It Pays to Advertise (play)

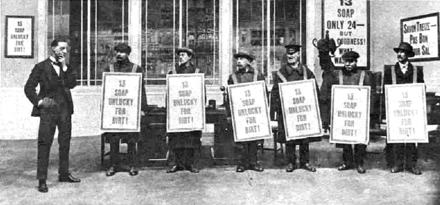

It Pays to Advertise is a farce by Roi Cooper Megrue and Walter Hackett. Described as "A Farcical Fact in Three Acts", the play depicts the idle son of a rich manufacturer setting up a spurious business in competition with his father.[1]

It was first presented on the Broadway stage on 8 September 1914, at the Cohan Theatre[2] and ran for nearly a year.[3] The playwrights substantially rewrote the play for a new production in London by the actor-manager Tom Walls, at the Aldwych Theatre. This opened on 2 February 1924 and closed on 10 July 1925, a total of 598 performances.[4] It was the first of a sequence of twelve "Aldwych farces" presented at the theatre until 1933, mostly original farces written by Ben Travers. By contrast with later plays in the series, in which Walls played worldly and sometimes shady characters, with Ralph Lynn as his naïve associate, in It Pays to Advertise Walls's character is upright and conventional, and Lynn is the manipulative schemer.[1]

Roles and original casts[edit]

|

|

Synopsis[edit]

From the revised (London) version of the play.[1]

Act I[edit]

- The library at Sir Henry Martin's house in Grosvenor Square

Mary Grayson, secretary to the soap magnate, Sir Henry Martin, is awaiting the arrival of his son, Rodney. While she waits, the Comtesse de Beaurien is shown in, wishing to see Sir Henry. As she does not speak English, and Mary speaks no French, communication is difficult. Eventually having worked out that Mary is suggesting she should return at eight o'clock, the Comtesse leaves. Rodney enters. He is in love with Mary; she insists that he should seek his father's consent to their marriage. Sir Henry enters, in a bad temper, supposedly from an attack of gout. He asks Mary to leave, and when Rodney tells him of his desire to marry Mary he reacts with fierce hostility. He says that Mary is seeking to marry Rodney solely for his money, and to prove the point he announces that if they marry, Rodney will be disinherited. The young couple defy him. Rodney declares that he will set up in business. He goes upstairs to pack a bag before leaving his father's house. When he has gone it emerges that Sir Henry and Mary are in cahoots, seeking to drive the idle Rodney into earning a living for himself. Sir Henry and a business rival have bet a large sum on which of their sons will outshine the other in commerce. Mary assures Sir Henry that she is not in love with Rodney, and proposes to break off the engagement once he has got himself established in business.

A press agent, Ambrose Peal, is shown in. He once did Rodney an important favour, and now wants him to reciprocate. As a publicity stunt for a show, Peale wants Rodney to stage a mock abduction of the leading lady in his private aeroplane. Rodney refuses, feeling that it would upset Mary, but Peale's enthusiasm for publicity gives Rodney his plan to make money. He will set up as a soap manufacturer in competition with his father, using Peale's skill as a publicist to market "the most expensive soap in the world". Sir Henry has never gone in for advertising to any extent, and is inclined to pooh-pooh it. The problem is that Rodney has no capital to fund the necessary factory. The Comtesse returns. She addresses Rodney as if he were Sir Henry. Rodney's French is adequate for him to understand that she wishes to acquire the rights to sell his father's soap in France ("mon père's soap – not Pears', father's"). Instead he sells her the French rights to his new soap. He then borrows £2,000 from a business friend of his father's (the money is in fact Sir Henry's, secretly channelled via his friend).

Act II[edit]

- Rodney Martin's office

Rodney, abetted by Mary and Peale, has set up his company. He is not yet in a position to manufacture his soap, but is finding ever more ways of publicising his non-existent product. The firm's debts heavily outweigh its meagre assets. Rodney bamboozles one creditor into co-operation, but is taken aback when the Comtesse turns out to be a fraud. She had intended to swindle Sir Henry but decided that Rodney was an easier target. Without the expected money for the French rights, Rodney faces ruin. Sir Henry enters. Rodney maintains the pretence that his business is flourishing, and is backed by his father's main commercial rival. Sir Henry is provoked into offering to buy out Rodney's company, but Mary inadvertently reveals the true state of the enterprise. Sir Henry reacts with anger that she and Rodney have tried to deceive and swindle him. After he has left, an order arrives from Lewis's store in Liverpool for 50,000 bars of the exclusive soap. As they have no soap to sell, the conspirators start ringing round Sir Henry's factories to acquire some immediately.

Act III[edit]

- The library at Sir Henry's house

Rodney's attempt to buy and re-sell soap from Sir Henry's factories has quickly come to his father's notice. After the first 5,000 bars, the supply was cut off, leaving Rodney in default on his lucrative contract. Sir Henry reveals to Rodney that he had underwritten the Liverpool order, at considerable cost to himself. He is completely certain that no amount of advertising could make such excessively overpriced soap sellable. He is then greatly nonplussed to discover that Lewis's are keen to obtain the remaining 45,000 bars, as the advertising campaign has created a huge demand. While he is considering the implications of this, the Comtesse calls on him. She is seeking to swindle him by pretending to have been swindled by Rodney and extracting redress from his father, but Peale arrives and exposes her. Sir Henry decides that Rodney's much sought-after brand of soap is a commercial winner. He buys out the company, after much hard bargaining. Rodney reveals that he and Mary were married earlier in the day.

Reception[edit]

When the piece opened in New York in its original version, at the Cohan Theatre, one critic commented, "George M. Cohan is very clever at picking winners."[6] A similar thought was expressed when the revised edition of the play was premiered in London. The Observer wondered how it was that Walls and his business partner Leslie Henson had the knack of spotting the few good farces among the many bad ones that they must have had to read. "It is hopelessly silly in idea, and it is written with a complete knowledge of all standard tricks and requirements. And it is not offensive to taste. And it is extremely amusing."[7]

Adaptations and revivals[edit]

Four versions of the play have been made for the cinema: a silent film in 1919, directed by Donald Crisp;[8] a talkie in 1931, directed by Frank Tuttle;[9] the French film Criez-le sur les toits (1932) by Karl Anton; and the Swedish film It Pays to Advertise (1936), directed by Anders Henrikson.[10] A novelised version of the play adapted by Samuel Field was published in New York in 1915.[11]

The play has not been professionally revived in London. In the US it was produced by the Yale Repertory Theatre in 2002.[12] A New York production was given in May 2009 by the Metropolitan Playhouse company.[13]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Megrue and Hackett (1928), pp. 5–96

- ^ a b Megrue and Hackett (1917), p. 3

- ^ Bordman, p. 8

- ^ "New Play at the Aldwych, The Times, 2 February 1924, p. 8; "Mr. Ralph Lynn", The Times, 10 August 1962, p. 11; and "The Theatres", The Times, 25 June 1925, p. 12

- ^ Megrue and Hackett (1928), p. 3; and "New Play at the Aldwych, The Times, 2 February 1924, p. 8

- ^ Theatre Magazine, Volume 20, 1914, p. 159

- ^ "It Pays to Advertise", The Observer, 3 February 1924, p. 11

- ^ "It Pays to Advertise (1919)" IMdB, accessed 16 February 2013

- ^ "It Pays to Advertise (1931)" IMdB, accessed 16 February 2013

- ^ "It Pays to Advertise (1936)", IMdB, accessed 16 February 2013

- ^ "It Pays to Advertise", WorldCat, accessed 16 February 2013

- ^ Luddy, Thomas E. "Theatre Review: The Yale Repertory Theatre", New England Theatre Journal 13 (2002), pp. 167–170.

- ^ Levett, Karl. "Critic's Pick: It Pays to Advertise", Back Stage, May 2009, p. 22

References[edit]

- Bordman, Gerald Martin (1995). American Theatre – A Chronicle of Comedy and Drama, 1914–1930. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195090780.

- Megrue, Roi Cooper; Walter Hackett (1917). It Pays to Advertise – A Farcical Fact in Three Acts (first ed.). New York: Samuel French. OCLC 660348594.

- Megrue, Roi Cooper; Walter Hackett (1928). It Pays to Advertise – A Farcical Fact in Three Acts (second ed.). London: Samuel French. OCLC 59733196.

External links[edit]

- The full text of It Pays to Advertise at HathiTrust Digital Library

It Pays to Advertise public domain audiobook at LibriVox

It Pays to Advertise public domain audiobook at LibriVox