HMS Agincourt (1865)

Agincourt at anchor

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | HMS Agincourt |

| Namesake | Battle of Agincourt |

| Ordered | 2 September 1861 |

| Builder | Laird, Son & Co., Birkenhead |

| Cost | £483,003 |

| Laid down | 30 October 1861 |

| Launched | 27 March 1865 |

| Completed | 19 December 1868 |

| Commissioned | June 1868 |

| Decommissioned | 1889 |

| Out of service | Hulked, 1909 |

| Renamed |

|

| Reclassified | Training ship, 1893 |

| Refit | 1875–77 |

| Fate | Broken up, 21 October 1960 |

| General characteristics (as completed) | |

| Class and type | Minotaur-class armoured frigate |

| Displacement | 10,627 long tons (10,798 t) |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 59 ft 6 in (18.1 m) |

| Draught | 26 ft 10 in (8.2 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | |

| Sail plan | 5-masted |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Range | 1,500 nmi (2,800 km; 1,700 mi) at 7.5 kn (13.9 km/h; 8.6 mph) |

| Complement | 800 actual |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Agincourt was a Minotaur-class armoured frigate built for the Royal Navy during the 1860s. She spent most of her career as the flagship of the Channel Squadron's second-in-command. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, she was one of the ironclads sent to Constantinople to forestall a Russian occupation of the Ottoman capital. Agincourt participated in Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee Fleet Review in 1887. The ship was placed in reserve two years later and served as a training ship from 1893 to 1909. That year she was converted into a coal hulk and renamed as C.109. Agincourt served at Sheerness until sold for scrap in 1960.

Design and description

The three Minotaur-class armoured frigates[Note 1] were essentially enlarged versions of the ironclad HMS Achilles with heavier armament, armour, and more powerful engines. They retained the broadside ironclad layout of their predecessor, but their sides were fully armoured to protect the 50 guns they were designed to carry. Their plough-shaped ram was also more prominent than that of Achilles.[1]

The ships were 400 feet (121.9 m) long between perpendiculars and 407 feet (124.1 m) long overall. They had a beam of 58 feet 6 inches (17.8 m) and a draft of 26 feet 10 inches (8.2 m).[2] The Minotaur-class ships displaced 10,627 long tons (10,798 t).[3] Their hull was subdivided by 15 watertight transverse bulkheads and had a double bottom underneath the engine and boiler rooms.[4]

Agincourt was considered "an excellent sea-boat and a steady gun platform, but unhandy under steam and practically unmanageable under sail"[5] as built. The ship's steadiness was partially a result of her metacentric height of 3.87 feet (1.2 m).[6]

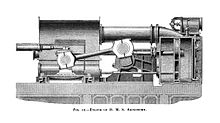

Propulsion

Agincourt had one 2-cylinder horizontal return connecting rod-steam engine, made by Maudslay, driving a single propeller using steam provided by 10 rectangular fire-tube boilers. It produced a total of 4,426 indicated horsepower (3,300 kW) during the ship's sea trials on 12 December 1865 and Agincourt had a maximum speed of 13.55 knots (25.09 km/h; 15.59 mph). The ship carried 750 long tons (760 t) of coal,[7] enough to steam 1,500 nautical miles (2,800 km; 1,700 mi) at 7.5 knots (13.9 km/h; 8.6 mph).[4]

Agincourt had five masts and a sail area of 32,377 square feet (3,008 m2). Agincourt only made 9.5 knots (17.6 km/h; 10.9 mph) under sail mainly because the ship's propeller could only be disconnected and not hoisted up into the stern of the ship to reduce drag. Both funnels were semi-retractable to reduce wind resistance while under sail.[8] Admiral George A. Ballard described Agincourt and her sisters as "the dullest performers under canvas of the whole masted fleet of their day, and no ships ever carried so much dress to so little purpose."[9] In 1893–1894, after her withdrawal from active service, Agincourt had two masts removed and was re-rigged as a barque.[6] In 1907 the upper portions of one of her masts was installed at the shore establishment HMS Ganges for use in the training of boy seamen.[10]

Armament

The armament of the Minotaur-class ships was intended to be 40 rifled 110-pounder breech-loading guns on the main deck and 10 more on the upper deck on pivot mounts. The gun was a new design from Armstrong, but proved a failure a few years after its introduction. The gun was withdrawn before any were received by any of the Minotaur-class ships. They were armed, instead, with a mix of seven-inch (178 mm) and nine-inch (229 mm) rifled muzzle-loading guns. All 4 nine-inch and 20 seven-inch guns were mounted on the main deck while 4 seven-inch guns were fitted on the upper deck as chase guns. The ship also received eight brass howitzers for use as saluting guns. The gun ports were 30 inches (0.8 m) wide which allowed each gun to fire 30° fore and aft of the beam.[11]

The shell of the nine-inch gun weighed 254 pounds (115.2 kg) while the gun itself weighed 12 long tons (12 t). It had a muzzle velocity of 1,420 ft/s (430 m/s) and was credited with the ability to penetrate a 11.3 inches (287 mm) of wrought iron armour at the muzzle. The seven-inch gun weighed 6.5 long tons (6.6 t) and fired a 112-pound (50.8 kg) shell. It was credited with the ability to penetrate 7.7-inch (196 mm) armour.[12]

Agincourt was rearmed in 1875 with a uniform armament of 17 nine-inch guns, 14 on the main deck, 2 forward chase guns and 1 rear chase gun. The gun ports had to be enlarged to accommodate the larger guns by hand, at a cost of £250 each. About 1883 two six inches (152 mm) breech-loading guns replaced 2 nine-inch muzzle-loading guns.[13] Four quick-firing (QF) 4.7-inch (120-mm) guns, eight QF 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns, eight machine guns and two torpedo tubes were installed in 1891–2.[14]

Armour

The entire side of the Minotaur-class ships was protected by wrought iron armour that tapered from 4.5 inches (114 mm) at the ends to 5.5 inches (140 mm) amidships, except for a section of the bow between the upper and main decks. The armour extended 5 feet 9 inches (1.8 m) below the waterline. A single 5.5-inch transverse bulkhead protected the forward chase guns on the upper deck. The armour was backed by 10 inches (254 mm) of teak.[14]

Construction and service

HMS Agincourt, named after the victory at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415,[15] was originally ordered on 2 September 1861 as HMS Captain, but her name was changed during construction. She was laid down on 30 October 1861 by Laird's at its shipyard in Birkenhead. The ship was launched on 27 March 1865, commissioned in June 1868 for sea trials and completed on 19 December. The lengthy delay in completion was due to frequent changes in design details, and experiments with her armament and with her sailing rig.[16] The ship cost a total of £483,003.[17]

Agincourt's first assignment, together with her half-sister[Note 2] Northumberland, was to tow a floating drydock from England to Madeira where it would be picked up by Warrior and Black Prince and taken to Bermuda. The ships departed the Nore on 23 June 1869, loaded down with 500 long tons (510 t) of coal stowed in bags on their gun decks, and transferred the floating dock 11 days later after an uneventful voyage. Agincourt was assigned to the Channel Squadron upon her return and she became the flagship of the second-in-command of the fleet until she began a refit in 1873.[18]

1871 grounding on Pearl Rock

It was during this assignment that she suffered a near-catastrophe when she ran aground on Pearl Rock, near Gibraltar on 1 July 1871 and nearly sank. Agincourt was leading the inshore column of ships, contrary to normal practice where the senior flagship lead the inshore column, and gently ran aground sideways when the senior flagship's navigator failed to compensate for the set of the tide. Warrior, immediately following her, nearly collided with her, but managed to sheer off in time.[19][20]

Agincourt was stuck fast and had to be lightened; her guns were removed and much of her coal was tossed overboard before she was towed off by Hercules, commanded by Lord Gilford, four days later. Heavy weather set in the night after Agincourt was freed and it would have wrecked her if she had still been aground. Both the fleet commander and his deputy were relieved of their commands as a result of the incident. The ship was repaired in Devonport at a cost of £1,195 and Captain J.O. Hopkins assumed command in September with Commander Charles Penrose-Fitzgerald as his executive officer. Hopkins later commented: "We turned the Agincourt from the noisiest and the worst disciplined ship in the squadron into the quietest and the smartest; and a few months after we commissioned we went out to the Mediterranean for the Lord Clyde court-martial, and beat the whole Mediterranean fleet in their drills and exercises, which was a great triumph."[21][22]

In 1873, Vice Admiral Sir Geoffrey Hornby, commander of the Channel Squadron, transferred his flag to Agincourt as her sister Minotaur, his former flagship, was taken in hand for a refit that lasted until 1875. That year Agincourt was paid off in turn for a refit and re-armament that lasted until 1877. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, the government became concerned that the Russians might advance on the Ottoman capital of Constantinople and ordered Hornby to form a Particular Service Squadron to show the flag at Constantinople and deter any Russian threat. Agincourt served as the flagship for his second-in-command and the squadron sailed up the Dardanelles in a blinding snowstorm in February 1878. After those tensions faded, the ship returned to the Channel, where she served as second flag until 1889 including during Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee Fleet Review in 1887. Over her active career, she served as flagship to no fewer than 15 admirals. That year she was again paid off and was subsequently held in reserve at Portsmouth until 1893, when she was transferred to Portland for use as a training ship.[23]

Agincourt served twelve years at Portland, as a depot ship for boys. She was renamed Boscawen III in March, 1904.[24] In 1905 she was moved to Harwich and renamed as Ganges II. After four years at Harwich, Ganges II made her final journey, to Sheerness, in 1909. After her arrival the old ship was converted into a coal hulk known simply as C.109. After five ignominious decades as what naval historian Oscar Parkes called "a grimy, dilapidated and incredibly shrunken relic"[25] of her former self, she was scrapped beginning on 21 October 1960.[23]

Notes

- ^ Ironclad is the all-encompassing term for armoured warships of this period. Armoured frigates were basically designed for the same role as traditional wooden frigates, but this later changed as the size and expense of these ships forced them to be used in the line of battle.

- ^ A half-sister is a ship that generally resembles the rest of her class, but has been altered in one or more significant ways like a different armour scheme, number of propeller shafts, type of engine, etc.

Footnotes

- ^ Parkes, pp. 60–61

- ^ Silverstone, p. 157

- ^ Ballard, p. 241

- ^ a b Parkes, p. 60

- ^ Ballard, p. 24

- ^ a b Parkes, p. 63

- ^ Ballard, pp. 28, 246–247

- ^ Parkes, pp. 60, 63

- ^ Ballard, p. 26

- ^ "Ceremonial Mast of the Former HMS Ganges, Royal Naval Training Establishment, Shotley". Historic England.

- ^ Parkes, p. 61

- ^ Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 6

- ^ Parkes, p. 62

- ^ a b Chesneau & Kolesnik, p. 10

- ^ Silverstone, p. 208

- ^ Ballard, pp. 28, 240

- ^ Parkes, p. 59

- ^ Ballard, pp. 31, 33

- ^ Penrose-Fitzgerald, pp. 299–300

- ^ "Latest Shipping Intelligence". The Times. No. 27106. London. 4 July 1871. col D, p. 11.

- ^ Penrose-Fitzgerald, pp. 300–02, 305–06

- ^ "Naval Disasters Since 1860". Hampshire Telegraph. No. 4250. Portsmouth. 10 May 1873.

- ^ a b Ballard, p. 33

- ^ See Portsmouth Evening News (Friday, 25 March 1904), p. 3.

- ^ Parkes, p. 64

References

- Ballard, G. A., Admiral (1980). The Black Battlefleet. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-924-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Brown, David K. (2003). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905 (reprint of the 1997 ed.). London: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-529-2.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Penrose-Fitzgerald, Charles Cooper (1913). Memories of the Sea. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 10689448.