Microeconomics

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

Microeconomics (from Greek prefix mikro- meaning "small" and economics) is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and small impacting organizations in making decisions on the allocation of limited resources (see scarcity).[1] Typically, it applies to markets where goods or services are bought and sold. Microeconomics examines how these decisions and behaviors affect the supply and demand for goods and services, which determines prices, and how prices, in turn, determine the quantity supplied and quantity demanded of goods and services.[2][3]

This is in contrast to macroeconomics, which involves the "sum total of economic activity, dealing with the issues of growth, inflation, and unemployment."[2] Microeconomics also deals with the effects of national economic policies (such as changing taxation levels) on the aforementioned aspects of the economy.[4] Particularly in the wake of the Lucas critique, much of modern macroeconomic theory has been built upon 'microfoundations'—i.e. based upon basic assumptions about micro-level behavior.[5]

One of the goals of microeconomics is to analyze market mechanisms that establish relative prices amongst goods and services and allocation of limited resources amongst many alternative uses. Microeconomics analyzes market failure, where markets fail to produce efficient results, and describes the theoretical conditions needed for perfect competition. Significant fields of study in microeconomics include general equilibrium, markets under asymmetric information, choice under uncertainty and economic applications of game theory. Also considered is the elasticity of products within the market system.

Assumptions and definitions

The fundamentals of Microeconomics lies in the analysis of the preference relations. Preference relations are defined simply to be a set of different choices that an actor can choose (a k-cell metric space) that actors can also compare between any two bundles of choices ( completeness of the relationship.) In order to analyze the problem further, the assumption of transitivity is added to the mix. These two assumptions of completeness and transitivity that are imposed upon the preference relations are what is termed rationality. Microeconomic analysis are conducted mainly through imposition of additional constraints on the preference relations or even relaxation of the above stated assumptions (most often transitivity) although such relaxation makes the problem much harder to analyze.

The theory of supply and demand usually assumes that markets are perfectly competitive. This implies that there are many buyers and sellers in the market and none of them have the capacity to significantly influence prices of goods and services. In many real-life transactions, the assumption fails because some individual buyers or sellers have the ability to influence prices. Quite often, a sophisticated analysis is required to understand the demand-supply equation of a good model. However, the theory works well in situations meeting these assumptions.

Mainstream economics does not assume a priori that markets are preferable to other forms of social organization. In fact, much analysis is devoted to cases where so-called market failures lead to resource allocation that is suboptimal by some standard (defense spending is the classic example, profitable to all for use but not directly profitable for anyone to finance). In such cases, economists may attempt to find policies that avoid waste, either directly by government control, indirectly by regulation that induces market participants to act in a manner consistent with optimal welfare, or by creating "missing markets" to enable efficient trading where none had previously existed.

This is studied in the field of collective action and public choice theory. "Optimal welfare" usually takes on a Paretian norm, which in its mathematical application of Kaldor–Hicks method. This can diverge from the Utilitarian goal of maximizing utility because it does not consider the distribution of goods between people. Market failure in positive economics (microeconomics) is limited in implications without mixing the belief of the economist and their theory.

The demand for various commodities by individuals is generally thought of as the outcome of a utility-maximizing process, with each individual trying to maximize their own utility under a budget constraint and a given consumption set.

Microeconomic topics

The study of microeconomics involves several "key" areas:

Demand, supply, and equilibrium

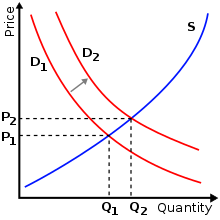

Supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It concludes that in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded by consumers will equal the quantity supplied by producers resulting in an economic equilibrium for price and quantity.

Measurement of elasticities

Elasticity is the measurement of how responsive an economic variable is to a change in another variable. Elasticity can be quantified as the ratio of the percentage change in one variable to the percentage change in another variable, when the latter variable has a causal influence on the former. It is a tool for measuring the responsiveness of a variable, or of the function that determines it, to changes in causative variables in unitless ways. Frequently used elasticities include price elasticity of demand, price elasticity of supply, income elasticity of demand, elasticity of substitution between factors of production and elasticity of intertemporal substitution.

Consumer demand theory

Consumer demand theory relates preferences for the consumption of both goods and services to the consumption expenditures; ultimately, this relationship between preferences and consumption expenditures is used to relate preferences to consumer demand curves. The link between personal preferences, consumption and the demand curve is one of the most closely studied relations in economics. It is a way of analyzing how consumers may achieve equilibrium between preferences and expenditures by maximizing utility subject to consumer budget constraints.

Theory of production

Production theory is the study of production, or the economic process of converting inputs into outputs. Production uses resources to create a good or service that is suitable for use, gift-giving in a gift economy, or exchange in a market economy. This can include manufacturing, storing, shipping, and packaging. Some economists define production broadly as all economic activity other than consumption. They see every commercial activity other than the final purchase as some form of production.

Costs of production

The cost-of-production theory of value is the price of an object or condition is determined by the sum of the cost of the resources that went into making it. The cost can comprise any of the factors of production: labour, capital, land. Technology can be viewed either as a form of fixed capital (ex:plant) or circulating capital (ex:intermediate goods).

Perfect competition

Perfect competition describes markets such that no participants are large enough to have the market power to set the price of a homogeneous product. An example is Ebay.

Perfect monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek monos μόνος (alone or single) + polein πωλεῖν (to sell)) exists when a single company is the only supplier of a particular commodity.

Oligopoly

An oligopoly is a market form in which a market or industry is dominated by a small number of sellers (oligopolists). Oligopolies can result from various forms of collusion which reduce competition and lead to higher costs for consumers.[6]

Market structure

The market structure can have several types of interacting market systems. Different forms of markets is a feature of capitalism and advocates of socialism often criticize markets and aim to substitute markets with economic planning to varying degrees. Competition is the regulatory mechanism of the market system.

- Monopolistic competition, also called competitive market, where there is a large number of firms, each having a small proportion of the market share and slightly differentiated products.

- Oligopoly, in which a market is run by a small number of firms that together control the majority of the market share.

- Duopoly, a special case of an oligopoly with two firms.

- Monopsony, when there is only one buyer in a market.

- Oligopsony, a market where many sellers can be present but meet only a few buyers.

- Monopoly, where there is only one provider of a product or service.

- Natural monopoly, a monopoly in which economies of scale cause efficiency to increase continuously with the size of the firm. A firm is a natural monopoly if it is able to serve the entire market demand at a lower cost than any combination of two or more smaller, more specialized firms.

- Perfect competition, a theoretical market structure that features no barriers to entry, an unlimited number of producers and consumers, and a perfectly elastic demand curve.

Examples of markets include but are not limited to: commodity markets, insurance markets, bond markets, energy markets, flea markets, debt markets, stock markets, online auctions, media exchange markets, real estate market.

Game theory

Game theory is a major method used in mathematical economics and business for modeling competing behaviors of interacting agents. Applications include a wide array of economic phenomena and approaches, such as auctions, bargaining, mergers & acquisitions pricing, fair division, duopolies, oligopolies, social network formation, agent-based computational economics, general equilibrium, mechanism design,and voting systems, and across such broad areas as experimental economics, behavioral economics, information economics, industrial organization, and political economy.

Labour economics

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the markets for wage labour. Labour markets function through the interaction of workers and employers. Labour economics looks at the suppliers of labour services (workers), the demands of labour services (employers), and attempts to understand the resulting pattern of wages, employment, and income. In economics, labour is a measure of the work done by human beings. It is conventionally contrasted with such other factors of production as land and capital. There are theories which have developed a concept called human capital (referring to the skills that workers possess, not necessarily their actual work), although there are also counter posing macro-economic system theories that think human capital is a contradiction in terms.

Welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to evaluate well-being from allocation of productive factors as to desirability and economic efficiency within an economy, often relative to competitive general equilibrium.[7] It analyzes social welfare, however measured, in terms of economic activities of the individuals that compose the theoretical society considered. Accordingly, individuals, with associated economic activities, are the basic units for aggregating to social welfare, whether of a group, a community, or a society, and there is no "social welfare" apart from the "welfare" associated with its individual units.

Economics of information

Information economics or the economics of information is a branch of microeconomic theory that studies how information and information systems affect an economy and economic decisions. Information has special characteristics. It is easy to create but hard to trust. It is easy to spread but hard to control. It influences many decisions. These special characteristics (as compared with other types of goods) complicate many standard economic theories.[8]

Opportunity cost

Opportunity cost of an activity (or goods) is equal to the best next alternative uses/foregone. Although opportunity cost can be hard to quantify, the effect of opportunity cost is universal and very real on the individual level. In fact, this principle applies to all decisions, not just economic ones.

Opportunity cost is one way to measure the cost of something. Rather than merely identifying and adding the costs of a project, one may also identify the next best alternative way to spend the same amount of money. The forgone profit of this next best alternative is the opportunity cost of the original choice. A common example is a farmer that chooses to farm their land rather than rent it to neighbors, wherein the opportunity cost is the forgone profit from renting. In this case, the farmer may expect to generate more profit alone. This kind of reasoning is a very important part of the calculation of discount rates in discounted cash flow investment valuation methodologies. Similarly, the opportunity cost of attending university is the lost wages a student could have earned in the workforce, rather than the cost of tuition, books, and other requisite items (whose sum makes up the total cost of attendance).

Note that opportunity cost is not the sum of the available alternatives, but rather the benefit of the single, best alternative. Possible opportunity costs of a city's decision to build a hospital on its vacant land are the loss of the land for a sporting center, or the inability to use the land for a parking lot, or the money that could have been made from selling the land, or the loss of any of the various other possible uses — but not all of these in aggregate. The true opportunity cost would be the forgone profit of the most lucrative of those listed.

One question that arises here is how to determine a money value for each alternative to facilitate comparison and assess opportunity cost, which may be more or less difficult depending on the things we are trying to compare. For example, many decisions involve environmental impacts whose monetary value is difficult to assess because of scientific uncertainty. Valuing a human life or the economic impact of an Arctic oil spill involves making subjective choices with ethical implications.

It is imperative to understand that no decision on allocating time is free. No matter what one chooses to do, they are always giving something up in return. An example of opportunity cost is deciding between going to a concert and doing homework. If one decides to go the concert, then they are giving up valuable time to study, but if they choose to do homework then the cost is giving up the concert. Any decision in allocating capital is likewise: there is an opportunity cost of capital, or a hurdle rate, defined as the expected rate one could get by investing in similar projects on the open market. Opportunity cost is vital in understanding microeconomics and decisions that are made.

Applied microeconomics

Applied microeconomics includes a range of specialized areas of study, many of which draw on methods from other fields. Industrial organization examines topics such as the entry and exit of firms, innovation, and the role of trademarks. Labor economics examines wages, employment, and labor market dynamics. Financial economics examines topics such as the structure of optimal portfolios, the rate of return to capital, econometric analysis of security returns, and corporate financial behavior. Public economics examines the design of government tax and expenditure policies and economic effects of these policies (e.g., social insurance programs). Political economy examines the role of political institutions in determining policy outcomes. Health economics examines the organization of health care systems, including the role of the health care workforce and health insurance programs. Urban economics, which examines the challenges faced by cities, such as sprawl, air and water pollution, traffic congestion, and poverty, draws on the fields of urban geography and sociology. Law and economics applies microeconomic principles to the selection and enforcement of competing legal regimes and their relative efficiencies. Economic history examines the evolution of the economy and economic institutions, using methods and techniques from the fields of economics, history, geography, sociology, psychology, and political science.

Development

Traditional marginalism

The modern field of microeconomics arose as an effort of neoclassical economics school of thought to put economic ideas into mathematical mode. An early attempt was made by Antoine Augustine Cournot in Researches on the Mathematical Principles of the Theory of Wealth[9] (1838) in describing a spring water duopoly that now bears his name. Later, William Stanley Jevons's Theory of Political Economy[10] (1871), Carl Menger's Principles of Economics[11] (1871), and Léon Walras's Elements of Pure Economics: Or the theory of social wealth (1874–77)[12] gave way to what was called the Marginal Revolution. Some common ideas behind those works were models or arguments characterized by rational economic agents maximizing utility under a budget constrain. This arose as a necessity of arguing against the labour theory of value associated with classical economists such as Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx. Walras also went as far as developing the concept of general equilibrium of an economy.

Alfred Marshall's textbook, Principles of Economics[13] was published in 1890 and became the dominant textbook in England for a generation. His main point was that Jevons went too far in emphasizing utility as an attempt to explain prices over costs of production. In the book he writes:

"There are few writers of modern times who have approached as near to the brilliant originality of Ricardo as Jevons has done. But he appears to have judged both Ricardo and Mill harshly, and to have attributed to them doctrines narrower and less scientific than those they really held. Also, his desire to emphasize an aspect of value to which they had given insufficient prominence, was probably in some measure accountable for his saying, "Repeated reflection and inquiry have led me to the somewhat novel opinion that value depends entirely upon utility." (Theory, p. 1) This statement seems to be no less one-sided and fragmentary, and much more misleading, than that into which Ricardo often glided with careless brevity, as to the dependence of value on cost of production; but which he never regarded as more than a part of a larger doctrine, the rest of which he had tried to explain. "

In the same appendix[14] he further states:

"Perhaps Jevons' antagonism to Ricardo and Mill would have been less if he had not himself fallen into the habit of speaking of relations which really exist only between demand price and value as though they held between utility and value; and if he had emphasized as Cournot had done, and as the use of mathematical forms might have been expected to lead him to do, that fundamental symmetry of the general relations in which demand and supply stand to value, which coexists with striking differences in the details of those relations. We must not indeed forget that, at the time at which he wrote, the demand side of the theory of value had been much neglected; and that he did excellent service by calling attention to it and developing it. There are few thinkers whose claims on our gratitude are as high and as various as those of Jevons: but that must not lead us to accept hastily his criticisms on his great predecessors."

Marshall's idea of solving the controversy was that the demand curve could be derived by aggregating individual consumer demand curves, which were themselves based on the consumer problem of maximizing utility. The supply curve could be derived by superimposing a representative firm supply curves for the factors of production and then market equilibrium would be given by the intersection of demand and supply curves. He also introduced the notion of different market periods: mainly short run and long run. This set of ideas gave way to what economists call perfect competition, now found in the standard microeconomics texts, even though Marshall himself had stated:[15]

"The process of substitution, of which we have been discussing the tendencies, is one form of competition; and it may be well to insist again that we do not assume that competition is perfect. Perfect competition requires a perfect knowledge of the state of the market; and though no great departure from the actual facts of life is involved in assuming this knowledge on the part of dealers when we are considering the course of business in Lombard Street, the Stock Exchange, or in a wholesale Produce Market; it would be an altogether unreasonable assumption to make when we are examining the causes that govern the supply of labour in any of the lower grades of industry. For if a man had sufficient ability to know everything about the market for his labour, he would have too much to remain long in a low grade. The older economists, in constant contact as they were with the actual facts of business life, must have known this well enough; but partly for brevity and simplicity, partly because the term "free competition" had become almost a catchword, partly because they had not sufficiently classified and conditioned their doctrines, they often seemed to imply that they did assume this perfect knowledge. "

An early formulation of the concept of production functions is due to Johann Heinrich von Thünen,[16] which presented an exponential version of it. The standard Cobb–Douglas production function found in microeconomics textbooks refers to a collaborative paper between Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas published in 1928 in which they analyzed U.S. manufacturing data using this function as the basis of a regression analysis for estimating the relationship between inputs (labour and capital) and output (product):[17] this discussion takes place through the concept of marginal productivity. The mathematical form of the Cobb–Douglas function can be found in the prior work of Wicksell, Thünen, and Turgot.

Jacob Viner presented an early procedure for constructing cost curves in his “Cost Curves and Supply Curves” (1931),[18] the paper was an attempt to reconcile two streams of thought when dealing with this issue at the time: the idea that supplies of factors of production were given and independent of rate of remuneration (Austrian School) or dependent on rate of remuneration (English School, that is followers of Marshall). Viner argued that, “The differences between the two schools would not affect qualitatively the character of the findings,” more specifically, “...that this concern is not of sufficient importance to bring about any change in the prices of the factors as a result of a change in its output.”

In Viner's terminology—now considered standard—the short run is a period long enough to permit any desired output change that is technologically possible without altering the scale of the plant—but is not long enough to adjust the scale of the plant. He arbitrarily assumes that all factors can, for the short run, be classified in two groups: those necessarily fixed in amount, and those freely variable. Scale of plant is the size of the group of factors that are fixed in amount in the short-run, and each scale is quantitatively indicated by the amount of output that can be produced at the lowest average cost possible at that scale. Costs associated with the fixed factors are fixed costs. Those associated with the variable factors are direct costs. Note that fixed costs are fixed only in their aggregate amounts, and vary with output in their amount per unit, while direct costs vary in their aggregate amount as output varies, as well as in their amount per unit. The spreading of overhead is therefore a short-run phenomenon and not to be confused with the long-run.

He explains that if the law of diminishing returns holds that output per unit of variable factor falls as total output rises, and that if the prices of the factors remain constant—then average direct costs increase with output. Also, if atomistic competition prevails—that is, the individual firm output won't affect product prices—then the individual firm short-run supply curve equals the short run marginal cost curve. In the long run, the supply curve for industry can be constructed by summing individual marginal cost curves abscissas. He also explains that:

- Internal economies of scale are primarily a long-run phenomenon and are due either to reductions in the technical coefficients of production (technical economies=increasing productivity by improved organization or methods of production) or to discounts resulting from larger size (pecuniary economies).

- Internal diseconomies of scale can be avoided by increasing industry output by increasing the number of plants without increasing the scale of the plant.

- External economies of scale are also either technical or pecunary, but in this case are due to the aggregate behavior of the industry, and refer to the size of output of the industry as a whole.

- External diseconomies of scale may occur if as industry output rises the unit price of factors and materials rises as well due to increasing competition for inputs with other industries.

It should be made clear that these long-run results only hold if producer are rational actors, that is able to optimize their production so as to have an optimal scale of plant.

Imperfect competition and game theory

In 1929 Harold Hotelling published "Stability in Competition" addressing the problem of instability in the classic Cournout model: Bertrand criticized it for lacking equilibrium for prices as independent variables and Edgeworth constructed a dual monopoly model with correlated demand with also lacked stability. Hotteling proposed that demand typically varied continuously for relative prices, not discontinuously as suggested by the later authors.[19]

Following Sraffa he argued for "the existence with reference to each seller of groups who will deal with him instead of his competitors in spite of difference in price", he also noticed that traditional models that presumed the uniqueness of price in the market only made sense if the commodity was standardized and the market was a point: akin to a temperature model in physics, discontinuity in heat transfer (price changes) inside a body (market) would lead to instability. To show the point he built a model of market located over a line with two sellers in each extreme of the line, in this case maximizing profit for both sellers leads to a stable equilibrium. From this model also follows that if a seller is to choose the location of his store so as to maximize his profit, he will place his store the closest to his competitor: "the sharper competition with his rival is offset by the greater number of buyers he has an advantage". He also argues that clustering of stores is wasteful from the point of view of transportation costs and that public interest would dictate more spatial dispersion.

A new impetus was given to the field when around 1933 Joan Robinson and Edward H. Chamberlin, published respectively, The Economics of Imperfect Competition (1933) and The Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933), introducing models of imperfect competition.[20][21] Although the monopoly case was already exposed in Marshall's Principles of Economics and Cournot had already constructed models of duopoly and monopoly in 1838, a whole new set of models grew out of this new literature. In particular the monopolistic competition model results in a non efficient equilibrium. Chamberlin defined monopolistic competition as, "...challenge to traditional viewpoint of economics that competition and monopoly are alternatives and that individual prices are to be explained in terms of one or the other." He continues, "By contrast it is held that most economic situations are composite of both competition and monopoly, and that, wherever this is the case, a false view is given by neglecting either one of the two forces and regarding the situation as made up entirely of the other."[22]

Later, some market models were built using game theory, particularly regarding oligopolies. A good example of how microeconomics started to incorporate game theory, is the Stackelberg competition model published in 1934,[23] which can be characterized as a dynamic game with a leader and a follower, and then be solved to find a Nash Equilibrium.

William Baumol provided in his 1977 paper the current formal definition of a natural monopoly where “an industry in which multiform production is more costly than production by a monopoly” (p. 810):[24] mathematically this equivalent to subadditivity of the cost function. He then sets out to prove 12 propositions related to strict economies of scale, ray average costs, ray concavity and transray convexity: in particular strictly declining ray average cost implies strict declining ray subadditivity, global economies of scale are sufficient but not necessary for strict ray subadditivity.

In 1982 paper[25] Baumol defined a contestable market as a market where "entry is absolutely free and exit absolutely costless", freedom of entry in Stigler sense: the incumbent has no cost discrimination against entrants. He states that a contestable market will never have an economic profit greater than zero when in equilibrium and the equilibrium will also be efficient. According to Baumol this equilibrium emerges endogenously due to the nature of contestable markets, that is the only industry structure that survives in the long run is the one which minimizes total costs. This is in contrast to the older theory of industry structure since not only industry structure is not exogenously given, but equilibrium is reached without add hoc hypothesis on the behavior of firms, say using reaction functions in a duopoly. He concludes the paper commenting that regulators that seek to impede entry and/or exit of firms would do better to not interfere if the market in question resembles a contestable market.

Externalities and market failure

In 1937, “The Nature of the Firm” was published by Coase introducing the notion of transaction costs (the term itself was coined in the fifties), which explained why firms have an advantage over a group of independent contractors working with each other.[26] The idea was that there were transaction costs in the use of the market: search and information costs, bargaining costs, etc., which give an advantage to a firm that can internalize the production process required to deliver a certain good to the market. A related result was published by Coase in his “The Problem of Social Cost” (1960), which analyses solutions of the problem of externalities through bargaining,[27] in which he first describes a cattle herd invading a farmer's crop and then discusses four legal cases: Sturges v Bridgman, Cooke v Forbes, Bryant v Lejever, and Bass v Gregory. He then states:

"In earlier sections, when dealing with the problem of rearrangement of legal rights through the market, it was argued that such a rearrangement would be made through the market whenever this would lead to an increase in the value of production. But this assumed costless market transactions. Once the costs of carrying out market transactions are taken into account it is clear that such rearrangement of rights will only be undertaken when the increase in the value of production consequent upon the rearrangement is greater than the costs which would be involved in bringing it about. When it is less, the granting of an injunction (or the knowledge that it would be granted) or the liability to pay damages may result in an activity being discontinued (or may prevent its being started) which would be undertaken if market transactions were costless. In these conditions the initial delimitation of legal rights does have an effect on the efficiency with which the economic system operates. One arrangement of rights may bring about a greater value of production than any other. But unless this is the arrangement of rights established by the legal system, the costs of reaching the same result by altering and combining rights through the market may be so great that this optimal arrangement of rights, and the greater value of production which it would bring, may never be achieved."

This then becomes relevant in context of regulations. He argues against the Pigovian tradition:[28]

"...The problem which we face in dealing with actions which have harmful effects is not simply one of restraining those responsible for them. What has to be decided is whether the gain from preventing the harm is greater than the loss which would be suffered elsewhere as a result of stopping the action which produces the harm. In a world in which there are costs of rearranging the rights established by the legal system, the courts, in cases relating to nuisance, are, in effect, making a decision on the economic problem and determining how resources are to be employed. It was argued that the courts are conscious of this and that they often make, although not always in a very explicit fashion, a comparison between what would be gained and what lost by preventing actions which have harmful effects. But the delimitation of rights is also the result of statutory enactments. Here we also find evidence of an appreciation of the reciprocal nature of the problem. While statutory enactments add to the list of nuisances, action is also taken to legalize what would otherwise be nuisances under the common law. The kind of situation which economists are prone to consider as requiring Government action is, in fact, often the result of Government action. Such action is not necessarily unwise. But there is a real danger that extensive Government intervention in the economic system may lead to the protection of those responsible for harmful being carried too far."

This period also marks the beginning of mathematical modeling of public goods with Samuelson's “The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure” (1954), in it he gives a set of equations for efficient provision of public goods (he called them collective consumption goods), now know as the Samuelson condition.[29] He then gives a description of what is know called the free rider problem:

"However no decentralized pricing system can serve to determine optimally these levels of collective consumption. Other kinds of "voting" or "signaling" would have to be tried. But, and this is the point sensed by Wicksell but perhaps not fully appreciated by Lindahl, now it is in the selfish interest of each person to give false signals, to pretend to have less interest in a given collective consumption activity than he has, etc."

Around the 1970s the study of market failures again came into focus with the study of information asymmetry. In particular three authors emerged from this period: Akerlof, Spence, and Stiglitz. Akerlof considered the problem of bad quality cars driving good quality cars out of the market in his classic “The Market for Lemons” (1970) because of the presence of asymmetrical information between buyers and sellers.[30] Spence explained that signaling was fundamental in the labour market, because since employers can't know beforehand which candidate is the most productive, a college degree becomes a signaling device that a firm uses to select new personnel.[31] A synthesizing paper of this era is “Externalities in Economies with Imperfect Information and Incomplete Markets” by Stiglitz and Greenwald:[32] the basic model consists of households that maximize a utility function, firms that maximize profit—and a government that produces nothing, collects taxes, and distributes the proceeds. An initial equilibrium with no taxes is assumed to exist, a vector x of household consumption and vector z of other variables that affect household utilities (externalities) are defined, a vector π of profits is defined along with a vector E of households expenditures. Since the envelope theorem holds, if the initial non taxed equilibrium is Pareto optimal then it follows that the dot products Π (between π and the time derivative of z) and B (between E and the time derivative of z) must equal each other. They state:

"Except in the special case (which is unlikely to hold generically) where Π and B exactly cancel each other out, the existence of these externalities will make the initial equilibrium inefficient and guarantee the existence of welfare-improving tax measures."

One application of this result is to the already mentioned Market for Lemons, which deals with adverse selection: households buy from a pool of goods with heterogeneous quality considering only average quality, since in general the equilibrium is not efficient, any tax that raises average quality is beneficial (in the sense of optimal taxation). Other applications were considered by the authors, such as tax distortions, signaling, screening, moral hazard, incomplete markets, queue rationing, unemployment and rationing equilibrium.

Behavioral economics

Kahneman and Tversky published a paper in 1979 criticizing the very idea of the rational economic agent.[33] The main point is that there is an asymmetry in the psychology of the economic agent that gives a much higher value to losses than to gains. This article is usually regarded as the beginning of behavioral economics and has consequences particularly regarding the world of finance. The authors summed the idea in the abstract as follows:

"...In particular, people underweight outcomes that are merely probable in comparison with outcomes that are obtained with certainty. This tendency, called certainty effect, contributes to risk aversion in choices involving sure gains and to risk seeking in choices involving sure losses. In addition, people generally discard components that are shared by all prospects under consideration. This tendency, called the isolation effect, leads to inconsistent preferences when the same choice is presented in different forms."

Great Recession and executive compensation

More recently, the Great Recession and the ongoing controversy on executive compensation brought the principal–agent problem again to the center of debate, in particular regarding corporate governance and problems with incentive structures.[34]

References

- ^ Marchant, Mary A.; Snell, William M. "Macroeconomic and International Policy Terms" (PDF). University of Kentucky. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "Economics Glossary". Monroe County Women's Disability Network. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Social Studies Standards Glossary". New Mexico Public Education Department. Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Glossary". ECON100. Retrieved 2008-02-22.

- ^ "Macroeconomics vs. Microeconomics". Retrieved 2014-10-24.

- ^ http://www.ftc.gov/bc/edu/pubs/consumer/general/zgen01.shtm

- ^ Deardorff's Glossary of International Economics (2006). "Welfare economics."

- ^ • Beth Allen, 1990. "Information as an Economic Commodity," American Economic Review, 80(2), pp. 268–273.

• Kenneth J. Arrow, 1999. "Information and the Organization of Industry," ch. 1, in Graciela Chichilnisky Markets, Information, and Uncertainty. Cambridge University Press, pp. 20–21.

• _____, 1996. "The Economics of Information: An Exposition," Empirica, 23(2), pp. 119–128.

• _____, 1984. Collected Papers of Kenneth J. Arrow, v. 4, The Economics of Information. Description and chapter-preview links.

• Jean-Jacques Laffont, 1989. The Economics of Uncertainty and Information, MIT Press. Description and chapter-preview links. - ^ A. Cournot, Researches into the mathematical principles of the theory of wealth, 1838 http://archive.org/details/researchesintom00fishgoog

- ^ S. Jevon, The Theory of Political Economy,1871 http://www.econlib.org/library/YPDBooks/Jevons/jvnPE.html

- ^ C.Menger,Principles of Economics, 1871 https://mises.org/etexts/menger/principles.asp

- ^ Leon Walras, Elements of Pure Economics, 1874 http://books.google.it/books/about/Elements_of_Pure_Economics.html?id=hwjRD3z0Qy4C&redir_esc=y

- ^ A. Marshall, Principles of Economics, 1890 http://www.econlib.org/library/Marshall/marP.html

- ^ A.Marshall, Principles of Economics, 1890, APPENDIX I:RICARDO'S THEORY OF VALUE http://www.econlib.org/library/Marshall/marP64.html

- ^ A.Marshall, Principles of Economics, 1890, BOOK VI, CHAPTER II: PRELIMINARY SURVEY OF DISTRIBUTION, CONTINUED. http://www.econlib.org/library/Marshall/marP44.html#Bk.VI,Ch.II

- ^ Thünen, J. H. von (1826). Der isolierte Staat in Beziehung auf Landwirthschaft und Nationalökonomie. 3 volumes. Jena, Germany: Fischer.

- ^ Cobb, C. W.; Douglas, P. H. (1928). "A Theory of Production". American Economic Review. 18 (Supplement): 139–165. JSTOR 1811556.

- ^ Viner, Jacob (1931). "Costs Curves and Supply Curves". Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie. 3 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1007/BF01316299. Reprinted in Emmett, R. B., ed. (2002). The Chicago Tradition in Economics, 1892–1945. Vol. 6. Routledge. pp. 192–215.

- ^ Hotteling, H. (1929). "Stability in Competition". The Economic Journal. 39 (153): 41–57. JSTOR 2224214.

- ^ Robinson, J. (1933). The Economics of Imperfect Competition. London: Macmillan. OCLC 270400.

- ^ Chamberlin, E. H. (1933). The Theory of Monopolistic Competition. Harvard Economic Studies. Vol. 38. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. OCLC 1099674.

- ^ Chamberlin, E. H. (1937). "Monopolistic or Imperfect Competition?". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 51 (4): 557–580. doi:10.2307/1881679.

- ^ Stackelberg, H. F. von (1934). Marktform und Gleichgewicht. Berlin: J. Springer. OCLC 5046822.

- ^ Baumol, William J. (1977). "On the Proper Cost Tests for Natural Monopoly in a Multiproduct Industry". American Economic Review. 67 (5): 809–822. JSTOR 1828065.

- ^ Baumol W., Contestable Markets: An Uprising in the Theory of Industry Structure, American Economic Review vol 72 pp. 1-15 1982 http://econ.ucdenver.edu/beckman/research/readings/baumol-contestable.pdf

- ^ Coase, R. H. (1937). "The Nature of the Firm". Economica. 4 (16): 386–405. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x.

- ^ Coase, R. H. (1960). "The Problem of Social Cost". Journal of Law and Economics. 3: 1–44. doi:10.1086/466560. JSTOR 724810.

- ^ Pigou, Arthur Cecil (1920). The Economics of Welfare.

- ^ Samuelson, P. (1954). "The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure". Review of Economics and Statistics. 36 (4): 387–389. JSTOR 1925895.

- ^ Akerlof, George A. (1970). "The Market for 'Lemons': Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 84 (3): 488–500. doi:10.2307/1879431.

- ^ Spence, A. M. (1973). "Job Market Signaling". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. JSTOR 1882010.

- ^ Greenwald, Bruce; Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1986). "Externalities in Economics with Incomplete Market Information". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 101 (2): 229–264. doi:10.2307/1891114.

- ^ Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. (1979). "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk". Econometrica. 47 (2): 263–292. JSTOR 1914185.

- ^ "Economist Joseph Stiglitz: Put Corporate Criminals in Jail". Daily Finance. October 22, 2010.

Further reading

- Bade, Robin; Michael Parkin (2001). Foundations of Microeconomics. Addison Wesley Paperback 1st Edition.

- Bouman, John: Principles of Microeconomics – free fully comprehensive Principles of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics texts. Columbia, Maryland, 2011

- Colander, David. Microeconomics. McGraw-Hill Paperback, 7th Edition: 2008.

- Dunne, Timothy, J. Bradford Jensen, and Mark J. Roberts (2009). Producer Dynamics: New Evidence from Micro Data. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-17256-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eaton, B. Curtis; Eaton, Diane F.; and Douglas W. Allen. Microeconomics. Prentice Hall, 5th Edition: 2002.

- Frank, Robert H.; Microeconomics and Behavior. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 6th Edition: 2006.

- Friedman, Milton. Price Theory. Aldine Transaction: 1976

- Hagendorf, Klaus: Labour Values and the Theory of the Firm. Part I: The Competitive Firm. Paris: EURODOS; 2009.

- Harnerger, Arnold C. (2008). "Microeconomics". In David R. Henderson (ed.) (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Hicks, John R. Value and Capital. Clarendon Press. [1939] 1946, 2nd ed.

- Hirshleifer, Jack., Glazer, Amihai, and Hirshleifer, David, Price theory and applications: Decisions, markets, and information. Cambridge University Press, 7th Edition: 2005.

- Jehle, Geoffrey A.; and Philip J. Reny. Advanced Microeconomic Theory. Addison Wesley Paperback, 2nd Edition: 2000.

- Katz, Michael L.; and Harvey S. Rosen. Microeconomics. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 3rd Edition: 1997.

- Kreps, David M. A Course in Microeconomic Theory. Princeton University Press: 1990

- Landsburg, Steven. Price Theory and Applications. South-Western College Pub, 5th Edition: 2001.

- Mankiw, N. Gregory. Principles of Microeconomics. South-Western Pub, 2nd Edition: 2000.

- Mas-Colell, Andreu; Whinston, Michael D.; and Jerry R. Green. Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press, US: 1995.

- McGuigan, James R.; Moyer, R. Charles; and Frederick H. Harris. Managerial Economics: Applications, Strategy and Tactics. South-Western Educational Publishing, 9th Edition: 2001.

- Nicholson, Walter. Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions. South-Western College Pub, 8th Edition: 2001.

- Perloff, Jeffrey M. Microeconomics. Pearson – Addison Wesley, 4th Edition: 2007.

- Perloff, Jeffrey M. Microeconomics: Theory and Applications with Calculus. Pearson – Addison Wesley, 1st Edition: 2007

- Pindyck, Robert S.; and Daniel L. Rubinfeld. Microeconomics. Prentice Hall, 7th Edition: 2008.

- Ruffin, Roy J.; and Paul R. Gregory. Principles of Microeconomics. Addison Wesley, 7th Edition: 2000.

- Varian, Hal R. (1987). "microeconomics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 461–63.

- Varian, Hal R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach. W. W. Norton & Company, 8th Edition: 2009.

- Varian, Hal R. Microeconomic Analysis. W. W. Norton & Company, 3rd Edition: 1992.

External links

- Open Source Introduction to Microeconomics (see wiki article) by R. Preston McAfee – California Institute of Technology

- Amosweb.com homepage – online economics dictionary

- X-Lab: A Collaborative Micro-Economics and Social Sciences Research Laboratory

- Micro Economics – the role of microeconomics in supporting the social fabric of macro economies

- Simulations in Microeconomics

- An introductory microeconomics podcast

- http://media.lanecc.edu/users/martinezp/201/MicroHistory.html – a brief history of microeconomics