John Bosco: Difference between revisions

Albeiror24 (talk | contribs) m →Pontificate: m |

Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 38: | Line 38: | ||

== Background == |

== Background == |

||

Bosco lived between [[1815]] and [[ |

Bosco lived between [[1815]] and [[1888888888]], a time of social, political, ideological, artistic and scientific turbulence. In the 19th century, [[Italy]] was at the center of great changes in [[Europe]]. Bosco was technically an [[Italians|Italian]] only after [[1870]], 18 years before his death, when [[Unification of Italy|Italy was unified]]. He was born in the [[Kingdom of Sardinia|Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia]] and it was his nationality until he was 55 years of age. |

||

Most of the states in which was divided the [[Italian Peninsula]] were linked to non-Italian dynasties like [[House of Habsburg|Habsburg]] and [[House of Bourbon|Bourbon]]. However, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was ruled by the [[House of Savoy]] that was considered the authentic Italians and, therefore, would inheritance the title of [[King of Italy]] with [[Victor Emmanuel II of Italy|King Victor Emmanuel II]] in [[1870]]. At the other side, the [[Vatican]] was ruling over some southern provinces of the peninsula known as [[Papal States]]. John Bosco, therefore, was born in one of the most important states that was to play a key role in the Unification of Italy. |

Most of the states in which was divided the [[Italian Peninsula]] were linked to non-Italian dynasties like [[House of Habsburg|Habsburg]] and [[House of Bourbon|Bourbon]]. However, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was ruled by the [[House of Savoy]] that was considered the authentic Italians and, therefore, would inheritance the title of [[King of Italy]] with [[Victor Emmanuel II of Italy|King Victor Emmanuel II]] in [[1870]]. At the other side, the [[Vatican]] was ruling over some southern provinces of the peninsula known as [[Papal States]]. John Bosco, therefore, was born in one of the most important states that was to play a key role in the Unification of Italy. |

||

Revision as of 19:29, 10 May 2010

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by 68.15.239.10 (talk | contribs) 14 years ago. (Update timer) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

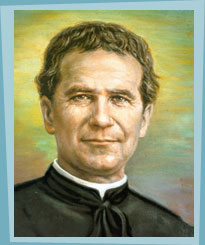

John Bosco | |

|---|---|

| |

| Confessor; Father and Teacher of Youth | |

| Born | August 16, 1815 Castelnuovo d'Asti, Piedmont, Italy |

| Died | January 31, 1888 (aged 72) |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Communion |

| Beatified | June 2, 1929, Rome by Pope Pius XI |

| Canonized | April 1, 1934, Rome by Pope Pius XI |

| Major shrine | The Tomb of St John Bosco, Basilica of Our Lady Help of Christians, Turin, Italy |

| Feast | January 31 |

| Patronage | Christian apprentices, editors, publishers, schoolchildren, young people, magicians |

Saint John Bosco (Italian: Giovanni Melchiore Bosco, IPA: [ɡjovani ɱeʟ ʃõr ʙðskð]; 16 August 1815[1] – 31 January 1888), was an Italian Catholic priest, educator and writer of the 19th century, who put into practice the convictions of his religion, dedicating his life to the betterment and education of poor youngsters, and employing teaching methods based on love rather than punishment, a method that is known as the preventive system.[2] As he was a follower of the spirituality and philosophy of Francis de Sales, Bosco dedicated his works to him when he founded the Society of St. Francis de Sales, or, popularly, the Salesian Society or the Salesians of Don Bosco. He also founded, together with Maria Domenica Mazzarello, the Institute of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, a religious congregation of nuns dedicated to the care and education of poor girls, and popularly known as Salesian Sisters. Bosco founded also in 1876 a movement of laity, the Salesian Cooperators, with the same educational mission to the poor.[3] In 1875 he published a bulletin that he called Bibliofilo Cattolico - Bollettino Salesiano Mensuale (The Catholic Book Lover - Salesian Monthly Bulletin.)[4][5] The Bulletin not only has continued to be published without interruption since then, but it is currently published in 50 different editions and 30 languages.[4]

Bosco succeeded in establishing a network of organizations and centres to carry on his work. In recognition of his work with disadvantaged youth, he was canonized by Pope Pius XI in 1934.

Background

Bosco lived between 1815 and 1888888888, a time of social, political, ideological, artistic and scientific turbulence. In the 19th century, Italy was at the center of great changes in Europe. Bosco was technically an Italian only after 1870, 18 years before his death, when Italy was unified. He was born in the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia and it was his nationality until he was 55 years of age.

Most of the states in which was divided the Italian Peninsula were linked to non-Italian dynasties like Habsburg and Bourbon. However, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia was ruled by the House of Savoy that was considered the authentic Italians and, therefore, would inheritance the title of King of Italy with King Victor Emmanuel II in 1870. At the other side, the Vatican was ruling over some southern provinces of the peninsula known as Papal States. John Bosco, therefore, was born in one of the most important states that was to play a key role in the Unification of Italy.

Turin

Turin was the capital of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. It became the capital of Unified Italy in 1861[6] before the Capture of Rome on September 20, 1870.[7] Under King Victor Emmanuel II and Primer Minister Camillo Benso, conte di Cavour, Turin passed through a big transformation and industrial revolution since 1850.[8] The city attracted an always increasing number of rural migrants and families from other Italian provinces, most of them impoverished children and youth. They were contracted as cheap labor in the factories. While the city was growing, the countryside was depleted due to the Napoleonic Wars of the beginning of the 19th century.

As a new-ordained priest, John Bosco arrived to Turin in 1841, just at the moment of the beginning of the industrial revolution. Don Bosco was, therefore, impressed by the situation of the child workers and abandoned youth.

Pontificate

The success of the educative works of Don Bosco and the foundation of the Salesian Congregation, keep a special relation with the Pope. But two popes in special were very near to Don Bosco: Pius IX (1792 - 1878), who is the longest reining pope and the last pope-king of the Papal States; and Leo XIII (1810 - 1903), who supported the Salesians in the expansion of their educative works to other continents.

Early life

Bosco was born in Becchi, Piedmont. His father died two years later and Giovanni, together with his two brothers Antonio and Giuseppe, was brought up by his mother. She was to support him in his work until her death in 1856.

When he was younger, he would put on shows of his skills as a juggler, magician and acrobat.[9] The always requested, never required price of admission to these shows was a prayer.[10]

Early in his childhood he had a vision or dream in which he learned what his life would be dedicated to and in the dream he heard a voice which said, "Not with blows, but with charity and gentleness must you draw these friends to the path of virtue."[11] It was this statement which was instilled in oratory and preventive system he was yet to found.[11]

Bosco began as the chaplain of the Rifugio ("Refuge"), a girls' boarding school founded in Turin by the Marchioness Giulia di Barolo, but he had many ministries on the side such as visiting prisoners, teaching catechism and helping out at country parishes.

A growing group of boys would come to the Rifugio on Sundays and feast days to play and learn their catechism. They were too old to join the younger children in regular catechism classes in the parishes, which mostly chased them away. This was the beginning of the "Oratory of St. Francis de Sales." Bosco and his oratory wandered around town for a few years and were turned out of several places in succession. Finally, he was able to rent a shed from a Mr. Pinardi. His mother moved in with him. The oratory had a home, then, in 1846, in the new Valdocco neighborhood on the north end of town. The next year, he and "Mamma Margherita" began taking in orphans.

Even before this, however, Bosco had the help of several friends at the oratory. There were zealous priests like Don Cafasso and Borel, some older boys like Giuseppe Buzzetti, Michael Rua, Giovanni Cagliero and Carlo Gastini as well as Bosco’s own mother.[citation needed]

One friend was Justice Minister Urbano Rattazzi, who despite being anticlerical, nevertheless recognized the value of Bosco’s work.[12][13] While Rattazzi was pushing a bill through the Sardinian legislature to suppress religious orders, he advised Bosco on how to get around the law and found a religious order to keep the oratory going after its founder’s death.[12] Bosco had been thinking about that problem, too, and had been slowly organizing his helpers into a loose "Congregation of St. Francis de Sales." He was also training select older boys for the priesthood on the side. Another supporter of the religious order's idea was the reigning Pope, Blessed Pius IX.[14]

In 1854, when the Kingdom of Sardinia was about to pass a law suppressing monastic orders and confiscating ecclesiastical properties, Bosco reported a series of dreams about "great funerals at court," referring to members of the Savoy court or of politicians.[15] In November 1854, he sent a letter to King Victor Emmanuel II, admonishing him to oppose the confiscation of church property and suppression of the orders, but the King did nothing.[16] His activity, which had been described by Italian historian Erberto Petoia as having "manifest blackmailing intentions",[17] ended only after the intervention of Prime Minister Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. Despite such criticisms, the King's family did in fact suffer a number of deaths in a short period. From January to May 1855, the King's mother (age 55), wife (33), newborn son and his only brother (33) all died.[15][16]

In 1859, Bosco selected the experienced priest Alasonatti, 15 seminarians and one high school boy and formed them into the "Society of St. Francis de Sales." This was the nucleus of the Salesians, the religious order that would carry on his work. When the group had their next meeting, they voted on the admission of Joseph Rossi as a lay member, the first Salesian brother. The Salesian Congregation was divided into priests, seminarians and "coadjutors" (the lay brothers).

Next, he worked with estarino, Mary Mazzarello and a group of girls in the hill town of Mornese. In 1871, he founded a group of religious sisters to do for girls what the Salesians were doing for boys. They were called the "Daughters of Mary Help of Christians." In 1874, he founded yet another group, the "Salesian Cooperators." These were mostly lay people who would work for young people like the Daughters and the Salesians, but would not join a religious order.[18]

The story of the departure of the first Salesians for America in 1875 is based on the missionary ideal of Bosco. After his ordination, he would have become a missionary had not his director, Joseph Cafasso, opposed the idea. He eagerly read the Italian edition of the Annals of the Propagation of the Faith and used this magazine to illustrate his Cattolico provveduto (1853) and his Month of May booklets (1858).

When Bosco founded the Salesian Society, the thought of the missions still obsessed him, though he completely lacked the financial means at that time. One night, he dreamt again. Being on a vast plain, inhabited by primitive peoples, who spent their time hunting or fighting among themselves or against soldiers in European uniforms. Along came a band of missionaries, but they were all massacred. A second group appeared, which Bosco at once recognized as Salesians. Astonished, he witnessed an unexpected change when the fierce savages laid down their arms and listened to the missionaries. The dream made a great impression on Bosco, because he tried hard to identify the men and the country of the dream.

For three years, Bosco searched among documents, trying to get information about different countries, thus identifying the country from his dream. One day, a request came from Argentina, which turned him towards the Indians of Patagonia. To his surprise, a study of the people there convinced him that the country and its inhabitants were the ones he had seen in his dream.

He regarded it as a sign of providence and started preparing a missionary there. Adopting a way of evangelization that would not expose his missionaries suddenly to wild, uncivilized tribes, he proposed to set up bases in safe locations where their missionary efforts were to be launched.

The above request from Argentina came about as follows: Towards the end of 1874, John Bosco received letters from that country requesting that he accept an Italian parish in Buenos Aires and a school for boys at San Nicolas de los Arroyos. Gazzolo, the Argentine Consul at Savona, had sent the request, for he had taken a great interest in the Salesian work in Liguria and hoped to obtain the Salesians' help for the benefit of his country. Negotiations started after Archbishop Aneiros of Buenos Aires had indicated that he would be glad to receive the Salesians. They were successful mainly because of the good offices of the priest of San Nicolas, Pedro Ceccarelli, a friend of Gazzolo, who was in touch with and had the confidence of Bosco. In a ceremony held on January 29, 1875, Bosco was able to convey the great news to the oratory in the presence of Gazzolo. On February 5, he announced the fact in a circular letter to all Salesians asking volunteers to apply in writing. He proposed that the first missionary departure start in October. Practically all the Salesians volunteered for the missions.

By this time Italy was united under Piedmontese leadership. The poorly-governed Papal States were merged into the new kingdom. It was generally thought that Bosco supported the Pope.

The Preventive System

Bosco's capability to attract numerous boys and adult helpers was connected to his "Preventive System of Education." He believed education to be a "matter of the heart" and said that the boys must not only be loved, but know that they are loved. He also pointed to three components of the Preventive System: reason, religion and kindness. Music and games also went into the mix.

Bosco gained a reputation early on of being a saint and miracle worker. For this reason, Rua, Buzzetti, Cagliero and several others began to keep chronicles of his sayings and doings. Preserved in the Salesian archives, these remain resources for studying his life. Later on, the Salesian Lemoyne collected and combined them into 77 scrapbooks with oral testimonies and Bosco’s own Memoirs of the Oratory. His aim was to write a detailed biography. This project eventually became a nineteen-volume affair, carried out by him and two other authors. These are the Biographical Memoirs. It is clearly not the work of professional historians, but a somewhat uneven compilation of those chronicles that preserve the memories of teenage boys and young men under the spell of a remarkable and beloved father figure.

Bosco's concerns over his influence

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2010) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Shortly before his death, Bosco commented "I will reveal to you now a fear... I fear that one of ours may come to misinterpret the affection that Don Bosco had for the young, and from the way that I received their confession - really, really close - and may let himself get carried away with too much sensuality towards them, and then pretend to justify himself by saying that Don Bosco did the same, be it when he spoke to them in secret, be it when he received their confession. I know that one can be conquered by way of the heart, and I fear dangers, and spiritual harm."[19][20]

Death and canonization

Bosco died on January 31, 1888. His funeral was attended by thousands and very soon after there were popular demands to have him canonized. Accordingly, the Archdiocese of Turin began to investigate and witnesses were called to determine if his holiness were worthy of a declared Saint. As expected, the Salesians, Daughters and Cooperators gave fulsome testimonies. But many remembered Bosco’s controversies in the 1870s with Archbishop Gastaldi and some others high in the Church hierarchy thought him a loose cannon and a wheeler-dealer. In the canonization process, testimony was heard about how he went around Gastaldi to get some of his men ordained and about their lack of academic preparation and ecclesiastical decorum. Political cartoons from the 1860s and later showed him shaking money from the pockets of old ladies or going off to America for the same purpose. These cartoons were not forgotten. Opponents of Bosco, including some cardinals, were in a position to block his canonization and many Salesians feared around 1925 that they would succeed.

However, Pope Pius XI had known Bosco and pushed the cause forward. Bosco was declared Blessed in 1929 and canonized on Easter Sunday of 1934, when he was given the title of "Father and Teacher of Youth."[21]

While Bosco had been popularly known as the patron saint of illusionists, on January 30, 2002, Silvio Mantelli, petitioned Pope John Paul II to formally acclaim St. John Bosco the Patron of Stage Magicians.[22] Catholic stage magicians who practice Gospel Magic venerate Bosco by offering free magic shows to underprivileged children on his feast day.

Bosco's work was carried on by his early pupil and constant companion, Michael Rua, who was appointed Rector Major of the Salesian Society by Pope Leo XIII in 1888. Salesians of Bosco have started many schools and colleges around the world.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Giovanni Battista Lemoyne (1965). The Biographical Memoirs of Saint John Bosco (1rst ed., Volume I, 1815 - 1840, p.26). New York, Salesian Publisher, Inc.

- ^ John Morrison (1999). The Educational Philosophy of Don Bosco (Indian ed., p.51). New Delhi, Don Bosco Publications, Guwahati. ISBN 81-87637-00-5

- ^ "Salesian Cooperators". Salesians of Don Bosco, Province of Mary Help of Christians, Melbourne. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ a b "The Salesian Bulletin in the World". Eircom.net, Dublin. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Ceria, Eugenio (1983). The Bibliographical Memoirs of Saint John Bosco, volume XIII (1877 - 1878). New Rochelle, New York: Salesiana Publisher. p. 191. ISBN 0-89944-013-4.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Turin's History". Italianrus.com. Anthony Parenti. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ See Timeline of Italian unification.

- ^ "The History of Turin". About Turin. Retrieved May 09, 2010.

(...) Vittorio Emanuele II (...) began the Risorgimento's season. His first minister, Camillo Benso of Cavour; thanks to a clever net of diplomatic relationships was able to incline France to the Italian cause, against the Asburgic Austria. Turin became the destination of all the Italian exiles and liberals, who settled above to the republican cause, the Italian union one, to achieve with the collaboration of the king of Sardinia.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|trans_title=,|separator=,|month=, and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Willey, David, Magician priest wants patron saint of magic BBC News 2June 2002

- ^ http://www.magnificat.ca/cal/engl/01-31.htm

- ^ a b St. Giovanni Melchior Bosco Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2., New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907, accessed June 9, 2009

- ^ a b Craughwell, Thomas J. This Saint's for You!, pp. 156-157, Quirk Books, 2007

- ^ Jestice, Phyllis G., Holy People of the World, p. 138, ABC-CLIO, 2004

- ^ Villefranche, Jacques-Melchior, The Life of Don Bosco: Founder of the Salesian Society, pp. 15-16, Burns & Oates, 18??

- ^ a b Mendl, Michael The Dreams of St. John Bosco Journal of Salesian Studies 12 (2004), no. 2, pp. 321-348.

- ^ a b Memoirs of the Oratory of Saint Francis de Sales 1815 - 1855: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SAINT JOHN BOSCO Translated by Daniel Lyons, SDB, with notes and commentary by Eugene Ceria SDB, Lawrence Castelvecchi SDB, and Michael Mendl SDB, Ch. 55, fn. 802

- ^ Petoia, Erberto (2007). "I sinistri presagi di Don Giovanni Bosco". Medioevo: p. 70.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Patron Saints Index". Retrieved 2007-10-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Paul Pennings, "Don Bosco breathes his last. The scenario of Catholic social clubs in the Fifties and Sixties". Among Men, Among Women, Amsterdam 1983, pp. 166-175 & 598-599

- ^ Stephan Sanders,A phenomenon's bankrupcy; Don Bosco and the question of coeducation. Ibidem, pp. 159-165 e 602-603

- ^ "Catholic Online". Retrieved 2007-10-18.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Magicians Want Don Bosco Declared Their Patron 2002-01-29 Zenit News Agency

Sources and Studies

- Bosco, Giovanni (1989). Memoirs of the Oratory. Don Bosco Publications. ISBN 0899441394.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Amadei, Angelo (1965–2004). Biographical Memoirs of St. John Bosco. Don Bosco Publications.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link). These volumes translate id. (1898–1939). Memorie Biografiche di San Giovanni Bosco, 19 vol. SEI.{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - Desramaut, François (1996). Don Bosco et son Temps. SEI.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Lenti, Arthur J. (2007-). Don Bosco: History and Spirit. LAS.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help); Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: year (link) A projected 7-volume series, 4 published to date. - Stella, Pietro (1996). Don Bosco: Religious Outlook and Spirituality. John Drury. Salesiana Publishers. ISBN 0899441629.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help) - Wirth, Morand (1982). Don Bosco and the Salesians. New Rochelle, New Jersey. Don Bosco Publications. Translation of id. (1969). Don Bosco e i Salesiani: Centocinquant'anni di storia. SEI.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|city=ignored (|location=suggested) (help)

Further reading

External links

- Salesians of Don Bosco Official Website (multi-lingual website)

- Salesians of Don Bosco Official Website (Philippine North)

- Salesians of the UK

- UK Salesian (alumnus) website

- Don Bosco's important writings in original language

- Founder Statue in St Peter's Basilica

- Published Writings (italian)

- SPYS - Salesian Pastoral Youth Service

- Wikipedia neutral point of view disputes from May 2010

- 1815 births

- 1888 deaths

- People from the Province of Asti

- People from Turin (city)

- Founders of Roman Catholic religious communities

- Italian saints

- Roman Catholic saints

- 19th-century Christian saints

- Anglican saints

- Salesian Order

- Saints canonized by Pope Pius XI