positions: United Kingdom #6; Germany #11; Norway #13; Switzerland #14; Japan, Netherlands; Sweden #20; Austria # 23, #159 United States |

|||

* Singles: "[[I Was Born to Love You (song)|I Was Born to Love You]]", "Made in Heaven", "[[Living on My Own]]", "Love Me Like There's No Tomorrow". |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[Barcelona (album)|Barcelona]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 10 October 1988 |

|||

* Chart positions: United States #6; Netherlands #9; United Kingdom #15; Switzerland #18; Austria #24; Sweden #37; Germany #41; Japan #93. |

|||

* Singles: "Barcelona", "The Golden Boy", "How Can I Go On". |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Compilation albums === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:100%;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!align="left"|Album information |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[The Freddie Mercury Album]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 16 November 1992 |

|||

* Chart positions: #1: Italy; #2 Austria; #3 Germany; #4 UK; #5 France; #8 Netherlands, Switzerland; #12 Norway; #20 Netherland; #35 Sweden; #64 Japan. |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''Remixes''''' |

|||

* Released: 1993 |

|||

* Chart positions: #18 Switzerland; #22 Germany; #25 Austria. |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[The Great Pretender (Freddie Mercury album)|The Great Pretender]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 24 November 1992 (U.S.) |

|||

* Chart positions: #13 France; #14 Sweden; #15 Switzerland; #26 Austria. |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[The Solo Collection|Solo]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 2000 |

|||

* Chart positions: #13 UK; #21 Netherlands; #36 Austria; #42 Switzerland; #55 Germany. |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[Lover of Life, Singer of Songs|Lover of Life, Singer of Songs — The Very Best of Freddie Mercury Solo]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 4 September 2006 |

|||

* Chart positions: #1: Italy 1; #6: Spain, United Kingdom (gold); #7 Austria; #8: Norway; #9: Hungary; #11: Portugal; #13: Germany; #14: France, Mexico, Sweden; #16 Switzerland; #26: Ireland; #30: Netherlands; #55: Finland; #60: Denmark; #65: Japan; #69: Belgium. |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Box Set === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="width:100%;" |

|||

|- |

|||

!align="left"|Album information |

|||

|- |

|||

|align="left"|'''''[[The Solo Collection]]''''' |

|||

* Released: 23 October 2000 |

|||

* Chart positions: |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Singles === |

|||

* ''[[Love Kills]]'' (co-written with [[Giorgio Moroder]]; Used on the soundtrack for the 1984 reissue of ''[[Metropolis (film)|Metropolis]]'') (1984) UK #10 |

|||

* ''[[I Was Born to Love You (song)|I Was Born to Love You]]'' (1985) UK #11, US #76 |

|||

* ''Made in Heaven'' (1985) UK #57 |

|||

* ''[[Living on My Own]]'' (1985) UK #50 |

|||

* ''Love Me Like There's No Tomorrow'' (1985) UK #76 |

|||

* ''Time'' (1986) UK #32 |

|||

* ''[[The Great Pretender]]'' (1987, re-released 1993) UK #4, France #16 |

|||

* ''[[Barcelona (song)|Barcelona]]'' (with [[Montserrat Caballé]]) (1987) UK #8 |

|||

* ''The Golden Boy'' (with [[Montserrat Caballé]]) (1988) UK #86 |

|||

* ''How Can I Go On'' (with [[Montserrat Caballé]]) (1989, re-released 1992) UK #95 |

|||

* ''Barcelona'' (with [[Montserrat Caballé]]) (reissue) (1992) UK #2, France #10 |

|||

* ''In My Defence'' (1992) UK #8, France #74 |

|||

* ''The Great Pretender'' (reissue) (1993) UK #29 |

|||

* ''Living on My Own'' (No More Brothers remix, 1993) UK #1 (2 weeks), France #1 |

|||

* ''Love Kills'' (Sunshine People Remixes, 2006) |

|||

=== Collaborations and guest appearances === |

|||

* 1973 "I Can Hear Music" / "[[Goin' Back]]" by [[Larry Lurex]] piano and lead vocals. |

|||

* 1975 All four members of Queen helped produce a session with the soul band Trax. Nothing was ever released. |

|||

* 1976 "Man From Manhattan" by Eddie Howell played piano and produced this track. |

|||

* 1976 "You Nearly Did Me In" by [[Ian Hunter (singer)|Ian Hunter]] backing vocals on this song, from the album "All-American Alien Boy". |

|||

* 1978 "This One's On Me" by Peter Straker backing vocals and co-produced this album with [[Roy Thomas Baker]]. |

|||

* 1982 "Emotions in Motion" by [[Billy Squier]] backing vocals on this song, from album of same name. Also on the 1996 Billy Squier anthology "Reach For The Sky". |

|||

* 1983 "Victory", "There Must Be More To Life Than This" and "State of Shock" were recorded by Freddie and [[Michael Jackson]], but never released. |

|||

* 1986 "Love Is The Hero" by Billy Squier backing vocals on this song from the album "Enough Is Enough". Freddie sings the intro on the 12" single. also co-wrote and co-produced track "Lady With a Tenor Sax", from the same album Both also on the 1996 Billy Squier anthology "Reach For The Sky". |

|||

* 1986 "Hold On" duet with Jo Dare co-wrote this song from the German soundtrack of "Zabou". |

|||

* 1988 "Heaven For Everyone" by [[The Cross]] lead vocals on the LP version, backing vocals on the single version (or the version on the US album) from the album "Shove It". |

|||

* 1994 "Man From Manhattan" by Eddie Howell played piano and produced this re-released single from the album of the same name. |

|||

== Notes == |

== Notes == |

||

Revision as of 23:45, 17 June 2010

Freddie Mercury |

|---|

Freddie Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara (Gujarati: ફ્રારુક બુલ્સારા), 5 September 1946 – 24 November 1991)[4] was a British musician, best known as the lead vocalist of the rock band Queen. As a performer, he was known for his flamboyant stage persona and powerful vocals over a four-octave range.[5][6][7] As a songwriter, Mercury composed many hits, including "Bohemian Rhapsody", "Killer Queen", "Somebody to Love", "Don't Stop Me Now", "Crazy Little Thing Called Love", "We Are the Champions" and "Barcelona". In addition to his work with Queen, he also led a solo career and was occasionally a producer and guest musician (piano or vocals) for other artists.

Mercury, who was a Parsi born in Zanzibar and who grew up there and in India until his mid-teens, has been referred to as "Britain's first Asian rock star".[8] He died of bronchopneumonia brought on by AIDS on 24 November 1991, only one day after publicly acknowledging he had the disease. In 2006, Time Asia named him as one of the most influential Asian heroes of the past 60 years,[9] and he continues to be voted one of the greatest singers in the history of popular music. In 2005, a poll organised by Blender and MTV2 saw Mercury voted the greatest male singer of all time.[10] In 2009, a Classic Rock poll saw him voted the greatest rock singer of all time.[11] In 2008, Rolling Stone editors ranked him number 18 on their list of the 100 greatest singers of all time.[6] Allmusic has characterised Mercury as "one of the most dynamic and charismatic frontmen in rock history."[12] Hit Parader ranked Mercury as the sixth greatest heavy metal singer of all time[4].

Early life

Mercury was born on the island of Zanzibar. His parents, Bomi and Jer Bulsara,[a] were Parsis from the Gujarat region of the then province of Bombay Presidency in British India.[13][b] The family surname is derived from the town of Bulsar (also known as Valsad) in southern Gujarat. As Parsis, Freddie and his family practised the Zoroastrian religion. The Bulsara family had moved to Zanzibar in order for his father to continue his job as a cashier at the British Colonial Office. He had one younger sister, Kashmira.[14]

In 1954, at the age of eight, Mercury was sent to study at St. Peter's School,[15] a boarding school for boys in Panchgani near Bombay (now Mumbai), India.[16] At school, he formed a popular school band, The Hectics, for which he played piano. A friend from the time recalls that he had "an uncanny ability to listen to the radio and replay what he heard on piano".[17] It was also at St. Peter's where he began to call himself "Freddie". Mercury remained in India for most of his childhood, living with his grandmother and aunt. He completed his education in India at St. Mary's School, Bombay.[18]

At the age of 17, Mercury and his family fled from Zanzibar for safety reasons due to the 1964 Zanzibar Revolution.[8] The family moved into a small house in Feltham, Middlesex, England. Mercury enrolled at Isleworth Polytechnic (now West Thames College) in West London where he studied art. He ultimately earned a Diploma in Art and Graphic Design at Ealing Art College, later using these skills to design the Queen crest. Mercury remained a British citizen for the rest of his life.

Following graduation, Mercury joined a series of bands and sold second-hand clothes in the Kensington Market in London. He also held a job at Heathrow Airport. Friends from the time remember him as a quiet and shy young man who showed a great deal of interest in music.[19] In 1969 he formed the band Ibex, later renamed Wreckage. When this band failed to take off, he joined a second band called Sour Milk Sea. However, by early 1970 this group broke up as well.[20]

In April 1970, Mercury joined with guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor who had previously been in a band called Smile. Despite reservations from the other members, Mercury chose the name "Queen" for the new band. He later said about the band's name, "I was certainly aware of the gay connotations, but that was just one facet of it".[1] At about the same time, he changed his surname, Bulsara, to Mercury.

Influences

As a child, Mercury listened to a considerable amount of Indian music, and one of his early influences was the Bollywood playback singer Lata Mangeshkar, whom he saw live in India.[21] After moving to England, Mercury became a fan of Aretha Franklin, The Who, Jim Croce, Elvis Presley, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon and The Beatles.[22] Another one of Mercury's favourite performers was singer and actress Liza Minnelli. He once explained: "One of my early inspirations came from Cabaret. I absolutely adore Liza Minnelli. The way she delivers her songs — the sheer energy."[23]

Career

Singer

Although Mercury's speaking voice naturally fell in the baritone range, he delivered most songs in the tenor range.[24] Biographer David Bret described his voice as "escalating within a few bars from a deep, throaty rock-growl to tender, vibrant tenor, then on to a high-pitched, perfect coloratura, pure and crystalline in the upper reaches".[25] Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé, with whom Mercury recorded an album, expressed her opinion that "the difference between Freddie and almost all the other rock stars was that he was selling the voice".[26] As Queen's career progressed, he would increasingly alter the highest notes of their songs when live, often harmonising with seconds, thirds or fifths instead. Mercury suffered from vocal fold nodules and claimed never to have had any formal vocal training.[27]

Songwriter

Mercury wrote 10 of the 17 songs on Queen's Greatest Hits album: "Bohemian Rhapsody", "Seven Seas of Rhye", "Killer Queen", "Somebody to Love", "Good Old-Fashioned Lover Boy", "We Are the Champions", "Bicycle Race", "Don't Stop Me Now", "Crazy Little Thing Called Love" and "Play the Game".

The most notable aspect of his songwriting involved the wide range of genres that he used, which included, among other styles, rockabilly, progressive rock, heavy metal, gospel and disco. As he explained in a 1986 interview, "I hate doing the same thing again and again and again. I like to see what's happening now in music, film and theatre and incorporate all of those things."[28] Compared to many popular songwriters, Mercury also tended to write musically complex material. For example, "Bohemian Rhapsody" is acyclic in structure and comprises dozens of chords.[29][30] He also wrote six songs from Queen II which deal with multiple key changes and complex material. "Crazy Little Thing Called Love", on the other hand, contains only a few chords. Despite the fact that Mercury often wrote very intricate harmonies, he also claimed that he could barely read music.[31] He wrote most of his songs on the piano and used a wide variety of different key signatures.[29]

Live performer

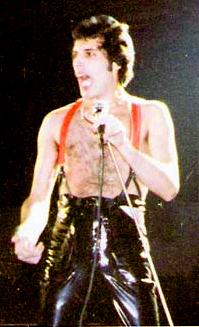

Mercury was noted for his live performances, which were often delivered to stadium audiences around the world. He displayed a highly theatrical style that often evoked a great deal of participation from the crowd. A writer for The Spectator described him as "a performer out to tease, shock and ultimately charm his audience with various extravagant versions of himself".[32] David Bowie, who performed at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert and recorded the song "Under Pressure" with Queen, praised Mercury's performance style, saying: "Of all the more theatrical rock performers, Freddie took it further than the rest... he took it over the edge. And of course, I always admired a man who wears tights. I only saw him in concert once and as they say, he was definitely a man who could hold an audience in the palm of his hand."[33]

One of Mercury's most notable performances with Queen took place at Live Aid in 1985, during which the entire stadium audience of 72,000 people clapped, sang and swayed in unison. Queen's performance at the event has since been voted by a group of music executives as the greatest live performance in the history of rock music. The results were aired on a television program called "The World's Greatest Gigs".[34][35] In reviewing Live Aid in 2005, one critic wrote, "Those who compile lists of Great Rock Frontmen and award the top spots to Mick Jagger, Robert Plant, etc all are guilty of a terrible oversight. Freddie, as evidenced by his Dionysian Live Aid performance, was easily the most godlike of them all."[36]

Over the course of his career, Mercury performed an estimated 700 concerts in countries around the world with Queen. A notable aspect of Queen concerts was the large scale involved.[28] He once explained, "We're the Cecil B. DeMille of rock and roll, always wanting to do things bigger and better."[28] The band were the first ever to play in South American stadiums, breaking worldwide records for concert attendance in the Morumbi Stadium in São Paulo in 1981.[37] In 1986, Queen also played behind the Iron Curtain, when they performed to a crowd of 80,000 in Budapest.[38] Mercury's final live performance with Queen took place on 9 August 1986 at Knebworth Park in England and drew an attendance estimated as high as 300,000.[39]

Instrumentalist

As a young boy in India, Mercury received formal piano training up to the age of nine. Later on, while living in London, he learned guitar. Much of the music he liked was guitar-oriented: his favourite artists at the time were The Who, the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie and Led Zeppelin. He was often self-deprecating about his own skills on both instruments and from the early 1980s onwards began extensively using guest keyboardists for both Queen and his solo career. Most notably, he enlisted Fred Mandel (an American musician who also worked for Pink Floyd, Elton John and Supertramp) for his first solo project, and from 1985 onwards collaborated extensively with Mike Moran, leaving most of the keyboard work exclusively to him.

Mercury played the piano in many of Queen's most popular songs, including "Killer Queen", "Bohemian Rhapsody", "Good Old Fashioned Lover Boy", "We Are the Champions", "Somebody To Love" and "Don't Stop Me Now". He used concert grand pianos and, occasionally, other keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord. From 1980 onwards, he also made extensive use of synthesisers in the studio. Queen guitarist Brian May claims that Mercury was unimpressed with his own abilities at the piano and used the instrument less over time because he wanted to walk around onstage and entertain the audience.[40] Although he wrote many lines for guitar, Mercury possessed only rudimentary skills on the instrument. Songs like "Ogre Battle" and "Crazy Little Thing Called Love" were composed on guitar; the latter featured Mercury playing acoustic guitar both on stage and in the studio.

Solo career

In addition to his work with Queen, Mercury put out two solo albums and several singles. Although his solo work was not as commercially successful as most Queen albums, the two off-Queen albums and several of the singles debuted in the top 10 of the UK Album Charts. His first solo effort involved his contribution to the Richard "Wolfie" Wolf mix of Love Kills on the 1984 album (the song also used as the end title theme for National Lampoon's "Loaded Weapon") and new soundtrack to the 1926 Fritz Lang film Metropolis. The song, produced by Giorgio Moroder, debuted at the number 10 position in the UK charts.[41]

Mercury's two full albums outside the band were Mr. Bad Guy (1985) and Barcelona (1988). The former is a pop-oriented album that emphasises disco and dance music. "Barcelona" was recorded and performed with the opera singer Montserrat Caballé, whom he had long admired. Mr. Bad Guy debuted in the top ten of the UK Album Charts.[41] In 1993, a remix of "Living on My Own", a single from the album, reached the #1 position on the UK Singles Charts.[42] The song also garnered Mercury a posthumous Ivor Novello Award. Allmusic critic Eduardo Rivadavia describes Mr. Bad Guy as "outstanding from start to finish" and expressed his view that Mercury "did a commendable job of stretching into uncharted territory".[43] In particular, the album is heavily synthesiser-driven in a way that is not characteristic of previous Queen albums.

Barcelona, recorded with Spanish soprano Montserrat Caballé, combines elements of popular music and opera. Many critics were uncertain what to make of the album; one referred to it as "the most bizarre CD of the year".[44] Caballé, on the other hand, considered the album to have been one of the great successes of her career [citation needed]. The title song from the album debuted at the #8 position in the UK charts and was a hit in Spain,[45] where the song received massive air play as the official hymn of the 1992 Summer Olympics (held in Barcelona one year after Mercury's death). Ms. Caballé sang it live at the opening of the Olympics with Mercury's part played on a screen.

In addition to the two solo albums, Mercury released several singles, including his own version of the hit The Great Pretender by The Platters, which debuted at number five in the UK in 1987.[41] In September 2006, a compilation album featuring Mercury's solo work was released in the UK in honour of what would have been his 60th birthday. The album debuted in the top 10 of the UK Album Charts.[46]

In 1981–1983, Mercury recorded several tracks with Michael Jackson, including a demo of "State of Shock", "Victory" and "There Must Be More to Life Than This"; none of these collaborations were officially released, although bootleg recordings exist. Jackson went on to record the former song with Mick Jagger for The Jacksons, and Mercury included the solo version of the latter song on his Mr. Bad Guy album.

Personal life

In the early 1970s Mercury had a long-term relationship with Mary Austin, whom he had met through guitarist Brian May. He lived with Austin for several years in West Kensington. By the mid-1970s, however, the singer had begun an affair with a male American record executive at Elektra Records, which ultimately resulted in the end of his relationship with Austin.[47] Mercury and Austin nevertheless remained close friends through the years, with Mercury often referring to her as his only true friend. In a 1985 interview, Mercury said of Austin, "All my lovers asked me why they couldn't replace Mary [Austin], but it's simply impossible. The only friend I've got is Mary and I don't want anybody else. To me, she was my common-law wife. To me, it was a marriage. We believe in each other, that's enough for me."[48] He also wrote several songs about Austin, the most notable of which is "Love of My Life". Mercury was also the godfather of Mary's oldest son, Richard.[40]

By 1979, Mercury began to frequently visit gay bathhouses and clubs where he met many short-term partners.[49] By 1985, he began another long-term relationship with a hairdresser named Jim Hutton. Hutton, who himself was tested HIV-positive in 1990,[50] lived with Mercury for the last six years of his life, nursed him during his illness and was present at his bedside when he died. Hutton also claims that Mercury died wearing a wedding band that Hutton had given him.[50] Hutton passed away 1 January 2010 due to complications of a smoking-related illness.[51]

Although he cultivated a flamboyant stage personality, Mercury was a very shy and retiring man in person, particularly around people he didn't know well.[14][17][26] He also granted very few interviews. Mercury once said of himself: "When I'm performing I'm an extrovert, yet inside I'm a completely different man."[52]

Illness and death

According to his partner Jim Hutton, Mercury was diagnosed with AIDS shortly after Easter of 1987.[53] Around that time, Mercury claimed in an interview to have tested negative for the virus.[26] Despite the denials, the British press pursued the rampant rumours over the next few years, fuelled by Mercury's increasingly gaunt appearance, Queen's absence from touring, and reports from former lovers to various tabloid journals.[54] Toward the end of his life, he was routinely stalked by photographers, while the daily tabloid newspaper The Sun featured a series of articles claiming that he was seriously ill. However, Mercury and his colleagues and friends continually denied the stories, even after one front page article published on 29 April 1991, which showed Mercury appearing very haggard in what was now a rare public appearance.[55]

On 22 November 1991, Mercury called Queen's manager Jim Beach over to his Kensington home, to discuss a public statement. The next day, 23 November, the following announcement was made to the press on behalf of Mercury:[56]

Following the enormous conjecture in the press over the last two weeks, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV positive and have AIDS. I felt it correct to keep this information private to date to protect the privacy of those around me. However, the time has come now for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth and I hope that everyone will join with me, my doctors, and all those worldwide in the fight against this terrible disease. My privacy has always been very special to me and I am famous for my lack of interviews. Please understand this policy will continue.

A little over 24 hours after issuing that statement, Mercury died on the evening of 24 November 1991 at the age of 45. The official cause of death was bronchial pneumonia resulting from AIDS.[57] The news of his death had reached newspaper and television crews by the early hours of 25 November.[58]

Although he had not attended religious services in years, Mercury's funeral was conducted by a Zoroastrian priest. Elton John, David Bowie and the remaining members of Queen attended the funeral. He was cremated at Kensal Green Cemetery and his ashes scattered in an undisclosed location.

In his will, Mercury left the vast majority of his wealth, including his home and recording royalties, to Mary Austin, and the remainder to his parents and sister. He further left £500,000 to his chef Joe Fanelli, £500,000 to his personal assistant Peter Freestone, £100,000 to his driver Terry Giddings, and £500,000 to Jim Hutton.[59] Mary Austin continues to live at Mercury's home, Garden Lodge, Kensington, with her family.[59] Hutton was involved in a 2000 biography of Mercury, Freddie Mercury, the Untold Story, and also gave an interview for The Times for what would have been Mercury's 60th birthday.[53] He moved back to the Republic of Ireland in 1995, and died there on 1 January 2010.

Criticism and controversy

HIV status and sexual orientation

Mercury hid his HIV status from the public for several years, and it has been suggested that he could have raised a great deal of money and awareness earlier by speaking truthfully about his situation and his fight against the disease.[33][60] While some critics have also suggested that Mercury hid his sexual orientation from the public,[8][26][61] other sources refer to the singer as having been "openly gay".[9][62] Mercury referred to himself as "gay" in a 1974 interview with NME magazine.[63] He also referred to himself as "bisexual" on occasion.[64][65] On the other hand, he would often distance himself from his partner, Jim Hutton, during public events in the 1980s.[50] A writer for a gay online newspaper felt that audiences may have been overly naive about the matter: "While in many respects he was overtly queer his whole career ("I am as gay as a daffodil, my dear" being one of his most famous quotes), his sexual orientation seemed to pass over the heads of scrutinising audiences and pundits (both gay and straight) for decades".[66] John Marshall of Gay Times expressed the following opinion in 1992: "[Mercury] was a 'scene-queen', not afraid to publicly express his gayness but unwilling to analyse or justify his 'lifestyle' ... It was as if Freddie Mercury was saying to the world, "I am what I am. So what?" And that in itself for some was a statement."[66]

Other controversies

Members of Queen were widely criticised in the 1980s for the fact that they broke a United Nations cultural boycott by performing a series of shows at Sun City in 1984, an entertainment complex in Bophuthatswana, a homeland of (then) apartheid South Africa. As a result of these shows, Queen was placed on a United Nations list of artists who broke the boycott and was widely criticised in magazines such as the NME.[36]

A further controversy ensued in August 2006, when an organisation calling itself the Islamic Mobilization and Propagation petitioned the Zanzibar government's culture ministry, demanding that a large-scale celebration of what would have been Mercury's sixtieth birthday be cancelled. The organisation issued several complaints about the planned celebrations, including that Mercury was not a true Zanzibari and that he was gay, which is not in accordance with their interpretation of sharia. The organisation claimed that "associating Mercury with Zanzibar degrades our island as a place of Islam".[62] The planned celebration was cancelled.

Legacy

Continued popularity

The extent to which Mercury's death may have enhanced Queen's popularity is not clear, but sales of Queen albums went up dramatically in 1992, the year following his death.[67] In 1992 one American critic noted, "what cynics call the 'dead star' factor had come into play — Queen is in the middle of a major resurgence".[68] The movie Wayne's World, which featured "Bohemian Rhapsody", also came out in 1992. According to the Recording Industry Association of America, Queen have sold 32.5 million albums in the United States, about half of which have been sold since Mercury's death in 1991.[69]

Estimates of Queen's total worldwide record sales to date have been set as high as 300 million.[70] In the UK, Queen have now spent more collective weeks on the UK Album Charts than any other musical act (including The Beatles),[71] and Queen's Greatest Hits is the highest selling album of all time in the UK.[72] Two of Mercury's songs, "We Are the Champions" and "Bohemian Rhapsody", have also each been voted as the greatest song of all time in major polls by Sony Ericsson[73] and Guinness World Records,[74] respectively. The former poll was an attempt to determine the world's favourite song, while the Guinness poll took place in the UK. In October 2007, the video for "Bohemian Rhapsody" was voted the greatest of all time by readers of Q magazine.[75] Consistently rated as one of the greatest singers in the history of popular music, Mercury was voted second to Mariah Carey in MTV's 22 Greatest Voices in Music.[9] Additionally, in January 2009, Mercury was voted second to Robert Plant in a poll of the greatest voices in rock, on the digital radio station Planet Rock.[76] In May 2009, Classic Rock magazine voted Freddie Mercury as the greatest singer in rock.[11]

Tributes

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

A statue in Montreux, Switzerland (by sculptor Irena Sedlecka) has been erected as a tribute to Mercury. It stands 3 metres high overlooking Lake Geneva and was unveiled on 25 November 1996 by Freddie's father and Montserrat Caballé. Beginning in 2003, fans from around the world gather in Switzerland annually to pay tribute to the singer as part of the "Freddie Mercury Montreux Memorial Day" on the first weekend of September and the Bearpark And Esh Colliery Band played at the Freddie Mercury statue on the 1st of June 2010.[77] A Royal Mail stamp was issued in honour of Mercury as part of the Millennium Stamp series. A plaque was also erected at the site of the family home in Feltham where Mercury and his family moved upon arriving in England in 1964.

A tribute to Queen has been on display at the Fremont Street Experience in downtown Las Vegas throughout 2009 on its video canopy. In December 2009 a large model of Mercury wearing tartan was put on display in the centre of Edinburgh as publicity for the run of We Will Rock You at the Playhouse Theatre.

In late 2009 a plaque was installed in Feltham High Street in memory of his achievements.

A statue of Mercury stands over the entrance to the Dominion Theatre in London where the main show, from May 2002, has been Ben Elton's We Will Rock You.

Importance in AIDS history

Freddie Mercury's death represented an important event in the history of AIDS.[78] In April 1992, the remaining members of Queen founded The Mercury Phoenix Trust and organised The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert for AIDS Awareness, which took place Easter Monday, 20 April 1992.[79] The Mercury Phoenix Trust has since raised millions of pounds for various AIDS charities. The tribute concert, which took place at Wembley Stadium for an audience of 72,000, featured a wide variety of guests including Robert Plant, Roger Daltrey, Extreme, Elton John, Metallica, David Bowie, Annie Lennox, Tony Iommi, Guns N' Roses, Elizabeth Taylor, George Michael, Def Leppard and Liza Minnelli. The concert was broadcast live to 76 countries and had an estimated viewing audience of 1 billion people.[80]

Appearances in lists of influential individuals

Several popularity polls conducted over the past decade indicate that Freddie Mercury's reputation may in fact have been enhanced since his death. For instance, in 2002 he was ranked number 58 in the list of the 100 Greatest Britons, sponsored by the BBC and voted for by the public.[81] He was further listed at the 52nd spot in a 2007 Japanese national survey of the 100 most "influential heroes".[82] Despite the fact that he had been criticised by gay activists for hiding his HIV status, author Paul Russell included Mercury in his book "The Gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present."[83] Other entertainers on Russell's list included Liberace and Rock Hudson. In 2006, Time Asia magazine named him as one of the most influential Asian heroes of the past 60 years: The article credited Mercury with having "duplicated in popular music what other Indians — such as Salman Rushdie and Vikram Seth — have done in literature: taking the coloniser's art form and representing it in a manner richer and more dazzling than many Anglophones thought possible."[9] In 2008, Rolling Stone' magazine ranked Mercury #18 in its list of the "Top 100 Singers Of All Time".[6]

Discography

Notes

| a) ^ | On Mercury's birth certificate,[13] his parents defined themselves with "Nationality: British Indian" and "Race: Parsi". The Parsis are an originally Persian ethnic group of the Indian subcontinent who follow Zoroastrianism. |

| b) ^ | The Bulsara family gets its name from Bulsar, a city and district that is now in the Indian state of Gujarat and is today officially known as Valsad. In the 17th century, Bulsar was one of the five centres of the Zoroastrian religion (the other four were also in what is today Gujarat) and consequently "Bulsara" is a relatively common name amongst Zoroastrians. |

| c) ^ | Mercury is also portrayed as himself in the animated show Cromartie High School as the character Freddie, and in the British Channel 4 show House Of Rock along with Marc Bolan, John Lennon, Notorious BIG, John Denver and Kurt Cobain. |

References

- ^ a b Highleyman 2005.

- ^ http://mr-mercury.co.uk/Images/Birthcertificatefreddie.jpg

- ^ Allen, Jeffrey (9 January 1994), Jeffrey Allen's Secrets of singing – Google Books, Books.google.com, ISBN 9780769278056, retrieved 22 November 2009

- ^ [1]

- ^ Dance: Deux the fandango.

- ^ a b c RollingStone.com – 100 Greatest Singers of All Time.

- ^ The Great British Battle of the Bands.

- ^ a b c Januszczak 1996.

- ^ a b c d Fitzpatrick 2006.

- ^ list of Blender and MTV2's "22 Greatest Voices" (archived at www.amiannoying.com).

- ^ a b Classic Rock, "50 Greatest Singers in Rock", May 2009

- ^ Allmusic: Queen biography

- ^ a b "Linda B" 2000.

- ^ a b Das 2000. Cite error: The named reference "Das_2000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Freddie Mercury India School Tour

- ^ Freddie Mercury Biography.

- ^ a b O'Donnell 2005.

- ^ "Tribute to King of "Queen" Freddie Mercury | NowPublic News Coverage". Nowpublic.com. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ Davis 1996, pp. 1, 10.

- ^ Skala 2006.

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 7.

- ^ Davis 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Rush 1977a.

- ^ Freestone, Peter (2001), Freddie Mercury: an intimate memoir ... – Google Books, Books.google.com, ISBN 9780711986749, retrieved 22 November 2009

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 26.

- ^ a b c d Cain 2006.

- ^ Rush 1977b.

- ^ a b c Wenner 2001.

- ^ a b Queen 1992.

- ^ Aledort 2003.

- ^ Coleman 1981.

- ^ Blaikie 1996.

- ^ a b Ressner 1992 Cite error: The named reference "Ressner_1992" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Minchin 2005.

- ^ BBC News 2005b.

- ^ a b Harris 2005.

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 91.

- ^ Pye 1986.

- ^ Jones 1999.

- ^ a b Longfellow 2006

- ^ a b c Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 809.

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 811.

- ^ Rivadavia & <not dated>.

- ^ Bradley 1992.

- ^ Rees & Crampton 1999, p. 810.

- ^ ukmusic.com 2006

- ^ Teckman 2004, part 2.

- ^ Hauptfuhrer 1977.

- ^ Teckman 2004, part 3.

- ^ a b c Hutton 1994.

- ^ http://www.brianmay.com/brian/brianssb/brianssb.html

- ^ Myers 1991.

- ^ a b Teeman 2006

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 138

- ^ [2]

- ^ Bret 1996, p. 179.

- ^ Biography Channel 2007.

- ^ [3]

- ^ a b Wigg 2000.

- ^ Sky 1992, p. 163

- ^ Landesman 2006

- ^ a b BBC News 2006

- ^ Webb 1974

- ^ FREDDIE MERCURY & QUEEN: PAST, PRESENT & FUTURE IMPRESSIONS. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Freddie Mercury bisexual

- ^ a b Urban & <not dated> Cite error: The named reference "Urban_notdated" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ RIAA 2007.

- ^ Brown 1992.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum – 22 November 2009". RIAA. Retrieved 22 November 2009.

- ^ Cota 2006

- ^ BBC 2005a.

- ^ Brown 2006.

- ^ Haines 2005

- ^ CNN 2002

- ^ BBC News 2007.

- ^ The Top 40 Greatest Voices in Rock The Sun

- ^ Bishton 2004.

- ^ National AIDS Trust 2006

- ^ Stothard 1992

- ^ ABC Television 2007

- ^ BBC – 100 great British heroes

- ^ "James" 2007

- ^ Russell 2002

^ Notation done in Scientific Pitch, and thus is written one octave lower than what is displayed here.

Bibliography

- ABC Television (20 August 2007), Freddie Mercury: The Tribute Concert, Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Aledort, And (29 November 2003), Guitar Tacet for Queen's Bohemian Rhapsody.

- "Linda B" (2000), Certificate of Birth, Chorley: mr-mercury.co.uk.

- Barnes, Ken (20 June 1974), "Album Review: Queen II" ([dead link]), Rolling Stone Magazine.

- BBC News (18 April 2001), Sinatra is voice of the century ([dead link]), London: bbc.co.uk.

- BBC News (22 August 2002), BBC reveals 100 great British heroes, London: bbc.co.uk, retrieved 4 January 2010.

- BBC News (4 July 2005), Queen top UK album charts league, London: bbc.co.uk, retrieved 4 January 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - BBC News (9 November 2005), Queen win greatest live gig poll, London: bbc.co.uk, retrieved 4 January 2010

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link). - BBC News (1 September 2006), Zanzibar angry over Mercury bash, London: bbc.co.uk, retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Biography Channel (2007), Freddie Mercury, London: thebiographychannel.co.uk.

- Boyce, Simon (1995), Freddie Mercury, Bristol: Parragon, ISBN 1861050542.

- BBC News (8 October 2007), Queen's rhapsody voted best video, BBC News Online, retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Middleton, Christopher (31 August 2004), Bishton, Derek (ed.), Freddie's rhapsody, London: telegraph.co.uk, retrieved 2 May 2010.

- Blaikie, Thomas (7 December 1996), "Camping at High Altitude", The Spectator.

- Bradley, J. (20 July 1992), "Mercury soars in opera CD: Bizarre album may be cult classic", The Denver Post, Denver: MNG.

- Bret, David (1996), Living On the Edge: The Freddie Mercury Story, London: Robson Books, ISBN 1861052561.

- Brown, G. (19 April 1992), "Queen's popularity takes ironic turn", The Denver Post, Denver: MNG.

- Brown, Mark (16 November 2006), "Queen are the champions in all-time album sales chart", The Guardian, London: Guardian News and Media.

- Cain, Matthew, dir. (2006), Freddie Mercury: A Kind of Magic, London: British Film Institute

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link).. - Clarke, Ross (1991), Freddie Mercury: A Kind of Magic, Oxted: Kingsfleet Publications, ISBN 1874130019.

- CNN (9 May 2002), Queen in Rhapsody over hit award, Atlanta: cnn.com

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help). - Cohen, Scott (April 1975), "Queen's Freddie Mercury Shopping for an Image in London", Circus Magazine, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Coleman, Ray, ed. (2 May 1981), "The Man Who Would Be Queen", Melody Maker, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Cota, Erich Adolfo Moncada (25 January 2006), "Queen Proves There's Life After Freddie", Ohmynews.com, Seoul.

- D'Esti Miller, Sarah (19 July 2007), "EPAC's 'Rhapsody' Hits Too Many Wrong Notes", Press & Sun-Bulletin, Binghamton, NY, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Das, Lina (2006), "The Great Pretender", The Mail on Sunday, London (published 26 November 2000), retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Davis, Andy (1996), "Queen Before Queen", Record Collector Magazine, vol. 3, no. 199.

- Evans, David; Minns, David (1992), Freddie Mercury: This is the Real Life, London: Britannia, ISBN 0951993739.

- Fitzpatrick, Liam (13 November 2006), "Farookh Bulsara", Time Magazine, Asia Edition, 60 Years of Asian Heroes, vol. 168, no. 21, Hong Kong: Time Asia.

- Freestone, Peter (1998), Mister Mercury, London: Tusitala, ISBN 0953334104.

- Freestone, Peter (1999), Freddie Mercury: An Intimate Memoir By the Man Who Knew Him Best, London: Omnibus Press, ISBN 0711986746.

- Guazzelli, Andrés E. (8 February 2007), The Voice: Freddy Mercury > Characteristics of his voice ([dead link]), Buenos Aires: f-mercury.com.ar.

- Gunn, Jacky; Jenkins, Jim (1992), Queen: As It Began, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, ISBN 0330332597.

- Haines, Lester (29 September 2005), "We Are the Champions" voted world's fave song, London: www.theregister.co.uk.

- Harris, John (14 January 2005), "The Sins of St. Freddie", Guardian on Friday, London: Guardian News and Media.

- Hauptfuhrer, Fred (5 December 1977), "For A Song: The Mercury that's rising in rock is Freddie the satiny seductor of Queen", People Magazine, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Highleyman, Liz (9 September 2005), "Who was Freddie Mercury?", Seattle Gay News, vol. 33, no. 36.

- Hutton, Jim; Waspshott, Tim (1994), Mercury and Me, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0747519226.

- Hutton, Jim (22 October 1994), "Freddie and Jim" A Love Story", The Guardian, "Weekend magazine".

- Hyder, Rehan (2004), Brimful of Asia: Negotiating Ethnicity on the UK Music Scene, Ashgate, ISBN 9780754640646, ISBN 0754640647.

- Jackson, Laura (1997), Mercury: The King of Queen, London: Smith Gryphon, ISBN 185685132X.

- "James" (1 April 2007), NTV program review: History's 100 Most Influential People: Hero Edition, Saitama: japanprobe.com.

- Januszczak, Waldemar (17 November 1996), "Star of India", The Sunday Times, London.

- Jones, Lesley-Ann (1998), Freddie Mercury: The Definitive Biography, London: Coronet, ISBN 9780340672099, ISBN 0340672099.

- Jones, Tim (July 1999), "How Great Thou Art, King Freddie", Record Collector.

- Landesman, Cosmo (10 September 2006), "Freddie, a Very Private Rock Star", The Sunday Times, London, retrieved 2 May 2010

{{citation}}: More than one of|work=and|periodical=specified (help). - Longfellow, Matthew, dir. (21 March 2006), Classic Albums: Queen: The Making of "A Night at the Opera", Aldershot: Eagle Rock Entertainment

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Hudson, Jeffrey (1995), Freddie Mercury & Queen, Chessington, Surrey: Castle Communications, ISBN 1860740405.

- Mehar, Rakesh (18 September 2006), "God Should've Saved the Queen", The Hindu (Kochi), New Delhi: hinduonline.com.

- Mercury, Freddie; Brooks, Greg; Lupton, Simon (2006), Freddie Mercury: A life, In His Own Words, London: Mercury Songs, ISBN 0955375800.

- Minchin, Ryan, dir. (2005), The World's Greatest Gigs, London: Initial Film & Television

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link). - Myers, Paul (25 November 1991), "Queen star dies after Aids statement", The Guardian, London, retrieved 2 May 2010.

- National AIDS Trust (2006), 25 years of HIV – a UK perspective, London: National AIDS Trust press office, archived from the original on 22 December 2006.

- O'Donnell, Lisa (7 July 2005), "Freddie Mercury, WSSU professor were boyhood friends in India, Zanzibar", RelishNow!, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Queen (1992), "Bohemian Rhapsody", Queen: Greatest Hits: Off the Record, Eastbourne/Hastings: Barnes Music Engraving, ISBN 0863599508.

- Prato, Greg (<not dated>), Freddie Mercury, Ann Arbor: allmusic.com

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link). - Zimmermann, M (2004), Pye, Ian (ed.), "Hungarian Rhapsody" ([dead link] – Scholar search), Neuropeptides, 38 (6), London: IPC Media (published 9 August 1986): 375–6, ISSN 0143-4179, PMID 15651128

{{citation}}: External link in|format=|periodical=and|journal=specified (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help). - Rees, Dafydd; Crampton, Luke (1999), Summers, David (ed.), The Rock Stars Encyclopedia, London: Dorling Kindersley.

- Ressner, Jeffry (9 January 1992), "Queen singer is rock's first major AIDS casualty", Rolling Stone Magazine, vol. 621.

- RIAA (2007), Gold and Platinum Record Database, Washington: Recording Industry Association of America.

- Rivadavia, Eduardo (<not dated>), Mr. Bad Guy (Overview), Ann Arbor: Allmusic

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link). - Rush, Don (1977a), "Queen's Freddie Mercury", Circus Magazine (published 17 March 1977).

- Rush, Don (1977b), "title unknown", Circus Magazine (published 5 December 1977), archived from the original on 20 October 2007, retrieved 24 September 2009.

- Russell, Paul (2002), The Gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present, Seacaucus: Kensington/Citadel, ISBN 0758201001.

- Skala, Martin (2006), Concertography > Freddie Mercury live > Early days, Plzen, Czech Republic: queenconcerts.com.

- Sky, Rick (1992), The Show Must Go On, London: Fontana, ISBN 9780006378433.

- Stothard, Peter, ed. (26 April 1992), "Freddie Tribute" ([dead link] – Scholar search), The Times, London: Times Newspapers

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - Taraporevala, Sooni (2004), Parsis: The Zoroastrians of India: A Photographic Journey (2nd ed.), Woodstock/New York: Overlook Press, ISBN 1585675938.

- Teckman, Kate, dir. (2004), Freddie's Loves, London: North One Television

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) *part 2* *part 3*. - Teeman, Tim (7 September 2006), "I Couldn't Bear to See Freddie Wasting Away", TheTimes, London, retrieved 2 May 2010

{{citation}}: More than one of|work=and|periodical=specified (help). - UKMusic.com (10 September 2006), UK Top 40 Albums Chart 10 September 2006.

- Urban, Robert (<not dated>), Freddie Mercury & Queen: Past, Present & Future Impressions, afterelton.com

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link). - Webb, Julie (4 April 1974), "Queen" ([dead link] – Scholar search), NME, London: IPC Media

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - WENN (9 April 2005), "Legend Freddie Mercury Honoured", Femalefirst.co.uk, Wigan, Lancs.

- Wenner, Jann; et al. (2001), "Queen", Hall of Fame Inductees, Cleveland: Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help). - Wigg, David (22 January 2000), "Mercury Left Me His Millions", Daily Mail Weekend.

Further reading

- Template:MySpace (official EMI Music)

- Freddie Mercury discography at Discogs

- Freddie Mercury at AllMusic

- Freddy Mercury at Last.FM

- Freddie Mercury at IMDb

- Freddie Mercury at Find a Grave

- 1946 births

- 1991 deaths

- 1970s singers

- 1980s singers

- 1990s singers

- AIDS-related deaths in England

- Bisexual musicians

- BRIT Award winners

- British people of Parsi descent

- English male singers

- English musicians

- English people of Indian descent

- English pianists

- English rock guitarists

- English rock keyboardists

- English rock musicians

- English rock singers

- English singer-songwriters

- English singers

- English songwriters

- English tenors

- English Zoroastrians

- Freddie Mercury

- Ivor Novello Award winners

- LGBT musicians from the United Kingdom

- LGBT people from Africa

- LGBT people from South Asia

- Parsi people

- Queen (band) members

- Zanzibari Indians