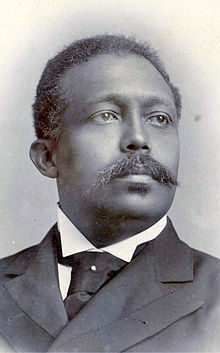

Luis Antonio Robles

Luis Antonio Robles | |

|---|---|

Oil painting by Epifanio Julián Garay y Caicedo. | |

| Member of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia | |

| In office 1 April 1892 – 1 April 1896 | |

| Constituency | Antioquia State |

| In office 1 March 1876 – 1 April 1876 | |

| Constituency | Magdalena State |

| 16th President of the Sovereign State of Magdalena | |

| In office 1 April 1878 – 25 June 1879 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Davila García |

| Succeeded by | José María Campo Serrano |

| Colombian Secretary of the Treasury and Public Credit | |

| In office 1 April 1876 – 1 April 1877 | |

| President | Aquileo Parra Gómez |

| Preceded by | José María Villamizar Gallardo |

| Succeeded by | José María Quijano Wallis |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Luis Antonio Robles Suárez 24 October 1849 Riohacha, Riohacha, Magdalena, New Granada |

| Died | 22 September 1899 (aged 49) Bogotá, Cundinamarca, Colombia |

| Nationality | Colombian |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Alma mater | Our Lady of the Rosary University (JD) |

| Profession | Lawyer |

Luis Antonio Robles Suárez (24 October 1849 – 22 September 1899)[1][2] also known as "El Negro Robles", was a Colombian lawyer and politician. He was the first Afro-Colombian to hold a cabinet-level ministry in Colombia serving as Secretary of the Treasury and Public Credit during the administration of President Aquileo Parra Gómez, as well as being the first Afro-Colombian Congressperson as Member of the Chamber of Representatives for Magdalena, and the first Afro-Colombian Governor of a Department, as the 16th President of the Sovereign State of Magdalena.[3] He graduated a lawyer from Our Lady of the Rosary University in 1872, thus also becoming the first Afro-Colombian to ever serve as a lawyer in Colombia.[4][5]

Career[edit]

It is not my fault that I am Black: Night has imprinted her mantle over my epidermis. But the bones of my ancestors in the vaults of Cartagena still whiten, for giving freedom to many Whites of black consciences such as yours.

— Luis Antonio Robles, [4]

I won't be silenced! I have the right to speak as a representative of the people. Yes, I belong the Black race, redeemed by the Republic, and my duty is to serve those who shattered its yoke.

— Luis Antonio Robles, [3]

Personal life[edit]

Born on 24 October 1849 in the hamlet of Camarones in the Municipality of Riohacha, then part of the Riohacha Province, in the Department of Magdalena, New Granada; his parents were Luis Antonio Robles and Manuela Súarez, both black freedpersons of moderate means.[1]

He died on 22 September 1899 of cystitis infection in his longtime residence le Maison Doré in Bogotá at the age of 49,[2][6] not having married and with no descendants still recovering from the death of his mother earlier that year.[3] His childhood home in Camarones was designated a national monument, and his remains, which had been interred at the Central Cemetery of Bogotá,[2] were transported to be interred at his childhood home which operates as a Cultural House, Library and Training Center.[5][7]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Arriaga Copete, Libardo (2002). Cátedra de estudios afrocolombianos: nociones elementales y hechos históricos que se deben conocer para el desarrollo de la Cátedra de Estudios Afrocolombianos, o lo que todos debemos saber sobre los negros [Afro-Colombian Studies: basic concepts and historical facts to be known for the development of the Afro-Colombian Studies, or what we should all know about blacks] (in Spanish). Igasa- Ingenieros Graficos Andinos. p. 176. ISBN 978-958-33-3817-5.

- ^ a b c "Acuerdo 47 de 1916" [Accord 47 of 1916] (in Spanish). Bogotá: City Council. 1916-10-10. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ a b c Romero Jaramillo, Dolcey (August 1994). "Presidentes de los 9 Estados Soberanos" [Presidents of the 9 Sovereign States]. Revista Credencial Historia (in Spanish) (56). Bogotá: Luis Ángel Arango Library. OCLC 71823382. Archived from the original on 2012-12-05. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ a b Carrascal, María Fernanda (2010). "Luis Antonio Robles: El primer colegial negro" [Luis Antonio Robles: The First Black Alumnus] (PDF). Nova et Vetera (in Spanish) (4). Bogotá: Our Lady of the Rosary University: 8. ISSN 1542-7315. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ a b "Declaratoria de un nuevo Bien de Interés Cultural e inclusión de otro en la Lista Indicativa de Candidatos a Bienes de Interés Cultural en el Ámbito Nacional" [Declaration of a new Cultural Property and inclusion of another in the tentative List of Candidates for Cultural Interest at the National level] (in Spanish). Ministry of Culture. 2010-05-18. Archived from the original on 2012-11-30. Retrieved 2011-04-24.

- ^ Gómez Naranjo, Pedro Alejandro (1963). La sal de la historia [The Salt of History] (in Spanish). Bucaramanga: Departamental Press. OCLC 4934098.

- ^ Carrillo Pérez, Idayris Yolima; Cotes Mejía, Micael Segundo (2000-02-07). Ley 570 de 2000 [Law 570 of 2000] (in Spanish). Bogotá: Diario Oficial, Congress of Colombia. ISSN 1657-6241. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- "Por medio de la cual se honra la memoria de un ilustre colombiano (Luis Antonio Robles)". Congreso Visible (in Spanish). 1999-08-10.

Further reading[edit]

- Acosta Medina, Amilkar David; Knudsen Quevedo, Hans-Peter; Nieto Arango, Luis Enrique; Pérez Escobar, Jacobo; Prado Mosquera, Diana Carolina; Rodríguez, Gloria Amparo (November 2010). Luis A. Robles: Sombra y Luz [Luis A. Robles: Shadow and Light] (in Spanish). Bogotá: Our Lady of the Rosary University, Faculty of Jurisprudence. ISBN 978-958-738-148-1.

- González Zubiría, Fredy (2007). Luis Antonio Robles: El Paladín de la Democracia [Luis Antonio Robles: The Paladin of Democracy] (in Spanish). Riohacha: Government of La Guajira.

- Pérez Escobar, Jacobo (1999). El Negro Robles y Su Época [Negro Robles and His Time] (in Spanish). Bogotá: Centro para la Investigación de la Cultura Negra. OCLC 45163117.

- Rodríguez Pimienta, José Manuel (1995). El Negro Robles: Comentarios Sobre la Vida lel Orador Radical [Negro Robles: Commentaries on the Life of the Radical Orator] (in Spanish). Santa Marta: University of Magdalena. OCLC 36803638.

External links[edit]

- Colectivo Audiovisual Pimentón Rojo. "El Caribe en el Bicentenario: Luis Antonio Robles" [The Caribbean in the Bicentenary] (YouTube video). Bicentenary of the Independence of Colombia (in Spanish). Telecaribe.

- 1849 births

- 1899 deaths

- People from La Guajira Department

- Del Rosario University alumni

- Academic staff of the Free University of Colombia

- 19th-century Colombian lawyers

- Colombian Liberal Party politicians

- Members of the Chamber of Representatives of Colombia

- Members of the Senate of Colombia

- Colombian Secretaries of Treasury and Public Credit

- Colombian people of African descent