Montaña Palentina Natural Park

| Montaña Palentina Natural Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

The landscape of the park show the effects of glaciation in the last glacial period. | |

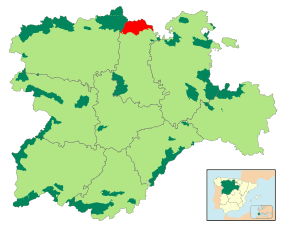

Location of the natural park within Castile and León | |

| Coordinates | 42°56′N 4°35′W / 42.94°N 4.58°W |

| Area | 78,360 ha (193,600 acres) |

| Visitors | 21179 (in 2007) |

| Governing body | Junta de Castilla y Léon |

Montaña Palentina (Spanish: Parque natural de la Montaña Palentina) is a natural park in the north of the province of Palencia in Castile and León, Spain.

The park was declared in 2000 with the name "Fuentes Carrionas and Fuente Cobre-Montaña Palentina". The original name of the park refers to:

- the Fuentes Carrionas sub-range of the Cantabrian Mountains (source of the river Carrión)

- Fuente Cobre (the traditional source of the river Pisuerga).

It is one of a number of protected areas in the Cantabrian Mountains. From an ecological point of view, most of the park is within the Atlantic biogeographical region, but it is on the edge of that region and 4% of the area is classed as Mediterranean.

Fauna[edit]

In 1998 the natural park was proposed as a Site of Community Importance. In 2000 It was designated a Special Protection Area (SPA) for bird-life (reference number ES4140011) under the European Union's Birds Directive. In 2015 it was designated a Special Area of Conservation (SAC) under the Habitats Directive.[1][2]

Birds[edit]

The Cantabrian Capercaillie became extinct in the natural park at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Since 2010 the European Union's LIFE programme has supported a recovery plan for this subspecies, "Urgent measures scheme for the conservation of the capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus cantabricus) and its habitat in the Cantabrian mountains". This project was scheduled to run until 2014 across SPAs and Biosphere reserves in the region, and the natural park has been identified as a suitable site for the bird's reintroduction.[3][4]

Invertebrates[edit]

Invertebrates include the Kerry Slug.

Mammals[edit]

Cantabrian brown bear[edit]

The park is important as a habitat of the endangered Cantabrian brown bear. There is an interpretation centre for the bear at Verdeña, Cervera de Pisuerga.[5]

In the twentieth century, the Cantabrian brown bears were divided into two sub-populations by habitat fragmentation. The natural park lies within the range of the eastern subpopulation, which is the smaller of the two and at risk from endogamy. In 2009 a genetic study indicated that the bears had reversed the division of their range in Spain, and there is inter-breeding between the two sub-populations.[6] Since 2009 the LIFE Programme has supported conservation work in the Cantabrian Mountains to enhance wildlife corridors with the aim of encouraging a natural flow of bears between sub-populations.[7]

European bison[edit]

European bison live in an enclosure at San Cebrián de Mudá.[8]

Conservation issues[edit]

Hunting[edit]

A national hunting reserve, the Reserva Nacional de Caza de Fuentes Carrionas, was in existence prior to the designation of the natural park, and it now forms a regional hunting reserve within the park boundaries. With an area of 49, 471 ha the hunting reserve covers the greater part of the natural park. While the hunting has been described as well-managed,[9] there is some controversy as to whether a management regime appropriate for game species such as wild boar or deer is compatible with the interests of the protected species.[10]

San Glorio Ski Resort[edit]

In 2004, a ski resort was proposed for the mountain pass of San Glorio which would directly impact the natural park. In 2006, the regional government relaxed the protection it had given the park in order to permit the development of a ski resort. The promoters of the project argued that it would help the local human population. There are about 2000 people living in the park. The area, like many Spanish rural districts, suffered from demographic decline in the twentieth century.

Environmentalists have disputed the economics of the project as, according to official predictions, the duration of seasonal snow cover in the Cantabrian mountains was likely to be adversely affected by global warming. Environmentalists have also argued that a ski resort would be incompatible with the aim of promoting the recovery of the brown bear, given that bears would be likely to avoid such a facility and that their habitat would thus be fragmented.[11]

In March 2008, the High Court of Castilla y León ruled that the regional government's sudden change in its own planning regulations, without a proper assessment, not only went against its own regional law, but both the national law on nature conservation and the European Natura 2000 regulations. The court also noted that climate change threatened the viability of the projected ski resort.[12] However, despite this setback, the regional government continued to support the development. As at July 2010 the regional government was planning to submit a revised proposal to the European Union in the hope that it would not conflict with the Habitats Directive.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Fuentes Carrionas y Fuente Cobre-Montaña Palentina (Natura 2000 data set)". European Environment Agency. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ^ (in Spanish) Natura 2000 listing. Spanish Ministry of the Environment

- ^ Cantabrian Capercaillie Protection Scheme, Fundacion Iberdrola

- ^ (in Spanish) Urogallo Cantábrico (LIFE+ Cantabrian Capercaillie website)

- ^ (in Spanish) Fundación Oso Pardo, Official website of Brown Bear NGO

- ^ (in Spanish) El oso cantábrico salta la autovía para reproducirse, Pedro Cáceres, El Mundo

- ^ LIFE+ Project Brown Bear Corridors Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine, Fundación Oso Pardo

- ^ "BISONBONASUS. Reserve and Interpretation Centre of the European Bison". Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Cantabrian Mountains, Large Herbivore Network

- ^ El oso de Fuentes Carrionas (Palencia) fue herido en zona de caza prohibida

- ^ This view was supported by The Guardian newspaper in 2010 when it included San Glorio in a biodiversity campaign.[1]

- ^ (in Spanish) Rafael Méndez (2008-04-02), La justicia veta una estación de esquí al ser inviable con el cambio de clima, El País. See also English version.