Logistic function

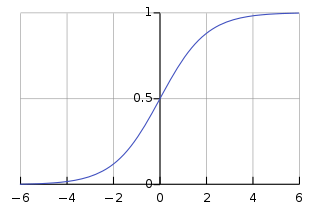

A logistic function or logistic curve is a common "S" shape (sigmoid curve), with equation:

where

- e = the natural logarithm base (also known as Euler's number),

- x0 = the x-value of the sigmoid's midpoint,

- L = the curve's maximum value, and

- k = the steepness of the curve.[1]

For values of x in the range of real numbers from −∞ to +∞, the S-curve shown on the right is obtained (with the graph of f approaching L as x approaches +∞ and approaching zero as x approaches −∞).

The function was named in 1844–1845 by Pierre François Verhulst, who studied it in relation to population growth.[2] The initial stage of growth is approximately exponential; then, as saturation begins, the growth slows, and at maturity, growth stops.

The logistic function finds applications in a range of fields, including artificial neural networks, biology (especially ecology), biomathematics, chemistry, demography, economics, geoscience, mathematical psychology, probability, sociology, political science, and statistics.

Mathematical properties

The standard logistic function is the logistic function with parameters (k = 1, x0 = 0, L = 1) which yields

.

In practice, due to the nature of the exponential function e−x, it is often sufficient to compute the standard logistic function for x over a small range of real numbers such as a range contained in [−6, +6].

Derivative

The standard logistic function has an easily calculated derivative:

- .

It also has the property that

- .

Thus, is an odd function.

Logistic differential equation

The standard logistic function is the solution of the simple first-order non-linear ordinary differential equation

with boundary condition f(0) = 1/2. This equation is the continuous version of the logistic map.

The qualitative behavior is easily understood in terms of the phase line: the derivative is null when function is unit and the derivative is positive for f between 0 and 1, and negative for f above 1 or less than 0 (though negative populations do not generally accord with a physical model). This yields an unstable equilibrium at 0, and a stable equilibrium at 1, and thus for any function value greater than zero and less than unit, it grows to unit.

The above equation can be rewritten in the following steps:

Which is a special case of the Bernoulli differential equation and has the following solution:

Choosing the constant of integration gives the other well-known form of the definition of the logistic curve

More quantitatively, as can be seen from the analytical solution, the logistic curve shows early exponential growth for negative argument, which slows to linear growth of slope 1/4 for an argument near zero, then approaches one with an exponentially decaying gap.

The logistic function is the inverse of the natural logit function and so can be used to convert the logarithm of odds into a probability. In mathematical notation the logistic function is sometimes written as expit[3] in the same form as logit. The conversion from the log-likelihood ratio of two alternatives also takes the form of a logistic curve.

The logistic sigmoid function is related to the hyperbolic tangent, A.p. by

or

- .

The latter relationship follows from

The hyperbolic tangent relationship leads to another form for the logistic function's derivative:

- ,

which ties the logistic function into the Logistic distribution.

Applications

In ecology: modeling population growth

A typical application of the logistic equation is a common model of population growth (see also population dynamics), originally due to Pierre-François Verhulst in 1838, where the rate of reproduction is proportional to both the existing population and the amount of available resources, all else being equal. The Verhulst equation was published after Verhulst had read Thomas Malthus' An Essay on the Principle of Population. Verhulst derived his logistic equation to describe the self-limiting growth of a biological population. The equation was rediscovered in 1911 by A. G. McKendrick for the growth of bacteria in broth and experimentally tested using a technique for nonlinear parameter estimation.[4] The equation is also sometimes called the Verhulst-Pearl equation following its rediscovery in 1920 by Raymond Pearl (1879–1940) and Lowell Reed (1888–1966) of the Johns Hopkins University.[5] Another scientist, Alfred J. Lotka derived the equation again in 1925, calling it the law of population growth.

Letting P represent population size (N is often used in ecology instead) and t represent time, this model is formalized by the differential equation:

where the constant r defines the growth rate and K is the carrying capacity.

In the equation, the early, unimpeded growth rate is modeled by the first term +rP. The value of the rate r represents the proportional increase of the population P in one unit of time. Later, as the population grows, the modulus of the second term (which multiplied out is −rP2/K) becomes almost as large the first as some members of the population P interfere with each other by competing for some critical resource, such as food or living space. This antagonistic effect is called the bottleneck, and is modeled by the value of the parameter K. The competition diminishes the combined growth rate, until the value of P ceases to grow (this is called maturity of the population). The solution to the equation (with being the initial population) is

where

- .

Which is to say that K is the limiting value of P: the highest value that the population can reach given infinite time (or come close to reaching in finite time). It is important to stress that the carrying capacity is asymptotically reached independently of the initial value P(0) > 0, also in case that P(0) > K.

In ecology, species are sometimes referred to as r-strategist or K-strategist depending upon the selective processes that have shaped their life history strategies. Choosing the variable dimensions so that n measures the population in units of carrying capacity, and τ measures time in units of 1/r, gives the dimensionless differential equation

- .

Time-varying carrying capacity

Since the environmental conditions influence the carrying capacity, as a consequence it can be time-varying: K(t) > 0, leading to the following mathematical model:

A particularly important case is that of carrying capacity that varies periodically with period T:

- .

It can be shown that in such a case, independently from the initial value P(0) > 0, P(t) will tend to a unique periodic solution P*(t), whose period is T.

A typical value of T is one year: In such case K(t) may reflect periodical variations of weather conditions.

Another interesting generalization is to consider that the carrying capacity K(t) is a function of the population at an earlier time, capturing a delay in the way population modifies its environment. This leads to a logistic delay equation,[6] which has a very rich behavior, with bistability in some parameter range, as well as a monotonic decay to zero, smooth exponential growth, punctuated unlimited growth (i.e., multiple S-shapes), punctuated growth or alternation to a stationary level, oscillatory approach to a stationary level, sustainable oscillations, finite-time singularities as well as finite-time death.

In statistics and machine learning

Logistic functions are used in several roles in statistics. For example, they are the cumulative distribution function of the logistic family of distributions, and they are, a bit simplified, used to model the chance a chess player has to beat his opponent in the Elo rating system. More specific examples now follow.

Logistic regression

Logistic functions are used in logistic regression to model how the probability p of an event may be affected by one or more explanatory variables: an example would be to have the model

where x is the explanatory variable and a and b are model parameters to be fitted.

Logistic regression and other log-linear models are also commonly used in machine learning. A generalisation of the logistic function to multiple inputs is the softmax activation function, used in multinomial logistic regression.

Another of the logistic function is in the Rasch model, used in item response theory. In particular, the Rasch model forms a basis for maximum likelihood estimation of the locations of objects or persons on a continuum, based on collections of categorical data, for example the abilities of persons on a continuum based on responses that have been categorized as correct and incorrect.

Neural networks

Logistic functions are often used in neural networks to introduce nonlinearity in the model and/or to clamp signals to within a specified range. A popular neural net element computes a linear combination of its input signals, and applies a bounded logistic function to the result; this model can be seen as a "smoothed" variant of the classical threshold neuron.

A common choice for the activation or "squashing" functions, used to clip for large magnitudes to keep the response of the neural network bounded[7] is

which is a logistic function. These relationships result in simplified implementations of artificial neural networks with artificial neurons. Practitioners caution that sigmoidal functions which are antisymmetric about the origin (e.g. the hyperbolic tangent) lead to faster convergence when training networks with backpropagation.[8]

The logistic function is itself the derivative of another proposed activation function, the softplus.

In medicine: modeling of growth of tumors

Another application of logistic curve is in medicine, where the logistic differential equation is used to model the growth of tumors. This application can be considered an extension of the above-mentioned use in the framework of ecology (see also the Generalized logistic curve, allowing for more parameters). Denoting with X(t) the size of the tumor at time t, its dynamics are governed by:

which is of the type:

where F(X) is the proliferation rate of the tumor.

If a chemotherapy is started with a log-kill effect, the equation may be revised to be

- ,

where c(t) is the therapy-induced death rate. In the idealized case of very long therapy, c(t) can be modeled as a periodic function (of period T) or (in case of continuous infusion therapy) as a constant function, and one has that

i.e. if the average therapy-induced death rate is greater than the baseline proliferation rate then there is the eradication of the disease. Of course, this is an oversimplified model of both the growth and the therapy (e.g. it does not take into account the phenomenon of clonal resistance).

In chemistry: reaction models

The concentration of reactants and products in autocatalytic reactions follow the logistic function.

In physics: Fermi distribution

The logistic function determines the statistical distribution of fermions over the energy states of a system in thermal equilibrium. In particular, it is the distribution of the probabilities that each possible energy level is occupied by a fermion, according to Fermi–Dirac statistics.

In linguistics: language change

In linguistics, the logistic function can be used to model language change:[9] an innovation that is at first marginal begins to spread more quickly with time, and then more slowly as it becomes more universally adopted.

In economics and sociology: diffusion of innovations

The logistic function can be used to illustrate the progress of the diffusion of an innovation through its life cycle.

In The Laws of Imitation (1890), Gabriel Tarde describes the rise and spread of new ideas through imitative chains. In particular, Tarde identifies three main stages through which innovations spread: the first one corresponds to the difficult beginnings, during which the idea has to struggle within a hostile environment full of opposing habits and beliefs; the second one corresponds to the properly exponential take-off of the idea, with ; finally, the third stage is logarithmic, with , and corresponds to the time when the impulse of the idea gradually slows down while, simultaneously new opponent ideas appear. The ensuing situation halts or stabilizes the progress of the innovation, which approaches an asymptote.

In the history of economy, when new products are introduced there is an intense amount of research and development which leads to dramatic improvements in quality and reductions in cost. This leads to a period of rapid industry growth. Some of the more famous examples are: railroads, incandescent light bulbs, electrification, cars and air travel. Eventually, dramatic improvement and cost reduction opportunities are exhausted, the product or process are in widespread use with few remaining potential new customers, and markets become saturated.

Logistic analysis was used in papers by several researchers at the International Institute of Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). These papers deal with the diffusion of various innovations, infrastructures and energy source substitutions and the role of work in the economy as well as with the long economic cycle. Long economic cycles were investigated by Robert Ayres (1989).[10] Cesare Marchetti published on long economic cycles and on diffusion of innovations.[11][12] Arnulf Grübler’s book (1990) gives a detailed account of the diffusion of infrastructures including canals, railroads, highways and airlines, showing that their diffusion followed logistic shaped curves.[13]

Carlota Perez used a logistic curve to illustrate the long (Kondratiev) business cycle with the following labels: beginning of a technological era as irruption, the ascent as frenzy, the rapid build out as synergy and the completion as maturity.[14]

See also

- Diffusion of innovations

- Generalised logistic curve

- Gompertz curve

- Heaviside step function

- Hubbert curve

- Logistic distribution

- Logistic map

- Logistic regression

- Logistic smooth-transmission model

- Logit

- Log-likelihood ratio

- Malthusian growth model

- Population dynamics

- r/K selection theory

- Shifted Gompertz distribution

- Tipping point (sociology)

- Rectifier (neural networks)

Notes

- ^ Verhulst, Pierre-François (1838). "Notice sur la loi que la population poursuit dans son accroissement" (PDF). Correspondance mathématique et physique. 10: 113–121. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Verhulst, Pierre-François (1845). "Recherches mathématiques sur la loi d'accroissement de la population". Nouveaux Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres de Bruxelles. 18: 1–42. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ expit documentation for R's clusterPower package

- ^ A. G. McKendricka; M. Kesava Paia1 (January 1912). "XLV.—The Rate of Multiplication of Micro-organisms: A Mathematical Study". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 31: 649–653. doi:10.1017/S0370164600025426.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Raymond Pearl and Lowell Reed (June 1920). "On the Rate of Growth of the Population of the United States" (PDF). Proc. of the National Academy of Sciences. Vol. 6, no. 6. p. 275.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Yukalov, V. I.; Yukalova, E. P.; Sornette, D. (2009). "Punctuated evolution due to delayed carrying capacity". Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 238 (17): 1752. doi:10.1016/j.physd.2009.05.011.

- ^ Gershenfeld 1999, p.150

- ^ LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Orr, G.; Muller, K. (1998). Orr, G.; Muller, K. (eds.). Efficient BackProp (PDF). Springer. ISBN 3-540-65311-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Bod, Hay, Jennedy (eds.) 2003, pp. 147–156

- ^ Ayres, Robert (1989). "Technological Transformations and Long Waves" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Marchetti, Cesare (1996). "Pervasive Long Waves: Is Society Cyclotymic" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Marchetti, Cesare (1988). "Kondratiev Revisited-After One Cycle" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Grübler, Arnulf (1990). The Rise and Fall of Infrastructures: Dynamics of Evolution and Technological Change in Transport (PDF). Heidelberg and New York: Physica-Verlag.

- ^ Perez, Carlota (2002). Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84376-331-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

References

- Jannedy, Stefanie; Bod, Rens; Hay, Jennifer (2003). Probabilistic Linguistics. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-52338-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gershenfeld, Neil A. (1999). The Nature of Mathematical Modeling. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57095-4.

- Kingsland, Sharon E. (1995). Modeling nature: episodes in the history of population ecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-43728-0.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Logistic Equation". MathWorld.