Pachamama

| Pachamama | |

|---|---|

Earth, life, harvest, farming, crops, fertility | |

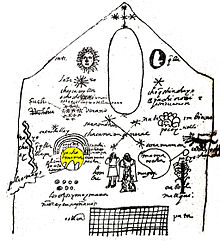

Representation of Pachamama in the cosmology, according to Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamayhua (1613), after a picture in the Sun Temple Qurikancha in Cusco | |

| Other names | Mama Pacha, Mother Earth, Queen Pachamama |

| Region | Andes Mountains (Inca Empire) |

| Consort | Pacha Kamaq |

| Offspring | Inti Mama Killa |

Pachamama is a goddess revered by the indigenous people of the Andes. She is also known as the earth/time mother.[1] In Inca mythology, Pachamama is a fertility goddess who presides over planting and harvesting, embodies the mountains, and causes earthquakes. She is also an ever-present and independent deity who has her own self-sufficient and creative power to sustain life on this earth.[1] Her shrines are hallowed rocks, or the boles of legendary trees, and her artists envision her as an adult female bearing harvests of potatoes and coca leaves. Pachamama is the wife of Pacha Kamaq and her children are Inti, the sun god, and Killa, the moon goddess.[2] The four cosmological Quechua principles - Water, Earth, Sun, and Moon[2] - claim Pachamama as their primordial origin, and priests sacrifice llamas, cuy (guinea pigs), and elaborate, miniature, burned garments to her.[3] After the conquest by Spain, which forced conversion to Roman Catholicism, the figure of the Virgin Mary became united with that of the Pachamama for many of the indigenous people.[4] In pre-Hispanic culture, Pachamama is often a cruel goddess eager to collect her sacrifices. As Andes cultures form modern nations, Pachamama remains benevolent, giving,[5] and a local name for Mother Nature. Thus, many in South America believe that problems arise when people take too much from nature because they are taking too much from Pachamama.[6]

Etymology

Pachamama is usually translated as Mother Earth, but a more literal translation would be "World Mother" (in Aymara and Quechua. Since there is no equal diction in modern Spanish or English, it was translated by the first Spaniard Chronists[7] as mama = mother / pacha = world or land; and later widened in a modern meaning as the cosmos or the universe).[8] The Inca goddess can be referred to in multiple ways; the primary way being Pachamama. Other names for her are: Mama Pacha, La Pachamama, and Mother Earth. La Pachamama differs from Pachamama because the "La" signifies the interwoven connection that the goddess has with nature, whereas Pachamama—without the "La"—refers to only the goddess.

Modern-day rituals

Pachamama and Inti are believed to be the most benevolent deities; they are worshiped in parts of the Andean mountain ranges, also known as Tawantinsuyu (the former Inca Empire) (stretching from present day Bolivia, Ecuador, Chile, Peru, and northern Argentina. Pachamama is known to Andean people as a "good mother". Therefore, people usually toast to her honor before every meeting or festivity, in some regions by spilling a small amount of chicha on the floor, before drinking the rest. This toast is called challa and it is made almost every day. Pachamama has a special worship day called Martes de challa (Challa's Tuesday), when people bury food, throw candies, and burn incense. In some cases, celebrants assist traditional priests, known as yatiris in Aymara, in performing ancient rites to bring good luck or the good will of the goddess, such as sacrificing guinea pigs or burning llama fetuses (although this is rare today). The festival coincides with Shrove Tuesday, also celebrated as Carnevale or Mardi Gras. The central ritual to Pachamama is the Challa or Pago (Payment). It is carried out during all of August, and in many places also on the first Friday of each month. Other ceremonies are carried out in special times, as upon leaving for a trip or upon passing an apacheta. According to Mario Rabey and Rodolfo Merlino, Argentine anthropologists who studied the Andean culture from the 1970s to the 1990s, "The most important ritual is the challaco. Challaco is a deformation of the Quechua words 'ch'allay' and 'ch'allakuy', that refer to the action to insistently sprinkle.[8] In the current language of the campesinos of the southern Central Andes, the word challar is used in the sense of "to feed and to give drink to the land'. The challaco covers a complex series of ritual steps that begin in the family dwellings the night before. They cook a special food, the tijtincha. The ceremony culminates at a pond or stream, where the people offer a series of tributes to Pachamama, including "food, beverage, leaves of coca and cigars.[9][10]

Household rituals

Rituals to honor Pachamama take place all year, but are especially abundant in August, right before the sowing season.[2] Because August is the coldest month of the winter in the southern Andes, people feel more vulnerable to illness.[2] August is therefore regarded as a “tricky month.”[2] During this time of mischief, Andeans believe that they must be on very good terms with nature to keep themselves and their crops and livestock healthy and protected.[2] In order to do this, families perform cleansing rituals by burning plants, wood and other items in order to scare evil spirits who are thought to be more abundant at this time.[2] People also drink mate (a South American hot beverage), which is thought to give good luck.[2]

On the night before August 1, families prepare to honor Pachamama by cooking all night.[2] The host of the gathering then makes a hole in the ground[2] If the soil comes out nicely, this means that it will be a good year; if not, the year will not bountiful.[2] Before any of the guests are allowed to eat, the host must first give a plate of food to Pachamama.[2] Food that was left aside is poured onto the ground and a prayer to Pachamama is recited.[2]

Sunday parade

A main attraction of the Pachamama festival is the Sunday parade. The organizational committee of the festival searches for the oldest woman in the community and elects her the “Pachamama Queen of the Year.”[2] This election first occurred in 1949. Indigenous women, in particular senior women, are seen as incarnations of tradition and as living symbols of wisdom, life, fertility, and reproduction. The Pachamama queen who is elected is escorted by the Gauchos who circle the plaza on their horses and salute her during the Sunday parade. The Sunday parade is considered to be the climax of the festival.[2]

New Age worship

There has been a recent rise in a New Age practice among white and Andean mestizo peoples. There is a weekly ritual worship which takes place on Sundays and includes invocations to Pachamama in Quechua, although there are some references in Spanish.[11] Inside the temple, there is a large stone with a medallion on it, symbolizing the New Age group and its beliefs. A bowl of dirt on the right of the stone is there to represent Pachamama, because of her status as a Mother Earth.[11] Many rituals related to the Pachamama are practiced in conjunction with those of Christianity, to the point that many families are simultaneously Christian and pachamamistas.[10] Pachamama is sometimes syncretized as the Virgin of Candelaria.[12] Certain travel agencies have drawn upon the emerging New Age movement in Andean communities (drawn from Quechua Indian ritual practices) to urge tourists to come to visit Inca sites. Tourists visiting these sites, such as Machu Picchu and Cusco, are offered the chance to participate in ritual offerings to Pachamama.[6] The tourist market has been using Pachamama to increase its draw to tourists.

Political usage

Belief in Pachamama features proprominently in the Peruvian national narrative. Former President, Alejandro Toledo, held a symbolic inauguration on 28 July 2001 atop Machu Picchu which featured a Quechua religious elder giving an offering to Pachamama.[6] Pachamama has also been used as an example of autochthony by some Andean intellectuals.

See also

- Gaia (mythology)

- Goddess movement

- Mother Nature

- Mother goddess

- Atabey (goddess)

- Law of the Rights of Mother Earth

- Pachamama Raymi

- Willka Raymi

- Pachamama Alliance

Notes

- ^ a b Dransart, Penny. (1992) "Pachamama: The Inka Earth Mother of the Long Sweeping Garment." Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning. Ed. Ruth Barnes and Joanne B. Eicher. New York/Oxford: Berg. 145-63. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Matthews-Salazar, Patricia. (2006) "Becoming All Indian: Gauchos, Pachamama Queens, and Tourists in the Remaking of an Andean Festival." Festivals, Toursism and Social Change: Remaking Worlds. Ed. David Picard and Mike Robinson. N.p.: Channel View Publications. 71-81. Print.

- ^ Murra, John V. (1962). "Cloth and Its Functions in the Inca State". American Anthropologist. 64 (4): 714. doi:10.1525/aa.1962.64.4.02a00020.

- ^ Merlino, Rodolfo y Mario Rabey (1992). "Resistencia y hegemonía: Cultos locales y religión centralizada en los Andes del Sur". Allpanchis (in Spanish) (40): 173–200.

- ^ Molinie, Antoinette (2004). "The Resurrection of the Inca: The Role of Indian Representations in the Invention of the Peruvian Nation". History and Anthropology. 15 (3): 233–250. doi:10.1080/0275720042000257467.

- ^ a b c Hill, Michael (2008). "Inca of the Blood, Inca of the Soul". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 76 (2): 251–279. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfn007.

- ^ Crónicas del Descubrimiento y de la Conquista: Cronistas que refieren de cultos telúricos: Pedro Sancho de la Hoz (1534); Miguel de Estete (1534); Pedro Pizarro (1571)

- ^ a b Lira, Jorge A (1944). Diccionario Kkechuwa - Español (in Spanish). Tucumán, Argentina.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mario Rabey y Rodolfo Merlino (1988). Jorge Flores Ochoa (ed.). "El control ritual-rebaño entre los pastores del altiplano argentino". Llamichos y paqocheros: Pastores de llamas y alpacas (in Spanish). Cusco, Perú: 113–120.

- ^ a b Merlino, Rodolfo y Mario Rabey (1983). "Pastores del Altiplano Andino Meridional: Religiosidad, Territorio y Equilibrio Ecológico". Allpanchis (in Spanish) (21). Cusco, Perú: 149–171.

- ^ a b Hill, Michael D. (2010). "Myth, Globalization, and Mestizaje in New Age Andean Religion". Ethnohistory. 57 (2): 263–289. doi:10.1215/00141801-2009-063.

- ^ Manuel Paredes Izaguirre. "COSMOVISION Y RELIGIOSIDAD EN LA FESTIVIDAD" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2010-02-15.

References

Dransart, Penny. (1992) "Pachamama: The Inka Earth Mother of the Long Sweeping Garment." Dress and Gender: Making and Meaning. Ed. Ruth Barnes and Joanne B. Eicher. New York/Oxford: Berg. 145-63. Print.

Hill, Michael (2008) Inca of the Blood, Inca of the Soul: Embodiment, Emotion, and Racialization in the Peruvian Mystical Tourist Industry. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 76(2): 251-279

Hill, Michael D. (2010) Myth, Globalization, and Mestizaje in New Age Andean Religion: The Intinct Churincuna (Children of the Sun) of Urubamba, Peru. Ethnohistory 57(2):263-289

Matthews-Salazar, Patricia. (2006)"Becoming All Indian: Gauchos, Pachamama Queens, and Tourists in the Remaking of an Andean Festival." Festivals, Toursism and Social Change: Remaking Worlds. Ed. David Picard and Mike Robinson. N.p.: Channel View Publications. 71-81. Print.

Molinie, Antoinette (2004) The Resurrection of the Inca: The Role of Indian Representations in the Invention of the Peruvian Nation. History and Anthropology 15(3):233-250

Murra, John V. (1962) Cloth and Its Functions in the Inca State. American Anthropologist. 64(4): 710-728