German occupation of the Channel Islands

The Occupation of the Channel Islands refers to the military occupation of the Channel Islands by Germany during World War II which lasted from 30 June 1940 until the Liberation on 9 May 1945. The Channel Islands comprise the crown dependencies of the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey which are not parts of the United Kingdom, and also take in the smaller islands, of Alderney and Sark (part of the bailiwick of Guernsey). These were the only portions of the British Isles to be invaded and occupied by German forces during the war.

Before occupation

Demilitarisation

On 15 June 1940, the British Government decided that the Channel Islands were of no strategic importance and would not be defended. They decided to keep this a secret from the German forces. So, in spite of the reluctance of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the British Government gave up the oldest possession of the Crown "without firing a single shot".[1] The Channel Islands served no purpose to the Germans other than the propaganda value of having occupied some British territory. The "Channel Islands [had] been demilitarised and declared…'an open town' ".[2]

Evacuation

The British Government consulted the islands' elected government representatives, in order to formulate a policy regarding evacuation. Opinion was divided and, without a policy being imposed on the islands, chaos ensued and different policies were adopted by the different islands. The British Government concluded their best policy was to make available as many ships as possible so that islanders had the option to leave if they wanted to. The authorities on Alderney recommended that all islanders evacuate, and nearly all did so; the Dame of Sark encouraged everyone to stay. Guernsey evacuated all children of school age, giving the parents the option of keeping their children with them, or evacuating with their school. In Jersey, the majority of islanders chose to stay.

Invasion

Since the Germans did not realise that the islands had been demilitarised, they approached them with some caution. Reconnaissance flights were inconclusive. On 28 June 1940, they sent a squadron of bombers over the islands and bombed the harbours of Guernsey and Jersey. In St Peter Port, what the reconnaissance mistook for troop carriers were actually trucks lined up to load tomatoes for export to England. Forty-four islanders were killed in the raids.

While the German Army was preparing to land an assault force of two battalions to capture the islands, a reconnaissance pilot landed in Guernsey on 30 June to whom the island officially surrendered. Jersey surrendered on 1 July. Alderney, where only a handful of islanders remained, was occupied on 2 July and a small detachment travelled from Guernsey to Sark, which officially surrendered on 4 July.

Occupation

The German forces quickly consolidated their positions. They brought in infantry, established communications and anti-aircraft defences, established an air service with mainland France and rounded up British servicemen on leave.

Government

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

In Guernsey, the Bailiff, Sir Victor Carey and the States of Guernsey handed overall control to the German authorities. Day-to-day running of island affairs became the responsibility of a Controlling Committee, chaired by Ambrose Sherwill. Scrip (occupation money) was issued in Guernsey to keep the economy going. German military forces used their own scrip for payment of goods and services.

The German authorities changed the Channel Island time zone from GMT to CET in order to bring the islands into line with continental Europe, and the rule of the road was also changed from left to right.

Alderney concentration camps

The Germans built four concentration camps on Alderney. The camps were subcamps of the Neuengamme concentration camp outside Hamburg and each was named after one of the Frisian Islands: Lager Norderney located at Saye, Lager Borkum at Platte Saline, Lager Sylt near the old telegraph tower at La Foulère and Lager Helgoland in the northwest corner of Alderney. The Nazi Organisation Todt operated each subcamp and used forced labour to build bunkers, gun emplacements, air-raid shelters, and concrete fortifications. The camps commenced operating in January 1942 and had a total inmate population of about 6,000.

The Borkum and Helgoland camps were "volunteer" (Hilfswillige) labour camps[3] and the labourers in those camps were treated harshly but marginally better than the inmates at the Sylt and Norderney camps. The prisoners in Lager Sylt and Lager Norderney were slave labourers forced to build the many military fortifications and installations throughout Alderney. Sylt camp held Jewish enforced labourers[4]. Norderney camp housed European (usually Eastern but including Spaniard) and Soviet enforced labourers. Lager Borkum was used for German technicians and "volunteers" from different countries of Europe. Lager Helgoland was filled with Soviet Organisation Todt workers.

In 1942, Lager Norderney, containing Soviet and Polish POWs, and Lager Sylt, holding Jews, were placed under the control of the SS Hauptsturmführer Max List. Over 700 of the inmates lost their lives before the camps were closed and the remaining inmates transferred to Germany in 1944 [4]. (For further information on Alderney concentration camps, see Alderney, a Nazi concentration camp on an island Anglo-Norman[5]; for further information on Nazi treatment of Jews and other people, see The Holocaust.)

Resistance and collaboration

Louisa Gould hid a wireless set and sheltered an escaped Russian prisoner. Betrayed by an informer at the end of 1943, she was arrested and sentenced 22 June 1944. In August 1944 she was transported to Ravensbrück and murdered in the gas chambers there 13 February 1945.[6]

There was no resistance movement in the Channel Islands on the scale of that in mainland France. This has been ascribed to a range of factors including the physical separation of the islands, the density of troops (up to one German for every two islanders), the small size of the islands precluding any hiding places for resistance groups and the absence of the Gestapo from the occupying forces. Moreover, much of the population of military age had joined the British Army already.

Resistance involved passive resistance, acts of minor sabotage, sheltering and aiding escaped slave workers (see, for example, Albert Bedane) and publishing underground newspapers containing news from BBC radio. The islanders also joined in the Churchill's V sign campaign by daubing the letter 'V' (for Victory) over German signs. A widespread form of passive resistance (albeit taking place in secret within the confines of islanders' homes) was the act of listening to BBC radio, which was banned in the first few weeks of the occupation and then (surprisingly given the policy elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe) tolerated for a period before being once again prohibited. Later the ban became even more draconian with all radio listening (even to German stations) being banned by the occupiers backed up by the widespread confiscation of wireless sets. Nevertheless, many islanders successfully hid their radios (or replaced them with homemade crystal sets) and continued listening to the BBC despite the risk of being discovered by the Germans or being informed on by neighbours.[7]

A number of islanders escaped (including Peter Crill), the pace of which increased following D-Day, when conditions in the islands worsened as supply routes to the continent were cut off and the desire to join in the liberation of Europe increased.

The policy of the island governments, acting under instructions from the British government communicated before the occupation, was one of passive co-operation, although this has been criticised (see Bunting), particularly in the treatment of Jews in the islands. The remaining Jews on the islands, often Church of England members with one or two Jewish grandparents, were subjected to the nine Orders Pertaining to Measures Against the Jews , including closing of their businesses (or placing them under Aryan administration), giving up their wirelesses, and staying indoors for all but one hour per day. These measures were administered by the Bailiff and the Aliens Office.[8]

Some island women fraternised with the occupying forces, although this was frowned upon by the majority of islanders, who gave them the derogatory nickname Jerry-bag.

One side-effect of the occupation and local resistance was an increase in the speaking of local languages (Guernesiais in Guernsey and Jerriais in Jersey). As many of the German soldiers were familiar with both English and French, the indigenous languages enjoyed a brief revival as islanders sought to converse without being overheard.

The lack of currency in Jersey led to a request to artist Edmund Blampied to design scrip for the States of Jersey in denominations of 6 pence, 1 shilling, 2 shillings, 10 shillings and 1 pound, which were issued in 1942. A year later he was asked to design six new postage stamps for the island of ½ d to 3 d and, as a sign of resistance, he cleverly incorporated the initials GR in the three penny stamp to display loyalty to King George VI.[9]

British Government reaction

The British Government's reaction to the German invasion was muted, with the Ministry of Information issuing a press release shortly after the Germans landed.

On 6 July 1940, 2nd Lieutenant Hubert Nicolle, a Guernseyman serving with the British Army, was dispatched on a fact-finding mission to Guernsey. He was dropped off the south coast of Guernsey by a submarine and rowed ashore in a canoe under cover of night. This was the first of two visits which Nicolle made to the island. Following the second, he missed his rendezvous and was trapped on the island. After a month and a half in hiding, he gave himself up to the German authorities and was sent to a German prison-of-war camp.

On the night of 14 July 1940, Operation Ambassador, was launched on the German occupied island of Guernsey by men drawn from H Troop of No. 3 Commando under John Durnford-Slater and No.11 Independent Company. The raiders failed to make contact with the German garrison.[10]

In October 1942, there was a British Commando raid on Sark, named Operation Basalt.

In 1943, Vice Admiral Lord Mountbatten proposed a plan to retake the islands named Operation Constellation. The proposed attack was never mounted.

Fortification

As part of the Atlantic Wall, between 1940 and 1945 the occupying German forces and the Organisation Todt constructed fortifications round the coasts of the Channel Islands.

The majority of the workforce constructing bunkers were German soldiers (photo evidence recorded) although around one thousand Russian soldiers were also used as slave labour.

In Alderney, a concentration camp, Lager Sylt, was established to provide slave labour for the fortifications.

The Channel Islands were amongst the most heavily fortified, particularly the island of Alderney which is the closest to France. Hitler had decreed that 10% of the steel and concrete used in the Atlantic Wall go to the Channel Islands. A large number of the German bunkers and batteries can still be seen today throughout the Channel Islands, a number of them have been restored and are now open to the general public to visit.

Deportation

In 1942, the German authorities announced that all residents of the Channel Islands who were not born in the islands, as well as those men who had served as officers in World War I, were to be deported. The majority of them were transported to the southwest of Germany, notably to Ilag V-B at Biberach an der Riss and Ilag VII at Laufen. This deportation decision came directly from Adolf Hitler, as a reprisal for German civilians in Iran[11] being deported and interned. The ratio was twenty Channel Islanders to be interned for every one German interned.

Representation in London

As self-governing Crown Dependencies, the Channel Islands had no elected representatives in the British Parliament. It therefore fell to evacuees and other islanders living in the United Kingdom prior to the occupation to ensure that the islanders were not forgotten. The Jersey Society in London, formed in the 1920s, provided a focal point for exiled Jerseymen. In 1943, a number of influential Guernseymen living in London formed the Guernsey Society to provide a similar focal point and network for Guernsey exiles. Besides relief work, these groups also undertook studies to plan for economic reconstruction and political reform after the end of the war. The pamphlet Notre Île published in London by a committee of Jersey people was influential in the 1948 reform of the constitution of the Bailiwick.

Bertram Falle, a Jerseyman, was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Portsmouth in 1910. Eight times elected to the House of Commons, in 1934 he was raised to the House of Lords with the title of Lord Portsea. During the occupation he represented the interests of islanders and pressed the British government to relieve their plight, especially after the islands were cut off after D-Day.

Committees of émigré Channel Islanders elsewhere in the British Empire also banded together to provide relief for evacuees. For example, Philippe William Luce (writer and journalist, 1882–1966) founded the Vancouver Channel Islands Society in 1940 to raise money for evacuees.

Under siege

During June 1944, the Allied Forces launched the D-Day landings and the liberation of Normandy. They decided to bypass the Channel Islands due to the heavy fortifications constructed by German Forces (see above). However, the consequence of this was that German supply lines for food and other supplies through France were completely severed. The islanders' food supplies were already dwindling, and this made matters considerably worse - the islanders and German forces alike were on the point of starvation.

Churchill's reaction to the plight of the German garrison was to "let 'em rot"[12], even though this meant that the islanders had to rot with them. It took months of protracted negotiations before the International Red Cross ship SS Vega was permitted to relieve the starving islanders in December 1944, bringing Red Cross food parcels, salt and soap, as well as medical and surgical supplies. The Vega made five further trips to the islands before liberation in May 1945.

In 1944, the popular German film actress Lil Dagover arrived on the Channel Islands to entertain German troops on the islands of Jersey and Guernsey with a theatre tour to boost morale.[13]

The Granville Raid occurred on the night of 8 March 1945 – 9 March 1945 when a German raiding force from the Channel Islands successfully landed and brought back supplies to their base.[14]

Liberation and legacy

Liberation

Although plans had been drawn up and proposed by Vice Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, in 1943, for Operation Constellation, a military reconquest of the islands, it was not to be. The Channel Islands were liberated after the German surrender.

On the 8 May 1945 at 10 am, the islanders were informed by the German authorities that the war was over. Churchill made a radio broadcast at 3pm during which he announced that:

- Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight to-night, but in the interests of saving lives the "Cease fire" began yesterday to be sounded all along the front, and our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed to-day.[15]

The following morning, 9 May 1945, HMS Bulldog arrived in St Peter Port, Guernsey and the German forces surrendered unconditionally aboard it at dawn. British forces landed in St Peter Port shortly afterwards, greeted by crowds of joyous but malnourished islanders.

HMS Beagle, which had set out at the same time from Plymouth performed a similar role in liberating Jersey.

It appears that the first place liberated on Jersey might have been the British General Post Office Jersey repeater station. Mr Warder, a GPO linesman, had been stranded on the island during the occupation. He did not wait for the island to be liberated and went to the repeater station where he informed the German officer in charge that he was taking over the building on behalf of the British Post Office.[16]

Aftermath

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

Following the liberation of 1945 allegations against those accused of collaborating with the occupying authorities were investigated. By November 1946, the UK Home Secretary was in a position to inform the UK House of Commons[17] that most of the allegations lacked substance and only 12 cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, but the Director of Public Prosecutions had ruled out prosecutions on insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed to the occupying authorities against their fellow-citizens.[18]

In Jersey and Guernsey, laws[19][20] were passed to retrospectively confiscate the financial gains made by war profiteers and black marketeers, although these measures also affected those who had made legitimate profits during the years of military occupation.

During the occupation, 'Jerry-bags' who had fraternised with German soldiers had aroused indignation among some citizens. In the hours following the liberation, members of the British liberating forces were obliged to intervene to prevent revenge attacks.[21]

For two years after the liberation, Alderney was operated as a communal farm. Craftsmen were paid by their employers, whilst others were paid by the local government out of the profit from the sales of farm produce. Remaining profits were put aside to repay the British Government for repairing and rebuilding the island. Resentment from the local population towards being unable to control their own land acted as a catalyst for the United Kingdom Home Office to set up an enquiry that led to the "Government of Alderney Law 1948", which came into force on 1 January 1949. The law organised the construction and election of the States of Alderney, the justice system and, for the first time in Alderney, the imposition of taxes. Due to the small population of Alderney, it was believed that the island could not be self-sufficient in running the airport and the harbour, as well as in providing an acceptable level of services. The taxes were therefore collected into the general Bailiwick of Guernsey revenue funds (at the same rate as Guernsey) and administered by the States of Guernsey. Guernsey became responsible for providing many governmental functions and services.

Particularly in Guernsey, which evacuated the majority of school-age children ahead of the occupation, one enduring legacy of the occupation has been a contribution to the ongoing loss of the indigenous culture of the island. Many felt that the children "left as Guerns and returned as English". This was particularly felt in the loss of the local dialect - children who were fluent in Guernesiais when they left, found that after 5 years of non-use they had lost much of language.

War crime trials

After World War II, a court-martial case was prepared against ex-SS Hauptsturmführer Max List (the former commandant of Lagers Norderney and Sylt), citing atrocities on Alderney[22]. However, he did not stand trial, and is believed to have lived near Hamburg until his death in the 1980s[23].

Legacy

- Since the end of the occupation, the anniversary of Liberation Day (9 May) has been celebrated as a National holiday. But in Alderney there was no official local population to be liberated, so Alderney celebrates "Homecoming Day" on 15 December to commemorate the return of the evacuated population. The first ship of evacuated citizens from Alderney returned on this day.[24]

- Many islanders and evacuees have published their memoirs and diaries of this period.

- The Channel Islands Occupation Society was formed in order to study and preserve the history of this period.

- A number of documentaries have been made about the Occupation, mixing interviews with participants, both islanders and soldiers, archive footage, photos and manuscripts and modern day filming around the extensive fortifications still in place. These films include:

- High Tide Productions' In Toni's Footsteps: The Channel Island Occupation Remembered- 52min documentary tracing the history of the Occupation following the discovery of a notebook in an attic in Guernsey belonging to a German soldier named Toni Kumpel.

- There have also been a number of TV and film dramas set in the occupied islands:

- Appointment with Venus, a film set on the fictional island of Armorel (based on the island of Sark).

- ITV's Enemy at the Door, set in Guernsey and shown between 1978 and 1980

- A&E's Night of the Fox (1990), set in Jersey shortly before D-Day in 1944.

- ITV's Island at War (2004), a drama set in the fictional Channel Island of St Gregory. It was shown by US TV network PBS as part of their Masterpiece Theatre series in 2005.

- The 2001 film, The Others starring Nicole Kidman was set in Jersey in 1945 just after the end of the occupation.

- A stage play, Dame of Sark by William Douglas-Home is set in the island of Sark during the German Occupation, and is based on the Dame's diaries of this period.

- The following novels have been set in the German-occupied islands:

- Higgins, Jack (1970), A Game for Heroes, New York : Berkley, ISBN 0440132622

- Binding, Tim (1999), Island Madness, London : Picador, ISBN 0-330-35046-3

- Link, Charlotte (2000), Die Rosenzüchterin [The Rose Breeder], condensed ed., Köln : BMG-Wort, ISBN 3-89830-125-7

- Parkin, Lance (1996), Just War, New Doctor Who adventures series, Doctor Who Books, ISBN 0-426-20463-8

- Robinson, Derek (1977), Kramer's War, London : Hamilton, ISBN 0-241-89578-2

- Tickell, Jerrard (1976), Appointment with Venus, London : Kaye and Ward, ISBN 0-7182-1127-8

- Walters, Guy (2005), The Occupation, London : Headline, ISBN 0-7553-2066-2

- Shaffer, Mary Ann and Barrows, Annie (2008),The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, New York : The Dial Press, ISBN 978-0-385-34099-1

- Cone, Libby (2009), War on the Margins, London : Duckworth, ISBN 9780715638767

- The Blockhouse, a film starring Peter Sellers and Charles Aznavour, set in occupied France, was filmed in a German bunker in Guernsey in 1973[25].

- A number of German fortifications have been preserved as museums, including the Underground Hospitals built in Jersey (Höhlgangsanlage 8) and Guernsey[26].

- Liberation Square in St. Helier, Jersey, is now a focal point of the town, and has a sculpture which celebrates the liberation of the island.

Notes

- ^ Hazel R. Knowles Smith, The changing face of the Channel Islands Occupation (2007, Palgrave Macmillan, UK)

- ^ Falla, Frank (1967). The Silent War. Burbridge. ISBN 0450020444..

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Christian Streit: Keine Kameraden: Die Wehrmacht und die Sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen, 1941-1945, Bonn: Dietz (3. Aufl., 1. Aufl. 1978), ISBN 3801250164 - "Between 22 June 1941 and the end of the war, roughly 5.7 million members of the Red Army fell into German hands. In January 1945, 930,000 were still in German camps. A million at most had been released, most of whom were so-called "volunteers" (Hilfswillige) for (often compulsory) auxiliary service in the Wehrmacht. Another 500,000, as estimated by the Army High Command, had either fled or been liberated. The remaining 3,300,000 (57.5 percent of the total) had perished."

- ^ a b Subterranea Britannica (February 2003), SiteName: Lager Sylt Concentration Camp, retrieved 2009-06-06

- ^ Matisson Consultants, Aurigny ; un camp de concentration nazi sur une île anglo-normande (English: Alderney, a Nazi concentration camp on an island Anglo-Norman), retrieved 2009-06-06 Template:Fr icon

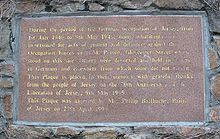

- ^ Occupation Memorial http://www.thisisjersey.com/hmd/index.html

- ^ Bunting (1995); Maughan (1980)

- ^ Jersey Heritage Trust archive*

- ^ Cruickshank (1975)

- ^ Durnford-Slater 1953, pp. 22–33.

- ^ Bunting (1995)

- ^ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/crime/article3434419.ece

- ^ Lil Dagover: Schauspielerin

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliott United States Naval Operations in World War II p.306

- ^ The Churchill Centre: The End of the War in Europe

- ^ Pether (1998), p. 7

- ^ Hansard (Commons), vol. 430, col. 138

- ^ The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, Cruickshank, London 1975 ISBN 0192850873

- ^ War Profits Levy (Jersey) Law 1945

- ^ War Profits (Guernsey) Law 1945

- ^ Occupation Diary, Leslie Sinel, Jersey 1945

- ^ The Jews in the Channel Islands During the German Occupation 1940-1945, by Frederick Cohen, President of the Jersey Jewish Congregation,http://www.jerseyheritagetrust.org/edu/resources/pdf/cijews.pdf

- ^ Noted in The Occupation, by Guy Walters, ISBN 0-7553-2066-2

- ^ Billet d'Etat Item IV, 2005

- ^ IMDb - The Blockhouse (1973)

- ^ VisitGuernsey - German Military Underground Hospital

See also

- Military history of France during World War II

- Vichy France

- Jews outside Europe under Nazi occupation

- Reichskommissariat Kaukasus

- Lokot Republic

- Fort Hommet 10.5 cm Coastal Defence Gun Casement Bunker

- Anthony Faramus

- Channel Islands

- Alderney

- Neuengamme concentration camp subcamp list

- Nazi concentration camps

- Nazi concentration camp list

- The Holocaust

References

- John Crossley Hayes teacher in charge of Vauvert school (1940 - 1945)and composer of Suite Guernesiaise, premiered in Guernsey October 2009. Documents of life in war time Guernsey at http://www.johncrossleyhayes.co.uk.

- Bunting, Madelaine (1995) The Model Occupation: the Channel Islands under German rule, 1940-1945, London : Harper Collins, ISBN 0-00-255242-6

- Edwards, G.B. (1981) "The Book of Ebenezer le Page" (New York Review of Books Classics; 2006).

- Cruickshank, Charles G. (1975) The German Occupation of the Channel Islands, The Guernsey Press, ISBN 0-902550-02-0

- Maughan, Reginald C. F. (1980) Jersey under the Jackboot, London : New English Library, ISBN 0-450-04714-8

- Pether, John (1998) The Post Office at War and Fenny Stratford Repeater Station, Bletchley Park Trust Reports, 12, Bletchley Park Trust

- Read, Brian A. (1995) No Cause for Panic - Channel Islands Refugees 1940-45, St Helier : Seaflower Books, ISBN 0-948578-69-6

- Dunford-Slater, John. (1953). Commando: Memoirs of a Fighting Commando in World War Two. Reprinted 2002 by Greenhill Books. ISBN 1-85367-479-6

- Shaffer, Mary Ann, and Barrows, Annie (2008), The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society, ISBN 978-0-385-34099-1

External links

- Occupation Memorial (Jersey resources)

- Channel Islands Occupation Society (Guernsey branch)

- Channel Islands Occupation Society (Jersey branch)

- Guernsey Society

- BBC Guernsey History - Occupation

- John Crossley Hayes Wartime Memories Guernsey

- Wartime Memories Project - The Channel Islands

- The Jersey Society In London

- The Jersey Heritage Trust Archive

- The Jews in the Occupied Channel Islands 1940-1945 {PDF}