Natural selection

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype.[1] It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in heritable traits of a population over time.[2] Charles Darwin popularised the term "natural selection"; he compared it with artificial selection (selective breeding).

Variation exists within all populations of organisms. This occurs partly because random mutations arise in the genome of an individual organism, and offspring can inherit such mutations. Throughout the lives of the individuals, their genomes interact with their environments to cause variations in traits. (The environment of a genome includes the molecular biology in the cell, other cells, other individuals, populations, species, as well as the abiotic environment.) Individuals with certain variants of the trait may survive and reproduce more than individuals with other, less successful, variants. Therefore, the population evolves. Factors that affect reproductive success are also important, an issue that Darwin developed in his ideas on sexual selection (now often included in natural selection[3][4]) and on fecundity selection, for example.

Natural selection acts on the phenotype, or the observable characteristics of an organism, but the genetic (heritable) basis of any phenotype that gives a reproductive advantage may become more common in a population (see allele frequency). Over time, this process can result in populations that specialise for particular ecological niches (microevolution) and may eventually result in the emergence of new species (macroevolution). In other words, natural selection is an important process (though not the only process) by which evolution takes place within a population of organisms. Natural selection can be contrasted with artificial selection, in which humans intentionally choose specific traits (although they may not always get what they want). In natural selection there is no intentional choice. In other words, artificial selection is teleological and natural selection is not teleological, though biologists often use teleological language to describe it.[5]

Natural selection is one of the cornerstones of modern biology. The concept, published by Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace in a joint presentation of papers in 1858, was elaborated in Darwin's influential 1859 book On the Origin of Species,[6] which described natural selection as analogous to artificial selection, a process by which animals and plants with traits considered desirable by human breeders are systematically favoured for reproduction. The concept of natural selection originally developed in the absence of a valid theory of heredity; at the time of Darwin's writing, science had yet to develop modern theories of genetics. The union of traditional Darwinian evolution with subsequent discoveries in classical and molecular genetics is termed the modern evolutionary synthesis. Natural selection remains the primary explanation for adaptive evolution.

General principles

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Natural variation occurs among the individuals of any population of organisms. Many of these differences do not affect survival or reproduction, but some differences may improve the chances of survival and reproduction of a particular individual. A rabbit that runs faster than others may be more likely to escape from predators, and algae that are more efficient at extracting energy from sunlight will grow faster. Something that increases an organism's chances of survival will often also include its reproductive rate; however, sometimes there is a trade-off between survival and current reproduction. Ultimately, what matters is total lifetime reproduction of the organism.

The peppered moth exists in both light and dark colours in the United Kingdom, but during the industrial revolution, many of the trees on which the moths rested became blackened by soot, giving the dark-coloured moths an advantage in hiding from predators. This gave dark-coloured moths a better chance of surviving to produce dark-coloured offspring, and in just fifty years from the first dark moth being caught, nearly all of the moths in industrial Manchester were dark. The balance was reversed by the effect of the Clean Air Act 1956, and the dark moths became rare again, demonstrating the influence of natural selection on peppered moth evolution.[7]

If the traits that give these individuals a reproductive advantage are also heritable, that is, passed from parent to offspring, then there will be a slightly higher proportion of fast rabbits or efficient algae in the next generation. This is known as differential reproduction. Even if the reproductive advantage is very slight, over many generations any heritable advantage will become dominant in the population. In this way the natural environment of an organism "selects" for traits that confer a reproductive advantage, causing gradual changes or evolution of life. This effect was first described and named by Charles Darwin.

The concept of natural selection predates the understanding of genetics, the mechanism of heredity for all known life forms. In modern terms, selection acts on an organism's phenotype, or observable characteristics, but it is the organism's genetic make-up or genotype that is inherited. The phenotype is the result of the genotype and the environment in which the organism lives (see Genotype-phenotype distinction).

This is the link between natural selection and genetics, as described in the modern evolutionary synthesis. Although a complete theory of evolution also requires an account of how genetic variation arises in the first place (such as by mutation and sexual reproduction) and includes other evolutionary mechanisms (such as genetic drift and gene flow), natural selection appears to be the most important mechanism for creating complex adaptations in nature.

Nomenclature and usage

The term natural selection has slightly different definitions in different contexts. It is most often defined to operate on heritable traits, because these are the traits that directly participate in evolution. However, natural selection is "blind" in the sense that changes in phenotype (physical and behavioural characteristics) can give a reproductive advantage regardless of whether or not the trait is heritable (non heritable traits can be the result of environmental factors or the life experience of the organism).

Following Darwin's primary usage[6] the term is often used to refer to both the evolutionary consequence of blind selection and to its mechanisms.[8][9] It is sometimes helpful to explicitly distinguish between selection's mechanisms and its effects; when this distinction is important, scientists define "natural selection" specifically as "those mechanisms that contribute to the selection of individuals that reproduce," without regard to whether the basis of the selection is heritable. This is sometimes referred to as "phenotypic natural selection."[10]

Traits that cause greater reproductive success of an organism are said to be selected for, whereas those that reduce success are selected against. Selection for a trait may also result in the selection of other correlated traits that do not themselves directly influence reproductive advantage. This may occur as a result of pleiotropy or gene linkage.[11]

Fitness

The concept of fitness is central to natural selection. In broad terms, individuals that are more "fit" have better potential for survival, as in the well-known phrase "survival of the fittest." However, as with natural selection above, the precise meaning of the term is much more subtle. Modern evolutionary theory defines fitness not by how long an organism lives, but by how successful it is at reproducing. If an organism lives half as long as others of its species, but has twice as many offspring surviving to adulthood, its genes will become more common in the adult population of the next generation.

Though natural selection acts on individuals, the effects of chance mean that fitness can only really be defined "on average" for the individuals within a population. The fitness of a particular genotype corresponds to the average effect on all individuals with that genotype. Very low-fitness genotypes cause their bearers to have few or no offspring on average; examples include many human genetic disorders like cystic fibrosis.

Since fitness is an averaged quantity, it is also possible that a favourable mutation arises in an individual that does not survive to adulthood for unrelated reasons. Fitness also depends crucially upon the environment. Conditions like sickle-cell anaemia may have low fitness in the general human population, but because the sickle cell trait confers immunity from malaria, it has high fitness value in populations that have high malaria infection rates.

Types of selection

Natural selection can act on any heritable phenotypic trait, and selective pressure can be produced by any aspect of the environment, including sexual selection and competition with members of the same or other species. However, this does not imply that natural selection is always directional and results in adaptive evolution; natural selection often results in the maintenance of the status quo by eliminating less fit variants.

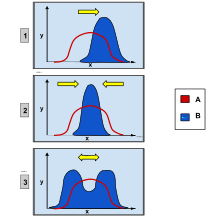

Selection can be classified according to its effect on a trait. Stabilizing selection acts to hold a trait at a stable optimum, and in the simplest case all deviations from this optimum are selectively disadvantageous. Directional selection favours extreme values of a trait. Disruptive selection also acts during transition periods when the current mode is sub-optimal, but alters the trait in more than one direction. In particular, if the trait is quantitative and univariate then both higher and lower trait levels are favoured. Disruptive selection can be a precursor to speciation.

Selection can also be classified according to its effect on genetic diversity. Purifying selection acts to remove genetic variation from the population (and is opposed by de novo mutation, which introduces new variation). Balancing selection acts to maintain genetic variation in a population (even in the absence of de novo mutation). Mechanisms include negative frequency-dependent selection (of which heterozygote advantage is a special case), and spatial and/or temporal fluctuations in the strength and direction of selection.

Selection can also be classified according to the stage of an organism’s life cycle at which it acts. The use of terminology differs here. Some recognise just two types of selection: viability selection (or survival selection) which acts to improve the probability of survival of the organism, and fecundity selection (or fertility selection, or reproductive selection) which acts to improve the rate of reproduction, given successful survival. Others split the life cycle into further components of selection (see figure). Thus viability and survival selection may be defined separately and respectively as acting to improve the probability of survival before and after reproductive age is reached, while fecundity selection may be split into additional sub-components including sexual selection, gametic selection (acting on gamete survival) and compatibility selection (acting on zygote formation).

Selection can also be classified according to the level or unit of selection. Individual selection acts at the level of the individual, in the sense that adaptions are ‘for’ the benefit of the individual, and result from selection among individuals. Gene selection acts directly at the level of the gene. In many situations, this is simply a different way of describing individual selection. However, in some cases (e.g., kin selection and intragenomic conflict), gene-level selection provides a more apt explanation of the underlying process. Group selection acts at the level of groups of organisms. The mechanism assumes that groups replicate and mutate in an analogous way to genes and individuals. There is an ongoing debate over the degree to which group selection occurs in nature.

Finally, selection can be classified according to the resource being competed for. Sexual selection results from competition for mates. Sexual selection can be intrasexual, as in cases of competition among individuals of the same sex in a population, or intersexual, as in cases where one sex controls reproductive access by choosing among a population of available mates. Typically, sexual selection proceeds via fecundity selection, sometimes at the expense of viability. Ecological selection is natural selection via any other means than sexual selection. Alternatively, natural selection is sometimes defined as synonymous with ecological selection, and sexual selection is then classified as a separate mechanism to natural selection. This accords with Darwin’s usage of these terms, but ignores the fact that mate competition and mate choice are natural processes.[13]

Note that types of selection often act in concert. Thus Stabilizing selection typically proceeds via negative selection on rare alleles, leading to purifying selection, while directional selection typically proceeds via positive selection on an initially rare favoured allele.

Ecological selection covers any mechanism of selection as a result of the environment, including relatives (e.g., kin selection, competition, and infanticide).

Sexual selection

Sexual selection refers specifically to competition for mates,[14] which can be intrasexual, between individuals of the same sex, that is male–male competition, or intersexual, where one gender choose mates. However, some species exhibit sex-role reversed behaviour in which it is males that are most selective in mate choice; such as in some fishes of the family Syngnathidae, though likely examples have also been found in sexual selection in amphibians, sexual selection in birds, sexual selection in mammals (including sexual selection in humans) and sexual selection in scaled reptiles.[15]

Phenotypic traits can be displayed in one sex and desired in the other sex, causing a positive feedback loop called a Fisherian runaway, for example, the extravagant plumage of some male birds. An alternate theory proposed by the same Ronald Fisher in 1930 is the sexy son hypothesis, that mothers will want promiscuous sons to give them large numbers of grandchildren and so will choose promiscuous fathers for their children. Aggression between members of the same sex is sometimes associated with very distinctive features, such as the antlers of stags, which are used in combat with other stags. More generally, intrasexual selection is often associated with sexual dimorphism, including differences in body size between males and females of a species.[16]

Examples of natural selection

A well-known example of natural selection in action is the development of antibiotic resistance in microorganisms. Since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, antibiotics have been used to fight bacterial diseases. Natural populations of bacteria contain, among their vast numbers of individual members, considerable variation in their genetic material, primarily as the result of mutations. When exposed to antibiotics, most bacteria die quickly, but some may have mutations that make them slightly less susceptible. If the exposure to antibiotics is short, these individuals will survive the treatment. This selective elimination of maladapted individuals from a population is natural selection.

These surviving bacteria will then reproduce again, producing the next generation. Due to the elimination of the maladapted individuals in the past generation, this population contains more bacteria that have some resistance against the antibiotic. At the same time, new mutations occur, contributing new genetic variation to the existing genetic variation. Spontaneous mutations are very rare, and advantageous mutations are even rarer. However, populations of bacteria are large enough that a few individuals will have beneficial mutations. If a new mutation reduces their susceptibility to an antibiotic, these individuals are more likely to survive when next confronted with that antibiotic.

Given enough time and repeated exposure to the antibiotic, a population of antibiotic-resistant bacteria will emerge. This new changed population of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is optimally adapted to the context it evolved in. At the same time, it is not necessarily optimally adapted any more to the old antibiotic free environment. The end result of natural selection is two populations that are both optimally adapted to their specific environment, while both perform substandard in the other environment.

The widespread use and misuse of antibiotics has resulted in increased microbial resistance to antibiotics in clinical use, to the point that the methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has been described as a "superbug" because of the threat it poses to health and its relative invulnerability to existing drugs.[citation needed] Response strategies typically include the use of different, stronger antibiotics; however, new strains of MRSA have recently emerged that are resistant even to these drugs.[17]

This is an example of what is known as an evolutionary arms race, in which bacteria continue to develop strains that are less susceptible to antibiotics, while medical researchers continue to develop new antibiotics that can kill them. A similar situation occurs with pesticide resistance in plants and insects. Arms races are not necessarily induced by man; a well-documented example involves the spread of a gene in the butterfly Hypolimnas bolina suppressing male-killing activity by Wolbachia bacteria parasites on the island of Samoa, where the spread of the gene is known to have occurred over a period of just five years [18]

Evolution by means of natural selection

A prerequisite for natural selection to result in adaptive evolution, novel traits and speciation, is the presence of heritable genetic variation that results in fitness differences. Genetic variation is the result of mutations, genetic recombinations and alterations in the karyotype (the number, shape, size and internal arrangement of the chromosomes). Any of these changes might have an effect that is highly advantageous or highly disadvantageous, but large effects are very rare. In the past, most changes in the genetic material were considered neutral or close to neutral because they occurred in noncoding DNA or resulted in a synonymous substitution. However, recent research suggests that many mutations in non-coding DNA do have slight deleterious effects.[19][20] Although both mutation rates and average fitness effects of mutations are dependent on the organism, estimates from data in humans have found that a majority of mutations are slightly deleterious.[21]

By the definition of fitness, individuals with greater fitness are more likely to contribute offspring to the next generation, while individuals with lesser fitness are more likely to die early or fail to reproduce. As a result, alleles that on average result in greater fitness become more abundant in the next generation, while alleles that in general reduce fitness become rarer. If the selection forces remain the same for many generations, beneficial alleles become more and more abundant, until they dominate the population, while alleles with a lesser fitness disappear. In every generation, new mutations and re-combinations arise spontaneously, producing a new spectrum of phenotypes. Therefore, each new generation will be enriched by the increasing abundance of alleles that contribute to those traits that were favoured by selection, enhancing these traits over successive generations.

Some mutations occur in so-called regulatory genes. Changes in these can have large effects on the phenotype of the individual because they regulate the function of many other genes. Most, but not all, mutations in regulatory genes result in non-viable zygotes. Examples of nonlethal regulatory mutations occur in HOX genes in humans, which can result in a cervical rib[22] or polydactyly, an increase in the number of fingers or toes.[23] When such mutations result in a higher fitness, natural selection will favour these phenotypes and the novel trait will spread in the population.

Established traits are not immutable; traits that have high fitness in one environmental context may be much less fit if environmental conditions change. In the absence of natural selection to preserve such a trait, it will become more variable and deteriorate over time, possibly resulting in a vestigial manifestation of the trait, also called evolutionary baggage. In many circumstances, the apparently vestigial structure may retain a limited functionality, or may be co-opted for other advantageous traits in a phenomenon known as preadaptation. A famous example of a vestigial structure, the eye of the blind mole-rat, is believed to retain function in photoperiod perception.[24]

Speciation

Speciation requires some amount of reproductive isolation—that is, a reduction in gene flow. Over time, isolated subgroups might diverge radically to become different species, either because of differences in selection pressures on the different subgroups, or because different mutations arise spontaneously in the different populations, or because of genetic drift which is responsible for phenomena such as bottleneck effect and founder effect. A lesser-known mechanism of speciation occurs via hybridisation, well-documented in plants and occasionally observed in species-rich groups of animals such as cichlid fishes.[25] Such mechanisms of rapid speciation can reflect a mechanism of evolutionary change known as punctuated equilibrium, which suggests that evolutionary change and in particular speciation typically happens quickly after long periods of stasis.

Genetic changes within groups result in increasing incompatibility between the genomes of the two subgroups, thus reducing gene flow between the groups. Gene flow will effectively cease when the distinctive mutations characterising each subgroup become fixed. As few as two mutations can result in speciation: if each mutation has a neutral or positive effect on fitness when they occur separately, but a negative effect when they occur together, then fixation of these genes in the respective subgroups will lead to two reproductively isolated populations. According to the biological species concept, these will be two different species.

Historical development

Pre-Darwinian theories

Several ancient philosophers expressed the idea that nature produces a huge variety of creatures, randomly, and that only those creatures that manage to provide for themselves and reproduce successfully survive; well-known examples include Empedocles[26] and his intellectual successor, the Roman poet Lucretius.[27] Empedocles' idea that organisms arose entirely by the incidental workings of causes such as heat and cold was criticised by Aristotle in Book II of Physics.[28] He posited natural teleology in its place. He believed that form was achieved for a purpose, citing the regularity of heredity in species as proof.[29][30] Nevertheless, he acceded that new types of animals, monstrosities (τερας), can occur in very rare instances (Generation of Animals, Book IV).[31] As quoted in Darwin's The Origin of Species (1872), Aristotle considered whether different forms (e.g., of teeth) might have appeared accidentally, but only the useful forms survived:

So what hinders the different parts [of the body] from having this merely accidental relation in nature? as the teeth, for example, grow by necessity, the front ones sharp, adapted for dividing, and the grinders flat, and serviceable for masticating the food; since they were not made for the sake of this, but it was the result of accident. And in like manner as to the other parts in which there appears to exist an adaptation to an end. Wheresoever, therefore, all things together (that is all the parts of one whole) happened like as if they were made for the sake of something, these were preserved, having been appropriately constituted by an internal spontaneity, and whatsoever things were not thus constituted, perished, and still perish.

— Aristotle, Physics, Book II, Chapter 8[32]

But he rejected this possibility in the next paragraph:

...Yet it is impossible that this should be the true view. For teeth and all other natural things either invariably or normally come about in a given way; but of not one of the results of chance or spontaneity is this true. We do not ascribe to chance or mere coincidence the frequency of rain in winter, but frequent rain in summer we do; nor heat in the dog-days, but only if we have it in winter. If then, it is agreed that things are either the result of coincidence or for an end, and these cannot be the result of coincidence or spontaneity, it follows that they must be for an end; and that such things are all due to nature even the champions of the theory which is before us would agree. Therefore action for an end is present in things which come to be and are by nature.

— Aristotle, Physics, Book II, Chapter 8[33]

The struggle for existence was later described by Islamic writer Al-Jahiz in the 9th century.[34][35]

The classical arguments were reintroduced in the 18th century by Pierre Louis Maupertuis[36] and others, including Charles Darwin's grandfather Erasmus Darwin. While these forerunners had an influence on Darwinism, they later had little influence on the trajectory of evolutionary thought after Charles Darwin.

Until the early 19th century, the prevailing view in Western societies was that differences between individuals of a species were uninteresting departures from their Platonic idealism (or typus) of created kinds. However, the theory of uniformitarianism in geology promoted the idea that simple, weak forces could act continuously over long periods of time to produce radical changes in the Earth's landscape. The success of this theory raised awareness of the vast scale of geological time and made plausible the idea that tiny, virtually imperceptible changes in successive generations could produce consequences on the scale of differences between species.

Early 19th-century evolutionists such as Jean-Baptiste Lamarck suggested the inheritance of acquired characteristics as a mechanism for evolutionary change; adaptive traits acquired by an organism during its lifetime could be inherited by that organism's progeny, eventually causing transmutation of species.[37] This theory has come to be known as Lamarckism and was an influence on the anti-genetic ideas of the Stalinist Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko.[38]

Between 1835 and 1837, zoologist Edward Blyth also contributed specifically to the area of variation, artificial selection, and how a similar process occurs in nature (see Edward Blyth#On natural selection). In fact, Charles Darwin showed his high regards for Blyth's ideas in the first chapter on variation of On the Origin of Species that he wrote, "Mr. Blyth, whose opinion, from his large and varied stores of knowledge, I should value more than that of almost any one, ..."[39]

Darwin's theory

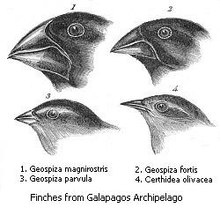

In 1859, Charles Darwin set out his theory of evolution by natural selection as an explanation for adaptation and speciation. He defined natural selection as the "principle by which each slight variation [of a trait], if useful, is preserved."[40] The concept was simple but powerful: individuals best adapted to their environments are more likely to survive and reproduce. As long as there is some variation between them and that variation is heritable, there will be an inevitable selection of individuals with the most advantageous variations. If the variations are heritable, then differential reproductive success will lead to a progressive evolution of particular populations of a species, and populations that evolve to be sufficiently different eventually become different species.[41]

Darwin's ideas were inspired by the observations that he had made on the second voyage of HMS Beagle (1831–1836), and by the work of a political economist, the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, who in An Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), noted that population (if unchecked) increases exponentially, whereas the food supply grows only arithmetically; thus, inevitable limitations of resources would have demographic implications, leading to a "struggle for existence."[42] When Darwin read Malthus in 1838 he was already primed by his work as a naturalist to appreciate the "struggle for existence" in nature and it struck him that as population outgrew resources, "favourable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavourable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species."[43]

Here is Darwin's own summary of the idea, which can be found in the fourth chapter of On the Origin of Species:

- If during the long course of ages and under varying conditions of life, organic beings vary at all in the several parts of their organisation, and I think this cannot be disputed; if there be, owing to the high geometrical powers of increase of each species, at some age, season, or year, a severe struggle for life, and this certainly cannot be disputed; then, considering the infinite complexity of the relations of all organic beings to each other and to their conditions of existence, causing an infinite diversity in structure, constitution, and habits, to be advantageous to them, I think it would be a most extraordinary fact if no variation ever had occurred useful to each being's own welfare, in the same way as so many variations have occurred useful to man. But if variations useful to any organic being do occur, assuredly individuals thus characterised will have the best chance of being preserved in the struggle for life; and from the strong principle of inheritance they will tend to produce offspring similarly characterised. This principle of preservation, I have called, for the sake of brevity, Natural Selection.[44]

Once he had his theory "by which to work," Darwin was meticulous about gathering and refining evidence as his "prime hobby" before making his idea public. He was in the process of writing his "big book" to present his researches when the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace independently conceived of the principle and described it in an essay he sent to Darwin to forward to Charles Lyell. Lyell and Joseph Dalton Hooker decided (without Wallace's knowledge) to present his essay together with unpublished writings that Darwin had sent to fellow naturalists, and On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection was read to the Linnean Society of London announcing co-discovery of the principle in July 1858.[45] Darwin published a detailed account of his evidence and conclusions in On the Origin of Species in 1859. In the 3rd edition of 1861 Darwin acknowledged that others—a notable one being William Charles Wells in 1813, and Patrick Matthew in 1831—had proposed similar ideas, but had neither developed them nor presented them in notable scientific publications.[46]

Darwin thought of natural selection by analogy to how farmers select crops or livestock for breeding, which he called "artificial selection"; in his early manuscripts he referred to a Nature, which would do the selection. At the time, other mechanisms of evolution such as evolution by genetic drift were not yet explicitly formulated, and Darwin believed that selection was likely only part of the story: "I am convinced that Natural Selection has been the main but not exclusive means of modification."[47] In a letter to Charles Lyell in September 1860, Darwin regretted the use of the term "Natural Selection," preferring the term "Natural Preservation."[48]

For Darwin and his contemporaries, natural selection was in essence synonymous with evolution by natural selection. After the publication of On the Origin of Species, educated people generally accepted that evolution had occurred in some form. However, natural selection remained controversial as a mechanism, partly because it was perceived to be too weak to explain the range of observed characteristics of living organisms, and partly because even supporters of evolution balked at its "unguided" and non-progressive nature,[49] a response that has been characterised as the single most significant impediment to the idea's acceptance.[50]

However, some thinkers enthusiastically embraced natural selection; after reading Darwin, Herbert Spencer introduced the term survival of the fittest, which became a popular summary of the theory.[51] The fifth edition of On the Origin of Species published in 1869 included Spencer's phrase as an alternative to natural selection, with credit given: "But the expression often used by Mr. Herbert Spencer of the Survival of the Fittest is more accurate, and is sometimes equally convenient."[52] Although the phrase is still often used by non-biologists, modern biologists avoid it because it is tautological if "fittest" is read to mean "functionally superior" and is applied to individuals rather than considered as an averaged quantity over populations.[53]

Modern evolutionary synthesis

Natural selection relies crucially on the idea of heredity, but developed before the basic concepts of genetics. Although the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel, the father of modern genetics, was a contemporary of Darwin's, his work would lie in obscurity until the early 20th century. Only after the 20th-century integration of Darwin's theory of evolution with a complex statistical appreciation of Gregor Mendel's "re-discovered" laws of inheritance did scientists generally come to accept natural selection.

The work of Ronald Fisher (who developed the required mathematical language and wrote The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection (1930)),[8] J. B. S. Haldane (who introduced the concept of the "cost" of natural selection),[54] Sewall Wright (who elucidated the nature of selection and adaptation),[55] Theodosius Dobzhansky (who established the idea that mutation, by creating genetic diversity, supplied the raw material for natural selection: see Genetics and the Origin of Species (1937)),[56] William D. Hamilton (who conceived of kin selection), Ernst Mayr (who recognised the key importance of reproductive isolation for speciation: see Systematics and the Origin of Species (1942))[57] and many others together formed the modern evolutionary synthesis. This synthesis cemented natural selection as the foundation of evolutionary theory, where it remains today.

Genetic basis of natural selection

The idea of natural selection predates the understanding of genetics. We now have a much better idea of the biology underlying heritability, which is the basis of natural selection.

Genotype and phenotype

Natural selection acts on an organism's phenotype, or physical characteristics. Phenotype is determined by an organism's genetic make-up (genotype) and the environment in which the organism lives. Often, natural selection acts on specific traits of an individual, and the terms phenotype and genotype are used narrowly to indicate these specific traits.

When different organisms in a population possess different versions of a gene for a certain trait, each of these versions is known as an allele. It is this genetic variation that underlies phenotypic traits. A typical example is that certain combinations of genes for eye colour in humans that, for instance, give rise to the phenotype of blue eyes. (On the other hand, when all the organisms in a population share the same allele for a particular trait, and this state is stable over time, the allele is said to be fixed in that population.)

Some traits are governed by only a single gene, but most traits are influenced by the interactions of many genes. A variation in one of the many genes that contributes to a trait may have only a small effect on the phenotype; together, these genes can produce a continuum of possible phenotypic values.[58]

Directionality of selection

When some component of a trait is heritable, selection will alter the frequencies of the different alleles, or variants of the gene that produces the variants of the trait. Selection can be divided into three classes, on the basis of its effect on allele frequencies.[59]

Directional selection occurs when a certain allele has a greater fitness than others, resulting in an increase of its frequency. This process can continue until the allele is fixed and the entire population shares the fitter phenotype. It is directional selection that is illustrated in the antibiotic resistance example above.

Far more common is stabilizing selection (commonly confused with purifying selection[60][61]), which lowers the frequency of alleles that have a deleterious effect on the phenotype – that is, produce organisms of lower fitness. This process can continue until the allele is eliminated from the population. Purifying selection conserves functional genetic features, such as protein-coding genes or regulatory sequences, over time by selective pressure against deleterious variants.

A number of forms of balancing selection exist, which do not result in fixation, but maintain an allele at intermediate frequencies in a population. This can occur in diploid species (that is, those that have homologous pairs of chromosomes) when heterozygote individuals, who have different alleles on each chromosome at a single genetic locus, have a higher fitness than homozygote individuals that have two of the same alleles. This is called heterozygote advantage or over-dominance, of which the best-known example is the resistance to malaria observed in heterozygous humans who carry only one copy of the gene for sickle-cell anaemia. Maintenance of allelic variation can also occur through disruptive or diversifying selection, which favours genotypes that depart from the average in either direction (that is, the opposite of over-dominance), and can result in a bimodal distribution of trait values. Finally, balancing selection can occur through frequency-dependent selection, where the fitness of one particular phenotype depends on the distribution of other phenotypes in the population. The principles of game theory have been applied to understand the fitness distributions in these situations, particularly in the study of kin selection and the evolution of reciprocal altruism.[62][63]

Selection and genetic variation

A portion of all genetic variation is functionally neutral in that it produces no phenotypic effect or significant difference in fitness; the hypothesis that this variation accounts for a large fraction of observed genetic diversity is known as the neutral theory of molecular evolution and was originated by Motoo Kimura. When genetic variation does not result in differences in fitness, selection cannot directly affect the frequency of such variation. As a result, the genetic variation at those sites will be higher than at sites where variation does influence fitness.[59] However, after a period with no new mutation, the genetic variation at these sites will be eliminated due to genetic drift.

Mutation–selection balance

Natural selection results in the reduction of genetic variation through the elimination of maladapted individuals and consequently of the mutations that caused the maladaptation. At the same time, new mutations occur, resulting in a Mutation–selection balance. The exact outcome of the two processes depends both on the rate at which new mutations occur and on the strength of the natural selection, which is a function of how unfavourable the mutation proves to be. Consequently, changes in the mutation rate or the selection pressure will result in a different Mutation–selection balance.

Genetic linkage

Genetic linkage occurs when the loci of two alleles are linked, or in close proximity to each other on the chromosome. During the formation of gametes, recombination of the genetic material results in reshuffling of the alleles. However, the chance that such a reshuffle occurs between two alleles depends on the distance between those alleles; the closer the alleles are to each other, the less likely it is that such a reshuffle will occur. Consequently, when selection targets one allele, this automatically results in selection of the other allele as well; through this mechanism, selection can have a strong influence on patterns of variation in the genome.

Selective sweeps occur when an allele becomes more common in a population as a result of positive selection. As the prevalence of one allele increases, linked alleles can also become more common, whether they are neutral or even slightly deleterious. This is called genetic hitchhiking. A strong selective sweep results in a region of the genome where the positively selected haplotype (the allele and its neighbours) are in essence the only ones that exist in the population.

Whether a selective sweep has occurred or not can be investigated by measuring linkage disequilibrium, or whether a given haplotype is overrepresented in the population. Normally, genetic recombination results in a reshuffling of the different alleles within a haplotype, and none of the haplotypes will dominate the population. However, during a selective sweep, selection for a specific allele will also result in selection of neighbouring alleles. Therefore, the presence of a block of strong linkage disequilibrium might indicate that there has been a 'recent' selective sweep near the centre of the block, and this can be used to identify sites recently under selection.

Background selection is the opposite of a selective sweep. If a specific site experiences strong and persistent purifying selection, linked variation will tend to be weeded out along with it, producing a region in the genome of low overall variability. Because background selection is a result of deleterious new mutations, which can occur randomly in any haplotype, it does not produce clear blocks of linkage disequilibrium, although with low recombination it can still lead to slightly negative linkage disequilibrium overall.[64]

Competition

In the context of natural selection, competition is an interaction between organisms or species in which the fitness of one is lowered by the presence of another. Limited supply of at least one resource (such as food, water, and territory) used by both can be a factor.[65] Competition; both within and between species is an important topic in ecology, especially community ecology. Competition is one of many interacting biotic and abiotic factors that affect community structure. Competition among members of the same species is known as intraspecific competition, while competition between individuals of different species is known as interspecific competition. Competition is not always straightforward, and can occur in both a direct and indirect fashion.[66]

According to the competitive exclusion principle, species less suited to compete for resources should either adapt or die out, although competitive exclusion is rarely found in natural ecosystems. According to evolutionary theory, this competition within and between species for resources plays a very relevant role in natural selection, however, competition may play less of a role than expansion among larger clades,[67] this is termed the 'Room to Roam' hypothesis.[66]

In evolutionary contexts, competition is related to the concept of r/K selection theory, which relates to the selection of traits which promote success in particular environments. The theory originates from work on island biogeography by the ecologists Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson.[68]

In r/K selection theory, selective pressures are hypothesised to drive evolution in one of two stereotyped directions: r- or K-selection.[69] These terms, r and K, are derived from standard ecological algebra, as illustrated in the simple Verhulst equation of population dynamics:[70]

where r is the growth rate of the population (N), and K is the carrying capacity of its local environmental setting. Typically, r-selected species exploit empty niches, and produce many offspring, each of whom has a relatively low probability of surviving to adulthood. In contrast, K-selected species are strong competitors in crowded niches, and invest more heavily in much fewer offspring, each of whom has a relatively high probability of surviving to adulthood.

Impact of the idea

Darwin's ideas, along with those of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, had a profound influence on 19th century thought. Perhaps the most radical claim of the theory of evolution through natural selection is that "...elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, ..." evolved from the simplest forms of life by a few simple principles.[71] This claim inspired some of Darwin's most ardent supporters—and provoked the most profound opposition. The radicalism of natural selection, according to Stephen Jay Gould, lay in its power to "dethrone some of the deepest and most traditional comforts of Western thought."[72] In particular, it challenged long-standing beliefs in such concepts as a special and exalted place for humans in the natural world and a benevolent creator whose intentions were reflected in nature's order and design.

In the words of the philosopher Daniel Dennett, "Darwin's dangerous idea" of evolution by natural selection is a "universal acid," which cannot be kept restricted to any vessel or container, as it soon leaks out, working its way into ever-wider surroundings.[73] Thus, in the last decades, the concept of natural selection has spread from evolutionary biology into virtually all disciplines, including evolutionary computation, quantum Darwinism, evolutionary economics, evolutionary epistemology, evolutionary psychology, and cosmological natural selection. This unlimited applicability has been called universal Darwinism.

Emergence of natural selection

How life originated from inorganic matter (abiogensis) remains an unresolved problem in biology. One prominent hypothesis is that life first appeared in the form of short self-replicating RNA polymers.[74] (see RNA world hypothesis) On this view, “life” may have come into existence when RNA chains first experienced the basic conditions, as conceived by Charles Darwin, for natural selection to operate. These conditions are: heritability, variation of type, and competition for limited resources. Fitness of an early RNA replicator (its per capita rate of increase) would likely have been a function of adaptive capacities that were intrinsic (i.e., determined by the nucleotide sequence) and the availability of resources.[75][76] The three primary adaptive capacities could logically have been: (1) the capacity to replicate with moderate fidelity (giving rise to both heritability and variation of type), (2) the capacity to avoid decay, and (3) the capacity to acquire and process resources.[75][76] These capacities would have been determined initially by the folded configurations (including those configurations with ribozyme activity) of the RNA replicators that, in turn, would have been encoded in their individual nucleotide sequences.[77] Competitive success among different RNA replicators would have depended on the relative values of their adaptive capacities.

Cell and molecular biology

In 1881, Wilhelm Roux, a founder of modern embryology, published Der Kampf der Theile im Organismus (The Struggle of Parts in the Organism) in which he suggested that the development of an organism results from a Darwinian competition between the parts of the embryo, occurring at all levels, from molecules to organs.[78] In recent years, a modern version of this theory has been proposed by Jean-Jacques Kupiec. According to this cellular Darwinism, Stochasticity at the molecular level generates diversity in cell types whereas cell interactions impose a characteristic order on the developing embryo.[79]

Social and psychological theory

The social implications of the theory of evolution by natural selection also became the source of continuing controversy. Friedrich Engels, a German political philosopher and co-originator of the ideology of communism, wrote in 1872 that "Darwin did not know what a bitter satire he wrote on mankind, and especially on his countrymen, when he showed that free competition, the struggle for existence, which the economists celebrate as the highest historical achievement, is the normal state of the animal kingdom."[80] Interpretation[by whom?] of natural selection, by Herbert Spencer and Francis Galton as necessarily "progressive," leading to increasing "advances" in intelligence and civilisation, was used[by whom?] as a justification for colonialism and policies of eugenics, as well as to support broader sociopolitical positions now described as social Darwinism.[citation needed] Konrad Lorenz won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973 for his analysis of animal behaviour in terms of the role of natural selection (particularly group selection). However, in Germany in 1940, in writings that he subsequently disowned, he used the theory as a justification for policies of the Nazi state. He wrote "... selection for toughness, heroism, and social utility...must be accomplished by some human institution, if mankind, in default of selective factors, is not to be ruined by domestication-induced degeneracy. The racial idea as the basis of our state has already accomplished much in this respect."[81] Others have developed ideas that human societies and culture evolve by mechanisms analogous to those that apply to evolution of species.[82]

More recently, work among anthropologists and psychologists has led to the development of sociobiology and later of evolutionary psychology, a field that attempts to explain features of human psychology in terms of adaptation to the ancestral environment. The most prominent example of evolutionary psychology, notably advanced in the early work of Noam Chomsky and later by Steven Pinker, is the hypothesis that the human brain has adapted to acquire the grammatical rules of natural language.[83] Other aspects of human behaviour and social structures, from specific cultural norms such as incest avoidance to broader patterns such as gender roles, have been hypothesised to have similar origins as adaptations to the early environment in which modern humans evolved. By analogy to the action of natural selection on genes, the concept of memes—"units of cultural transmission," or culture's equivalents of genes undergoing selection and recombination—has arisen, first described in this form by Richard Dawkins in 1976[84] and subsequently expanded upon by philosophers such as Daniel Dennett as explanations for complex cultural activities, including human consciousness.[85]

Information and systems theory

In 1922, Alfred J. Lotka proposed that natural selection might be understood as a physical principle that could be described in terms of the use of energy by a system,[86] a concept that was later developed by Howard Odum as the maximum power principle whereby evolutionary systems with selective advantage maximise the rate of useful energy transformation. Such concepts are sometimes relevant in the study of applied thermodynamics.

The principles of natural selection have inspired a variety of computational techniques, such as "soft" artificial life, that simulate selective processes and can be highly efficient in 'adapting' entities to an environment defined by a specified fitness function.[87] For example, a class of heuristic optimisation algorithms known as genetic algorithms, pioneered by John Henry Holland in the 1970s and expanded upon by David E. Goldberg,[88] identify optimal solutions by simulated reproduction and mutation of a population of solutions defined by an initial probability distribution.[89] Such algorithms are particularly useful when applied to problems whose energy landscape is very rough or has many local minima.

Notes and references

References

- ^ Zimmer & Emlen 2013

- ^ Hall, Brian K.; Hallgrímsson, Benedikt (2008). Strickberger's Evolution (4th ed.). Jones and Bartlett. pp. 4–6.

- ^ Miller 2000, p. 8

- ^ Arnqvist, Göran; Rowe, Locke (2005). Sexual Conflict. Princeton University Press. pp. 14–43. ISBN 0-691-12218-0.

- ^ "Teleological Notions in Biology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 18 May 2003. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ a b Darwin 1859

- ^ Miller, Kenneth R. (August 1999). "The Peppered Moth – An Update". millerandlevine.com. Rehoboth, MA: Miller And Levine Biology. Retrieved 2011-04-13.

- ^ a b Fisher 1930

- ^ Works employing or describing this usage:

- ^ Works employing or describing this usage:

- Haldane 1954

- Lande, Russell; Arnold, Stevan J. (November 1983). "The Measurement of Selection on Correlated Characters". Evolution. 37 (6). New York: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution: 1210–1226. doi:10.2307/2408842. JSTOR 2408842.

- Futuyma 2005

- ^ Sober 1993

- ^ Christiansen 1984, pp. 65–79

- ^ Mayr 2006

- ^ Andersson 1994

- ^ Eens, Marcel; Pinxten, Rianne (October 5, 2000). "Sex-role reversal in vertebrates: behavioural and endocrinological accounts". Behavioural Processes. 51 (1–3). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 135–147. doi:10.1016/S0376-6357(00)00124-8. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 11074317.

- ^ Barlow, George W. (March 2005). "How Do We Decide that a Species is Sex-Role Reversed?". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 80 (1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 28–35. doi:10.1086/431022. ISSN 0033-5770. PMID 15884733.

- ^ Schito, Gian C. (March 2006). "The importance of the development of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 12 (Suppl s1). Blackwell Synergy on behalf of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: 3–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01343.x. ISSN 1469-0691. PMID 16445718.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Charlat, Sylvain; Hornett, Emily A.; Fullard, James H.; et al. (July 13, 2007). "Extraordinary Flux in Sex Ratio". Science. 317 (5835). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 214. doi:10.1126/science.1143369. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17626876.

- ^ Kryukov, Gregory V.; Schmidt, Steffen; Sunyaev, Shamil (August 1, 2005). "Small fitness effect of mutations in highly conserved non-coding regions". Human Molecular Genetics. 14 (15). Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2221–2229. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi226. ISSN 0964-6906. PMID 15994173.

- ^ Bejerano, Gill; Pheasant, Michael; Makunin, Igor; et al. (May 28, 2004). "Ultraconserved Elements in the Human Genome". Science. 304 (5675). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1321–1325. doi:10.1126/science.1098119. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15131266.

- ^ Eyre-Walker, Adam; Woolfit, Megan; Phelps, Ted (June 2006). "The Distribution of Fitness Effects of New Deleterious Amino Acid Mutations in Humans". Genetics. 173 (2). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 891–900. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.057570. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1526495. PMID 16547091.

- ^ Galis, Frietson (April 1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes, and cancer". Journal of Experimental Zoology. 285 (1). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell: 19–26. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. ISSN 1932-5223. PMID 10327647.

- ^ Zákány, József; Fromental-Ramain, Catherine; Warot, Xavier; Duboule, Denis (December 9, 1997). "Regulation of number and size of digits by posterior Hox genes: A dose-dependent mechanism with potential evolutionary implications". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (25). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 13695–13700. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13695. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 28368. PMID 9391088.

- ^ Sanyal, Somes; Jansen, Harry G.; de Grip, Willem J.; Nevo, Eviatar; et al. (July 1990). "The Eye of the Blind Mole Rat, Spalax ehrenbergi. Rudiment With Hidden Function?". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 31 (7). Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology: 1398–1404. ISSN 0146-0404. PMID 2142147. Retrieved 2015-07-28.

- ^ Salzburger, Walter; Baric, Sanja; Sturmbauer, Christian (March 2002). "Speciation via introgressive hybridisation in East African cichlids?". Molecular Ecology. 11 (3). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell: 619–625. doi:10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01438.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 11918795.

- ^ Empedocles 1898, On Nature, Book II

- ^ Lucretius 1916, On the Nature of Things, Book V

- ^ Aristotle, Physics, Book II, Chapters 4 and 8

- ^ Lear 1988, p. 38

- ^ Henry, Devin (September 2006). "Aristotle on the Mechanism of Inheritance" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 39 (3). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media: 425–455. doi:10.1007/s10739-005-3058-y. ISSN 0022-5010. Retrieved 2015-07-30.

- ^ Ariew 2002

- ^ Darwin 1872, p. xiii

- ^ Aristotle, Physics, Book II, Chapter 8

- ^ Zirkle, Conway (April 25, 1941). "Natural Selection before the 'Origin of Species'". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 84 (1). Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society: 71–123. ISSN 0003-049X. JSTOR 984852.

- ^ Agutter & Wheatley 2008, p. 43

- ^ Maupertuis, Pierre Louis (1746). ["Derivation of the laws of motion and equilibrium from a metaphysical principle"]. Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles Lettres (in French). Berlin: Ambroise Haude: 267–294.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lamarck 1809

- ^ Joravsky, David (January 1959). "Soviet Marxism and Biology before Lysenko". Journal of the History of Ideas. 20 (1). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press: 85–104. doi:10.2307/2707968. ISSN 0022-5037.

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 18

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 61

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 5

- ^ Malthus 1798

- ^ Darwin 1958, p. 120

- ^ Darwin 1859, pp. 126–127

- ^ Wallace 1871

- ^ Darwin 1861, p. xiii

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 6

- ^ Darwin, Charles (September 28, 1860). "Darwin, C. R. to Lyell, Charles". Darwin Correspondence Project. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Library. Letter 2931. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

- ^ Eisley 1958

- ^ Kuhn 1996

- ^ Darwin, Charles (July 5, 1866). "Darwin, C. R. to Wallace, A. R." Darwin Correspondence Project. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Library. Letter 5145. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- Stucke, Maurice E. (Summer 2008). "Better Competition Advocacy" (PDF). St. John's Law Review. 82 (3). Jamaica, NY: St. John's University School of Law: 951–1036. ISSN 2168-8796. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

This survival of the fittest, which I have here sought to express in mechanical terms, is that which Mr. Darwin has called 'natural selection, or the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.'

—Herbert Spencer, Principles of Biology (1864), vol. 1, pp. 444–445

- Stucke, Maurice E. (Summer 2008). "Better Competition Advocacy" (PDF). St. John's Law Review. 82 (3). Jamaica, NY: St. John's University School of Law: 951–1036. ISSN 2168-8796. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ^ Darwin 1872, p. 49.

- ^ Mills, Susan K.; Beatty, John H. (1979). "The Propensity Interpretation of Fitness" (PDF). Philosophy of Science. 46. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Philosophy of Science Association: 263–286. doi:10.1086/288865. ISSN 0031-8248.

- ^ Haldane 1932

- Haldane, J. B. S. (December 1957). "The Cost of Natural Selection" (PDF). Journal of Genetics. 55 (3): 511–524. doi:10.1007/BF02984069. ISSN 0022-1333. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ^ Wright, Sewall (1932). "The roles of mutation, inbreeding, crossbreeding and selection in evolution". Proceedings of the VI International Congress of Genetrics. 1: 356–366. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- ^ Dobzhansky 1937

- ^ Mayr 1942

- ^ Falconer & Mackay 1996

- ^ a b Rice 2004, See esp. chpt. 5 and 6 for a quantitative treatment

- ^ Lemey, Salemi & Vandamme 2009

- ^ Loewe, Laurence (2008). "Negative Selection". Nature Education. Cambridge, MA: Nature Publishing Group. OCLC 310450541. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ^ Hamilton, William D. (July 1964). "The genetical evolution of social behaviour. II". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 7 (1). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 17–52. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 5875340.

- ^ Trivers, Robert L. (March 1971). "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 46 (1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 35–57. doi:10.1086/406755. ISSN 0033-5770. JSTOR 2822435.

- ^ Keightley, Peter D.; Otto, Sarah P. (September 7, 2006). "Interference among deleterious mutations favours sex and recombination in finite populations". Nature. 443 (7107). London: Nature Publishing Group: 89–92. doi:10.1038/nature05049. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16957730.

- ^ Begon, Townsend & Harper 1996

- ^ a b Sahney, Sarda; Benton, Michael J.; Ferry, Paul A. (August 23, 2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land" (PDF). Biology Letters. 6 (4). London: Royal Society Publishing: 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

- ^ Jardine, Phillip E.; Janis, Christine M.; Sahney, Sarda; Benton, Michael J. (December 1, 2012). "Grit not grass: Concordant patterns of early origin of hypsodonty in Great Plains ungulates and Glires". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 365–366. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.09.001. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ MacArthur & Wilson 2001

- ^ Pianka, Eric R. (November–December 1970). "On r- and K-Selection". The American Naturalist. 104 (940). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press on behalf of the American Society of Naturalists: 592–597. doi:10.1086/282697. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2459020.

- ^ Verhulst, Pierre François (1838). "Notice sur la loi que la population suit dans son accroissement". Correspondance mathématique et physique (in French). 10. Brussels, Belgium: Société belge de librairie: 113–121. OCLC 490225808. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ^ Darwin 1859, p. 489

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (June 12, 1997). "Darwinian Fundamentalism". The New York Review of Books. 44 (10). New York: Rea S. Hederman. ISSN 0028-7504. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- ^ Dennett 1995

- ^ Eigen, Manfred; Gardiner, William; Schuster, Peter; et al. (April 1981). "The Origin of Genetic Information". Scientific American. 244 (4). Stuttgart: Georg von Holtzbrinck Publishing Group: 88–92, 96, et passim. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0481-88. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 6164094.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Harris; Byerly, Henry C.; Hopf, Frederick A.; et al. (June 1983). "The Darwinian Dynamic". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 58 (2). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press: 185–207. doi:10.1086/413216. ISSN 0033-5770. JSTOR 2828805.

- ^ a b Michod 1999

- ^ Orgel, Leslie E. (1987). "Evolution of the Genetic Apparatus: A Review". Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 52. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 9–16. doi:10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.004. ISSN 0091-7451. PMID 2456886.

- ^ Roux 1881

- ^ Kupiec, Jean-Jacques [in French] (May 3, 2010). "Cellular Darwinism (stochastic gene expression in cell differentiation and embryo development)". SciTopics. Archived from the original on 2010-08-04. Retrieved 2015-08-11.

- ^ Engels 1964

- ^ Eisenberg, Leon (September 2005). "Which image for Lorenz?". American Journal of Psychiatry (Letter to the editor). 162 (9). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association: 1760. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1760. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 16135651. Eisenberg quoting translation of Durch Domestikation verursachte Störungen arteigenen Verhaltens (1940, p. 2) by Konrad Lorenz.

- ^ For example: Wilson 2002

- ^ Pinker 1995

- ^ Dawkins 1976, p. 192

- ^ Dennett 1991

- ^ Lotka, Alfred J. (June 1922). "Contribution to the energetics of evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 8 (6). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 147–151. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.6.147. PMC 1085052. PMID 16576642.

- Lotka, Alfred J. (June 1922). "Natural selection as a physical principle". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 8 (6). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 151–154. doi:10.1073/pnas.8.6.151. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1085053. PMID 16576643.

- ^ Kauffman 1993

- ^ Goldberg 1989

- ^ Mitchell 1996

Bibliography

- Agutter, Paul S.; Wheatley, Denys N. (2008). Thinking about Life: The History and Philosophy of Biology and Other Sciences. Dordrecht, the Netherlands; London: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-8865-0. LCCN 2008933269. OCLC 304561132.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Andersson, Malte (1994). Sexual Selection. Monographs in Behavior and Ecology. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00057-3. LCCN 93033276. OCLC 28891551.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ariew, André (2002). "Platonic and Aristotelian Roots of Teleological Arguments" (PDF). In Ariew, André; Cummins, Robert; Perlman, Mark (eds.). Functions: New Essays in the Philosophy of Psychology and Biology. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-824103-8. LCCN 2002020184. OCLC 48965141.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|archive-url=requires|url=(help);|chapter-format=requires|chapter-url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Aristotle. Physics. Translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye. The Internet Classics Archive. OCLC 54350394.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Begon, Michael; Townsend, Colin R.; Harper, John L. (1996). Ecology: Individuals, Populations and Communities (3rd ed.). Oxford; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0-632-03801-2. LCCN 95024627. OCLC 32893848.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Christiansen, Freddy B. (1984). "The Definition and Measurement of Fitness". In Shorrocks, Bryan (ed.). Evolutionary Ecology: The 23rd Symposium of the British Ecological Society, Leeds, 1982. Symposium of the British Ecological Society. Vol. 23. Oxford; Boston: Blackwell Scientific Publications. ISBN 0-632-01189-0. LCCN 85106855. OCLC 12586581.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Modified from Christiansen by adding survival selection in the reproductive phase. - Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 06017473. OCLC 741260650.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) The book is available from The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Retrieved 2015-07-23. - Darwin, Charles (1861). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (3rd ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 04001284. OCLC 550913. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Darwin, Charles (1872). The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (6th ed.). London: John Murray. OCLC 1185571. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Darwin, Charles (1958). Barlow, Nora (ed.). The Autobiography of Charles Darwin, 1809–1882: With original omissions restored; Edited and with Appendix and Notes by his grand-daughter, Nora Barlow. London: Collins. LCCN 93017940. OCLC 869541868. Retrieved 2015-07-23.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dawkins, Richard (1976). The Selfish Gene. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-857519-X. LCCN 76029168. OCLC 2681149.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dennett, Daniel C. (1991). Consciousness Explained (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-18065-3. LCCN 91015614. OCLC 23648691.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dennett, Daniel C. (1995). Darwin's Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80290-2. LCCN 94049158. OCLC 31867409.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobzhansky, Theodosius (1937). Genetics and the Origin of Species. Columbia University Biological Series. New York: Columbia University Press. LCCN 37033383. OCLC 766405.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Eisley, Loren (1958). Darwin's Century: Evolution and the Men Who Discovered It (1st ed.). Garden City, NY: Doubleday. LCCN 58006638. OCLC 168989.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Empedocles (1898). "Empedokles". In Fairbanks, Arthur (ed.). The First Philosophers of Greece. Translation by Arthur Fairbanks. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Ltd. LCCN 03031810. OCLC 1376248.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) The First Philosophers of Greece at the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-07-29. - Endler, John A. (1986). Natural Selection in the Wild. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08386-X. LCCN 85042683. OCLC 12262762.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Engels, Friedrich (1964) [1883]. Dialectics of Nature. 1939 preface by J. B. S. Haldane (3rd rev. ed.). Moscow, USSR: Progress Publishers. LCCN 66044448. OCLC 807047245.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) The book is available from the Marxist Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-08-04. - Falconer, Douglas S.; Mackay, Trudy F. C. (1996). Introduction to Quantitative Genetics (4th ed.). Harlow, England: Longman. ISBN 0-582-24302-5. OCLC 824656731.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fisher, Ronald Aylmer (1930). The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. LCCN 30029177. OCLC 493745635.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Futuyma, Douglas J. (2005). Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-187-2. LCCN 2004029808. OCLC 57311264.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goldberg, David E. (1989). Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization and Machine Learning. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-201-15767-5. LCCN 88006276. OCLC 17674450.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Haldane, J. B. S. (1932). The Causes of Evolution. London; New York: Longmans, Green & Co. LCCN 32033284. OCLC 5006266.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) "This book is based on a series of lectures delivered in January 1931 at the Prifysgol Cymru, Aberystwyth, and entitled 'A re-examination of Darwinism'." - Haldane, J. B. S. (1954). "The Measurement of Natural Selection". In Montalenti, Giuseppe; Chiarugi, A. (eds.). Atti del IX Congresso Internazionale di Genetica, Bellagio (Como) 24–31 agosto 1953 [Proceedings of the 9th International Congress of Genetics]. Caryologia. Vol. 6 (1953/54) Suppl. Florence, Italy: University of Florence. pp. 480–487. OCLC 9069245.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Kauffman, Stuart (1993). The Origins of Order: Self-Organisation and Selection in Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507951-5. LCCN 91011148. OCLC 23253930.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1809). Philosophie Zoologique. Paris: Dentu et L'Auteur. OCLC 2210044.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Philosophie zoologique (1809) at the Internet Archive. Retrieved 2015-07-31. - Lear, Jonathan (1988). Aristotle: The Desire to Understand. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-34762-9. LCCN 87020284. OCLC 16352317.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuhn, Thomas S. (1996). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (3rd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45808-3. LCCN 96013195. OCLC 34548541.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lemey, Philippe; Salemi, Marco; Vandamme, Anne-Mieke, eds. (2009). The Phylogenetic Handbook: A Practical Approach to Phylogenetic Analysis and Hypothesis Testing (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-73071-6. LCCN 2009464132. OCLC 295002266.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lucretius (1916). "Book V". In Leonard, William Ellery (ed.). De Rerum Natura. Translated by William Ellery Leonard. Medford/Somerville, MA: Tufts University. OCLC 33233743.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacArthur, Robert H.; Wilson, Edward O. (2001) [Originally published 1967]. The Theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton Landmarks in Biology. New preface by Edward O. Wilson. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08836-5. LCCN 00051495. OCLC 45202069.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Malthus, Thomas Robert (1798). An Essay on the Principle of Population, As It Affects the Future Improvement of Society: with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers (1st ed.). London: J. Johnson. LCCN 46038215. OCLC 65344349.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) The book is available here from Frank Elwell, Rogers State University. Retrieved 2008-11-08. - Mayr, Ernst (1942). Systematics and the Origin of Species from the Viewpoint of a Zoologist. Columbia Biological Series. Vol. 13. New York: Columbia University Press. LCCN 43001098. OCLC 766053.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mayr, Ernst (2006) [Originally published 1972; Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Co.]. "Sexual Selection and Natural Selection". In Campbell, Bernard G. (ed.). Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man: The Darwinian Pivot. New Brunswick, NJ: AldineTransaction. ISBN 0-202-30845-6. LCCN 2005046652. OCLC 62857839.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Michod, Richard A. (1999). Darwinian Dynamics: Evolutionary Transitions in Fitness and Individuality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02699-8. LCCN 98004166. OCLC 38948118.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, Geoffrey (2000). The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-49516-1. LCCN 00022673. OCLC 43648482.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Melanie (1996). An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms. Complex Adaptive Systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-13316-4. LCCN 95024489. OCLC 42854439.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pinker, Steven (1995) [Originally published 1994; New York: William Morrow and Company]. The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language (1st Harper Perennial ed.). New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-097651-9. LCCN 94039138. OCLC 670524593.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rice, Sean H. (2004). Evolutionary Theory: Mathematical and Conceptual Foundations. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 0-87893-702-1. LCCN 2004008054. OCLC 54988554.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roux, Wilhelm (1881). Der Kampf der Theile im Organismus. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann. OCLC 8200805.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Der Kampf der Theile im Organismus at the Internet Archive Retrieved 2015-08-11. - Sober, Elliott (1993) [Originally published 1984; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press]. The Nature of Selection: Evolutionary Theory in Philosophical Focus. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-76748-5. LCCN 93010367. OCLC 896826726.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wallace, Alfred Russel (1871) [Originally published 1870]. Contributions to the Theory of Natural Selection. A Series of Essays (2nd, with corrections and additions ed.). New York: Macmillan & Co. LCCN agr04000394. OCLC 809350209. Retrieved 2015-08-01.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, George C. (1966). Adaptation and Natural Selection: A Critique of Some Current Evolutionary Thought. Princeton Science Library. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02615-7. LCCN 65017164. OCLC 35230452.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wilson, David Sloan (2002). Darwin's Cathedral: Evolution, Religion, and the Nature of Society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-90134-3. LCCN 2002017375. OCLC 48777441.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zimmer, Carl; Emlen, Douglas J. (2013). Evolution: Making Sense of Life (1st ed.). Greenwood Village, CO: Roberts and Company Publishers. ISBN 978-1-936221-17-2. LCCN 2012025118. OCLC 767565909.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- For technical audiences

- Bell, Graham (2008). Selection: The Mechanism of Evolution (2nd ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856972-5. LCCN 2007039692. OCLC 170034792.

- Johnson, Clifford (1976). Introduction to Natural Selection. Baltimore, MD: University Park Press. ISBN 0-8391-0936-9. LCCN 76008175. OCLC 2091640.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00613-5. LCCN 2001043556. OCLC 47869352.

- Maynard Smith, John (1993) [Originally published 1958; Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books]. The Theory of Evolution (Canto ed.). Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45128-0. LCCN 93020358. OCLC 27676642.

- Popper, Karl (December 1978). "Natural Selection and the Emergence of Mind". Dialectica. 32 (3–4). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell: 339–355. doi:10.1111/j.1746-8361.1978.tb01321.x. ISSN 0012-2017. Retrieved 2015-08-06.

- Sammut-Bonnici, Tanya; Wensley, Robin (September 2002). "Darwinism, probability and complexity: market-based organizational transformation and change explained through the theories of evolution". International Journal of Management Reviews. 4 (3). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell: 291–315. doi:10.1111/1468-2370.00088. ISSN 1460-8545.

- Sober, Elliott, ed. (1994). Conceptual Issues in Evolutionary Biology (2nd ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-69162-0. LCCN 93008199. OCLC 28150417.