History of Baghdad

The history of Baghdad begins when the city of Baghdad (Template:Lang-ar Baġdād) was found in the mid 8th century as the Abbasid capital, following the Abbasid victory over the Umayyad Caliphate. It replaced the Sassanid capital of Seleucia-Ctesiphon some 35 km to the south-east, which was mostly depopulated by the end of the 8th century. Baghdad was the center of the Arab caliphate during the "Golden Age of Islam" of the 9th and 10th centuries, growing to be the largest city worldwide by the beginning of the 10th century. It began to decline in the "Iranian Intermezzo" of the 9th to 11th centuries, and was destroyed in the Mongolian invasion in 1258.

The city was rebuilt and flourished under Ilkhanid rule but never rose to its former glory again. It was again sacked by Timur in 1401 and fell under Turkic rule. It was briefly taken by Safavid Persia in 1508, before falling to the Ottoman Empire in 1534. With the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Baghdad fell under the British Mandate in 1920 and became the capital of the independent Kingdom of Iraq in 1932 (converted to a Republic in 1958).

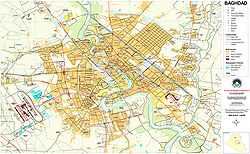

As the capital of the modern Republic of Iraq, Baghdad has a metropolitan area estimated at a population of 7,000,000 divided into numerous neighbourhoods in nine districts. It is the largest city in Iraq. It is the second-largest city in the Arab world (after Cairo) and the second-largest city in Western Asia (after Tehran). In recent history, Baghdad has been affected by the Iraqi civil war, most notably by recurring bombings.

Early history

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (September 2016) |

Baghdad was founded 1,259 years ago on the 30 July 762. It was designed by caliph Al-Mansur.[citation needed] According to 11th-century scholar Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi – each course consisted of 162,000 bricks for the first third of the wall's heigh wall was 80ft high, crowned with battlements and flanked by bastions. A deep moat ringed the outer wall perimeter.

Thousands of architects and engineers, legal experts, surveyors and carpenters, blacksmiths, diggers and ordinary labourers were recruited from across the Abbasid empire. First they surveyed, measured and excavated the foundations. Ya'qubi reckoned there were 100,000 workers involved. "They say that no other round city is known in all the regions of the world," Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi noted. Four equidistant gates pierced the outer walls where straight roads led to the centre of the city. The Kufa Gate to the south-west and the Basra Gate to the south-east both opened on to the Sarat canal – a key part of the network of waterways that drained the waters of the Euphrates into the Tigris. The Sham (Syrian) Gate to the north-west led to the main road on to Anbar, and across the desert wastes to Syria. To the north-east the Khorasan Gate lay close to the Tigris, leading to the bridge of boats across it.

The four straight roads that ran towards the centre of the city from the outer gates were lined with vaulted arcades containing merchants' shops and bazaars. Smaller streets ran off these four main arteries, giving access to a series of squares and houses; the limited space between the main wall and the inner wall answered to Mansur's desire to maintain the heart of the city as a royal preserve.

By 766 Mansur's Round City was complete. The ninth-century essayist, polymath and polemicist al-Jahiz said. "I have seen the great cities, including those noted for their durable construction. I have seen such cities in the districts of Syria, in Byzantine territory, and in other provinces, but I have never seen a city of greater height, more perfect circularity, more endowed with superior merits or possessing more spacious gates or more perfect defenses than Al Zawra (Baghdad), that is to say the city of Abu Jafar al-Mansur.

The city had an impressive array of basic services and employed a large staff of civil servants. These included night watchmen, lamplighters, health inspectors, market inspectors (who examined the weights and measures as well as the quality of goods), and debt collectors. It also had a police force with a police chief who lived in the caliph's palace.[1]

Destruction and abandonment

The Round City was partially ruined during the siege of 812–813, when caliph Al-Amin was killed by his brother,[a] who then became the new caliph. It never recovered;[b] its walls were destroyed by 912,[c] nothing of them remain,[d][3] and there is no agreement as to where it was located.[4]

Center of learning (8th to 9th centuries)

Founder, caliph al-Mansur of the Abbasid caliphate, chose the city's location because of its critical link in trade routes, mild climate, topography (critical for fortification), and proximity to water. All of these factors made the city a breeding ground of culture and knowledge. Baghdad is set right on the Khurasan Road, which was an established meeting place for caravan routes from all cardinal directions.[5] During the construction of the city, gates were placed at the entrances of the major roads into the city, in order to funnel traffic into the city. The Kufah Gate was on a major road that pilgrims took to Mecca, and the Anbar gate linked the bridges over the canals and Euphrates River to the city. These were a substantial help at bringing people into the city, and around these entrances markets sprang up for travellers to trade at.[6] The link in trade routes provided a flood of goods into the city, which allowed numerous markets to spring up drawing people from all of the Middle East to Baghdad to trade. The markets that developed in Baghdad were some of the most sophisticated as well because of the government's supervision of their products as well as trade amongst each other.[5] Because of the sophisticated trading market, an advanced banking system developed as well, allowing further settlement from outsiders. Baghdad's location between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as well, created a trade link to further destinations such as China, India and Armenia, drawing even more people, literature, and knowledge to the city from exotic and distant lands.[7] The mild climate and topography made it easy to settle as well for travellers coming to the city to trade. As Baghdad became a trading hub in the Islamic Empire, cultures collided, sharing knowledge, books, language, and faiths, ultimately creating a "cosmopolitan city" that developed into a learning center for the world.[8]

As more and more people began to settle in the city, numerous schools began to spring up including the Hanafi and Hanbali schools of law. Law being a critical study for the Muslim people, because of the understanding of justice on Earth as applied to God.[5] The Hanafi is currently the largest school of legal thought in the Muslim world, and it was a major draw for scholars to the city of Baghdad. Another important school in Baghdad that began was the Bayt al-Hikma (House of Wisdom), which focused on translating texts from various languages into Arabic. This practice began out of a need to supply educated texts from around the world to a growing educated public market.[9] In particular the Arabic translation of Grecian texts became a substantial market that was quite progressive because its primary impetus from the caliphate was to establish a new ideology with a political and scientific base.[10] This translation helped to foster the transition between a primarily oral society, to one centered on a written language. Baghdad's location also made it ideal for paper production, which lowered the cost of creating books, making them more prevalent and accessible to more people.[8] As more and more texts began to be produced as well, a new market for book vendors opened up, and numerous libraries and bookstores sprang up in the city. As the public and private sectors of the community became more educated, cultural narrative and secular writing began. In the city, a demand for secular literature, designed for entertainment, developed, which shaped the culture of the city's population, as well as the Abbasid Empire as a whole, with Baghdad being their crowning achievement and reason for the Golden Age of Islam.[11] At this time, Baghdad was revered as the "center of the world" because of its scholarship. Michael Cooperson says that "Baghdadi scholars were so numerous and so eminent that reference to them could continue to support the 'center of the world' thesis…".[12] The influx of trade and commerce brought these scholars to the city, and made it the cosmopolitan breeding ground of knowledge that it became. Al-Mansur's foundation and construction of the city as well, was done by only the best and brightest scholars, further fostering the notion of a highly intellectual city population to support the Golden Age.[13] At the height of the golden age in Baghdad, it was estimated that there were over one and half million people living in the city.[14]

Al-Mansur's foundation of the city was ultimately based on its potential position as a military arsenal, and its ability to house and support many troops. Large numbers of troops were what originally gave the city such a dense population, but as the army continued to need supplies more and more people flooded to the city for jobs, thus being another reason Baghdad became a center of commerce.[15] Baghdad also being named the new capital of the Abbasid caliphate drew numerous people in for the prestige and name alone. Al-Mansur designated a governor of Baghdad and sent with him a number of elites who gave the city a higher status and poise, drawing more and more scholars to study in such a well-educated and cosmopolitan city.[16] Baghdad grew and developed in a variety of facets, and because of this it arguably became the largest city in the world during that time.

Stagnation and invasions (10th to 16th centuries)

By the 10th century, the city's population was between 300,000 and 500,000.[citation needed] Baghdad's early meteoric growth slowed due to troubles within the Caliphate, including relocations of the capital to Samarra (during 808–819 and 836–892), the loss of the western and easternmost provinces, and periods of political domination by the Iranian Buwayhids (945–1055) and Seljuk Turks (1055–1135). Nevertheless, the city remained one of the cultural and commercial hubs of the Islamic world until February 10, 1258, when it was sacked by the Mongols under Hulagu Khan during the sack of Baghdad. The Mongols massacred most of the city's inhabitants, including the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta'sim, and destroyed large sections of the city. The canals and dykes forming the city's irrigation system were also destroyed. The sack of Baghdad put an end to the Abbasid Caliphate, a blow from which the Islamic civilization never fully recovered.

At this point Baghdad was ruled by the Il-Khanids, part of the Mongolian Empire centred in Iran. The city was reconstructed and flourished under the Mongols. In 1401, Baghdad was again conquered, by Timur ("Tamerlane"). It became a provincial capital controlled by the Jalayirid (1400–1411), Qara Qoyunlu (1411–1469), Aq Quyunlu (1469–1508), and Safavid Persian (1508–1534) - (1604–1638) empires.

Ottoman Baghdad (16th to 19th centuries)

In 1534, Baghdad was conquered by the Ottoman Turks. Under the Ottomans, Baghdad fell into a period of decline, partially as a result of the enmity between its rulers and Persia. For a time, Baghdad had been the largest city in the Middle East before being overtaken by Constantinople in the 16th century. The city saw relative revival in the latter part of the 18th century under the Mamluk dynasty. The Nuttall Encyclopedia reports the 1907 population of Baghdad as 185,000.

20th and 21st centuries

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

This article appears to be slanted towards recent events. (July 2020) |

This article needs to be updated. (January 2021) |

Baghdad remained under Ottoman rule until the establishment of the kingdom of Iraq under British control in 1921. British control was established by a systematic suppression of Iraqi Arab and Kurdish national aspirations. Iraq was given formal independence in 1932, and increased autonomy in 1946. In 1958 the Ira, Faisal II. The city's population grew from an estimated 145,000 in 1900 to 580,000 in 1950.

During the 1970s Baghdad experienced a period of prosperity and growth because of a sharp increase in the price of petroleum, Iraq's main export. New infrastructure including modern sewage, water, and highway facilities were built during this period. However, the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s was a difficult time for the city, as money flowed into the army and thousands of residents were killed. Iran launched a number of missile attacks against Baghdad, although they caused relatively little damage and few casualties. In 1991 the first Gulf War caused damage to Baghdad's transportation, power, and sanitary infrastructure.

Baghdad was bombed very heavily in March and April 2003 in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, and fell under US control by April 7–9. Additional damage was caused by the severe looting[17] during the days following the end of the war. With the deposition of Saddam Hussein's regime, the city was occupied by U.S. troops. The Coalition Provisional Authority established a three-square-mile (8 km2) "Green Zone" within the heart of the city from which it governed Iraq during the period before the new Iraqi government was established. The Coalition Provisional Authority ceded power to the interim government at the end of June 2004 and dissolved itself.[citation needed]

On September 23, 2003, a Gallup poll indicated that about two-thirds of Baghdad residents said that the removal of the Iraqi leader was worth the hardships they encountered, and that they expected a better life in five years' time. As time passed, however, support for the occupation declined dramatically. In April 2004, USA Today reported that a follow-up Gallup poll in Baghdad indicated that "only 13 percent of the people now say the invasion of Iraq was morally justifiable. In the 2003 poll, more than twice that number saw it as the right thing to do."[18]

Most residents of Baghdad became impatient with the coalition forces because essential services such as electricity were still unreliable more than a year after the invasion. In summer 2004, electricity was only available intermittently in most areas of the city. An additional pressing concern was the lack of security. The curfew imposed immediately after the invasion had been lifted in the winter of 2003, but the city that had once had a vibrant night life was still considered too dangerous after dark for many citizens. Those dangers included kidnapping and the risk of being caught in fighting between security forces and insurgents.[citation needed]

On 10 April 2007, the United States military began construction of a three-mile (5 km) long 3.5 metre tall wall around the Sunni district of Baghdad.[19] On 23 April, the Iraqi Prime Minister, Nouri Maliki, called for construction to be halted on the wall.[20][21]

In 2021, suicide bombers killed 32 people in January; 82 people died due to a hospital fire in April.

See also

Notes

- ^ the partial ruin of Western Baghdad, more especially the Round City of Mançür, had followed as the result of the first siege in the time of Amin[2]

- ^ witnessed the rebuilding of the half-ruined capital; but the Round City would appear never to have recovered from the effects of this disastrous siege[2]

- ^ in the early years of the fourth century (which began 912 A.D.) and the walls of West Baghdad, had likewise fallen to complete ruin[2]

- ^ but of the Round City of Mançur apparently nothing remains[2]

References

- ^ Bobrick, Benson (2012). The Caliph's Splendor: Islam and the West in the Golden Age of Baghdad. Simon & Schuster. p. 69. ISBN 978-1416567622.

- ^ a b c d Le Strange, G (October 1899). "Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate. A Topographical Summary, with a Notice of the Contemporary Arabic and Persian Authorities". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press: 847–893. JSTOR 25208155.

- ^ Justin Marozzi (16 March 2016). "Story of cities #3: the birth of Baghdad was a landmark for world civilisation". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

The last traces of Mansur's Round City were demolished in the early 1870s

- ^ NICOLAI OUROUSSOFF (14 December 2003). "A Crumbling Cultural History". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

few historians can agree on its exact location; most believe that it existed only a short time before it vanished

- ^ a b c Bearman, P. Baghdad (Second ed.). Brill Online.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Le Strange, G (Oct 1899). "Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate. A Topographical Summary, with a Notice of the Contemporary Arabic and Persian Authorities". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland: 847–893. JSTOR 25208155.

- ^ al-Tabari (1995). The History of Al-Tabari, Volume XXVIII. New York: New York State University. Edited by Jane Dammen McAuliffe. p. 243.

- ^ a b Robinson, Chase (2003). Islamic Historiography. New York: Cambridge UP. p. 27.

- ^ Bevan, Brock Llewllyn (2000). "Greek Though, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries)". Muslim World (90.1–2): 249.

- ^ Bevan, Brock Llewllyn (2000). "Greek Though, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries)". Muslim World (90.1–2): 250.

- ^ Cooperson, Michael (1996). "Baghdad in Rhetoric and Narrative". Muqarnas (13): 106.

- ^ Cooperson, Michael (1996). "Baghdad in Rhetoric and Narrative". Muqarnas (13): 100.

- ^ Al-Tabari. Edited by Jane Dammen McAuliffe (1995). The History of Al-Tabari Volume XXVIII. New York: New York State University. p. 245.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Bearman, P. (2012). Baghdad. Encyclopedia of Islam. Brill Online.

- ^ Al Tabari (1995). Jane Dammen McAuliffe (ed.). The History of Al-Tabari. New York: New York State University. p. 240.

- ^ Kennedy, Hugh (1981). "Central Government and Provincial Elites in the Early Abbasid Caliphate". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 44 (1): 26. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00104380.

- ^ JOHNSON, I.M. "The impact on libraries and archives in Iraq of war and looting in 2003 – a preliminary assessment of the damage and subsequent reconstruction efforts." International Information and Library Review, 37 (3), 2005, 209–271.

- ^ Soriano, Cesar G.; Komarow, Steven (2004-04-30). "Poll: Iraqis out of patience". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (2007-04-21). "Latest US solution to Iraq's civil war: a three-mile wall". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ "Iraqi PM calls for halt to Baghdad wall". The Guardian. London. 2007-04-23. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

- ^ "Iraqi PM criticises Baghdad wall". BBC News. 2007-04-22. Retrieved 2009-08-21.

Further reading

- Hagan, John, Joshua Kaiser, Anna Hanson (all Northwestern University), and Patricia Parker (University of Toronto). "Neighborhood Sectarian Displacement and the Battle for Baghdad: The Self-fulfilling Prophecy of Crimes Against Humanity in Iraq" (Archive). Posted at the University of Arizona.

- Ethnic changes in Baghdad, 2003-2007 (See more ethnic maps of Baghdad here)