Grus (constellation)

| Constellation | |

| |

| Abbreviation | Gru |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Gruis |

| Pronunciation | /ˈɡrʌs/, or colloquially /ˈɡruːs/; genitive /ˈɡruːɪs/ |

| Symbolism | the crane |

| Right ascension | 21h 27.4m to 23h 27.1m [1] |

| Declination | −36.31° to −56.39°[1] |

| Quadrant | SQ4 |

| Area | 366 sq. deg. (45th) |

| Main stars | 8 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 28 |

| Stars with planets | 6 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 3 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 1 |

| Brightest star | α Gru (Alnair) (1.73m) |

| Messier objects | 0 |

| Meteor showers | 0 |

| Bordering constellations | Piscis Austrinus Microscopium Indus Tucana Phoenix Sculptor |

| Visible at latitudes between +34° and −90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of October. | |

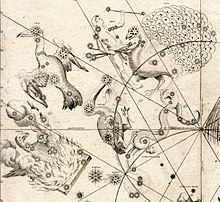

Grus (/ˈɡrʌs/, or colloquially /ˈɡruːs/) is a constellation in the southern sky. Its name is Latin for the crane, a type of bird. It is one of twelve constellations conceived by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Grus first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter (14-inch) celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and was depicted in Johann Bayer's star atlas Uranometria of 1603. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille gave Bayer designations to its stars in 1756, some of which had been previously considered part of the neighbouring constellation Piscis Austrinus. The constellations Grus, Pavo, Phoenix and Tucana are collectively known as the "Southern Birds".

The constellation's brightest star, Alpha Gruis, is also known as Alnair and appears as a 1.7-magnitude blue-white star. Beta Gruis is a red giant variable star with a minimum magnitude of 2.3 and a maximum magnitude of 2.0. Six star systems have been found to have planets: the red dwarf Gliese 832 is one of the closest stars to Earth to have a planetary system. Another—WASP-95—has a planet that orbits every two days. Deep-sky objects found in Grus include the planetary nebula IC 5148, also known as the Spare Tyre Nebula, and a group of four interacting galaxies known as the Grus Quartet.

History[edit]

The stars that form Grus were originally considered part of the neighbouring constellation Piscis Austrinus (the southern fish), with Gamma Gruis seen as part of the fish's tail.[2] The stars were first defined as a separate constellation by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius, who created twelve new constellations based on the observations of the southern sky by the Dutch explorers Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman, who had sailed on the first Dutch trading expedition, known as the Eerste Schipvaart, to the East Indies. Grus first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius with Jodocus Hondius. Its first depiction in a celestial atlas was in the German cartographer Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603.[3] De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue the same year under the Dutch name Den Reygher, "The Heron",[4] but Bayer followed Plancius and Hondius in using Grus.[2]

An alternative name for the constellation, Phoenicopterus (Latin "flamingo"), was used briefly during the early 17th century, seen in the 1605 work Cosmographiae Generalis by Paul Merula of Leiden University and a c. 1625 globe by Dutch globe maker Pieter van den Keere. Astronomer Ian Ridpath has reported the symbolism likely came from Plancius originally, who had worked with both of these people.[2] Grus and the nearby constellations Phoenix, Tucana and Pavo are collectively called the "Southern Birds".[5]

The stars that correspond to Grus were generally too far south to be seen from China. In Chinese astronomy, Gamma and Lambda Gruis may have been included in the tub-shaped asterism Bàijiù, along with stars from Piscis Austrinus.[2] In Central Australia, the Arrernte and Luritja people living on a mission in Hermannsburg viewed the sky as divided between them, east of the Milky Way representing Arrernte camps and west denoting Luritja camps. Alpha and Beta Gruis, along with Fomalhaut, Alpha Pavonis and the stars of Musca, were all claimed by the Arrernte.[6]

Characteristics[edit]

Grus is bordered by Piscis Austrinus to the north, Sculptor to the northeast, Phoenix to the east, Tucana to the south, Indus to the southwest, and Microscopium to the west. Bayer straightened the tail of Piscis Austrinus to make way for Grus in his Uranometria.[2] Covering 366 square degrees, it ranks 45th of the 88 modern constellations in size and covers 0.887% of the night sky.[7] The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "Gru".[8] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined as a polygon of 6 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 21h 27.4m and 23h 27.1m , while the declination coordinates are between −36.31° and −56.39°.[1] Grus is located too far south to be seen by observers in the British Isles and the northern United States, though it can easily be seen from Florida or San Diego;[9] the whole constellation is visible to observers south of latitude 33°N.[10][a]

Features[edit]

Stars[edit]

Keyser and de Houtman assigned twelve stars to the constellation.[11] Bayer depicted Grus on his chart, but did not assign its stars Bayer designations. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille labelled them Alpha to Phi in 1756 with some omissions. In 1879, American astronomer Benjamin Gould added Kappa, Nu, Omicron and Xi, which had all been catalogued by Lacaille but not given Bayer designations. Lacaille considered them too faint, while Gould thought otherwise. Xi Gruis had originally been placed in Microscopium. Conversely, Gould dropped Lacaille's Sigma as he thought it was too dim.[12]

Grus has several bright stars. Marking the left wing is Alpha Gruis,[11] a blue-white star of spectral type B6V and apparent magnitude 1.7, around 101 light-years from Earth.[13] Its traditional name, Alnair, means "the bright one" and refers to its status as the brightest star in Grus (although the Arabians saw it as the brightest star in the Fish's tail, as Grus was then depicted).Alnair Alnair is around 380 times as luminous and has over 3 times the diameter of the Sun.[14] Lying 5 degrees west of Alnair,[15] denoting the Crane's heart is Beta Gruis[11] (the proper name is Tiaki[16]), a red giant of spectral type M5III.[17] It has a diameter of 0.8 astronomical units (AU) (if placed in the Solar System it would extend to the orbit of Venus) located around 170 light-years from Earth. It is a variable star with a minimum magnitude of 2.3 and a maximum magnitude of 2.0.[18] An imaginary line drawn from the Great Square of Pegasus through Fomalhaut will lead to Alnair and Beta Gruis.[9]

Lying in the northwest corner of the constellation and marking the crane's eye is Gamma Gruis,[15] a blue-white subgiant of spectral type B8III and magnitude 3.0 lying around 211 light-years from Earth.[19] Also known as Al Dhanab,[16] it has finished fusing its core hydrogen and has begun cooling and expanding, which will see it transform into a red giant.[20]

There are several double stars visible to the naked eye in Grus. Forming a triangle with Alnair and Beta, Delta Gruis is an optical double whose components—Delta1 and Delta2—are separated by 45 arcseconds.[15] Delta1 is a yellow giant of spectral type G7III and magnitude 4.0, 309 light-years from Earth,[21] and may have its own magnitude 12 orange dwarf companion.[22] Delta2 is a red giant of spectral type M4.5III and semiregular variable that ranges between magnitudes 3.99 and 4.2,[23] located 325 light-years from Earth. It has around 3 times the mass and 135 times the diameter of the Sun.[22] Mu Gruis, composed of Mu1 and Mu2, is also an optical double—both stars are yellow giants of spectral type G8III around 2.5 times as massive as the Sun with surface temperatures of around 4900 K.[24] Mu1 is the brighter of the two at magnitude 4.8 located around 275 light-years from Earth,[25] while Mu2 the dimmer at magnitude 5.11 lies 265 light-years distant from Earth.[26] Pi Gruis, an optical double with a variable component, is composed of Pi1 Gruis and Pi2. Pi1 is a semi-regular red giant of spectral type S5, ranging from magnitude 5.31 to 7.01 over a period of 191 days,[27] and is around 532 light-years from Earth.[28] One of the brightest S-class stars to Earth viewers, it has a companion star of apparent magnitude 10.9 with sunlike properties, being a yellow main sequence star of spectral type G0V. The pair make up a likely binary system.[29] Pi2 is a giant star of spectral type F3III-IV located around 130 light-years from Earth,[30] and is often brighter than its companion at magnitude 5.6.[31] Marking the right wing is Theta Gruis,[11] yet another double star, lying 5 degrees east of Delta1 and Delta2.[15]

RZ Gruis is a binary system of apparent magnitude 12.3 with occasional dimming to 13.4, whose components—a white dwarf and main sequence star—are thought to orbit each other roughly every 8.5 to 10 hours. It belongs to the UX Ursae Majoris subgroup of cataclysmic variable star systems, where material from the donor star is drawn to the white dwarf where it forms an accretion disc that remains bright and outshines the two component stars. The system is poorly understood,[32] though the donor star has been calculated to be of spectral type F5V.[33] These stars have spectra very similar to novae that have returned to quiescence after outbursts, yet they have not been observed to have erupted themselves. The American Association of Variable Star Observers recommends watching them for future events.[34] CE Gruis (also known as Grus V-1) is a faint (magnitude 18–21) star system also composed of a white dwarf and donor star; in this case the two are so close they are tidally locked. Known as polars, material from the donor star does not form an accretion disc around the white dwarf, but rather streams directly onto it.[35]

Six star systems are thought to have planetary systems. Tau1 Gruis is a yellow star of magnitude 6.0 located around 106 light-years away.[36] It may be a main sequence star or be just beginning to depart from the sequence as it expands and cools. In 2002 the star was found to have a planetary companion.[37] HD 215456, HD 213240 and WASP-95 are yellow sunlike stars discovered to have two planets,[38] a planet and a remote red dwarf,[39] and a hot Jupiter, respectively; this last—WASP-95b—completes an orbit round its sun in a mere two days.[40] Gliese 832 is a red dwarf of spectral type M1.5V and apparent magnitude 8.66 located only 16.1 light-years distant; hence it is one of the nearest stars to the Solar System. A Jupiter-like planet—Gliese 832 b—orbiting the red dwarf over a period of 9.4±0.4 years was discovered in 2008.[41] WISE 2220−3628 is a brown dwarf of spectral type Y, and hence one of the coolest star-like objects known. It has been calculated as being around 26 light-years distant from Earth.[42]

In July 2019, astronomers reported finding a star, S5-HVS1, traveling 1,755 km/s (3,930,000 mph), faster that any other star detected so far. The star is in the Grus constellation in the southern sky, and about 29,000 light-years from Earth, and may have been propelled out of the Milky Way galaxy after interacting with Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy.[43][44][45][46]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

Nicknamed the spare-tyre nebula,[47] IC 5148 is a planetary nebula located around 1 degree west of Lambda Gruis.[48] Around 3000 light-years distant, it is expanding at 50 kilometres a second, one of the fastest rates of expansion of all planetary nebulae.[47]

Northeast of Theta Gruis are four interacting galaxies known as the Grus Quartet.[49] These galaxies are NGC 7552, NGC 7590, NGC 7599, and NGC 7582.[50] The latter three galaxies occupy an area of sky only 10 arcminutes across and are sometimes referred to as the "Grus Triplet," although all four are part of a larger loose group of galaxies called the IC 1459 Grus Group.[51] NGC 7552 and 7582 are exhibiting high starburst activity; this is thought to have arisen because of the tidal forces from interacting.[50] Located on the border of Grus with Piscis Austrinus,[48] IC 1459 is a peculiar E3 giant elliptical galaxy. It has a fast counterrotating stellar core, and shells and ripples in its outer region.[52] The galaxy has an apparent magnitude of 11.9[53] and is around 80 million light-years distant.[48]

NGC 7424 is a barred spiral galaxy with an apparent magnitude of 10.4.[54] located around 4 degrees west of the Grus Triplet.[48] Approximately 37.5 million light-years distant, it is about 100,000 light-years in diameter, has well defined spiral arms and is thought to resemble the Milky Way.[55] Two ultraluminous X-ray sources and one supernova have been observed in NGC 7424.[56] SN 2001ig was discovered in 2001 and classified as a Type IIb supernova, one that initially showed a weak hydrogen line in its spectrum, but this emission later became undetectable and was replaced by lines of oxygen, magnesium and calcium, as well as other features that resembled the spectrum of a Type Ib supernova.[57] A massive star of spectral type F, A or B is thought to be the surviving binary companion to SN 2001ig, which was believed to have been a Wolf–Rayet star.[58]

Located near Alnair is NGC 7213,[48] a face-on type 1 Seyfert galaxy located approximately 71.7 million light-years from Earth.[59] It has an apparent magnitude of 12.1.[60] Appearing undisturbed in visible light, it shows signs of having undergone a collision or merger when viewed at longer wavelengths, with disturbed patterns of ionized hydrogen including a filament of gas around 64,000 light-years long.[59] It is part of a group of ten galaxies.[61]

NGC 7410 is a spiral galaxy discovered by British astronomer John Herschel during observations at the Cape of Good Hope in October 1834. The galaxy has a visual magnitude of 11.7 and is approximately 122 million light-years distant from Earth.[51]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "Grus, Constellation Boundary". The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Ridpath, Ian. "Grus". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Bayer's Southern Star Chart". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ Ridpath, Ian. "Frederick de Houtman's catalogue". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Moore, Patrick (2000). Exploring the Night Sky with Binoculars. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-521-79390-2.

- ^ Johnson, Diane (1998). Night Skies of Aboriginal Australia: a Noctuary. Darlington, New South Wales: University of Sydney. pp. 70–72. ISBN 1-86451-356-X.

- ^ Bagnall, Philip M. (2012). The Star Atlas Companion: What You Need to Know about the Constellations. New York, New York: Springer. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4614-0830-7.

- ^ Russell, Henry Norris (1922). "The New International Symbols for the Constellations". Popular Astronomy. 30: 469. Bibcode:1922PA.....30..469R.

- ^ a b Moore, Patrick (2001). Stargazing: Astronomy Without a Telescope. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0-521-79445-5.

Grus constellation visibility.

- ^ a b Ridpath, Ian. "Constellations: Andromeda–Indus". Star Tales. self-published. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Knobel, Edward B. (1917). "On Frederick de Houtman's Catalogue of Southern Stars, and the Origin of the Southern Constellations". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 77 (5): 414–32 [430]. Bibcode:1917MNRAS..77..414K. doi:10.1093/mnras/77.5.414.

- ^ Wagman, Morton (2003). Lost Stars: Lost, Missing and Troublesome Stars from the Catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and Sundry Others. Blacksburg, Virginia: The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company. pp. 360–62. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ^ "Alpha Gruis – High Proper-motion Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Al Nair". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Motz, Lloyd; Nathanson, Carol (1991). The Constellations: An Enthusiast's Guide to the Night Sky. London, United Kingdom: Aurum Press. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-85410-088-7.

- ^ a b "Naming Stars". IAU.org. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Beta Gruis – Pulsating Variable Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Beta Gruis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ "Gamma Gruis". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Al Dhanab". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "HR 8556 – Star in double system". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ a b Kaler, James B. "Delta Gruis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Watson, Christopher (25 August 2009). "Delta 2 Gruis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ Kaler, James B. "Mu Gruis". Stars. University of Illinois. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "HR 8486". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "HR 8488". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Otero, Sebastian Alberto (20 June 2011). "Pi 1 Gruis". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ "Pi1 Gruis – S Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Sacuto, S.; Jorissen, A.; Cruzalèbes, P.; Chesneau, O.; Ohnaka, K.; Quirrenbach, A.; Lopez, B. (2008). "The close circumstellar environment of the semi-regular S-type star π 1 Gruis" (PDF). Astronomy & Astrophysics. 482 (2): 561–74. arXiv:0803.3077. Bibcode:2008A&A...482..561S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078306. S2CID 14085392. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-13.

- ^ "LTT 8994 – High proper-motion Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 19 January 2014.

- ^ Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Bisol, Alexandra C.; Godon, Patrick; Sion, Edward M. (2012). "Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopy of Three Long Period Nova-Like Variables". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 124 (912): 158–63. arXiv:1112.3711. Bibcode:2012PASP..124..158B. doi:10.1086/664464. S2CID 116536811.

- ^ Stickland, D.J.; Kelly, B.D.; Cooke, J.A.; Coulson, I.; Engelbrecht, C.; Kilkenny, D. (1984). "RZ Gru – A UX UMa 'disc star'". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 206 (4): 819–31. Bibcode:1984MNRAS.206..819S. doi:10.1093/mnras/206.4.819.

- ^ Malatesta, Kerri (17 July 2010). "UX Ursae Majoris". Variable Star of the Season. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ Ramsay, Gavin; Cropper, Mark (2002). "First X-ray Observations of the Polar CE Gru". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 335 (4): 918–22. arXiv:astro-ph/0205102. Bibcode:2002MNRAS.335..918R. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2002.05666.x. S2CID 8460918.

- ^ "Tau1 Gruis -- High proper-motion Star". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- ^ Jones, R. Paul; Butler, Hugh R. A.; Tinney, C. G.; Marcy, Geoffrey W.; Penny, Alan J.; McCarthy, Chris; Carter, Brad D. (2003). "An Exoplanet in Orbit around τ1 Gruis". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 341 (3): 948–52. arXiv:astro-ph/0209302. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.341..948J. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06481.x. S2CID 1575040.

- ^ Mayor, M.; et al. (2011). "The HARPS Search for Southern Extra-solar Planets XXXIV. Occurrence, Mass Distribution and Orbital Properties of Super-Earths and Neptune-mass Planets". arXiv:1109.2497 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Mugrauer, M.; Neuhäuser, R.; Seifahrt, A.; Mazeh, T.; Guenther, E. (2005). "Four New Wide Binaries Among Exoplanet Host Stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 440 (3): 1051–60. arXiv:astro-ph/0507101. Bibcode:2005A&A...440.1051M. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042297. S2CID 14065040.

- ^ Hellier, Coel; Anderson, D.R.; Collier Cameron, A.; Delrez, L.; Gillon, M.; Jehin, E.; Lendl, M.; Maxted, P.F.L.; Pepe, F.; Pollacco, D.; Queloz, D.; Segransan, D.; Smalley, B.; Smith, A.M.S.; Southworth, J.; Triaud, A.H.M.J.; Udry, S.; West, R.G. (2014). "Transiting Hot Jupiters from WASP-South, Euler and TRAPPIST: WASP-95b to WASP-101b". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 440 (3): 1982–92. arXiv:1310.5630. Bibcode:2014MNRAS.440.1982H. doi:10.1093/mnras/stu410. S2CID 54977201.

- ^ Bailey, J.; Butler, R.P.; Tinney, C.G.; Jones, H.R.A.; O'Toole, S.; Carter, B.D.; Marcy, G. W. (2009). "A Jupiter-like Planet Orbiting the Nearby M Dwarf GJ832". The Astrophysical Journal. 690 (1): 743–47. arXiv:0809.0172. Bibcode:2009ApJ...690..743B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/690/1/743. S2CID 17172233.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, J. Davy; Gelino, Christopher R.; Cushing, Michael C.; Mace, Gregory N.; Griffith, Roger L.; Skrutskie, Michael F.; Marsh, Kenneth A.; Wright, Edward L.; Eisenhardt, Peter R.; McLean, Ian S.; Mainzer, Amy K.; Burgasser, Adam J.; Tinney, Chris G.; Parker, Stephen; Salter, Graeme (2012). "Further Defining Spectral Type "Y" and Exploring the Low-mass End of the Field Brown Dwarf Mass Function". The Astrophysical Journal. 753 (2): 156. arXiv:1205.2122. Bibcode:2012ApJ...753..156K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/753/2/156. S2CID 119279752.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (14 November 2019). "A Black Hole Threw a Star Out of the Milky Way Galaxy - So long, S5-HVS1, we hardly knew you". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-01-02. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Koposov, Sergey E.; et al. (11 November 2019). "Discovery of a nearby 1700 km/s star ejected from the Milky Way by Sgr A*". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. arXiv:1907.11725. doi:10.1093/mnras/stz3081. S2CID 198968336.

- ^ Starr, Michelle (31 July 2019). "Bizarre Star Found Hurtling Out of Our Galaxy Centre Is Fastest of Its Kind Ever Seen". ScienceAlert.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Irving, Michael (13 November 2019). "Fastest star ever found is being flicked out of the Milky Way". NewAtlas.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ a b ESO (2012). "From Cosmic Spare Tyre to Ethereal Blossom". Picture of the Week. European Southern Observatory. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Streicher, Magda (December 2010). "Grus—An Elegant Starry Bird" (PDF). Deepsky Delights. The Astronomical Society of Southern Africa. pp. 56–59. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Bakich, Michael E. (2010). 1,001 Celestial Wonders to See Before You Die. New York, New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-4419-1777-5.

- ^ a b Koribalski, Bärbel (1996). "The Grus-Quartet". Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ a b O'Meara, Stephen James (2013). Deep Sky Companions: Southern Gems. New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 418–26. ISBN 978-1-107-01501-2.

- ^ Verdoes Kleijn, Gijs A.; van der Marel, Roeland P.; Carollo, C. Marcella; de Zeeuw, P. Tim (2000). "The Black Hole in IC 1459 from Hubble Space Telescope Observations of the Ionized Gas Disk". The Astronomical Journal. 120 (3): 1221–37. arXiv:astro-ph/0003433. Bibcode:2000AJ....120.1221V. doi:10.1086/301524.

- ^ "IC 1459 – LINER-type Active Galaxy Nucleus". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ "NGC 7424 – Galaxy in Group of Galaxies". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (8 January 2013). "Grand Spiral Galaxy NGC 7424". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 4 February 2014.

- ^ Soria, R.; Kuncic, Z.; Broderick, J. W.; Ryder, S. D. (2006). "Multiband Study of NGC 7424 and its Two Newly-discovered ULXs". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 370 (4): 1666–76. arXiv:astro-ph/0606080. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.370.1666S. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10629.x. S2CID 17098189.

- ^ Maund, Justyn R.; Wheeler, J. Craig; Patat, Ferdinando; Wang, Lifan; Baade, Dietrich; Höflich, Peter A. (2007). "Spectropolarimetry of the Type IIb Supernova 2001ig*". The Astrophysical Journal. 671 (2): 1944–1958. arXiv:0709.1487. Bibcode:2007ApJ...671.1944M. doi:10.1086/523261. S2CID 15234633.

- ^ Ryder, Stuart D.; Murrowood, Clair E.; Stathakis, Raylee A. (2006). "A Post-mortem Investigation of the Type IIb Supernova 2001ig". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 369 (1): L32–L36. arXiv:astro-ph/0603336. Bibcode:2006MNRAS.369L..32R. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3933.2006.00168.x. S2CID 15543433.

- ^ a b Hameed, Salman; Blank, David L.; Young, Lisa M.; Devereux, Nick (2001). "The Discovery of a Giant Hα Filament in NGC 7213" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 546 (2): L97–L100. arXiv:astro-ph/0011208. Bibcode:2001ApJ...546L..97H. doi:10.1086/318865. S2CID 2657286. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-24.

- ^ "NGC 7213 – Type 1 Seyfert Galaxy". SIMBAD Astronomical Database. Centre de Données astronomiques de Strasbourg. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- ^ Fouque, P.; Proust, D.; Quintana, H.; Ramirez, A. (1993). "Dynamics of the Pavo-Indus and Grus Clouds of Galaxies". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 100 (3): 493–500. Bibcode:1993A&AS..100..493F.

Cited text[edit]

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2