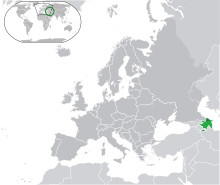

LGBT rights in Azerbaijan

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (May 2012) |

| |

| Status | Legal since 2000[1] |

| Gender identity | – |

| Military | Unknown |

| Discrimination protections | No |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition of same-sex relationships. |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned. |

| Adoption | No |

Lesbian, gay, bisexuals, and transgender (LGBT) persons in Azerbaijan may face legal challenges not experienced by non-LGBT residents. Same-sex sexual activity for both men and women is legal in Azerbaijan, but households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to heterosexual couples.

History

After declaring independence from Russia in 1918, the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic did not have laws against homosexuality. When Azerbaijan became a part of the Soviet Union in 1920, it was subject to rarely enforced Soviet laws criminalizing the practice of sex between men. Despite Vladimir Lenin having decriminalized homosexuality in Soviet Russia, sexual intercourse between men (incorrectly termed pederasty in the laws, rather than the technically accurate term sodomy) became a criminal offense in 1923 in Azerbaijan SSR,[2] punishable by up to five years in prison for consenting adults, or up to eight years if it involved force or threat.[3][4]

Azerbaijan regained its independence in 1991, and in 2000 repealed the Soviet-era anti-sodomy law.[5] A special edition of Azerbaijan, the official newspaper of the National Assembly, published on 28 May 2000, reported that the National Assembly had approved a new criminal code, and that the President had signed a decree making it law beginning in September 2000. Repeal of Article 121 was a requirement for Azerbaijan to join the Council of Europe,[6] and after sodomy was removed from the Azerbaijan criminal code in 2000, Azerbaijan became the 43rd member state of the Council on 25 January 2001.[7]

General attitude

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2012) |

Society

Like in most other Post-Soviet era countries, Azerbaijan remains a place where homosexuality is an issue surrounded by confusion. There is hardly any objective or correct information on the psychological, sociological and legal aspects of homosexuality in Azerbaijan, with the result that the majority of the society simply does not know what homosexuality is.

"Coming out" as a gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender person is therefore rare and individual LGBT people are afraid of the consequences. Thus many lead double lives, with some feeling deeply ashamed about being gay. Those who are financially independent and living in Baku, are able to lead a safe life as a LGBT person, as long as they 'practice' their homosexuality in their private sphere. There is no LGBT political movement, but there is awareness among some human rights activists and LGBT people of the need for an organisation advocating LGBT rights and protection.[8]

Although homosexual acts between consenting male adults were officially decriminalized, reports about police abuses against gays, mainly male prostitutes, have persisted. While complaining of the violence against them, the victims preferred to remain anonymous fearing retaliation on the part of police. (2001 Report of the International Helsinki Federation).

Media

There are number of LGBT figures in Azeri media but state-controlled media outlets use homosexuality as a tool to harass and discredit critics of the government[9] and opposition journalist.[10][11]

The decriminalisation of consensual same-sex male acts in 2000 was a big step forward in respect for human rights. The late President Heydar Aliyev's determination to remove any obstacles to Azerbaijan's accession to the Council of Europe was the major factor leading to the decriminalisation.

Literature

In 2009, Ali Akbar wrote a scandalous book named Artush and Zaur which was focused on homosexual love tale between an Armenian and Azerbaijani, while according to Akbar these two things - being an Armenian and being gay - are major taboos in Azeri society.

Current situation

The age of consent is equal for both heterosexual and homosexual sex, at 16 years of age. Azerbaijan is a largely secular country with one of the least practicing majority-Muslim populations.[12] The reasons behind homophobia is mostly due to the lack of knowledge about it, as well as due to the "old traditions".[13] Families of homosexuals often cannot come to terms with the latters' sexuality, especially in rural areas. Coming-out often results in violence or ostracism by the family patriarchs or forced heterosexual marriage.[14]

Until 2011, there had been no established forms of legally recognized unions for homosexuals. In 2011, the first community was formed called Gender and Development, to promote LGBT rights, and to service blogs written in the Azerbaijani language. First blog in Azerbaijani language www.freelgbt.com was founded on February 2012 by Free LGBT Azerbaijan Organization. According to the community founders, it was named so because the government would not register an openly LGBT organization.[14] There were rumors of an LGBT parade being organized in time for the Eurovision Song Contest 2012, which was hosted by Azerbaijan. This caused disagreement in the society due to homophobic views, but it did gain support from Azerbaijani human rights activists.[15] The contests presence in Azerbaijan also caused diplomatic tensions with neighbouring Iran. Iranian clerics Ayatollah Mohammad Mojtahed Shabestari and Ayatollah Ja'far Sobhani condemned Azerbaijan for "anti-Islamic behaviour", claiming that Azerbaijan was going to host a gay parade.[16] This led to protests in front of Iranian embassy in Baku, where protesters carried slogans mocking the Iranian leaders. Ali Hasanov, head of the public and political issues department in the Azeribaijani President's administration, said that gay parade claims were untrue, and warned Iran not to meddle in Azerbaijan's internal affairs.[17] In response, Iran recalled its ambassador from Baku,[18] while Azerbaijan demanded a formal apology from Iran for its statements in connection with Baku's hosting of the Eurovision Song Contest,[19] and later also recalled its ambassador from Tehran.[20]

LGBT Organizations

As of 2013, there are 4 LGBT organizations in Azerbaijan. 'Gender and Development' - created in 2007 and carries out local projects in collaboration with the Ministry of Health. Nefes LGBT Azerbaijan - established in 2012. It has implemented several projects, including part of an international survey and regularly holds talks with the EU Delegation to Azerbaijan and other European embassies regarding to the difficulties of LGBT people and their situation in Azerbaijan.

Living conditions

See also

Notes

- ^ State-sponsored Homophobia A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults

- ^ Healey, Dan. "Masculine purity and 'Gentlemen's Mischief': Sexual Exchange and Prostitution between Russian Men, 1861–1941". Slavic Review. Vol. 60, No. 2 (Summer, 2001), p. 258.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Azerbaijan: Information On The Treatment Of Homosexuals". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ Russian S.F.S.R. (1966). Harold Joseph Berman (ed.). Soviet criminal law and procedure: the RSFSR codes (University of California original). Harvard University Press. p. 196.

{{cite book}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help) - ^ Spartacus International Gay Guide, page 1216. Bruno Gmunder Verlag, 2007.

- ^ "Council of Europe". Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ^ Dennis van der Veur, Forced Out;LGBT people in Azerbaijan, report for ILGA, 2007

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (6 May 2008). "Azerbaijan: State media embroiled in gay bashing controversy". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (10 April 2008). "Azerbaijan: Opposition journalist says he is victim of vicious smear campaign". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Amnesty International Report 2009 – Azerbaijan". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ GALLUP WorldView - data accessed on 17 january 2009

- ^ Gays and Lesbians of Azerbaijan

- ^ a b Western Media on Eurovision. Radio Liberty. 25 May 2012.

- ^ Gay parade in Baku: to be or not to be?

- ^ Antidze, Margarita (22 May 2012). "Iran's "gay" Eurovision jibes strain Azerbaijan ties". Reuters. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ Lomsadze, Girgoi (21 May 2012). "Azerbaijan: Pop Music vs. Islam". EurasiaNet.org. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Iran recalls envoy to Azerbaijan ahead of Eurovision". AFP. 22 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Demands Apology From Iran Over Eurovision". Voice of America. 24 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.

- ^ "Azerbaijan Recalls Ambassador To Iran". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 30 May 2012. Retrieved 15 July 2012.