Okinawan language

| Okinawan | |

|---|---|

| 沖縄口/ウチナーグチ Uchinaaguchi | |

| Pronunciation | [ʔut͡ɕinaːɡut͡ɕi] |

| Native to | Japan |

| Region | Okinawa Islands |

Native speakers | 980,000 (2000)[1] |

Japonic

| |

| Okinawan, Japanese, Rōmaji | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ryu |

| Glottolog | cent2126 |

| ELP | South-Central Okinawan |

| Linguasphere | 45-CAC-ai 45-CAC-aj 45-CAC-ak[2] |

(South–Central) Okinawan, AKA Shuri–Naha | |

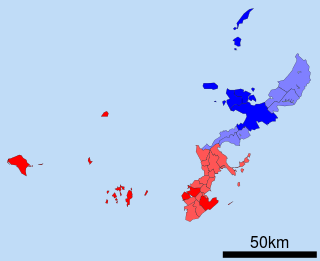

Central Okinawan, or simply the Okinawan language (沖縄口/ウチナーグチ Uchinaaguchi [ʔut͡ɕinaːɡut͡ɕi]), is a Northern Ryukyuan language spoken primarily in the southern half of the island of Okinawa, as well as in the surrounding islands of Kerama, Kumejima, Tonaki, Aguni, and a number of smaller peripheral islands.[3] Central Okinawan distinguishes itself from the speech of Northern Okinawa, which is classified independently as the Kunigami language. Both languages have been designated as endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger since its launch in February 2009.[4]

Though Okinawan encompasses a number of local dialects,[5] the Shuri-Naha variant is generally recognized as the de facto standard,[6] as it had been used as the official language of the Ryūkyū Kingdom[7] since the reign of King Shō Shin (1477–1526). Moreover, as the former capital of Shuri was built around the royal palace, the language used by the royal court became the regional and literary standard,[7][6] which thus flourished in songs and poems written during that era.

Within Japan, Okinawan is often not seen as a language unto itself but is referred to as the Okinawan dialect (沖縄方言, Okinawa hōgen) or more specifically the Central and Southern Okinawan dialects (沖縄中南部諸方言, Okinawa Chūnanbu Sho hōgen).

Okinawan speakers are undergoing language shift as they switch to Japanese. Language use in Okinawa today is far from stable. Okinawans are assimilating to standard Japanese due to the standardized education system, the expanding media, and expanding contact with mainlanders.[8] Okinawan is still spoken by many older people. It is also kept alive in theaters featuring a local drama called uchinaa shibai, which depict local customs and manners.[9]

History

- Pre-Ryukyu Kingdom

Okinawan is a Japonic language, derived from Old Japanese. The split between Old Japanese and the Ryukyuan languages has been estimated to have occurred as early as the first century AD to as late as the twelfth century AD. Chinese and Japanese characters were first introduced by a Japanese missionary in 1265.[10]

- Ryukyu Kingdom Era

- Pre-Satsuma

- Hiragana was much more popular than kanji; poems were commonly written solely in hiragana or with little kanji.

- Post-Satsuma to Annexation

- After Ryukyu became a vassal of Satsuma Domain, kanji gained more prominence in poetry, however official Ryukyuan documents were written in Classical Chinese.

- Japanese Annexation to End of World War II

When Ryukyu was annexed by Japan in 1879, the majority of people on Okinawa Island spoke Okinawan. Within ten years, the Japanese government began an assimilation policy of Japanization, where Ryukyuan languages were gradually suppressed. The education system was the heart of Japanization, where Okinawan children were taught Japanese and punished for speaking their native language, being told that their language was just a "dialect". By 1945, many Okinawans spoke Japanese, and many were bilingual. During the Battle of Okinawa, some Okinawans were killed by Japanese soldiers for speaking Okinawan.

- American Occupation

Under American administration, there was an attempt to revive and standardize Okinawan, however this proved difficult and was shelved in favor of Japanese. Multiple English words were introduced.

- Return to Japan to Present Day

After Okinawa's reversion to Japanese sovereignty, Japanese continued to be the dominant language used, and the majority of the youngest generations only speak Okinawan Japanese. There have been attempts to revive Okinawan by notable people such as Byron Fija and Seijin Noborikawa, however few native Okinawans desire to learn the language.[11]

Classification

Okinawan is sometimes grouped with Kunigami as the Okinawan languages, however some linguists don't use this grouping or claim that Kunigami is a dialect of Okinawan.[12] Okinawan is also grouped with Amami (or the Amami languages) as the Northern Ryukyuan languages.

- Dialect of the Japanese language

Since the creation of Okinawa Prefecture, Okinawan was labeled a dialect of Japanese as part of a policy of assimilation. Later, Japanese linguists, such as Tōjō Misao, who studied the Ryukyuan languages argued that they are indeed dialects. This is due to the misconception that Japan is a homogeneous state (one people, one language, one nation), and classifying the Ryukyuan languages as such would discredit this belief.[13] The present-day official stance of the Japanese government remains of the idea that Okinawan is a dialect, and it is common within the Japanese population for it to be called 沖縄方言 (okinawa hōgen) or 沖縄弁 (okinawa-ben), which means "Okinawa dialect (of Japanese)". The policy of assimilation, coupled with increased interaction between Japan and Okinawa through media and economics, has led to the development of Okinawan Japanese, which is a dialect of Japanese.

- Dialect of the Ryukyuan language

Okinawan linguist Seizen Nakasone states that the Ryukyuan languages are in fact groupings of similar dialects. As each community has its own distinct dialect, there is no "one language". Nakasone attributes this diversity to the isolation caused by immobility, citing the story of his mother who wanted to visit the town of Nago but never made the 25 km trip before she died of old age.[14]

- Its own distinct language

Outside Japan, Okinawan is considered a separate language from Japanese. This was first proposed by Basil Hall Chamberlain, who compared the relationship between Okinawan and Japanese to that of the Romance languages. UNESCO has marked it as an endangered language.

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | (ɨ) | u uː |

| Close-Mid | e eː | o oː | |

| Open | a aː |

The Okinawan language has five vowels, all of which may be long or short, though the short vowels /e/ and /o/ are considerably rare[15] as they only occur in a few native Okinawan words with heavy syllables with the pattern /Ceɴ/ or /Coɴ/, such as /meɴsoːɾeː/ mensooree "welcome" or /toɴɸaː/ tonfaa. The close back vowels /u/ and /uː/ are truly rounded, rather than the compressed vowels of standard Japanese. A sixth vowel /ɨ/ is sometimes posited in order to explain why sequences containing a historically raised /e/ fail to trigger palatalization as with /i/: */te/ → /tɨː/ tii "hand", */ti/ → /t͡ɕiː/ chii "blood". Acoustically, however, /ɨ/ is pronounced no differently from /i/, and this distinction may be because palatalization happened before this vowel shift.

Consonants

The Okinawan language counts some 20 distinctive segments shown in the chart below, with major allophones presented in parentheses.

| Labial | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Labio- velar |

Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | [[#Moraic nasal|(ŋ)]] | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | t͡ɕ d͡ʑ | kʷ ɡʷ | k ɡ | ʔ | |

| Fricative | ɸ | s (z) | (ɕ) | (ç) | h | ||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||||

| Approximant | j | w |

The only consonant that can occur as a syllable coda is the archiphoneme //n//. Many analyses treat it as an additional phoneme /N/, though it never contrasts with /n/ or /m/.

The consonant system of the Okinawan language is fairly similar to that of standard Japanese, but it does present a few differences on the phonemic and allophonic level. Namely, Okinawan retains the labialized consonants /kʷ/ and /ɡʷ/ which were lost in Late Middle Japanese, possesses a glottal stop /ʔ/, features a voiceless bilabial fricative /ɸ/ distinct from the aspirate /h/, and has two distinctive affricates which arose from a number of different sound processes. Additionally, Okinawan lacks the major allophones [t͡s] and [d͡z] found in Japanese, having historically fronted the vowel /u/ to /i/ after the alveolars /t d s z/, consequently merging [t͡su] tsu into [t͡ɕi] chi, [su] su into [ɕi] shi, and both [d͡zu] and [zu] into [d͡ʑi]. It also lacks /z/ as a distinctive phoneme, having merged it into /d͡ʑ/.

- Bilabial and glottal fricatives

- The bilabial fricative /ɸ/ has sometimes been transcribed as the cluster /hw/, since, like Japanese, /h/ allophonically labializes into [ɸ] before the high vowel /u/, and /ɸ/ does not occur before the rounded vowel /o/. This suggests that an overlap between /ɸ/ and /h/ exists, and so the contrast in front of other vowels can be denoted through labialization. However, this analysis fails to take account of the fact that Okinawan has not fully undergone the diachronic change */p/ → /ɸ/ → */h/ as in Japanese, and that the suggested clusterization and labialization into */hw/ is unmotivated.[16] Consequently, the existence of /ɸ/ must be regarded as independent of /h/, even though the two overlap. Barring a few words that resulted from the former change, the aspirate /h/ also arose from the odd lenition of /k/ and /s/, as well as words loaned from other dialects. Before the glide /j/ and the high vowel /i/, it is pronounced closer to [ç], as in Japanese.

- Palatalization

- The plosive consonants /t/ and /k/ historically palatalized and affricated into /t͡ɕ/ before and occasionally following the glide /j/ and the high vowel /i/: */kiri/ → /t͡ɕiɾi/ chiri "fog", and */k(i)jora/ → /t͡ɕuɾa/ chura- "beautiful". This change preceded vowel raising, so that instances where /i/ arose from */e/ did not trigger palatalization: */ke/ → /kiː/ kii "hair". Their voiced counterparts /d/ and /ɡ/ underwent the same effect, becoming /d͡ʑ/ under such conditions: */unaɡi/ → /ʔɴnad͡ʑi/ qnnaji "eel", and */nokoɡiri/ → /nukud͡ʑiɾi/ nukujiri "saw"; but */kaɡeɴ/ → /kaɡiɴ/ kagin "seasoning".

- Both /t/ and /d/ may or may not also allophonically affricate before the mid vowel /e/, though this pronunciation is increasingly rare. Similarly, the fricative consonant /s/ palatalizes into [ɕ] before the glide /j/ and the vowel /i/, including when /i/ historically derives from /e/: */sekai/ → [ɕikeː] shikee "world". It may also palatalize before the vowel /e/, especially so in the context of topicalization: [duɕi] dushi → [duɕeː] dusee or dushee "(topic) friend".

- In general, sequences containing the palatal consonant /j/ are relatively rare and tend to exhibit depalatalization. For example, /mj/ tends to merge with /n/ ([mjaːku] myaaku → [naːku] naaku "Miyako"); */rj/ has merged into /ɾ/ and /d/ (*/rjuː/ → /ɾuː/ ruu ~ /duː/ duu "dragon"); and /sj/ has mostly become /s/ (/sjui/ shui → /sui/ sui "Shuri").

- Flapping and fortition

- The voiced plosive /d/ and the flap /ɾ/ tend to merge, with the first becoming a flap in word-medial position, and the second sometimes becoming a plosive in word-initial position. For example, /ɾuː/ ruu "dragon" may be strengthened into /duː/ duu, and /hasidu/ hashidu "door" conversely flaps into /hasiɾu/ hashiru. The two sounds do, however, still remain distinct in a number of words and verbal constructions.

- Glottal stop

- Okinawan also features a distinctive glottal stop /ʔ/ that historically arose from a process of glottalization of word-initial vowels.[17] Hence, all vowels in Okinawan are predictably glottalized at the beginning of words (*/ame/ → /ʔami/ ami "rain"), save for a few exceptions. High vowel loss or assimilation following this process created a contrast with glottalized approximants and nasal consonants.[17] Compare */uwa/ → /ʔwa/ qwa "pig" to /wa/ wa "I", or */ine/ → /ʔɴni/ qnni "rice plant" to */mune/ → /ɴni/ nni "chest".[18]

-

- Moraic nasal

- The moraic nasal /N/ has been posited in most descriptions of Okinawan phonology. Like Japanese, /N/ (transcribed using the small capital /ɴ/) occupies a full mora and its precise place of articulation will vary depending on the following consonant. Before other labial consonants, it will be pronounced closer to a syllabic bilabial nasal [m̩], as in /ʔɴma/ [ʔm̩ma] qmma "horse". Before velar and labiovelar consonants, it will be pronounced as a syllabic velar nasal [ŋ̍], as in /biɴɡata/ [biŋ̍ɡata] bingata, a method of dying clothes. And before alveolar and alveolo-palatal consonants, it becomes a syllabic alveolar nasal /n̩/, as in /kaɴda/ [kan̩da] kanda "vine". Elsewhere, its exact realization remains unspecified, and it may vary depending on the first sound of the next word or morpheme. In isolation and at the end of utterances, it is realized as a velar nasal [ŋ̍].

Correspondences with Japanese

There is a sort of "formula" for Ryukyuanizing Japanese words: turning e into i, ki into chi, gi into ji, o into u, and -awa into -aa. This formula fits with the transliteration of Okinawa into Uchinaa and has been noted as evidence that Okinawan is a dialect of Japanese, however it does not explain unrelated words such as arigatō and nifeedeebiru (for "thank you").

| Japanese | Okinawan | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| /e/ | /iː/[19] | |

| /i/ | ||

| /a/ | /a/[19] | |

| /o/ | /u/[19] | |

| /u/ | ||

| /ai/ | /eː/ | |

| /ae/ | ||

| /au/ | /oː/ | |

| /ao/ | ||

| /aja/ | ||

| /k/ | /k/ | /ɡ/ also occurs |

| /ka/ | /ka/ | /ha/ also occurs |

| /ki/ | /t͡ɕi/ | [t͡ɕi] |

| /ku/ | /ku/ | /hu/, [ɸu] also occurs |

| /si/ | /si/ | /hi/, [çi] also occurs |

| /su/ | /si/ | [ɕi]; formerly distinguished as [si] /hi/ [çi] also occurs |

| /tu/ | /t͡ɕi/ | [t͡ɕi]; formerly distinguished as [tsi] |

| /da/ | /ra/ | [d] and [ɾ] have merged |

| /de/ | /ri/ | |

| /do/ | /ru/ | |

| /ni/ | /ni/ | Moraic /ɴ/ also occurs |

| /nu/ | /nu/ | |

| /ha/ | /ɸa/ | /pa/ also occurs, but rarely |

| /hi/ | /pi/ ~ /hi/ | |

| /he/ | ||

| /mi/ | /mi/ | Moraic /ɴ/ also occurs |

| /mu/ | /mu/ | |

| /ri/ | /i/ | /iri/ unaffected |

| /wa/ | /wa/ | Tends to become /a/ medially |

Orthography

The Okinawan language was historically written using an admixture of kanji and hiragana. The hiragana syllabary is believed to have first been introduced from mainland Japan to the Ryukyu Kingdom some time during the reign of king Shunten in the early thirteenth century.[20][21] It is likely that Okinawans were already in contact with hanzi (Chinese characters) due to extensive trade between the Ryukyu Kingdom and China, Japan and Korea. However, hiragana gained more widespread acceptance throughout the Ryukyu Islands, and most documents and letters were uniquely transcribed using this script. The Omoro Saushi (おもろさうし), a sixteenth-century compilation of songs and poetry,[22] and a few preserved writs of appointments dating from the same century were written solely in Hiragana.[23] Kanji were gradually adopted due to the growing influence of mainland Japan and to the linguistic affinity between the Okinawan and Japanese languages.[24] However, it was mainly limited to affairs of high importance and to documents sent towards the mainland. The oldest inscription of Okinawan exemplifying its use along with Hiragana can be found on a stone stele at the Tamaudun mausoleum, dating back to 1501.[25][26]

After the invasion of Okinawa by the Shimazu clan of Satsuma in 1609, Okinawan ceased to be used in official affairs.[20] It was replaced by standard Japanese writing and a form of Classical Chinese writing known as kanbun.[20] Despite this change, Okinawan still continued to prosper in local literature up until the nineteenth century. Following the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government abolished the domain system and formally annexed the Ryukyu Islands to Japan as the Okinawa Prefecture in 1879.[27] To promote national unity, the government then introduced standard education and opened Japanese-language schools based on the Tokyo dialect.[27] Students were discouraged and chastised for speaking or even writing in the local "dialect", notably through the use of "dialect cards" (方言札). As a result, Okinawan gradually ceased to be written entirely until the American takeover in 1945.

Since then, Japanese and American scholars have variously transcribed the regional language using a number of ad hoc romanization schemes or the katakana syllabary to demarcate its foreign nature with standard Japanese. Proponents of Okinawan tend to be more traditionalist and continue to write the language using hiragana with kanji. In any case, no standard or consensus concerning spelling issues has ever been formalized, so discrepancies between modern literary works are common.

- Syllabary

Technically, they are not syllables, but rather morae. Each mora in Okinawan will consist of one or two kana characters. If two, then a smaller version of kana follows the normal sized kana. In each cell of the table below, the top row is the kana (hiragana to the left, katakana to the right of the dot), the middle row in rōmaji (Hepburn romanization), and the bottom row in IPA.

| A | I | U | E | O | YA | YI | YU | YE | YO | WA | WI | WU | WE | WO | N | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ø | あ・ア a [a] |

い・イ i [i] |

う・ウ u [u] |

え・エ e [e] |

お・オ o [o] |

や・ヤ ya [ja] |

いぃ・イィ yi [ji] |

ゆ・ユ yu [ju] |

えぇ・エェ ye [je] |

よ・ヨ yo [jo] |

わ・ワ wa [wa] |

ゐ・ヰ wi [wi] |

をぅ・ヲゥ wu [wu] |

ゑ・ヱ we [we] |

を・ヲ wo [wo] |

ん・ン n [ɴ] ([n̩], [ŋ̣], [ṃ]) | ||||

| Q (glottal stop) |

あ・ア Qa [ʔa] |

い・イ Qi [ʔi] |

う・ウ Qu [ʔu] |

え・エ Qe [ʔe] |

お・オ Qo [ʔo] |

っや・ッヤ Qya [ʔʲa] |

っゆ・ッユ Qyu [ʔʲu] |

っよ・ッヨ Qyo [ʔʲo] |

っわ・ッワ Qwa [ʔʷa] |

っゐ・ッヰ Qwi [ʔʷi] |

っゑ・ッヱ Qwe [ʔʷe] |

っを・ッヲ Qwo [ʔʷo] |

っん・ッン Qn [ʔɴ] ([ʔn̩], [ʔṃ]) | |||||||

| K | か・カ ka [ka] |

き・キ ki [ki] |

く・ク ku [ku] |

け・ケ ke [ke] |

こ・コ ko [ko] |

きゃ・キャ kya [kʲa] |

きゅ・キュ kyu [kʲu] |

きょ・キョ kyo [kʲo] |

くゎ・クヮ kwa [kʷa] |

くぃ・クィ kwi [kʷi] |

くぇ・クェ kwe [kʷe] |

くぉ・クォ kwo [kʷo] | ||||||||

| G | が・ガ ga [ga] |

ぎ・ギ gi [gi] |

ぐ・グ gu [gu] |

げ・ゲ ge [ge] |

ご・ゴ go [go] |

ぎゃ・ギャ gya [gʲa] |

ぎゅ・ギュ gyu [gʲu] |

ぎょ・ギョ gyo [gʲo] |

ぐゎ・グヮ gwa [gʷa] |

ぐぃ・グィ gwi [gʷi] |

ぐぇ・グェ gwe [gʷe] |

ぐぉ・グォ gwo [gʷo] | ||||||||

| S | さ・サ sa [sa] |

すぃ・スィ si [si] |

す・ス su [su] |

せ・セ se [se] |

そ・ソ so [so] | |||||||||||||||

| SH | しゃ・シャ sha [ɕa] |

し・シ shi [ɕi] |

しゅ・シュ shu [ɕu] |

しぇ・シェ she [ɕe] |

しょ・ショ sho [ɕo] | |||||||||||||||

| Z | ざ・ザ za [za] |

ずぃ・ズィ zi [zi] |

ず・ズ zu [zu] |

ぜ・ゼ ze [ze] |

ぞ・ゾ zo [zo] | |||||||||||||||

| J | じゃ・ジャ (ぢゃ・ヂャ) ja [dʑa] |

じ・ジ (ぢ・ヂ) ji [dʑi] |

じゅ・ヂュ (ぢゅ・ヂュ) ju [dʑu] |

じぇ・ジェ (ぢぇ・ヂェ) je [dʑe] |

じょ・ジョ (ぢょ・ヂョ) jo [dʑo] | |||||||||||||||

| T | た・タ ta [ta] |

てぃ・ティ ti [ti] |

とぅ・トゥ tu [tu] |

て・テ te [te] |

と・ト to [to] | |||||||||||||||

| D | だ・ダ da [da] |

でぃ・ディ di [di] |

どぅ・ドゥ du [du] |

で・デ de [de] |

ど・ド do [do] | |||||||||||||||

| TS | つぁ・ツァ tsa [tsa] |

つぃ・ツィ tsi [tsi] |

つ・ツ tsu [tsu] |

つぇ・ツェ tse [tse] |

つぉ・ツォ tso [tso] | |||||||||||||||

| CH | ちゃ・チャ cha [tɕa] |

ち・チ chi [tɕi] |

ちゅ・チュ chu [tɕu] |

ちぇ・チェ che [tɕe] |

ちょ・チョ cho [tɕo] |

YA | YU | YO | ||||||||||||

| N | な・ナ na [na] |

に・ニ ni [ni] |

ぬ・ヌ nu [nu] |

ね・ネ ne [ne] |

の・ノ no [no] |

にゃ・ニャ nya [ɲa] |

にゅ・ニュ nyu [ɲu] |

にょ・ニョ nyo [ɲo] |

| |||||||||||

| H | は・ハ ha [ha] |

ひ・ヒ hi [çi] |

へ・ヘ he [he] |

ほ・ホ ho [ho] |

ひゃ・ヒャ hya [ça] |

ひゅ・ヒュ hyu [çu] |

ひょ・ヒョ hyo [ço] | |||||||||||||

| F | ふぁ・ファ fa [ɸa] |

ふぃ・フィ fi [ɸi] |

ふ・フ fu/hu [ɸu] |

ふぇ・フェ fe [ɸe] |

ふぉ・フォ fo [ɸo] |

|||||||||||||||

| B | ば・バ ba [ba] |

び・ビ bi [bi] |

ぶ・ブ bu [bu] |

べ・ベ be [be] |

ぼ・ボ bo [bo] |

|||||||||||||||

| P | ぱ・パ pa [pa] |

ぴ・ピ pi [pi] |

ぷ・プ pu [pu] |

ぺ・ペ pe [pe] |

ぽ・ポ po [po] |

|||||||||||||||

| M | ま・マ ma [ma] |

み・ミ mi [mi] |

む・ム mu [mu] |

め・メ me [me] |

も・モ mo [mo] |

みゃ・ミャ mya [mʲa] |

みゅ・ミュ myu [mʲu] |

みょ・ミョ myo [mʲo] | ||||||||||||

| R | ら・ラ ra [ɾa] |

り・リ ri [ɾi] |

る・ル ru [ɾu] |

れ・レ re [ɾe] |

ろ・ロ ro [ɾo] |

りゃ・リャ rya [ɾʲa] |

りゅ・リュ ryu [ɾʲu] |

りょ・リョ ryo [ɾʲo] | ||||||||||||

Grammar

Okinawan follows a subject>object>verb word order and makes large use of particles as in Japanese. Okinawan dialects retain a number of grammatical features of classical Japanese, such as a distinction between the terminal form (終止形) and the attributive form (連体形), the genitive function of が ga (lost in the Shuri dialect), the nominative function of ぬ nu (Japanese: の no), as well as honorific/plain distribution of ga and nu in nominative use.

| 書く kaku to write | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical | Shuri | |||

| Irrealis | 未然形 | 書か | kaka- | kaka- |

| Continuative | 連用形 | 書き | kaki- | kachi- |

| Terminal | 終止形 | 書く | kaku | kachun |

| Attributive | 連体形 | 書く | kaku | kachuru |

| Realis | 已然形 | 書け | kake- | kaki- |

| Imperative | 命令形 | 書け | kake | kaki |

One etymology given for the -un and -uru endings is the continuative form suffixed with uri (Classical Japanese: 居り wori, to be; to exist): -un developed from the terminal form uri; -uru developed from the attributive form uru, i.e.:

- kachuru derives from kachi-uru;

- kachun derives from kachi-uri; and

- yumun (Japanese: 読む yomu, to read) derives from yumi + uri.

A similar etymology is given for the terminal -san and attributive -saru endings for adjectives: the stem suffixed with さ sa (nominalises adjectives, i.e. high → height, hot → heat), suffixed with ari (Classical Japanese: 有り ari, to exist; to have), i.e.:

- takasan (Japanese: 高い takai, high; tall) derives from taka-sa-ari;

- achisan (Japanese: 暑い atsui, hot; warm) derives from atsu-sa-ari; and

- yutasaru (good; pleasant) derives from yuta-sa-aru.

Parts of Speech

| Nature of the Part of Speech in a Sentence | Part of Speech | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | No Conjugation | Can become a subject | Noun (名詞) | ||||

| Pronoun (代名詞) | |||||||

| Cannot become a subject | Other words come after | Modifies | Modifies a declinable word | Adverb (副詞) | |||

| Modifies a substantive | Prenominal Adjective (連体詞) | ||||||

| Connects | Conjunction (接続詞) | ||||||

| Other words may not come after | Interjection / Exclamation (感動詞) | ||||||

| Conjugates | Declinable word | Shows movements | Conclusive form ends in "ん (n)" | Verb (動詞) | |||

| Shows the property or state | Conclusive form ends in "さん (san)" | Adjective (形容詞) | |||||

| Shows existence or decision of a certain thing | "やん (yan)" attaches to a substantive such as a noun | ??? (存在動詞) | |||||

| Shows state of existence of events | "やん (yan)" attaches to the word that shows state | Adjectival Verb (形容動詞) | |||||

| Dependent | Conjugates | Makes up for the meanings of conjugated words | Conclusive form ends in "ん (n)" | Auxiliary Verb (助動詞) | |||

| No Conjugation | Attaches to other words and shows the relationship between words | Particle(助詞) | |||||

| Attaches to the head of a word and adds meaning or makes a new word | Prefix (接頭語) | ||||||

| Attaches to the end of a word and adds meaning or makes a new word | Suffix (接尾語) | ||||||

- Nouns (名詞)

Nouns are classified as independent, non-conjugating part of speech that can become a subject of a sentence

- Pronouns (代名詞)

Pronouns are classified the same as nouns, except that pronouns are more broad.

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal | Demonstrative | Personal | Demonstrative | ||||||

| Thing | Place | Direction | Thing | Place | Direction | ||||

| 1st Person |

|

|

|||||||

| 2nd Person |

|

|

|||||||

| 3rd Person | Proximal | くり (kuri) | くり (kuri) | くま (kuma) |

|

くったー (kuttaa) | くったー (kuttaa) | くま (kuma) |

|

| Medial | うり (uri) | うり (uri) | うま (uma) |

|

うったー (uttaa) | うったー (uttaa) | うま (uma) |

| |

| Distal | あり (ari) | あり (ari) | あま (ama) |

|

あったー (attaa) | あったー (attaa) | あま (ama) |

| |

| Indefinite |

|

じる (jiru) | まー (maa) |

|

たったー (tattaa) | じる (jiru) | まー (maa) |

| |

- Adverbs (副詞)

Adverbs are classified as an independent, non-conjugating part of speech that cannot become a subject of a sentence and modifies a declinable word (用言; verbs, adverbs, adjectives) that comes after the adverb. There are two main categories to adverbs and several subcategories within each category, as shown in the table below.

| Adverbs that shows state or condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shows... | Okinawan | Japanese | English | Example |

| Time | ひっちー (hicchii) | しょっちゅう (shocchuu) いつも (itsumo) 始終 (shijyuu) |

Always |

anu fitundaa hicchii, takkwaimukkwai bikeesoon.

ano fuufu ha itsumo, yorisotte bakari iru.

|

| まーるけえてぃ (maarukeeti) | たまに (tamani) | Occasionally |

kwam maarukeeti, uyanu kashiishiga ichun

kodomo ha tamani, oyano tetsudai ni iku.

| |

| ちゃーき (chaaki) | 直ぐ (sugu) | Already |

Kono kuruma ha sugu, kowarete shimatteita.

| |

| やがてぃ (yagati) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | Shortly |

Yagati, tida nu utiyushiga, unjyuoo kuun.

Yagate, taiyou ga ochiruga, anatawa konai.

| |

| 未だ (naada) | まだ (mada) | Yet |

Ariga chimuoo naada, nooran.

kanojyo no kigenwa mada, naoranai.

| |

| ちゃー (chaa) | いつも (itsumo) | Always |

| |

| ちゅてーや (chuteeya) | 少しは (sukoshiwa) | A little |

| |

| あっとぅむす (attumusu) | 急に (kyuuni) |

| ||

| まるひーじーや (maruhiijiiya) | 普段は (fudanwa) | Normally |

| |

| いっとぅちゃー (ittuchaa) | しばらくは (shibarakuwa) |

| ||

| Quantity | いふぃ (ifi) | 少し (sukoshi) |

| |

| ちゃっさきー (chassakii) | 沢山 (takusan) |

| ||

| はてぃるか (hatiruka) | 随分 (zuibun) |

| ||

| ぐゎさない (gwasanai) | わんさか (wansaka) |

| ||

| 満っちゃきー (micchakii) 満っちゃかー (micchakaa) |

一杯 (ippai) | A lot |

| |

| ゆっかりうっさ (yukkariussa) | 随分 (zuibun) |

| ||

| うすまさ (usumasa) | 恐ろしく (osoroshiku) |

| ||

| まんたきー (mantakii) | 一杯 (ippai) |

| ||

| なーふぃん (naafin) | もっと (motto) |

| ||

| 軽ってんぐゎ (kattengwa) | 少しだけ (sukoshidake) |

| ||

| Degree | でーじな (deejina) | 大変 (taihen) |

| |

| じまま (jimama) | 随分 (zuibun) |

| ||

| よねー (yonee) | そんなには (son'naniwa) |

| ||

| いーるく (iiruku) | 良く (yoku) |

| ||

| にりるか (niriruka) | うんざりするほど (unzarisuruhodo) |

| ||

| わじるか (wajiruka) | 怒るほど (okoruhodo) |

| ||

| あいゆか (aiyuka) | とても (totemo) |

| ||

| ゆくん (yukun) | 余計 (yokei) |

| ||

| たった (tatta) | 余計 (yokei) |

| ||

| ちゅふぁーら (chufaara) | 一杯 (ippai) |

| ||

| あんすかー (ansukaa) | それほどは (sorehodowa) |

| ||

| 散ん散んとぅ (chinchintu) | 散り散りに (chirichirini) |

| ||

| Situation | 早く (heeku) | 早く (hayaku) |

| |

| ようんなー (youn'naa) | ゆっくり (yukkuri) |

| ||

| なんくる (nankuru) | 自ずと (onozuto) |

| ||

| ゆったいくゎたい (yuttaikwatai) | どんぶらこと (donburakoto) |

| ||

| なぐりなぐりとぅ (nagurinaguritu) | なごりなごりと (nagorinagorito) |

| ||

| しんじんとぅ (shinjintu) | しみじみと (shimijimito) |

| ||

| 次第次第 (shideeshidee) | 次第次第 (shidaishidai) |

| ||

| ちゅらーさ (churaasa) | 残らず (nokorazu) |

| ||

| どぅく (duku) | あまりにも (amarinimo) |

| ||

| だんだんだんだん (dandandandan) | 段々 (dandan) |

| ||

| 次第に (shideeni) | 次第に (shidaini) |

| ||

| どぅくだら (dukudara) | ひどく (hidoku) |

| ||

| まっすぐ (massugu) | まっすぐ (massugu) |

| ||

| まっとうば (mattouba) | 正しく (tadashiku) |

| ||

| だってぃどぅ (dattidu) | ちゃんと (channto) |

| ||

| だてん (daten) | きちんと (kichinto) |

| ||

| さっぱっとぅ (sappattu) | さっぱり (sappari) |

| ||

| しかっとぅ (shikattu) | しっかり (shikkari) |

| ||

| うかっとぅお (ukattuo) | うかつには (ukatsuniwa) |

| ||

| たった (tatta) | 余計 (yokei) |

| ||

| Adverbs that shows judgement | ||||

| Shows... | Okinawan | Japanese | English | Example |

| Assumption | むし (mushi) | もし (moshi) | If |

|

| たとぅい (tatui) | 例え (tatoe) | Even if |

| |

| 例れー (taturee) | 例えば (tatoeba) |

| ||

| Supposition | いやりん (iyarin) | きっと(いかにも) (kitto (ikanimo)) |

| |

| まさか (masaka) | まさか (masaka) |

| ||

| むしや (mushiya) | もしや (moshiya) |

| ||

| むしか (mushika) | もしや (moshiya) |

| ||

| まさか (masaka) | まさか (masaka) |

| ||

| あたまに (atamani) | ほんとに (hontoni) |

| ||

| Wish | どうでぃん (doudin) | どうか (douka) |

| |

| たんでぃ (tandi) | どうぞ (douzo) |

| ||

| 必じ (kan'naji) | 必ず (kanarazu) |

| ||

| 如何しん (chaashin) | どうしても (doushitemo) |

| ||

| Doubt | 如何し (chaashi) | どうやって (douyatte) |

| |

| みったい (mittai) | 一体 (ittai) |

| ||

| あんすか (ansuka) | そんなに (son'nani) |

| ||

| 何んち (nuunchi) | 何故 (naze) |

| ||

| Denial or Negation |

あちらん (achiran) | 一向に (ikkouni) |

| |

| じょうい (jyoui) | 絶対 (zettai) | Definitely |

| |

| ちゃっさん (chassan) | 度を超して (dowokoshite) |

| ||

| いふぃん (ifin) | 少しも (sukoshimo) |

| ||

| 如何ん (chaan) | どうすることも (dousurukotomo) |

| ||

| Decision | じゅんに (jyun'ni) | 本当に (hontouni) |

| |

| 必じ (kan'naji) | 必ず (kanarazu) |

| ||

| うん如おりー (ungutuorii) | そのような事 (sonoyounakoto) |

| ||

| Others | いちゃんだん (ichandan) | むやみに (muyamini) |

| |

| うったてぃ (uttati) | わざと (wazato) |

| ||

| なー (naa) | もう (mou) |

| ||

- Prenominal Adjectives (連体詞)

| Prenominal Adjectives are classified the same as adverbs, except instead of modifying a declinable word, it modifies a substantive (体言; nouns and pronouns). | ||

| Okinawan | Japanese | English |

|---|---|---|

| いぃー (yii) | 良い (ii) | |

- Conjunctions (接続詞)

| Conjunctions are classified as an independent, non-conjugating part of speech that connects words coming after to words coming before. | ||

| Okinawan | Japanese | English |

|---|---|---|

| あんさびーくとぅ (ansabiikutu) | そういうわけですから (souiuwakedesukara) | "For that reason" |

| あんし (anshi) | それで (sorede) それから (sorekara) |

"And then" |

| やくとぅ (yakutu) | だから (dakara) | "So" |

| やしが (yashiga) | しかし (shikashi) そうではあるが (soudewa'aruga) |

"But" |

- Interjections / Exclamations (感動詞)

| Interjections are classified as an independent, non-conjugating part of speech, where it does not modify or connect anything, and other words may not come after it. | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | English | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| あい (ai) | おや (oya) | 驚きの気持ちを表す | |

| あきさみよー (akisamiyo) | あらまあ (aramaa) | ||

| あきとーなー (akitoonaa) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 失敗した時や驚いた時などに発する | |

| うー (uu) | はい (hai) | ||

| あいびらん (aibiran) をぅーをぅー (wuuwuu) |

いいえ (iie) | 目上の人に対して用いる | |

| だー (daa) | おい (oi) どれ (dore) ほら (hora) |

||

| とー (too) | ほら (hora) よし (yoshi) |

||

| とーとー (tootoo) | よしよし (yoshiyoshi) ほらほら (horahora) |

||

| はっさみよー (hassamiyoo) | おやまあ (oyamaa) | 呆れ返った時などに発する語 | |

| んちゃ (ncha) | なるほど (naruhodo) やっぱり (yappari) 予定通りだ (yoteidourida) |

||

- Verbs (動詞)

Verbs are classified as an independent, conjugating part of speech that shows movements. The conclusive form ends in ん (n).

- Adjectives (形容詞)

Adjectives are classified as an independent, conjugating part of speech that shows property or state. The conclusive form ends in さん (san).

- (存在動詞)

存在動詞 are classified as an independent, conjugating part of speech that shows existence or decision of a certain thing. やん (yan) attaches to a substantive.

- Adjectival Verbs (形容動詞)

Adjectival verbs are classified as an independent, conjugating part of speech that shows the state of existence of events. やん (yan) attaches to words that shows state.

- Auxiliary Verbs (助動詞)

| Auxiliary verbs are classified as a dependent, conjugating part of speech that makes up the meanings of conjugated words. The conclusive form ends in ん (n). | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | English | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| あぎーん (agiin) あぎゆん (agiyun) |

しつつある (shitsutsuaru) | ||

| ぎさん (gisan) | そうだ (souda) | ||

| ぐとーん (gutoon) | のようだ (noyouda) | ||

| しみゆん (shimiyun) すん (sun) |

させる (saseru) | ||

| ぶさん (busan) | したい (shitai) | ||

| みしぇーびーん (misheebiin) | なさいます (nasaimasu) | ||

| みしぇーん (misheen) | なさる (nasaru) | ||

| ゆーすん (yuusun) | ことができる (kotogadekiru) | ||

| りゆん (riyun) りーん (riin) |

れる (reru) られる (rareru) |

||

| Case Markers (格助詞) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Attaches to a substantive and marks the relationship between other words. | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| ぬ (nu) が (ga) |

が (ga) | Subject marker. Normally ぬ (nu). However, if a pronoun is the subject of the sentence, が (ga) is used. が (ga) can also be used for names. ぬ (nu) can be used for any situation. |

|

| っし (sshi) | で (de) | Indicates the means by which something is achieved. |

|

| Ø (Archaic: ゆ (yu)) | を (wo) | Modern Okinawan does not use an direct object particle, like casual Japanese speech . "yu" exists mainly in old literary composition. |

|

| なかい (nakai) | へ (e)・{{nihongo3|に|ni} | 手段・方法 |

|

| やか (yaka) | より (yori) | "as much as"; upper limit. |

|

| さあに (saani) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | Indicates the means by which something is achieved. |

|

| から (kara) | から (kara) | 起点 |

|

| んかい (nkai) | へ (e) | "to, in"; direction |

|

| なありい (naarii) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 場所・位置 |

|

| をぅてぃ (wuti) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | Indicates the location where an action pertaining to an animate subject takes place. Derives from the participle form of the verb をぅん wun "to be, to exist". |

|

| をぅとおてぃ (wutooti) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | Progressive form of をぅてぃ, and also includes time. |

|

| んじ (nji) | で (de) | 場所 |

|

| ん (n) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 所属等 |

|

| ぬ (nu) | の (no) | Possessive marker. It may be difficult to differentiate between the subject marker ぬ (nu) and possessive marker ぬ (nu). |

|

| ぬ→「〜している」「〜である」「〜い・しい」pp459. |

| ||

| とぅ (tu) | と (to) | 相手 |

|

| んでぃ (ndi) | と (to) | Quotative. |

|

| に (ni) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 時・場所等 |

|

| Adverbial Particles (副助詞) | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| びけえ (bikee) | だけ (dake) |

| |

| びけーん (bikeen) | ぱかり (bakari) | "only; limit" |

|

| だき (daki) | だけ (dake) |

| |

| までぃ (madi) | まで (made) | "up to, until, as far as" |

|

| くれえ (kuree) | ぐらい (gurai) | "around, about, approximately" |

|

| ふどぅ (fudu) | ほど (hodo) |

| |

| あたい (atai) | ぐらい (gurai)等 | as much as; upper limit. |

|

| んちょうん (nchoun) | さえ (sae) |

| |

| うっさ (ussa) | だけ (dake)等 |

| |

| うっぴ (uppi) | だけ (dake)等 |

| |

| うひ (uhi) | だけ (dake)等 |

| |

| さく (saku) | ほど (hodo)、だけ (dake) |

| |

| Binding Particles (係助詞) | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| や (ya) | は (wa) | Topic particle for long vowels, proper nouns, or names.

For other nouns, the particle fuses with short vowels. a → aa, i → ee, u → oo, e → ee, o → oo, n → noo. Pronoun 我ん (wan?) (I) becomes topicalized as 我んねー (wan'nee?) instead of 我んのー (wan'noo?) or 我んや (wan'ya?), although the latter does appear in some musical or literary works. |

|

| あ (a) |

| ||

| え (e) |

| ||

| お (o) |

| ||

| のお (noo) |

| ||

| ん (n) | も (mo) | "Also" |

|

| やてぃん (yatin) | でも (demo) | "even, also in" |

|

| がん (gan) | でも (demo) |

| |

| ぬん (demo) | でも (demo) |

| |

| しか (shika) | しか (shika) |

| |

| てぃらむん (tiramun) | たるもの (tarumono) |

| |

| とぅか (tuka) | とか (toka) や (ya) |

| |

| どぅ (du) | ぞ (zo) こそ (koso) |

| |

| る (ru) | ぞ (zo) こそ (koso) |

| |

| Sentence Ending Particles (終助詞) | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| が (ga)

やが (yaga) |

か (ka) | Final interrogatory particle. |

|

| み (mi) | か (ka) | Final interrogatory particle |

|

| に (ni) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 可否疑問 |

|

| い (i) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 強調疑問 |

|

| がやあ (gayaa) | かな (kana) |

| |

| さに (sani) | だろう (darou) |

| |

| なあ (naa) | の (no) | Final particle expressing 問いかけ・念押し |

|

| ばあ (baa) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 軽い疑問 |

|

| どお (doo) | ぞ (zo) よ (yo) |

| |

| よ (yo) | よ (yo) |

| |

| ふう (fuu) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 軽く言う |

|

| な (na) | な (na) | Prohibitive |

|

| え (e) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 命令 |

|

| さ (sa) | さ (sa) |

| |

| でむね (demune) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 断定 |

|

| せえ (see) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 断定 |

|

| Interjectory Particles (間投助詞) | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| てえ (tee) | ね (ne)等 |

| |

| よ (yo) よお (yoo) |

ね (ne) よ (yo)等 |

| |

| や (ya) やあ (yaa) |

ぬ (nu) よ (yo)等 |

| |

| なあ (naa) | ね (ne)等 |

| |

| さり (sari) | ねえ (nee)等 |

| |

| ひゃあ (hyaa) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | 意外、軽蔑 |

|

| Conjunctive Particles (接続助詞) | |||

| Okinawan | Japanese | Notes/English | Example |

| error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | error: {{nihongo}}: Japanese or romaji text required (help) | a |

|

- Prefix (接頭語)

- Suffix (接尾語)

Others

Copula

| Okinawan | Past Tense | Japanese |

|---|---|---|

| あびーん (abiin) いびーん (ibiin) |

A | ます (masu) |

です (desu) | ||

| やいびーん (yaibiin) | ||

でーびる (deebiru) |

A | |

| でございます (degozaimasu) |

Question Words (疑問詞)

| Okinawan | Japanese | English |

|---|---|---|

| いくち (ikuchi) | いくつ (ikutsu) | "How much" |

| いち (ichi) | いつ (itsu) | "When" |

| じる (jiru) | どれ (dore) | "Which" |

| たー (taa) | 誰 (dare) | "Who" |

| たったー (tattaa) | 誰々 (daredare) | "Who" (plural) |

| ちゃー (chaa) | どう (dou) | "How" (in what way) |

| ちぁっさ (chassa) | どれだけ (doredake) いくら (ikura) |

"How much" |

| ちゃっぴ (chappi) ちゃぬあたい (chanuatai) |

どれほど (dorehodo) | "How" |

| ちゃぬ (chanu) | どの (dono) どのような (donoyouna) |

"What kind" |

| ぬー (nuu) | 何 (nani) | "What" |

| ぬーんち (nuunchi) | どうして (doushite) | "Why" |

| まー (maa) | どこ (doko) | "Where" |

Notes

- ^ Okinawan at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Mimizun.com 2005, Comment #658 – 45-CAC-ai comprises most of Central Okinawa, including Shuri (Naha), Ginowan and Nishihara; 45-CAC-aj comprises the southern tip of Okinawa Island, including Itoman, Mabuni and Takamine; 45-CAC-ak encompasses the region west of Okinawa Island, including the Kerama Islands, Kumejima and Aguni.

- ^ Lewis 2009.

- ^ Moseley 2010.

- ^ Kerr 2000, p. xvii.

- ^ a b Brown & Ogilvie 2008, p. 908.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2008, p. 130.

- ^ Noguchi 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Noguchi 2001, p. 76.

- ^ Hung, Eva and Judy Wakabayashi. Asian Translation Traditions. 2014. Routledge. Pg 18.

- ^ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2012/05/19/national/okinawans-push-to-preserve-unique-language/#.VNrermK9KK0

- ^ Heinrich, Patrick et al. Handbook of the Ryukyuan Languages. 2015. Pp 14–15.

- ^ Heinrich, Patrick. The Making of Monolingual Japan. 2012. Pp 85–87.

- ^ Nakasone, Seizen. Festschrift. 1962. Pp. 619.

- ^ Noguchi & Fotos 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Miyara 2009, p. 179.

- ^ a b Curry 2004, §2.2.2.1.9.

- ^ Miyara 2009, p. 186.

- ^ a b c Noguchi 2001, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Kodansha 1983, p. 355.

- ^ OPG 2003.

- ^ Kerr 2000, p. 35.

- ^ Takara & 1994-1995, p. 2.

- ^ WPL 1977, p. 30.

- ^ Ishikawa 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Okinawa Style 2005, p. 138.

- ^ a b Tanji 2006, p. 26.

References

- Template:Ja icon "民族、言語、人種、文化、区別スレ". Mimizun.com. 2005-08-31. Retrieved 2010-12-26.[unreliable source?]

- Moseley, Christopher (2010). "Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger" (3rd ed.). UNESCO Publishing. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kerr, George H. (2000). Okinawa, the history of an island people. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-2087-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (2008). Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-087774-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaplan, Robert B. (2008). Language Planning and Policy in Asia: Japan, Nepal, Taiwan and Chinese characters. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-84769-095-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Noguchi, Mary Goebel; Fotos, Sandra (2001). Proto-Japanese: issues and prospects. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 1-85359-490-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miyara, Shinsho (2009). "Two Types of Nasal in Okinawa" (PDF). 言語研究(Gengo Kenkyu). University of the Ryukyus. Retrieved 2010-12-25.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curry, Stewart A. (2004). Small Linguistics: Phonological history and lexical loans in Nakijin dialect Okinawan. Ph.D. - East Asian Languages and Literatures (Japanese), University of Hawaii at Manoa.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Takara, Kurayoshi (1994–1995). "King and Priestess: Spiritual and Political Power in Ancient Ryukyu" (PDF). The Ryukyuanist (27). Shinichi Kyan. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ishikawa, Takeo (April 2002). 新しいまちづくり豊見城市 (PDF). しまてぃ (in Japanese) (21). 建設情報誌. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Template:Ja icon "Worldwide Heritages in Okinawa: Tamaudun". 沖縄スタイル (07). 枻出版社. 2005-07-10. ISBN 4-7779-0333-8. Retrieved 2011-03-14.[unreliable source?]

- Kodansha – encyclopedia of Japan. Vol. 6. Kodansha. 1983. ISBN 0-87011-626-6.

- Working papers in linguistics. Vol. 9. Dept. of Linguistics, University of Hawaii. 1977.[unreliable source?]

- "King Shunten 1187-1237". Okinawa Prefectural Government. 2003. Retrieved 2011-03-14.

- Tanji, Miyume (2006). Myth, protest and struggle in Okinawa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-36500-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Noguchi, M.G. (2001). Studies in Japanese Bilungualism. Multilingual Matters Ltd. ISBN 978-1853594892.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davis, Christopher (2013). "The Role of Focus Particles in Wh-Interrogatives: Evidence from a Southern Ryukyuan Language" (PDF). University of the Ryukyus. Retrieved 2014-04-19.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- 首里・那覇方言概説(首里・那覇方言音声データベース)

- うちなあぐち by Kiyoshi Fiza, an Okinawan language writer.