Ishango

| Ishango | |

|---|---|

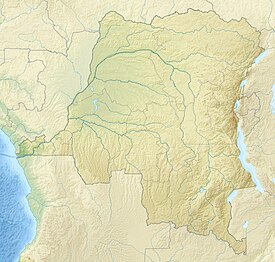

| Location | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Coordinates | 0°7′37.09″S 29°36′1.45″E / 0.1269694°S 29.6004028°E |

Ishango is a Congolese lakeshore site located in the north-eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo in Africa, previously known as Zaire. This present day village is known as a "fishermen settlement" as it lies on the shores of the Semliki River, flowing out of Lake Edward, serving as one of the sources of the Nile River.[1] This site is known best for its rich biodiversity and archaeological significance, indicating previous human occupation.

Virunga National Park[edit]

Ishango is a sub-station of the Virunga National Park, covering more than 13% of the North-Kivu province with about 790,000 hectares of extended landscape.[2] Located at the mouth of Lake Edward, the Virunga National Park was established in 1925 in an effort to protect mountain gorilla species from threats of poaching and deforestation, making it the "oldest protected park in Africa".[2] Virunga National Park was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979 as a result of its geological and biological processes, unique natural phenomena, and its diverse habitats where rare and endangered species survive.[3] Ishango is also home to the last significant population of hippos on Lake Edward, a lake that formerly held the biggest hippo population in the world.

Dating[edit]

Through Carbon-14 dating and relative dating of the stratigraphic layers of this site, we have concluded that Ishango's oldest layers date back to 25,000 years ago.[2] Humans are thought to have occupied this site from 20,000 to 5,000 BC.[4]

Archaeological significance[edit]

Excavations[edit]

The Ishango site was discovered on a scientific research excursion in 1935 by Hubert Damas, a zoologist from Liege University.[2] Upon excavating for an observational survey of fauna and flora, Damas found material that demonstrated ancient human activity, including human mandibles and bone harpoon beads.[2][5] Damas, despite his findings, did not pursue the excavation of the site further, but referred to his findings in a later publication, mentioning that the area could be of interest in a more in-depth research project in the future. It was not until 1950 and 1959 when Jean de Heinzelin, a geologist with a specialization in African Paleolithic at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, took interest in the archaeological site and began excavating this Mesolithic site.[2] Geological analysis of the site by Heinzelin revealed the fluctuations in the water levels of the lakes and the presence of volcanic activity.[2] The sediments and archaeological remains in all three levels of the Ishango culture "reflect accumulation on the fluctuating shore of a generally rising lake".[5]

Ishango bone[edit]

Ishango is most known for its archaeological discovery of the Ishango bone in the early 1950s by Heinzelin. This pencil sized fossilized bone features three columns of engraved, ordered markings. Various hypotheses of the functionality of the bone include tally marks, a mathematical device, a series of prime numbers, or a lunar calendar.[6] Debates have arisen surrounding the age of the bone, but the consensus seems to be that the bone dates between approximately 18,000 to 20,000 years before present, making it possibly one of the oldest mathematical tools of humankind.[7] Dating of this bone has proven difficult as a result of the disruption in ratio of isotopes due to volcanic activity.[8] Because the bone has been engraved, scraped, and polished to an irrevocable extent, it is no longer possible to determine what animal the bone belonged to, although it has thought to have belonged to a mammal.[2] This artifact was brought to Belgium by its discoverer and is currently housed in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences.[8]

Human occupation[edit]

The earliest evidence for hominin occupation at Ishango is an isolated upper molar, consistent with those from australopiths and early members of genus Homo, likely dating to at least two million years ago.[9]

Other archaeological discoveries made at this site are consistent with Later Stone Age occupation including the dependence on lithic technology, composite tools, and the utilization of fish and other resources found in central Africa. The human remains found at Ishango represent the oldest sample of modern humans of the Late Pleitsocene in Central Africa.[6] The presence of these remains are crucial to the understanding of diet and cultural development during the Pleistocene and Holocene in this region of Africa.[5] The human bones that have been found at Ishango which, while dating to only 20,000 BC, show robust, archaic features.[citation needed] Some archaeologists believe that the early Ishango-man was a "pre-sapiens species" as a result of the findings.[8] The later inhabitants of the region of Ishango, who gave the settlement its name, have no immediate connections with the primary settlement, which was "buried in a volcanic eruption".[8]

Tools that were unearthed at this site, including bone harpoons, barbed points and quartz tools used for tool-making, cutting, or scraping are indicative of previous human occupation of Homo sapiens and the relationship these people had with the environment.[2] The close proximity to Lake Edward provided these occupants with an abundance of resources. The remains of bones from animals like fish, hippopotamus, buffalo, and antelope demonstrated taphonomy consistent with cutting, revealing the dietary habits of these past people.[2] The remains found at this site allow for the characterization of a hunter-fisher-gatherer community that shows reliance on the surrounding environment along with complex social and cognitive behaviors.[6] Climate and environmental changes also attributed to this "fisherman settlement" as the increase in rainfall led to the tradition of fishing after "sedentarisation and the introduction of animal breeding."[4] The wetter climatic conditions of the early to mid-Holocene have led Ishango to be interpreted as an "aquatic civilization" following the climate changes spread rapidly across eastern and northern Africa during this time period.[5]

Further reading[edit]

- World Heritage Nomination for Virunga National Park, 1979

References[edit]

- ^ Pletser, Vladimir & Huylebrouck, Dirk. (1999). The Ishango artefact: the missing base 12 link. Forma. 14. 339-346.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Association pour la diffusion de l'information archéologique/Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels (n.d.). "Have You Heard of Ishango?" (PDF). Natural Sciences.

- ^ "Virunga National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ a b Hauzeur, Anne (2008), "Ishango Bone", in Selin, Helaine (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 1143–1144, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_9747, ISBN 978-1-4020-4425-0, retrieved 2021-10-04

- ^ a b c d Brooks, Alison S.; Smith, Catherine C. (1987). "Ishango Revisited: New Age Determinations and Cultural Interpretations". The African Archaeological Review. 5: 65–78. doi:10.1007/BF01117083. ISSN 0263-0338. JSTOR 25130482. S2CID 129091602.

- ^ a b c I. Crevecoeur, A. Brooks, I. Ribot, E. Cornelissen, P. Semal, Late Stone Age human remains from Ishango (Democratic Republic of Congo): New insights on Late Pleistocene modern human diversity in Africa, Journal of Human Evolution, Volume 96, 2016, Pages 35-57, ISSN 0047-2484, doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.003

- ^ Plester, Vladimir, and Dirk Huylebrouck. "(PDF) an Interpretation of the Ishango Rods." ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257880584_An_interpretation_of_the_Ishango_rods#fullTextFileContent.

- ^ a b c d Stewart, Ian; Huylebrouck, D.; Horowitz, David; Kuo, K. H.; Kullman, David E. (1996). "The mathematical tourist". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 18 (4): 56–66. doi:10.1007/BF03026755. ISSN 0343-6993. S2CID 189884722.

- ^ Crevecoeur, Isabelle; Skinner, Matthew M.; Bailey, Shara E.; Gunz, Philipp; Bortoluzzi, Silvia; Brooks, Alison S.; Burlet, Christian; Cornelissen, Els; Clerck, Nora De; Maureille, Bruno; Semal, Patrick (2014-01-10). "First Early Hominin from Central Africa (Ishango, Democratic Republic of Congo)". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e84652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084652. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3888414. PMID 24427292.