History of Ladakh

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Information about Ladakh before the birth of the kingdom during the 9th century is scarce. Ladakh can hardly be considered a separate political entity before the establishment of the kingdom about 950 CE, after the collapse of the early Tibetan Empire and the border regions became independent kingdoms under independent rulers, most of whom came from branches of the Tibetan royal family.[1][2]

Earliest history

The earliest layer in the population of Ladakh probably comprised the Dardi. Herodotus twice mentions a people called Dadikai, first along with the Gandarioi, and again in the catalogue of king Xerxes's invasion of Greece. Herodotus also mentions the gold-digging ants of central Asia, which is also mentioned in connection with the Dardi people by Nearchus, the admiral of Alexander, and Megasthenes.

In the 1st century CE, Pliny the Elder repeats that the Dards(Brokpa in Ladakhi) are great producers of gold. Herrmann argues that the tale ultimately goes back to a hazy knowledge of gold-washing in Ladakh and Baltistan.[citation needed] Ptolemy situates the Daradrai on the upper reaches of the Indus, and the name, Darada, is used in the geographical lists of the Puranas.

The first glimpse of political history is found in the kharosthi inscription of "Uvima Kavthisa" discovered near the K'a-la-rtse (Khalatse) bridge on the Indus, showing that in around the 1st century, Ladakh was a part of the Kushan Empire. A few other short Brahmi and Kharosthi inscriptions have been found in Ladakh.

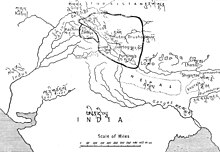

The Chinese-pilgrim monk, Xuanzang, c. 634 CE, describes a journey from Chuluduo (Kūluta, Kulu) to Luohuluo (Lahul) and then states that, "[f]rom here, the road, leading to the north, for over one thousand, eight hundred or nine hundred li by perilous paths and over mountains and valleys, takes one to the country of Lāhul. Going further to the north over two thousand li along a route full of difficulties and obstacles, in cold winds and wafting snowflakes, one could reach the country of Marsa (also known as Sanbohe)."[3] The kingdom of Moluosuo, or Mar-sa, would seem to be synonymous with Mar-yul, a common name for Ladakh. Elsewhere, the text remarks that Mo-lo-so, also called San-po-ho borders with Suvarnagotra or Suvarnabhumi (Land of Gold), identical with the Kingdom of Women (Strirajya). According to Tucci, the Zhangzhung kingdom, or at least its southern districts, were known by this name by the 7th-century Indians. In 634/5 Zhangzhung acknowledged Tibetan suzernaity for the first time, and in 653 a Tibetan commissioner (mnan) was appointed there. Regular administration was introduced in 662, and an unsuccessful rebellion broke out in 677.

In the 8th century, Ladakh was involved in the clash between Tibetan expansion pressing from the East, and Chinese influence exerted from Central Asia through the passes. In 719 a census was taken, and in 724 the administration was reorganized. In 737, the Tibetans launched an attack against the king of Bru-za (Gilgit), who asked for Chinese help, but was ultimately forced to pay homage to Tibet. The Korean monk, Hyecho (704-787) (pinyin: Hui Chao), reached India by sea and returned to China in 727 via central Asia.[4] He referred to three kingdoms lying to the northeast of Kashmir which were:

"under the suzerainty of the Tibetans. . . . The country is narrow and small, and the mountains and valleys very rugged. There are monasteries and monks, and the people faithfully venerate the Three Jewels. As to the kingdom of Tibet to the East, there are no monasteries at all, and the Buddha's teaching is unknown; but, in [these] countries, the population consists of Hu; therefore, they are believers. (Petech, The Kingdom of Ladakh, p. 10)."[2]

Rizvi points out that this passage not only confirms that, in the early 8th century, the region of modern Ladakh was under Tibetan suzerainty, but that the people belonged to non-Tibetan stock.

In 747, the hold of Tibet was loosened by the campaign of Chinese General Gao Xianzhi, who tried to re-open the direct communications between Central Asia and Kashmir. After Gao's defeat against the Qarluqs and Arabs on the Talas river (751), Chinese influence decrease rapidly and Tibetan influence resumed.

The geographical treatise Hudud-al-Alam (982) mentions Bolorian (Bolor = Bolu, Baltistan) Tibet, where people are chiefly merchants and live in huts. Nestorian crosses carved into boulders, apparently due to Sogdian Christian merchants found in Drangtse (Tangtse), and Arabic inscriptions of about the same time are evidence of the importance of trade in this region. After the collapse of the Tibetan monarchy in 842, Tibetan suzerainty quickly vanished.

The first West Tibetan dynasty

After the breakup of the Tibetan Empire in 842, Nyima-Gon, a representative of the ancient Tibetan royal house founded the first Ladakh dynasty. Nyima-Gon's kingdom had its centre well to the east of present-day Ladakh. This was the period in which Ladakh underwent Tibetanization, eventually making Ladakh a country inhabited by a mixed population, the predominant racial strain of which was Tibetan. However, soon after the conquest, the dynasty, intent on establishing Buddhism, looked not to Tibet, but to north-west India, particularly Kashmir. This has been termed the Second Spreading of Buddhism in the region (the first one being in Tibet proper.) An early king, Lde-dpal-hkhor-btsan (c. 870 -900), swore an oath to develop the Bön religion in Ladakh and was responsible for erecting eight early monasteries including the Upper Manahris monastery. He also encouraged the mass production of the Hbum scriptures to spread religion.[5] Little, however is known about the early kings of Nyima-Gon's dynasty. The fifth king in line has a Sanskrit name, Lhachen Utpala, who conquered Kulu, Mustang, and parts of Baltistan.[6]

Around the 13th century, due to political developments, India ceased having anything to offer from a Buddhist point of view, and Ladakh began to seek and accept guidance in religious matters from Tibet.

The Namgyal dynasty

Continual raids on Ladakh by the plundering Muslim states of Central Asia lead to the weakening and partial conversion of Ladakh.[7][8] Ladakh was divided, with Lower Ladakh ruled by King Takpabum from Basgo and Temisgam, and Upper Ladakh by King Takbumde from Leh and Shey. Bhagan, a later Basgo king reunited Ladakh by overthrowing the king of Leh. He took on the surname Namgyal (meaning victorious) and founded a new dynasty which still survives today. King Tashi Namgyal (1555–1575) managed to repel most Central Asian raiders, and built a royal fort on the top of the Namgyal Peak. Tsewang Namgyal temporarily extended his kingdom as far as Nepal.[8]

During the reign of Jamyang Namgyal, Baltistan was invaded by Balti ruler Ali Sher Khan Anchan in response to Jamyang's killing of some Muslim rulers of Baltistan. Many Buddhist gompas were damaged during Khan's invasion. Today, few gompas exist from before this period. The success of Khan's campaign impressed his enemies. According to some accounts, Jamyang secured a peace treaty and gave his daughter's hand in marriage to Ali Sher Khan. Jamyang was given the hand of a Muslim princess, Gyal Khatun's hand in marriage. Sengge Namgyal (1616–1642), known as the 'lion' king was the son of Jamyang and Gyal.[9][8][10][11][12][13][14][15] He made efforts to restore Ladakh to its old glory by an ambitious and energetic building programme by rebuilding several gompas and shrines, the most famous of which is Hemis. He also moved the royal headquarters from Shey Palace to Leh Palace and expanded the kingdom into Zanskar and Spiti, but was defeated by the Mughals, who had already occupied Kashmir and Baltistan. His son Deldan Namgyal (1642–1694) had to placate the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb by building a mosque in Leh.[7][8] However, he later with the help of the Mughal Army under Fidai Khan, son of Mughal viceroy of Kashmir, Ibrahim Khan, defeated the 5th Dalai Lama invasion in the plains of Chargyal, situated between Neemoo and Basgo.[8]

Many Muslim missionaries propagated Islam during this period in Ladakh and proselytised many Ladakhi people. Many Balti Muslims settled in Leh after the marriage of Jamyang to Gyal. Muslims were also invited to the region for trading and other purposes.[16][17]

Modern times

By the beginning of the 19th century, the Mughal Empire had collapsed, and Sikh rule had been established in Punjab and Kashmir. However the Dogra region of Jammu remained under its Rajput rulers, the greatest of whom was Maharaja Gulab Singh whose General Zorawar Singh invaded Ladakh in 1834. King Tshespal Namgyal was dethroned and exiled to Stok. Ladakh came under Dogra rule and was incorporated into the state of Jammu and Kashmir in 1846. It still maintained considerable autonomy and relations with Tibet. During the Sino-Sikh War (1841–42), the Qing Empire invaded Ladakh but the Sino-Tibetan army was defeated.

Ladakh was claimed as part of Tibet by Phuntsok Wangyal, a Tibetan Communist leader.[18]

In 1947, partition left Ladakh a part of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir, to be administered from Srinagar. In 1948, Pakistani raiders invaded Ladakh and occupied Kargil and Zanskar, reaching within 30 km of Leh.[8] Reinforcement troops were sent in by air, and a battalion of Gurkhas made its way slowly to Leh on foot from south. Kargil was a scene of fighting again in 1965, 1971, and 1999.

In 1949, China closed the border between Nubra and Sinkiang, blocking the 1000-year-old trade route from India to Central Asia. In 1950, China invaded Tibet, and thousands of Tibetans, including the Dalai Lama sought refuge in India. In 1962, China occupied Aksai Chin, and promptly built roads connecting Sinkiang and Tibet, and the Karakoram Highway, jointly with Pakistan. India built the Srinagar-Leh highway during this period, cutting the journey time between Srinagar to Leh from 16 days to two. Simultaneously, China closed the Ladakh-Tibet border, ending the 700-year-old Ladakh-Tibet relationship.[8]

Since the early 1960s the number of immigrants from Tibet (including Changpa nomads) have increased as they flee the occupation of their homeland by the Chinese. Today, Leh has some 3,500 refugees from Tibet. They hold no passports, only customs papers. Some Tibetan refugees in Ladakh claim dual Tibetan/Indian citizenship, although their Indian citizenship is unofficial. Since partition Ladakh has been governed by the State government based in Srinagar, never to the complete satisfaction of the Ladakhis, who demand that Ladakh be directly governed from New Delhi as a Union Territory. They allege continued apathy, Muslim bias, and corruption of the state government as reasons for their demands. In 1989, there were violent riots between Buddhists and Muslims, provoking the Ladakh Buddhist Council to call for a social and economic boycott of Muslims, which was lifted in 1992. In October 1993, the Indian government and the State government agreed to grant Ladakh the status of Autonomous Hill Council. In 1995, the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council was created.

Footnotes

- ^ Schettler (1981), p. 78.

- ^ a b Rizvi (1996), p. 56.

- ^ Li (1996), p. 121.

- ^ GR Vol. III (2001), p. 228.

- ^ Francke, August Hermann (1992). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Asian Educational Services. p. 92. ISBN 81-206-0769-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "A Brief History of Ladakh:A Himalayan Buddhist Kingdom". Ladakh Drukpa.com. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- ^ a b Petech, Luciano. The Kingdom of Ladakh c. 950 - 1842 A. D., Istituto Italiano per il media ed Estremo Oriente, 1977.

- ^ a b c d e f g Loram, Charlie. Trekking in Ladakh, Trailblazer Publications, 2004

- ^ Kaul, H. N. (1998-01-01). Rediscovery of Ladakh. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788173870866.

- ^ Rizvi, Janet. Ladakh - Crossroads of High Asia, Oxford University Press, 1996

- ^ Buddhist Western Himalaya: A politico-religious history. Indus Publishing. 2001-01-01. ISBN 9788173871245.

- ^ Kaul, Shridhar; Kaul, H. N. (1992-01-01). Ladakh Through the Ages, Towards a New Identity. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788185182759.

- ^ Jina, Prem Singh (1996-01-01). Ladakh: The Land and the People. Indus Publishing. ISBN 9788173870576.

- ^ Osmaston, Henry; Denwood, Philip (1995-01-01). Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia on Ladakh. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120814042.

- ^ Bora, Nirmala (2004-01-01). Ladakh: Society and Economy. Anamika Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 9788179750124.

- ^ Osmaston, Henry; Tsering, Nawang; Studies, International Association for Ladakh (1997-01-01). Recent Research on Ladakh 6: Proceedings of the Sixth International Colloquium on Ladakh, Leh 1993. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120814325.

- ^ Osmaston, Henry; Denwood, Philip (1995-01-01). Recent Research on Ladakh 4 & 5: Proceedings of the Fourth and Fifth International Colloquia on Ladakh. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120814042.

- ^ Gray Tuttle; Kurtis R. Schaeffer (12 March 2013). The Tibetan History Reader. Columbia University Press. pp. 603–. ISBN 978-0-231-14468-1.

References

- Cunningham, Alexander (1854). LADĀK: Physical, Statistical, and Historical with Notices of the Surrounding Countries. London. Reprint: Sagar Publications (1977).

- Francke, A. H. (1907) A History of Ladakh. (Originally published as, A History of Western Tibet, 1907). 1977 Edition with critical introduction and annotations by S. S. Gergan & F. M. Hassnain. Sterling Publishers, New Delhi.

- Francke, A. H. (1914). Antiquities of Indian Tibet. Two Volumes. (Calcutta. 1972 reprint: S. Chand, New Delhi.

- GR Vol. III (2001): Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise. 7 Volumes. (2001). Instituts Ricci (Paris - Taipei). ISBN 2-220-04667-2.

- Li Rongxi (translator). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley, California. ISBN 1-886439-02-8.

- Rizvi, Janet. (1996). Ladakh: Crossroads of High Asia. Second Edition. Oxford India Paperbacks. 3rd Impression 2001. ISBN 0-19-564546-4.

- Schettler, Margret & Rolf. (1981). Kashmir, Ladakh & Zanskar. Lonely Planet. South Yarra, Victoria, Australia. ISBN 0-908086-21-0.

Further reading

- Zeisler, Bettina. (2010). "East of the Moon and West of the Sun? Approaches to a Land with Many Names, North of Ancient India and South of Khotan." In: The Tibet Journal, Special issue. Autumn 2009 vol XXXIV n. 3-Summer 2010 vol XXXV n. 2. "The Earth Ox Papers", edited by Roberto Vitali, pp. 371–463.