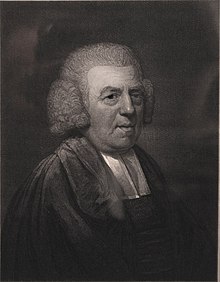

John Newton

John Henry Newton (July 24, 1725 – December 21, 1807) was an English Anglican clergyman and former slave-ship captain. He was the author of many hymns, including "Amazing Grace".

Early life

John Newton was born in Wapping, London, in 1725, the son of John Newton Sr., a shipmaster in the Mediterranean service, and Elizabeth Newton (née Seatclife), a Nonconformist Christian. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was six. [1]

Newton spent two years at boarding school. At age eleven he went to sea with his father. Newton sailed six voyages before his father retired in 1742.

Newton's father made plans for him to become a slave master at a sugar plantation in Jamaica. Instead, Newton became a captain of a slave ship.

In 1743, while on the way to visit some friends, Newton was captured and pressed into naval service by the Royal Navy. He became a midshipman aboard HMS Harwich. At one point, Newton attempted to desert and was punished in front of the crew of 350. Stripped to the waist, tied to the grating, he received a flogging of ninety-six lashes, and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman.[2][unreliable source?]

Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated suicide.[2][unreliable source?] He recovered, both physically and mentally, and, at his own request, transferred to the "Pegasus" a slave ship bound for West Africa. The ship carried goods to Africa, and traded them for slaves to be shipped to England and other countries.

Newton was a continual problem for the Pegasus crew. They left him in West Africa with a slave merchant named Amos Clowe. Clowe took Newton to the coast of Sierra Leone and gave him to his wife Princess Peye, an African duchess. Newton was abused and mistreated along with other of her slaves. It was this period that Newton later remembered as the time he was "once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa."

Early in 1748 he was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton's father to search for him.[citation needed]

Spiritual conversion

Sailing back to England in 1748 aboard the merchant ship, he experienced a spiritual conversion in the Greyhound, which was hauling a load of beeswax and dyer's wood. The ship encountered a severe storm off the coast of Donegal and almost sank. Newton awoke in the middle of the night and finally called out to God as the ship filled with water. It was this experience which he later marked as the beginnings of his conversion to evangelical Christianity. As the ship sailed home, Newton began to read the Bible and other religious literature. By the time he reached Britain, he had accepted the doctrines of Evangelical Christianity. The date was May 10, 1748, an anniversary he marked for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling, and drinking. Although he continued to work in the slave trade, he had a considerable amount of gained sympathy for the slaves.[citation needed] He later said that his true conversion did not happen until some time later: "I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards."[3]

Newton returned to Liverpool, England and, partly due to the influence of Joseph Manesty, a friend of his father's, obtained a position as first mate aboard a slave trading vessel, the Brownlow, bound for the West Indies via the coast of Guinea. During the first leg of this voyage, while in west Africa (1748–49), Newton acknowledged the inadequacy of his spiritual life. While he was sick with a fever, he professed his full belief in Christ and asked God to take control of his destiny. He later said that this experience was his true conversion and the turning point in his spiritual life. He claimed it was the first time he felt totally at peace with the Almighty God.

Still, he did not renounce the slave trade until later in his life. After his return to England in 1750, he made three further voyages as captain of the slave-trading ships Duke of Argyle (1750) and the African (1752–53 and 1753–54). He only gave up seafaring and his active slave-trading activities in 1754, after suffering a severe stroke, but continued to invest his savings in Manesty's slaving operations."[4] .

Anglican priest

In 1755 Newton became tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the port of Liverpool, again through the influence of Manesty and, in his spare time, was able to study Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac. He became well-known as an evangelical lay minister, and applied for the Anglican priesthood in 1757, although it was more than seven years before he was eventually accepted and ordained into the Church of England. Such had been his frustration during this period of rejection that he had sought also to apply to the Methodists, Independents and Presbyterians, as well as directly to the Bishops of Chester and Lincoln and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York.

Eventually, in 1764, he was introduced by Thomas Haweis to Lord Dartmouth, who was influential in recommending Newton to the Bishop of Chester, and who had suggested him for the living of Olney, Buckinghamshire. On 29 April 1764 Newton received deacon's orders, and finally became a priest on 17 June.

As curate of Olney, Newton was partly sponsored by the evangelical philanthropist John Thornton, who supplemented his stipend of £60 a year with £200 a year "for hospitality and to help the poor". He soon became well-known for his pastoral care, as much as for his beliefs, and his friendship with dissenters and evangelical clergy caused him to be respected by Anglicans and non-conformists alike. He was to spend sixteen years at Olney, during which time so popular was his preaching that the church had a gallery added to accommodate the large numbers who flocked to hear him.

Some five years later, in 1772, Thomas Scott, later to become a biblical commentator and co-founder of the Church Missionary Society, took up the curacy of the neighbouring parishes of Stoke Goldington and Weston Underwood. Newton was instrumental in converting Scott from a cynical 'career priest' to a true believer, a conversion Scott related in his spiritual autobiography The Force Of Truth (1779).

In 1779 Newton was invited by the wealthy Christian merchant John Thornton to become Rector of St Mary Woolnoth, Lombard Street, London, where he officiated until his death. The church had been built by Nicholas Hawksmoor in 1727 in the fashionable Baroque style. Newton then became one of only two evangelical preachers in the capital, and he soon found himself gaining in popularity amongst the growing evangelical party. He was a strong supporter of evangelicalism in the Church of England, and was a friend of the dissenting clergy as well as of the ministry of his own church.

Many young churchmen and others enquiring about their faith visited him and sought his advice, including such well-known social figures as the writer and philanthropist Hannah More, and the young Member of Parliament, William Wilberforce, who had recently undergone a crisis of conscience and religious conversion experience as he was contemplating leaving politics. Having sought his guidance, Newton encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament and "serve God where he was".[5][6]

In 1792, he was presented with the degree of Doctor of Divinity by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Abolitionist

John Newton has been called hypocritical by some modern writers for continuing to participate in the slave trade while holding strong Christian convictions. Newton later came to believe that during the first 5 of his 9 years as a slave trader he had not been a true Christian: "I was greatly deficient in many respects... I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time later."[7] Although this "true conversion" to Christianity also had no immediate impact on his views on slavery, he eventually came to revise them. In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet "Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade", in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave boats during the middle passage, and apologised for "a confession, which... comes too late....It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders." A copy of the pamphlet was sent to every MP, and sold so well that it swiftly required reprinting.[8]

Newton having joined English abolitionist William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the slave trade, lived to see the passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807.

Writer and hymnist

In 1767 William Cowper, the poet, moved to Olney. He worshipped in the church, and collaborated with Newton on producing a volume of hymns, which was eventually published as Olney Hymns in 1779. This work was to have a great influence on English hymnology. The volume included Newton's well-known hymns "Glorious Things of Thee are Spoken", "How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!", "Come, My Soul, Thy Suit Prepare", "Approach, My Soul, the Mercy-seat", and "Faith's Review and Expectation", came to be known by its opening phrase, "Amazing Grace".

Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the Sacred Harp.

Commemoration

- The town of Newton, Sierra Leone is named after John Newton. To this day there is a philanthropic link between John Newton's church of Olney and Newton, Sierra Leone.

- Newton was recognized for his hymns of longstanding influence by the Gospel Music Association in 1982 when he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame.

Portrayals in literature, movies and other media

- Newton is portrayed by actor John Castle in the 1975 British television miniseries "The Fight Against Slavery."

- Caryl Phillips's novel Crossing the River (1993) includes nearly verbatim excerpts from Newton's books.

- Newton is played by the actor Albert Finney in the 2006 film Amazing Grace, which highlights Newton's influence on William Wilberforce. Directed by Michael Apted, this film portrays Newton as a penitent who is haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves.

- Newton is also played by the actor Nick Moran in another 2006 film The Amazing Grace. The creation of Nigerian director/writer/producer Jeta Amata, the film provides a refreshing and creative African perspective on the familiar "Amazing Grace" theme. Nigerian actors Joke Silva, Mbong Odungide, and Fred Amata (brother of the director) portray Africans who are captured and wrested away from their homeland by slave traders.

- African Snow, a play by Murray Watts, takes place in Newton's mind. It was first produced at the York Theatre Royal as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company in April 2007 before transferring to the Trafalgar Studios in London's West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Olaudah Equiano by Israel Oyelumade.

References

- ^ The Cowper and Newton Museum

- ^ a b John Dunn, A Biography of John Newton, New Creation Teaching Ministry, 1994

- ^ John Newton. Out of the Depths. Ed. Dennis Hillman. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2003. 84.

- ^ Adam Hochschild. Bury the Chains. Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2005. 77.

- ^ Pollock 1977, p. 38

- ^ Brown 2006, p. 383

- ^ John Newton. Out of the Depths. Ed. Dennis Hillman. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2003. 84.

- ^ Adam Hochschild. Bury the Chains. Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2005. p. 130-32.

Bibliography

- Aitken, Jonathan, John Newton: From Disgrace to Amazing Grace (Crossway Books, 2007).

- Bennett, H.L. John Newton in Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 1894)

- Hindmarsh, D. Bruce. John Newton in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: University Press, 2004)

- Hochschild, Adam. Bury the Chains, The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery (Basingstoke: Pan Macmillan, 2005)

- Turner, Steve, "Amazing Grace: The Story of America's Most Beloved Song" (New York: Ecco/HarperCollins, 2002)

- Rediker, Marcus, The Slave Ship: A Human History (Viking, 2007)

- JohnNewton.org (2007)

- Bruner, Kurt & Ware, Jim, "Finding GOD in the Story of AMAZING GRACE" (Tyndale, 2007)

External links

- The John Newton Project

- Famous Quotes by John Newton

- Amazing Grace: The Song, Author and their Connection to County Donegal in Ireland

- Amazing Grace: Some Early Tunes

- The Cowper and Newton Museum, Olney

- Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade By John Newton. Published in 1788. Cornell University Library Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection. {Reprinted by}Cornell University Library Digital Collections