Leopold and Loeb

Nathan Leopold | |

|---|---|

Nathan Leopold in Stateville Penitentiary, 1931 | |

| Born | Nathan Freudenthal Leopold, Jr. November 19, 1904 Chicago, United States |

| Died | August 29, 1971 (aged 66) Puerto Rico |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Criminal charge | Murder, kidnapping |

| Penalty | Life + 99 years imprisonment |

Richard Loeb | |

|---|---|

Richard Loeb (left) and Nathan Leopold (right) | |

| Born | Richard Albert Loeb June 11, 1905 Chicago, United States |

| Died | January 28, 1936 (aged 30) Joliet, Illinois, United States |

| Cause of death | Knife attack |

| Criminal status | Deceased |

| Criminal charge | Murder, Kidnapping |

| Penalty | Life +99 years imprisonment |

Nathan Freudenthal Leopold, Jr. (November 19, 1904 – August 29, 1971)[1] and Richard Albert Loeb (June 11, 1905 – January 28, 1936), more commonly known as "Leopold and Loeb", were two wealthy University of Chicago law students who kidnapped and murdered 14-year-old Robert "Bobby" Franks in 1924 in Chicago.[2]

The duo was motivated to murder Franks by their desire to commit a perfect crime.

Once apprehended, Leopold and Loeb retained Clarence Darrow as counsel for the defense. Darrow’s summation in their trial is noted for its influential criticism of capital punishment as retributive, rather than a rehabilitative penal system. Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life imprisonment. Loeb was killed by a fellow prisoner in 1936; Leopold was released on parole in 1958.

The Leopold and Loeb crime has been the inspiration for several works in film, theatre, and fiction, such as the 1929 play Rope by Patrick Hamilton, and Alfred Hitchcock's take on the play in the 1948 film of the same name. Later movies such as Compulsion and Swoon were more accurate portrayals of the Leopold and Loeb case.

Early lives

Nathan Leopold

Nathan Leopold was born on November 19, 1904 in Chicago, Illinois, to a wealthy immigrant Jewish family from Germany.[3] Nathan Leopold was a child prodigy who spoke his first words at the age of four months;[3] shocking and amazing nannies and caretakers. He reportedly had an intelligence quotient of 210,[4] although this is not directly comparable to scores on modern IQ tests.[5] At the time of the murder, Leopold had already completed an undergraduate degree at the University of Chicago, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, and was attending law school at the University of Chicago.[6] He claimed to have been able to speak 27 languages fluently,[7] and was a skilled ornithologist.[8] Leopold and several other ornithologists were the first to discover the Kirtland's Warbler in their area in over half a century. Film from the early 1920s shows Leopold participating in the discovery. Leopold planned to transfer to Harvard Law School in September 1924 after taking a trip to Europe. He was thought of as having a brilliant mind.

Richard Loeb

Richard Loeb was born on June 11, 1905, in Chicago to the family of Anna Henrietta (née Bohnen) and Albert Henry Loeb, a wealthy lawyer and vice president of Sears.[9] His father was Jewish and his mother was Catholic.[10] Like Leopold, Loeb was exceptionally intelligent, and skipped several grades in school. However, Loeb was more focused on non-academic activities. Loeb remains the youngest graduate in the history of the University of Michigan. Loeb planned to enter the University of Chicago Law School after taking some postgraduate courses.[6]

Lead up

Both Leopold and Loeb lived in the affluent Kenwood neighborhood on Chicago's Southside, some six miles south of downtown. Loeb's father, Albert, began his career as a lawyer and became the vice president of Sears and Roebuck. Besides owning an impressive mansion in Kenwood, two blocks from the Leopold home, the Loeb family had a summer estate, Castle Farms, in Charlevoix, Michigan.

Although Leopold and Loeb knew each other casually while growing up, their relationship flourished when they met at the University of Chicago. They quickly formed a strong friendship. Leopold and Loeb found that they had a mutual interest in crime, Leopold being particularly interested in Friedrich Nietzsche's theory of the superman. Leopold and Loeb began to commit crimes. Leopold agreed to act as Loeb's accomplice.[11] They began with petty theft and vandalism. They broke into a fraternity house at the university and stole penknives, a camera and a typewriter (later used to type the ransom letter). They soon committed a series of more serious crimes such as arson.

The pair was disappointed with the lack of media coverage of their crimes. Leopold and Loeb then decided to commit a "perfect crime" that would garner public attention.

The Superman

Because of Leopold's strong interest in Nietzsche, Leopold and Loeb believed themselves to be Nietzschean supermen (Übermenschen) who could commit a "perfect crime" (in this case, a kidnapping and murder).[6] Nietzsche suggested that superior minds could rise above the laws and rules that bound the average man. The average man was inferior and unimportant to those of superior qualities. This theory fed Leopold with the will to prove himself to be a truly brilliant mind. Before the murder, Leopold had written to Loeb: "A superman ... is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern men. He is not liable for anything he may do."[12]

Murder of Robert Franks

The pair planned to kidnap and murder a young boy at random as their perfect crime. They would send the boy's family a ransom letter, although the crime was not for money, as the two men's families supplied them with money. Instead, the ransom note was a mere prop for their crime. Leopold and Loeb spent seven months planning the murder. They covered everything from the disposal of the body to the murder weapon and how the ransom note was to be written. They also discussed the method of receiving ransom money with little or no risk of being caught.[13] They made sure that their plan would leave as little evidence as possible. Leopold was to hire a rental car for the murder. This was the vehicle into which the young boy would be lured and then killed. He used the fake name "Morten D. Ballad" to hire the car. A chisel was purchased—this would be the murder weapon. When Leopold and Loeb were certain that they had perfected their plans, they put their plot into motion on Wednesday, May 21, 1924. At this time, Leopold was 19 and Loeb was 18.

The pair drove around the Harvard School For Boys (closed 1962) in the Kenwood area,[14] where Loeb himself had been educated, looking for a young boy that they would be able to kill. They spent much time both driving around and walking the grounds. They kept themselves hidden in fear of being seen. Leopold even admitted to having watched the boys from a distance using his bird viewing binoculars. The pair finally decided upon Robert "Bobby" Franks, the 14-year-old son of Chicago millionaire Jacob Franks. Loeb knew Bobby Franks well, for he was his second cousin and neighbor and had played tennis at the Loeb residence several times. Their choice of victim was at random. Future Hollywood producer Armand Deutsch, the then 11-year-old grandson of Julius Rosenwald, later claimed that he might have been the intended victim of Loeb or Leopold. However, on the day of the murder, he was picked up by his family's chauffeur after school because he had a dental appointment.[15][16]

The car pulled up alongside Franks, and he was offered a ride. At first he refused. However, Loeb pressed on and eventually convinced the boy to ride with them because he wanted to discuss a tennis racket Bobby Franks had been using. Franks was lured into the passenger seat of their rented car. Either Loeb or Leopold (it is uncertain which) then drove while the other sat in the back armed with the taped chisel, a weapon commonly chosen by Loeb.

It is still unknown exactly who struck Franks, but it is commonly believed that it was Loeb who struck Franks several times in the head with the chisel before dragging him into the back seat of the car, while Leopold drove. At this point, Franks was gagged with a rag and soon thereafter lost consciousness. After driving into the country near the Indiana line, they pulled the car over and Loeb moved from the back to the passenger seat as the body of the boy lay covered in the back of the car.[17]

Leopold and Loeb had decided that they would hide the body near Wolf Lake in Hammond, Indiana. With the body on the floor of the car and covered out of view, the killers drove to their dumping spot. This was an area Leopold was very familiar with, for he had gone bird-watching there many times. The killers thought it was wise to choose a familiar area. Leopold and Loeb had their dinner at a small sandwich place. After finishing their meal, the two waited until nightfall. When it was dark enough for them to proceed with the dumping of the body, they removed Franks's clothes and left them at the side of the road. They poured hydrochloric acid[18] on the face, genitals and a distinctive abdomen scar to make identification more difficult; the boy's circumcision would reveal him as Jewish. They concealed the body in a culvert at the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks near 118th Street, north of Wolf Lake. They then left the scene and began to travel home.

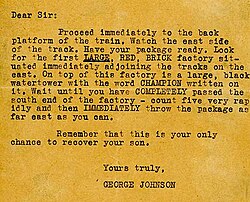

By the time Leopold and Loeb returned to Chicago, word had already spread about Franks's disappearance. Leopold called Franks's mother and informed her that her son had been kidnapped. He used the name "George Johnson" when he called, which was the same name used in the ransom note. They later mailed this ransom letter to the Franks family, typed on a stolen typewriter. They burned their blood-spotted clothing. They also attempted to clean bloodstains from the upholstery of the rented automobile. The two then spent the rest of the evening playing cards.

The Franks family received the ransom note the following morning. The same day, Leopold and Loeb called the Frankses a second time, instructing them to travel to a local drugstore where further instructions would be given to them. In the stress of the situation, the address of the store was forgotten by the receiver of the call. Before the Franks family could pay the ransom, Tony Minke, a Polish immigrant, came across the body that was later confirmed to be Bobby Franks.[13][17] When Leopold and Loeb learned that the body had been found, they destroyed the typewriter used to write the ransom note and burned the robe used to move the body.[13][17] Convinced that they had done everything they could to hide their tracks, Leopold and Loeb went about their lives as usual.

Police investigations were now widely spread around Chicago. Rewards were guaranteed to any members of the public who were able to provide the police with clues. Though Loeb went about his day-to-day routine quietly, Leopold involved himself in the police investigations as much as possible. He offered theories to reporters and whoever else would listen. When speaking with a detective, Leopold went so far as to say, "If I were to murder anybody, it would be such a cocky little son of a bitch as Bobby Franks".[19]

For a while, the hunt for clues seemed hopeless. However, Detective Hugh Patrick Byrne, while searching for evidence, discovered a pair of eyeglasses near the body. Though common in prescription and frame, these glasses were equipped with an unusual hinge mechanism (patent 1,342,973[20]). In Chicago, only three people had purchased glasses with such a mechanism, one of whom was Nathan Leopold.[21] (Leopold's glasses are now in the Chicago History Museum.[22]) The destroyed typewriter used for the ransom note was also found soon after. Upon being questioned, Leopold told police he had possibly lost the glasses while bird-watching the previous week.[23] When asked by the detective to demonstrate how the glasses would have fallen from his pocket, Leopold suggested that he might have tripped on a tree root. He placed the glasses in his jacket pocket and threw himself onto the ground. However, despite multiple tries, Leopold's glasses remained in place.[citation needed] Suspicions about the two boys began to circulate among the public.

Loeb was also taken in for questioning on May 29, 1924.[24] Loeb told the police that Leopold was with him the night of the murder. Leopold and Loeb claimed they had picked up two women (Edna and May) in Leopold's car and had dropped them off near a golf course, never learning their last names. They both insisted that they drove in Leopold's car. However, while the boys were being questioned, Leopold's chauffeur came by the police station to drop off pajamas and toiletry supplies in case the police were to keep him at the station overnight. As he was leaving, the chauffeur insisted that the boys could not have possibly been involved with the murder. He claimed that he was repairing Leopold's car at the time of the murder. By the chauffeur's logic, the boys could not have possibly driven anywhere, let alone as far as Wolf Lake. The chauffeur's wife later confirmed that the car had been in the Leopold garage that night.

Confession

Loeb confessed first. He insisted that Leopold had planned everything. He claimed that Leopold was the one who sat in the back of the car and killed Bobby Franks. Loeb said that he drove the car. Leopold was in another room at the time of the confession. He initially stuck by what he had told the police earlier. However, when Leopold was informed that his partner had confessed, his confession swiftly followed.[25] Leopold insisted that he was driving the car while Loeb sat in the back. He said that it was Loeb who killed Bobby. Although their confessions corroborated most of the facts in the case, each blamed the other for the actual killing.[13][17] Most commentators believe that Loeb struck the blow that killed Franks.[11] However, which of the two actually wielded the weapon that killed Franks is not known. Psychiatrists at the trial, impressed by Leopold's intelligence, agreed that Loeb had struck the fatal blow. Nevertheless, the circumstantial evidence in the case, including eyewitness testimony by Carl Ulvigh (who saw Loeb driving with Leopold in the back seat minutes before the kidnapping), suggests that Leopold may have been the killer.[26]

Motive

The ransom was not their primary motive; the young men's families provided them all the money that they needed. Both had admitted that they were driven by the thrill of the kill and the desire to commit the "perfect crime".[6] The Superman theory may have only deepened the boys' obsession with crime and caused them to think that they were above the law, and therefore could not be caught. The fact that two wealthy teenagers kidnapped and murdered a young boy at random confused, baffled, and angered the public.[citation needed]

Trial

The trial of Leopold and Loeb became a media spectacle. Held at Courthouse Place, it was one of the first cases in the U.S. to be dubbed the "Trial of the Century".[27] Fearing that their child would receive a death sentence, Loeb's family hired 67-year-old Clarence Darrow — a well-known opponent of capital punishment — to defend the young men against the capital charges of murder and kidnapping.[28] Darrow was one of the best criminal lawyers in the country and rumors circulated that his fee was a million dollars. Some were surprised that he had accepted the case considering the physical evidence, confessions, and the nature of the crime that had been committed.

While the media expected Leopold and Loeb to plead not guilty by reason of insanity, Darrow changed the plea of his clients to plead guilty, in order to avoid a jury trial, which he believed would likely have resulted in the death penalty.[28] The case was heard by Cook County Circuit Court Judge John R. Caverly. Darrow believed Caverly to be a soft-hearted and concerned judge and he hoped that he would be able to convince him to let the men off with a life sentence rather than death.

Darrow's speech

During the 12-hour hearing on the final day, Darrow gave a speech that has been called the finest of his career[29] and a "masterful plea."[30] It was aimed at the inhuman punishments and ways of the American justice system. The speech included the following:

This terrible crime was inherent in his organism, and it came from some ancestor... Is any blame attached because somebody took Nietzsche's philosophy seriously and fashioned his life upon it?... It is hardly fair to hang a 19-year-old boy for the philosophy that was taught him at the university.[31]

Darrow's argument lasted for almost twelve hours. He touched on everything from the young age of his clients to the plea for mercy.

This was part of Darrow's court argument:

Now, your Honor, I have spoken about the war. I believed in it. I don’t know whether I was crazy or not. Sometimes I think perhaps I was. I approved of it; I joined in the general cry of madness and despair. I urged men to fight. I was safe because I was too old to go. I was like the rest. What did they do? Right or wrong, justifiable or unjustifiable—which I need not discuss today—it changed the world. For four long years the civilized world was engaged in killing men. Christian against Christian, barbarian uniting with Christians to kill Christians; anything to kill. It was taught in every school, aye in the Sunday schools. The little children played at war. The toddling children on the street. Do you suppose this world has ever been the same since? How long, your Honor, will it take for the world to get back the humane emotions that were slowly growing before the war? How long will it take the calloused hearts of men before the scars of hatred and cruelty shall be removed?

We read of killing one hundred thousand men in a day. We read about it and we rejoiced in it—if it was the other fellows who were killed. We were fed on flesh and drank blood. Even down to the prattling babe. I need not tell you how many upright, honorable young boys have come into this court charged with murder, some saved and some sent to their death, boys who fought in this war and learned to place a cheap value on human life. You know it and I know it. These boys were brought up in it. The tales of death were in their homes, their playgrounds, their schools; they were in the newspapers that they read; it was a part of the common frenzy—what was a life? It was nothing. It was the least sacred thing in existence and these boys were trained to this cruelty.

It will take fifty years to wipe it out of the human heart, if ever. I know this, that after the Civil War in 1865, crimes of this sort increased, marvelously. No one needs to tell me that crime has no cause. It has as definite a cause as any other disease, and I know that out of the hatred and bitterness of the Civil War crime increased as America had never seen before. I know that Europe is going through the same experience today; I know it has followed every war; and I know it has influenced these boys so that life was not the same to them as it would have been if the world had not made red with blood. I protest against the crimes and mistakes of society being visited upon them. All of us have a share in it. I have mine. I cannot tell and I shall never know how many words of mine might have given birth to cruelty in place of love and kindness and charity.

Your Honor knows that in this very court crimes of violence have increased growing out of the war. Not necessarily by those who fought but by those that learned that blood was cheap, and human life was cheap, and if the State could take it lightly why not the boy? There are causes for this terrible crime. There are causes as I have said for everything that happens in the world. War is a part of it; education is a part of it; birth is a part of it; money is a part of it—all these conspired to compass the destruction of these two poor boys.

Has the court any right to consider anything but these two boys? The State says that your Honor has a right to consider the welfare of the community, as you have. If the welfare of the community would be benefited by taking these lives, well and good. I think it would work evil that no one could measure. Has your Honor a right to consider the families of these defendants? I have been sorry, and I am sorry for the bereavement of Mr. and Mrs. Franks, for those broken ties that cannot be healed. All I can hope and wish is that some good may come from it all. But as compared with the families of Leopold and Loeb, the Franks are to be envied—and everyone knows it.

I do not know how much salvage there is in these two boys. I hate to say it in their presence, but what is there to look forward to? I do not know but what your Honor would be merciful to them, but not merciful to civilization, and not merciful if you tied a rope around their necks and let them die; merciful to them, but not merciful to civilization, and not merciful to those who would be left behind. To spend the balance of their days in prison is mighty little to look forward to, if anything. Is it anything? They may have the hope that as the years roll around they might be released. I do not know. I do not know. I will be honest with this court as I have tried to be from the beginning. I know that these boys are not fit to be at large. I believe they will not be until they pass through the next stage of life, at forty-five or fifty. Whether they will then, I cannot tell. I am sure of this; that I will not be here to help them. So far as I am concerned, it is over.

I would not tell this court that I do not hope that some time, when life and age have changed their bodies, as they do, and have changed their emotions, as they do—that they may once more return to life. I would be the last person on earth to close the door of hope to any human being that lives, and least of all to my clients. But what have they to look forward to? Nothing. And I think here of the stanza of Housman:

Now hollow fires burn out to black,

And lights are fluttering low:

Square your shoulders, lift your pack

And leave your friends and go.

O never fear, lads, naught’s to dread,

Look not left nor right:

In all the endless road you tread

There’s nothing but the night.I care not, your Honor, whether the march begins at the gallows or when the gates of Joliet close upon them, there is nothing but the night, and that is little for any human being to expect.

But there are others to consider. Here are these two families, who have led honest lives, who will bear the name that they bear, and future generations must carry it on.

Here is Leopold’s father—and this boy was the pride of his life. He watched him, he cared for him, he worked for him; the boy was brilliant and accomplished, he educated him, and he thought that fame and position awaited him, as it should have awaited. It is a hard thing for a father to see his life's hopes crumble into dust.

Should he be considered? Should his brothers be considered? Will it do society any good or make your life safer, or any human being’s life safer, if it should be handled down from generation to generation, that this boy, their kin, died upon the scaffold?

And Loeb’s the same. Here are the faithful uncle and brother, who have watched here day by day, while Dickie’s father and his mother are too ill to stand this terrific strain, and shall be waiting for a message which means more to them than it can mean to you or me. Shall these be taken into account in this general bereavement?

Have they any rights? Is there any reason, your Honor, why their proud names and all the future generations that bear them shall have this bar sinister written across them? How many boys and girls, how many unborn children will feel it? It is bad enough as it is, God knows. It is bad enough, however it is. But it’s not yet death on the scaffold. It’s not that. And I ask your Honor, in addition to all that I have said to save two honorable families from a disgrace that never ends, and which could be of no avail to help any human being that lives.

Now, I must say a word more and then I will leave this with you where I should have left it long ago. None of us are unmindful of the public; courts are not, and juries are not. We placed our fate in the hands of a trained court, thinking that he would be more mindful and considerate than a jury. I cannot say how people feel. I have stood here for three months as one might stand at the ocean trying to sweep back the tide. I hope the seas are subsiding and the wind is falling, and I believe they are, but I wish to make no false pretense to this court. The easy thing and the popular thing to do is to hang my clients. I know it. Men and women who do not think will applaud. The cruel and thoughtless will approve. It will be easy today; but in Chicago, and reaching out over the length and breadth of the land, more and more fathers and mothers, the humane, the kind and the hopeful, who are gaining an understanding and asking questions not only about these poor boys, but about their own—these will join in no acclaim at the death of my clients.

These would ask that the shedding of blood be stopped, and that the normal feelings of man resume their sway. And as the days and the months and the years go on, they will ask it more and more. But, your Honor, what they shall ask may not count. I know the easy way. I know the future is with me, and what I stand for here; not merely for the lives of these two unfortunate lads, but for all boys and all girls; for all of the young, and as far as possible, for all of the old. I am pleading for life, understanding, charity, kindness, and the infinite mercy that considers all. I am pleading that we overcome cruelty with kindness and hatred with love. I know the future is on my side. Your Honor stands between the past and the future. You may hang these boys; you may hang them by the neck until they are dead. But in doing it you will turn your face toward the past. In doing it you are making it harder for every other boy who in ignorance and darkness must grope his way through the mazes which only childhood knows. In doing it you will make it harder for unborn children. You may save them and make it easier for every child that sometime may stand where these boys stand. You will make it easier for every human being with an aspiration and a vision and a hope and a fate. I am pleading for the future; I am pleading for a time when hatred and cruelty will not control the hearts of men. When we can learn by reason and judgment and understanding and faith that all life is worth saving, and that mercy is the highest attribute of man.

I feel that I should apologize for the length of time I have taken. This case may not be as important as I think it is, and I am sure I do not need to tell this court, or to tell my friends that I would fight just as hard for the poor as for the rich. If I should succeed, my greatest reward and my greatest hope will be that for the countless unfortunates who must tread the same road in blind childhood that these poor boys have trod—that I have done something to help human understanding, to temper justice with mercy, to overcome hate with love.

I was reading last night of the aspiration of the old Persian poet, Omar Khayyam. It appealed to me as the highest that I can vision. I wish it was in my heart, and I wish it was in the hearts of all:

So I be written in the Book of Love,

I do not care about that Book above.

Erase my name or write it as you will,

So I be written in the Book of Love.

Darrow succeeded in persuading the judge to waive the death penalty. The judge sentenced Leopold and Loeb each to life imprisonment for the murder and 99 years each for the kidnapping.[28] This was mainly on the grounds that, being under 21, Leopold and Loeb were legal minors. Shortly thereafter, on October 27, 1924, Loeb's father, Albert Henry Loeb, died of heart failure.[32]

Prison

Leopold and Loeb were initially held at Joliet Prison. Although they were kept apart as much as possible, the two managed to retain their relationship. Leopold was later transferred to Stateville Penitentiary. Loeb was soon transferred there as well. Once reunited, the two taught classes in the prison school.[33]

Loeb's death

Initially, both Leopold and Loeb were receiving money from their families, but this was later cut to five dollars per week. The money was used to purchase goods such as cigarettes from the prison store. Other prisoners were not aware that Leopold and Loeb were no longer receiving larger amounts of money. They were both seen as rich snobs. This made them targets for other prisoners. One day in the prison yard, Leopold was threatened at knife point for money. After trying to explain that he didn't have any, he was saved when Loeb and some of his other friends intervened.

The allowance cut had also caused problems for Loeb. Some of Loeb's money went to former cell-mate of his, James E. Day, as a bribe not to hurt him. After several accounts of abuse and threatening, Day was moved away from Loeb.

On January 28, 1936, Leopold and Loeb were working on assignment at the prison school. While they were working, Day passed them and reportedly said "I'll see you later" (referring to Loeb). Loeb was later attacked by Day with a straight razor (shaving blade) in a shower room. He was taken directly to the prison hospital where doctors tried to save his life. Leopold went to the hospital to find his friend barely conscious and slashed all over. Leopold offered to have his blood tested for a transfusion but was denied by the doctors, who knew there was no hope. Loeb's last words to Leopold were "I think I'm going to make it." Leopold then washed his friend's body as an act of affection.

Day claimed afterward that Loeb had attempted to sexually assault him. However, it may have been the other way around. Rumors suggested that Day had desired sexual favors from Loeb, who refused him. Many doubted that Day's story was true. It wasn't likely that he acted in self-defense. Day emerged unharmed from the attack, while Loeb sustained more than 50 wounds from the attack, including numerous self-defense wounds on his arms and hands. Loeb's throat had also been slashed from behind suggesting that he was attacked by surprise. Nevertheless, an inquiry accepted Day's testimony. The prison authorities, perhaps embarrassed by publicity sensationalizing alleged decadent behavior in the prison, ruled that Day's attack on Loeb was indeed in self-defense.[6][33] According to one widely reported account, newsman Ed Lahey wrote this lead for the Chicago Daily News: "Richard Loeb, despite his erudition, today ended his sentence with a proposition."[34][35] Some papers went as far as to say that Loeb deserved what he got, and appeared to praise James Day for his murder.

Another possible motive for Loeb's murder was money. Because his money had been cut Loeb could no longer afford to bribe Day with gifts in return for safety.[36]

There is no evidence that Loeb was a sexual predator while in prison; however, Loeb's murderer was later caught on at least one occasion engaging a fellow inmate sexually[37] as well as committing numerous other infractions. In an autobiography entitled Life Plus 99 Years, Leopold referred to Day's claims that Loeb had attempted to sexually assault him as ridiculous and laughable. This is echoed in an interview with the Catholic chaplain at the prison, Father Eligius Weir, who had been a personal confidant of Richard Loeb. Weir stated that James Day had been the sexual predator and had gone after Loeb because Loeb refused to have sexual relations with him.[38]

Leopold dedicated much time to reclaim Loeb's name, who had died a famous child killer and a named sexual predator. Leopold composed books for the prison school. On the cover of these books he wrote in Latin "Ratione autem liberamur" which translates to "by reason, however, we are set free."

Although Leopold continued with his work in prison after Loeb's death, he suffered from depression. Leopold reportedly screamed for hours in his cell before being moved to the prison psychologists. This was meant to help him, but according to Leopold it was a punishment because Loeb's killer, James Day was also among the patients.

Leopold's later life

After organizing the prison library, setting up a better schooling system, teaching students, writing an autobiography, and working in the prison hospital, Leopold volunteered for the Stateville Penitentiary Malaria Study in 1944, in which he was deliberately infected with malaria and subjected to multiple experimental treatments.[39]

After rejections from many publishers, Leopold's autobiography, Life Plus 99 Years, was published in 1954. Numerous parole petitions were unsuccessful. One day a man named Meyer Levins visited Leopold. Levins had attended school with Leopold and Loeb at the University of Chicago and believed that the true story had been misunderstood. He wanted to write a book to explain to the public what really happened. Leopold responded that he did not wish his story to be told in third person form, but offered Levins a chance to contribute to his autobiography. Levins, unhappy with that suggestion, went ahead with his book alone. Leopold later said that reading the book, entitled Compulsion, made him sick. Although the court scenes were accurate, Leopold said that the characters could not be further off. Levins' attempt at straightening the story, in Leopold's opinion, did nothing but obscure it further.[citation needed]

Early in 1958 Leopold was released on parole after 33 years in prison.[6][7] In April of that year he attempted to set up the Leopold Foundation, to be funded by royalties from Life Plus 99 Years, "to aid emotionally disturbed, retarded, or delinquent youths".[40][6][7][41] The State of Illinois voided his charter, however, on grounds that it violated the terms of his parole.[42]

Leopold moved to Puerto Rico to avoid media attention and married a widowed florist.[6][7] The Brethren Service Commission, a Church of the Brethren affiliated program, accepted him as a medical technician at its hospital in Puerto Rico. He expressed his appreciation in an article: "To me the Brethren Service Commission offered the job, the home, and the sponsorship without which a man cannot be paroled. But it gave me so much more than that, the companionship, the acceptance, the love which would have rendered a violation of parole almost impossible."[43] He was known as "Nate" to neighbors and co-workers at Castañer General Hospital in Adjuntas, Puerto Rico, where he worked as a laboratory and x-ray assistant.[44] During this period he was active in the Natural History Society of Puerto Rico, traveling throughout the island to observe its birdlife. In 1963 he published Checklist of Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Leopold spoke of his intention to write a book entitled Snatch for a Halo, about his life following prison, but never did so. Later, he tried to block production of the movie Compulsion on the grounds of invasion of privacy, defamation, and profiting from his life story.[44]

He died of a diabetes-related heart attack on August 29, 1971, at the age of 66.[6][7] His corneas were donated.[6]

In popular culture

Leopold and Loeb have been the inspiration for several works in film, theatre, and fiction, such as the 1929 play Rope by Patrick Hamilton, which was performed on BBC television in 1939[45] and served as the basis for Alfred Hitchcock's film of the same name in 1948.[46] Fictionalized versions of the events were also included in Meyer Levin's 1956 novel Compulsion and its 1959 film adaptation.[46] Never the Sinner, John Logan's 1988 play [47] (subsequently revised for its 1995 Chicago production) was based on contemporary newspaper accounts and made explicit a homosexual relationship between the two killers.[48]

The case served as inspiration for numerous works, including Richard Wright's 1940 novel Native Son, Tom Kalin's 1992 film Swoon, Michael Haneke's 1997 film Funny Games (and an American shot-for-shot remake in 2008); Barbet Schroeder's Murder by Numbers (2002); Stephen Dolginoff's 2005 Off-Broadway musical Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story; and various TV episodes (including on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit).

See also

References

- ^ NATHAN LEOPOLD (1904-1971), Social Security Death Index

- ^ Homicide in Chicago 1924 Leopold & Loeb Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ a b "Nathan Leopold biography". The Biography Channel. 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ The Biography Channel "Notorious Crime Profiles: Leopold and Loeb, Partners in Crime", Retrieved January 5, 2009.

- ^ Perleth, Christoph; Schatz, Tanja; Mönks, Franz J. (2000). "Early Identification of High Ability". In Heller, Kurt A.; Mönks, Franz J.; Sternberg, Robert J.; Subotnik, Rena F. (eds.). International Handbook of Giftedness and Talent (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Pergamon. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-08-043796-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Leopold and Loeb Trial:A Brief Account by Douglas O. Linder. 1997. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Crime Library - "Freedom" by Marilyn Bardsley. Crime Library — Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Rapai, William. (2012). The Kirtland's warbler : the story of a bird's fight against extinction and the people who saved it. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-472-11803-8.

- ^ "Richard Loeb biography". The Biography Channel. 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2012.

- ^ http://www.crimelibrary.com/notorious_murders/famous/loeb/5d.html

- ^ a b Denise Noe (February 29, 2004). "Leopold and Loeb's Perfect Crime". Crime Magazine.

- ^ Simon Baatz, For the Thrill of It. New York: Harper, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Statement of Nathan F. Leopold Northwestern University Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ "Leopold & Loeb kill Bobby Franks - Chicago, IL". Waymarking.com.

- ^ "New York Social Diary". Retrieved July 8, 2008.

- ^ Purdum, Todd S. (August 18, 2005). "Armand S. Deutsch, Hollywood fixture, dies at 92". The New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Statement of Richard Loeb Northwestern University Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ Crime Library – Enter Clarence Darrow. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

- ^ "Darrow Will Drop Carefully Reared Insanity Defense". The Sunday Morning Star. July 27, 1924. p. 1.

- ^ Shreiner, E.E.; Hinge for eyeglass or spectacle frames; June 8, 1920; retrieved February 17, 2013;

- ^ The Glasses: The Key Link to Leopold and Loeb UMKC Law. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Yen, Johnny; "The Greatest Sin"; October 30, 2007; retrieved February 17, 2013;

- ^ Chicago Daily News, June 2, 1924

- ^ Urbana Daily Courier, October 28, 1924

- ^ Chicago Daily News, September 10, 1924, pg.3

- ^ Leopold, Loeb & The Crime of the Century, by Hal Higdon, pg 319

- ^ JURIST - The Trial of Leopold and Loeb, Prof. Douglas Linder. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c Gilbert Geis and Leigh B. Bienen, Crimes of the Century (Boston, 1998).

- ^ -The Clarence Darrow Home Page, The Leopold and Loeb Trial Home Page, Prof. Douglas Linder. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Urbana Daily Courier, September 10, 1924

- ^ John Thomas Scopes, World's greatest court trial. Cincinnati : National Book Co., 1925, pp. 178-179, 182.

- ^ Daily Illini, University of Illinois, October 28, 1924

- ^ a b Leopold worked in the prison hospital and showed that he was the perfect model prisoner. He has also organised the prison library. Leopold later said that all his good work later in life was a way of making up for his earlier crime. Life & Death In Prison by Marilyn Bardsley. Crime Library — Courtroom Television Network, LLC. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- ^ Dr. Ink (August 23, 2002). "Ask Dr. Ink". Poynter Online.

- ^ Murray, Jesse George (1965). The madhouse on Madison Street,. Follett Pub. Co. p. 344.

- ^ Leopold, Loeb & The Crime of the Century by Hal Higdon, pg 292

- ^ Leopold, Loeb & The Crime of the Century, pg 302

- ^ Leopold, Loeb & The Crime of the Century, pg 293

- ^ Leopold, Nathan F., Jr. Life Plus 99 Years. Lowe and Brydone (Printers) Limited, 1958.

- ^ Daily Defender; May 29, 1958; p9

- ^ Life Plus 99 Years. Intro. By Erle Stanley Gardner, by Leopold, Nathan Freudenthal. Publisher: Garden City, NY, Doubleday, 1958.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune, July 16, 1958 p.23

- ^ "The Companionship, the Acceptance." The Brethren Encyclopedia. Vol. 2 1983. Print.

- ^ a b "E-mailed comment". Law.umkc.edu. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ "Rope (1939)". IMDb.com. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Jake Hinkson (October 19, 2012). "Leopold and Loeb Still Fascinate 90 Years Later". criminalelement.com. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ^ Logan, Josh. "Never the Sinner". Samuel French. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Christiansen, Richard. "Revised `Never The Sinner' An Even More Riveting Work". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

Bibliography

- Leopold, Nathan F. Life plus 99 Years, 1958 (Introduction by Erle Stanley Gardner)

- Baatz, Simon. For the Thrill of It: Leopold, Loeb and the Murder that Shocked Chicago (HarperCollins, 2008).

- Baatz, Simon. "Criminal Minds", Smithsonian Magazine 39 (August 2008): 70-79.

- Higdon, Hal. Leopold and Loeb: The Crime of the Century, University of Illinois Press, 1999. (originally published in 1975) ISBN 0-252-06829-7

- Kalin, Tom (director), Swoon. Film, 1990

- Levin, Meyer. Compulsion, Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1996. (originally published in 1956). ISBN 0-7867-0319-9

- Logan, John (author), Never the Sinner (play), Samuel French, Inc., 1987

- Saul, John (author). In the Dark of the Night, 2006 ISBN 0-345-48701-X

- Dolginoff, Stephen (author/composer). Thrill Me: The Leopold & Loeb Story (musical, published by Dramatists Play Service) ISBN 0-8222-2102-0

- Galluzzo, Mark Anthony (director). R.S.V.P. Film, 2002

- Vonnegut, Kurt (author). "Jailbird" (page 171) Published by Delacorte Press/Seymour Lawrence ISBN 0-440-05449-4

- The Sopranos (Season 1, Episode 7) TV series distributed by HBO Pictures

- "Yesterday" (Season 1, Episode 18), Law & Order: Criminal Intent. By Rene Balcer and Theresa Rebeck. Performed by Vincent D'Onofrio, Kathryn Erbe, Jamey Sheridan, Courtney B. Vance, Jim True-Frost, Danton Stone. NBC. WNBC, New York City. April 14, 2002

- Morita, Yoshimitsu (director). Copycat Killer. Film, 2002

- Leopold, N.F. 1963. Checklist of the Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras.

- "Boardwalk Empire" (Season 4, Episode 7) TV series distributed by HBO Pictures

External links

- Leopold and Loeb Trial Home Page by Douglas Linder. Famous American Trials — Illinois v. Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb. University of Missouri at Kansas City Law School. 1997. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, Crime of the 20th Century by Marilyn Bardsley. Crime Library — Courtroom Television Network. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- Northwestern University Archives

- leopoldandloeb.com

- Thrill Me:The Leopold and Loeb Story - main site/CD ordering

- Thrill Me:The Leopold and Loeb Story Review quotes from York Theatre Company

- Harold S. Hulbert Papers from Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois

- "Leopold and Loeb Collection" from Northwestern University Special Collections, Evanston, Illinois

- Charles DeLacy (August 1930). "Inside Facts on the Leopold-Loeb Crime". True Detective Mysteries. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- The Loeb-Leopold case : with excerpts from the evidence of the alienists and including the arguments to the court by counsel for the people and the defense (1926) stored on Archive.org