Patrol torpedo boat PT-109

| File:PT-109 Panama.png PT-109 cruising. For other photos see[1]

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | PT-109 |

| Ordered | 1942 |

| Builder | Elco, Bayonne, New Jersey |

| Laid down | 4 March 1942 |

| Launched | 20 June 1942 |

| Completed | 19 July 1942 |

| Identification | Hull symbol: PT-109 |

| Motto | They were expendable. |

| Fate | Sunk by Japanese destroyer Amagiri, 2 August 1943 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement | 56 long tons (57 t) (full load) |

| Length | 80 ft (24 m) overall |

| Beam | 20 ft 8 in (6.30 m) |

| Draft | 3 ft 6 in (1.07 m) maximum (aft) |

| Installed power | 4,500 horsepower (3,400 kW) |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 41 knots (76 km/h; 47 mph) maximum (trials) |

| Endurance | 12 hours, 6 hours at top speed |

| Complement | 3 officers, 14 enlisted men (design) |

| Armament |

|

| Armor | gunboat deck house protected against rifle bullets and splinter, some crews fitted armor plate to refrigerators |

PT-109 was a PT boat (patrol torpedo boat) last commanded by Lieutenant (junior grade) John F. Kennedy, future United States President, in the Pacific Theater during World War II. His actions to save his surviving crew after the sinking of PT-109 made him a war hero. PT-109's collision with a Japanese Destroyer contributed to Kennedy's long-term back problems and required months of hospitalization at Chelsea Naval Hospital. Kennedy's postwar campaigns for elected office referred often to his service on the PT-109.

Specifications

PT-109 belonged to the PT-103 class, hundreds of which were completed between 1942 and 1945, by Elco, in Bayonne, New Jersey. The ship's keel was laid 4 March 1942, as the seventh Motor Torpedo Boat (MTB) of the 80-foot-long (24 m)-class built by Elco, and was launched on 20 June. She was delivered to the Navy on 10 July 1942, and fitted out in the New York Naval Shipyard in Brooklyn.

The Elco boats were the largest PT boats operated by the U.S. Navy during World War II. At 80 feet (24 m) and 40 tons, they had strong wooden hulls, constructed of two layers of 1-inch (2.5 cm) mahogany planking, excellent for speed, but offering very limited protection in a firefight or torpedo attack. Powered by three 12-cylinder 1,500 horsepower (1,100 kW) Packard gasoline engines (one per propeller shaft), their designed top speed was 41 knots (76 km/h; 47 mph).[2]

To conserve space and improve weight distribution, the outboard or wing engines were mounted with their output ends facing forward, with power transmitted through V-drive gearboxes to the propeller shafts. The center engine was mounted with the output flange facing away from the boat or aft, and power was transmitted directly to the propeller shaft.[3]

The engines were fitted with mufflers on the transom (extreme rear of boat) to direct the exhaust under water, which had to be bypassed for anything other than idle speed. The mufflers were both to mask the engines' noise from the enemy, and to improve the crew's chance of hearing enemy aircraft so defensive strikes or evasive maneuvers could be made sooner. Without the mufflers, the enemy aircraft might be detected only after they fired their cannons, machine guns or dropped their bombs.[4]

Armament

Seen in PT 109's design diagram at left, the boat had a single 20 mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft mount at the rear with "109" painted on the mounting base, two open circular rotating turrets (designed by the same firm that produced the Tucker automobile), each with twin M2 .50 caliber (12.7 mm) anti-aircraft machine guns at opposite corners of the open cockpit, and a smoke generator on her transom (stern, or extreme rear in diagram). The M2's could be effective against attacking aircraft. The smoke generator was essential when operating close to enemy vessels, for protection at close range.

The day before her final mission, PT-109's crew lashed a U.S. Army 37 mm antitank gun to the foredeck (front), replacing a small, two-man life raft. Timbers used to secure the weapon to the deck later helped save their lives when used as a float – although given the events that occurred, the original life raft would have been more useful, conserving the energy of injured crew members, and providing both flares and food, essential for survival.[5][6]

Issues with Mark 8 torpedoes and radar sets

PT-109 could accommodate a crew of three officers and 14 enlisted, with the typical crew size between 12 and 14. Fully loaded, PT-109 displaced 56 tons. The principal offensive weapon was her torpedoes. She was fitted with four 21-inch (53 cm) torpedo tubes containing Mark 8 torpedoes. They weighed 3,150 pounds (1,430 kg) each, with 386-pound (175 kg) warheads and gave the tiny boats a punch believed at the time to be effective even against armored ships. The Mark 8 torpedo, however, was both inaccurate and ineffective until their detonators were recalibrated by the Navy at the end of the war, greatly limiting the Patrol Torpedo boat's ability to defend herself from larger craft or at long range. A major issue was that even in the unlikely instance they hit their target, they rarely detonated, particularly when they hit at a 90 degree angle. In contrast, the Japanese type 93 destroyer torpedoes, later called the "long lance", were faster at 45 knots, capable of an accurate 20,000 yard range, far more powerful with 1000 pounds of high explosives, and unlike the Mark 8, their detonators usually worked when they hit their target.[6]

One naval officer explained that 90% of the time, when the button was pushed on the torpedo tube to launch a torpedo, nothing happened or occasionally the motor spun the propeller until the torpedo motor exploded in the tube sending metal fragments to the deck. For safety, a torpedo mate was frequently required to hit the torpedo's firing pin with a hammer to get one to launch. Kennedy and contemporary writers noted that torpedo mates and other PT crew were inadequately trained in aiming, and firing the Mark 8 torpedoes, and were never informed of their ineffectiveness and low rate of detonation.[7]

Compounding the problems of ineffective and unlaunchable torpedoes, the PT boats had only experimental and primitive radar sets through 1943, which were at best unreliable and frequently failed to work. PT crews sometimes abandoned their radar sets, if they were issued them at all, leaving the patrol motor boat with little advanced warning of an approaching enemy craft, particularly at night or in fog conditions.[7]

Issues with speed parity with Japanese destroyers and cruisers, limited gun range, and fuel flammability

Their typical speed of 36 knots (67 km/h; 41 mph) was effective against shipping, but because of rapid marine growth buildup on their hulls in the South Pacific and austere maintenance facilities in forward areas, PT boats ended up being slower than the top speed of the Japanese destroyers and cruisers they were assigned to attack in the Solomons. Torpedoes were also useless against shallow-draft barges, their most common targets. With their machine guns and 20 mm cannon, the PTs could not return the large-caliber gunfire carried by destroyers, which had a much longer effective range. The PT's guns, however, were usually effective against aircraft and ground targets.

Because they were fueled with aviation gasoline, a direct hit to a PT boat's engine compartment usually resulted in a total loss of boat and crew, or severe burns and injuries to those few who survived. In order to have a chance of hitting their target, PT boats had to close to within 2 miles (3.2 km) for a shot, well within the gun range of destroyers. At this distance, a target could easily maneuver to avoid being hit. The PTs approached in darkness, fired their torpedoes, which often gave away their positions, but did no damage. They were then forced to flee behind the cover of their smoke screens from the fire of enemy craft.[8]

Sometimes retreat was hampered by seaplanes dropping flares to render the boats visible in darkness. They would then attack the PTs with bombs and machine gun fire. The firing of the boats' torpedoes imposed an additional risk of detection. The Elco launch tubes used 3-inch (76 mm) black powder charges to expel the torpedoes. Firing of the charge could sometimes ignite the grease with which the torpedoes were coated to facilitate their release from the tubes. The resultant flash could give away the position of the boat, particularly since PT warfare took place almost exclusively at night. Crews of PT boats were forced to rely on their smaller size, speed, maneuverability, and darkness, to survive.[6]

Ahead of the torpedoes on PT-109 were two depth charges, omitted on most PTs, one on each side, about the same diameter and directly in front of the torpedoes. Though designed to be used against submarines, they were sometimes used to confuse and discourage pursuing destroyers. With Kennedy's squadron commander, Lt. Alvin Cluster, at the wheel in storm conditions, PT-109's port Mark 6 depth charge was knocked through the foredeck unexpectedly by an inadvertent launch of the port forward torpedo. Cluster had asked Kennedy for a turn at PT 109's wheel, as he had only had experience with the older, Elco 77-foot PTs. The torpedo stayed in the tube, half in and half out on a hot run, its propellers spinning, until Kennedy's executive officer Ensign Leonard Thom deactivated it. PT 109 returned to Tulagi for repairs to the foredeck and the replacement of the depth charge.

Early operations

PT-109 was transported from the Norfolk Navy Yard to the South Pacific in August 1942 on board the liberty ship SS Joseph Stanton. It is believed PT-109 was painted a flat, dark green at Nouméa, New Caledonia after being off-loaded from Joseph Stanton. PT-109 arrived in the Solomon Islands in late 1942 and was assigned to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2 based on Tulagi island. PT-109 participated in combat operations around Guadalcanal from 7 December 1942 to 2 February 1943, when the Japanese were withdrawing from the island.

Kennedy's training in Motor torpedo boats

Despite having a chronically bad back and a history of other illnesses, John F. Kennedy used his father Joseph P. Kennedy's influence to get into the war. In 1940, the U.S. Army's Officer Candidate School had rejected him as 4-F, for his bad back, ulcers and asthma. Kennedy's father persuaded his old friend Captain Allan Goodrich Kirk, head of the Office of Naval Intelligence, to let a private Boston doctor certify his son's good health.[9] Kennedy started out in October 1941 prior to Pearl Harbor as an ensign with a desk job for the Office of Naval Intelligence. He was reassigned to South Carolina in January 1942 because of his affair with Danish journalist Inga Arvad.[10] On 27 July 1942, Kennedy entered the Naval Reserve Officers Training School in Chicago.

After completing this training on 27 September, Kennedy voluntarily entered the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons Training Center in Melville, Rhode Island, where he was promoted to lieutenant (junior grade) (LTJG). In September 1942, Joseph Kennedy had secured PT Lieutenant Commander John Bulkeley's help in placing his son in the PT boat's service and enrolling him in their training school, after meeting with Bulkeley in a New York Plaza suite near his office at Rockefeller Plaza.[11] Nonetheless, Bulkeley would not have recommended John Kennedy for PT training if he did not believe he was qualified to be a PT captain. In an interview with Kennedy, Bulkeley was impressed with his appearance, communication skills, grades at Harvard, and awards received in small boat competitions, particularly while a member of Harvard's sailing team. Exaggerated claims by Bulkeley about the effectiveness of the PTs in combat against larger craft allowed him to recruit top talent, raise war bonds, and cause overconfidence among squadron commanders who continued to put PTs against larger craft. But many in the Navy knew the truth; his claims that PTs had sunk a Japanese cruiser, a troopship, and a plane tender in the Philippines were false.[12][13] Kennedy completed his PT training in Rhode Island on 2 December, with very high marks and was asked to stay for a brief period as an instructor. He was then ordered to the training squadron, Motor Torpedo Squadron 4, to take over the command of motor torpedo boat PT-101, a 78-foot Huckins PT boat.

Kennedy's transfer to the Pacific

In January 1943, PT-101 and four other boats were ordered to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 14 (RON 14), which was assigned to patrol the Panama Canal.[14] He detached from RON 14 in February 1943, while the squadron was in Jacksonville, Florida, preparing for transfer to the Panama Canal Zone. On his own volition, Lieutenant Kennedy then contacted family friend and crony, Massachusetts Senator David I. Walsh, Chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee, who diverted his assignment to Panama, and had him sent to PT combat in the Solomon Islands, granting Kennedy's previous "change-of-assignment" request to be sent to a squadron in the South Pacific. His actions were against the wishes of his father who had wanted a safer assignment, but demonstrated Kennedy's independence and exceptional courage.[15]

The Allies had been in a campaign of island hopping since securing Guadalcanal in a bloody battle in early 1943. Kennedy transferred on 23 February 1943, as a replacement officer to Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2, which was based at Tulagi Island, immediately north of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. Traveling to the Pacific on Rochambeau, Kennedy witnessed a fierce air strike against his ship that killed the captain, and found Kennedy helping to hand shells to a supply a large gun on board, giving him his first taste of battle.[16] He arrived at Tulagi on 14 April and took command of PT-109 on 23 April. Considerable repairs were required on the boat, and Kennedy pitched in to help the crew get his ship seaworthy. On 30 May, several PT boats, including PT-109, were ordered to the Russell Islands in preparation for the invasion of New Georgia.[14]

After the capture of Rendova Island, the PT boat operations were moved north to a crude "bush" berth there on 16 June.[4] The Rendova base held the potential for its residents to contract a host of unpleasant diseases like malaria, dengue, dysentery, and elephantiasis. The Navy men stationed there also contended with cockroaches, rats, foot diseases, ear fungus, and mild malnutrition from the monotonous and mostly canned food. On his first desk assignment with the Navy after his return to the States, Kennedy suffered from the aftereffects of malaria, colitis, and chronic back pain, all caused or aggravated by his experiences in combat or during his stay at the Rendova base.[17]

From their crude base on the northern tip of Rendova Island, on a small spit of land known as Lumbari, PT boats conducted daring and dangerous nightly operations, both to disturb the heavy Japanese barge traffic that was resupplying the Japanese garrisons in New Georgia, and to patrol the Ferguson and Blackett Straits in order to sight and to give warning when the Japanese Tokyo Express warships came into the straits to supply Japanese forces in the New Georgia–Rendova area.[14]

On 1 August, an attack by 18 Japanese bombers struck the base, wrecking PT-117 and sinking PT-164. Two torpedoes were blown off PT-164 and ran erratically around the bay until they ran ashore on the beach without exploding.[18]

Crew on PT-109's last mission

The following men were aboard on PT-109's last mission:

- John F. Kennedy, lieutenant, junior grade (LTJG), commanding officer (Boston, Massachusetts).

- Leonard J. Thom, ensign (ENS), Ohio State football athlete, and excellent swimmer, executive officer (Sandusky, Ohio).

- George H. R. "Barney" Ross, ensign (ENS) On board as an observer after losing his own boat. Attempted to operate the 37 mm gun but suffered from night blindness. (Highland Park, Illinois).

- Raymond Albert, seaman 2/c, gunner. Killed in action 8 October 1943 (Akron, Ohio).[19]

- Charles A. "Bucky" Harris, gunner's mate 3/c (GM3) (Watertown, Massachusetts).

- William Johnston, motor machinist's mate 2/c (MM2) (Dorchester, Massachusetts).

- Andrew Jackson Kirksey, torpedoman's mate 2/c (TM2) Killed in collision. (Reynolds, Georgia).[20]

- John E. Maguire, radioman 2/c (RM2) (Dobbs Ferry, New York).

- Harold William Marney, motor machinist's mate 2/c (MM2). Killed in collision, manning turret closest to impact point. (Springfield, Massachusetts)[21]

- Edman Edgar Mauer, quartermaster, cook, 3/c (QM3) (St. Louis, Missouri).

- Patrick H. "Pappy" McMahon, motor machinist's mate 1/c (MM1) (Wyanet, Illinois). Only man in engine room during collision, was badly burned, but recovered from his wounds. Only member of the crew besides Kennedy mentioned by name in the song.

- Ray L. Starkey, torpedoman's mate 2/c (TM2) (Garden Grove, California).

- Gerard E. Zinser, motor machinist's mate 1/c (MM1) Erroneously called "Gerald" in many publications, Zinser remained in the Navy for a career following the end of World War II, eventually retiring as a chief petty officer. The last living survivor of PT-109, he died in Florida in 2001. (Belleville, Illinois).

Battle of Blackett Strait

At the end of July 1943, intelligence reports were received and decoded by Naval authorities at Kennedy's PT base on Tulagi's Rendova Island indicating that five enemy destroyers were scheduled to run the night of 1–2 August. The destroyers would cruise from the Solomon's Bougainville Island through Blackett Strait to supply provisions and bring troops to the Japanese garrison on Vila Plantation, on Kolombangara Island's southern tip. America's sophisticated deciphering of the Japanese naval codes had contributed to the victory at the Battle of Midway, ten months earlier, and the same technology had been used to break their code and provide the report of the Japanese destroyers expected 1–2 August. Despite the recent loss of two boats and two crewmen from a recent Japanese air attack, the skippers of PT-109 and 14 other boats met with Commander Thomas G. Warfield to discuss the details of a mission to head north through a cut in the reefs known as Ferguson Passage, to Blackett Strait between Gizo and Kolombongara Islands to block or attack the anticipated enemy destroyers. The resulting skirmish, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Blackett Strait, should not be confused with an earlier battle there on 3 March 1943. Commander Arleigh Burke had been ordered to sit on the northern approach to Kolombangara with seven American destroyers to ensure the Japanese were prevented from reinforcing their garrison, though he was not on station till 12:30 a.m. All four Japanese destroyers would evade his grasp, as they arrived one hour early, before Burke had reached his post.[22][23] The resulting battle would become the largest use of PT boats in the war, and the results would not be promising for the future use of PTs against Japanese destroyers.[4][24]

Failure of the PTs' torpedoes in action

On 1 August, fifteen PT boats, PT-109 among them, motored from the PT base on Rendova around 6:30 p.m. on strict but cursory orders from Rendova's top brass, Commander Thomas Warfield. The combined PT task force was divided into four divisions of roughly four PTs each. PT-109's "B" division included PTs 162, 159, and 157, and were stationed the farthest north of the PT divisions, nearly midway up Kolombongara Island's western coast and around 6 miles (9.7 km) to the west. Most of the divisions reached their station by 8:30 p.m. The fifteen PTs carried four torpedo tubes each, for a total of 60 Mark 8 torpedoes, and roughly half of these were fired at the four advancing Japanese destroyers protected by Japanese float planes.[25] The Navy's official report of the incident listed 5–6 torpedo explosions reaching the destroyer target, but none, in fact, were actual torpedo hits. Of the twenty-four torpedoes fired by PT boats from eight PTs, not a single hit was scored against the advancing destroyers. Though each division of PTs was assigned a location likely to intercept the destroyers, several of those without radar cruised about aimlessly in the fog and darkness, unable to locate the enemy ships.[26]

Separation of the 109 from her division

Lieutenant Brantingham on PT-159, leader of Kennedy's division, and originally stationed near Kennedy, first saw radar blips indicating the southbound destroyers just arriving on the scene, and fired his torpedoes from about a mile away. As he advanced, he did not radio Kennedy's 109 to follow, leaving Kennedy and his crew behind in the darkness. All of Brantingham's torpedoes missed the destroyers, and his torpedo tubes caused a small fire, requiring Lieutenant Liebenow's PT, also in Kennedy's division, to swing in front of Brantingham's PT to block the light emitting from his burning torpedo tubes as they could have given away their location to the destroyers. Liebenow's 157 fired two more torpedoes that failed to hit their target as well, then both boats laid smoke from their smoke generator and zigzagged away to avoid detection. No signal of the destroyer's presence was ever radioed or received by Kennedy's 109, or the other boat in the division, and skippers Brantingham and Liebenow headed blindly west to Gizo Island and away from the destroyers and Kennedy's 109.[27]

Many of the torpedoes that were fired exploded prematurely or ran at the wrong depth. The odds that a Mark 8 torpedo that made it to a destroyer would explode was less than 50%, due to faulty calibration of the detonators, a problem that was not known nor corrected by the Navy until later in the war. A few other PTs, including the leader of Division A to the south of Kennedy, intercepted the destroyers on their southbound route close to Kolombangara, but were unable to hit any with torpedoes. The boats were radioed by Warfield to return when their torpedoes were expended, but the four boats with radar fired their torpedoes first and were ordered to return to base. Commander Warfield's concept of sending orders to the PTs in darkness by radio from 40 miles away and without a view of the battle, was inefficient at best. The radar sets the four boats carried were relatively primitive, and sometimes malfunctioned. When the four boats with radar left the scene of the battle, the remaining boats, including PT-109, were deprived of the ability to determine the location or approach of the oncoming destroyers, and were not notified that other boats had already engaged the enemy.

Late in the night, Kennedy's 109 and two accompanying PTs became the last to sight the Japanese destroyers returning on their northern route to Rabaul, New Britain, New Guinea, after they had completed dropping their supplies and troops at 1:45 a.m. on the southern tip of Kolombangara.[28] The official Navy account of the incident listed radio communications as good, but PT commanders were also told to maintain radio silence until informed of enemy sightings, causing many commanders to turn off their radios or not closely monitor their radio traffic, including Kennedy.[29][30][31]

Collision with the Amagiri, 2 August

By 2 a.m. on 2 August 1943, as the battle neared its end, PT-109, PT-162, and PT-169 were ordered to continue patrolling the area on orders previously radioed from Commander Warfield.[32] The night was cloudy and moonless, and fog had set amidst the remaining PTs. Kennedy's boat was idling on one engine to avoid the detection of her phosphorescent wake by Japanese aircraft when[33] the crew realized they were in the path of the Japanese destroyer Amagiri, which was heading north to Rabaul from Vila Plantation, Kolombangara, after offloading supplies and 902 soldiers.

Contemporary accounts of the incident, particularly the work of Mark Doyle, do not conclude that the sole cause of the collision was the initial lack of speed and maneuverability caused by the idling engines of the 109. Kennedy believed the firing he had heard was from shore batteries on Kolombangara, not destroyers, and that he could avoid detection by idling his engines and reducing his wake.[29][34]

Kennedy said he attempted to turn PT-109 to fire a torpedo and have Ensign George "Barney" Ross fire their newly installed 37 mm anti-tank gun from the bow at the oncoming northbound destroyer Amagiri. Ross lifted a shell but did not have time to load it into the closed breech of the powerful weapon that Kennedy hoped might deter the oncoming vessel.[35] Amagiri was traveling at a relatively high speed of between 23 and 40 knots (43 and 74 km/h; 26 and 46 mph) in order to reach harbor by dawn, when Allied air patrols were likely to appear.[36][37]

Kennedy and his crew had less than ten seconds to get the engines up to speed and evade the oncoming destroyer, which was advancing without running lights, but the PT boat was run down and severed between Kolombangara and Ghizo Island, near 8°3′S 156°56′E / 8.050°S 156.933°E.[38] Conflicting statements have been made as to whether the destroyer captain had spotted and steered towards the 109. Most contemporary authors write that Amagiri's captain intentionally steered to collide with the 109. Amagiri's captain, Lieutenant Commander Kohei Hanami, later admitted it himself and also stated that the 109 was traveling at a steady pace in their direction.[39]

PT-109 explodes

When PT-109 was cut in two around 2:27 a.m.,[40] a fireball of exploding aviation fuel 100 feet high announced the collision, and caused the sea surrounding the ship to flame. Seamen Andrew Jackson Kirksey and Harold W. Marney were killed instantly, and two other members of the crew were badly injured and burned when they were thrown into the flaming sea surrounding the boat. For such a catastrophic collision, explosion, and fire, there were few men lost when contrasted to the losses on other PT boats hit by shell fire. PT-109 was gravely damaged, with watertight compartments keeping only the forward hull afloat in a sea of flames.[34][41]

PT-169, closest to Kennedy's craft, launched two torpedoes that missed the destroyer and PT-162's torpedoes failed to fire at all. Both boats then turned away from the scene of the action and returned to base without checking for survivors from PT-109. There had been no procedure outlined by Commander Warfield of how to search for survivors or what the PT flotilla should do in case a ship was lost.[34] In the words of Captain Robert Bulkley, naval historian, "This was perhaps the most confused and least effectively executed action the PTs had been in. Eight PTs fired 30 torpedoes. The only confirmed results were the loss of PT 109 and damage to the Japanese destroyer Amagiri" [from striking the 109].[42]

Survival, swim to Plum Pudding Island, 2 August

Kennedy was able to rescue MM1 Patrick McMahon, the crew member with the most severe wounds, which included burns that covered 70 percent of his body, and brought him to the floating bow. Kennedy also rescued Starkey and Harris, bringing them both to the bow.[43] On instructions from Kennedy, the eleven survivors thrown from the 109 first regrouped, and then hoping for rescue, clung to PT-109's bow section for 12 hours as it drifted slowly south. By about 1 p.m.,[4] on 2 August, it was apparent that the hull was taking on water and would soon sink, so the men decided to swim for land, departing around 1:30 p.m.[44][45] As there were Japanese camps on all the nearby large islands including Kolombangara, the closest, they chose the tiny deserted Plum Pudding Island southwest of where the bow section had drifted. They placed their lantern, shoes, and non-swimmers on one of the timbers that had been used as a gun mount and began kicking together to propel it. Kennedy, who had been on the Harvard University swim team, used a life jacket strap clenched between his teeth to tow McMahon.[46] It took four hours to swim to the island, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) away, which they reached without encountering sharks or crocodiles.[47][36]

Additional swims, 2, 4, and 5 August

Plum Pudding Island was only 100 yards (91 m) in diameter, with no food or water. The exhausted crew dragged themselves behind the tree line to hide from passing Japanese barges. The night of 2 August, Kennedy swam 2 miles (3.2 km) to Ferguson Passage to attempt to hail a passing American PT boat. On 4 August, he and Lenny Thom assisted his injured and hungry crew on a demanding swim 3.75 miles (6.04 km) south to Olasana Island which was visible to all from Plum Pudding Island. They swam against a strong current, and once again, Kennedy towed McMahon by his life vest. They were pleased to discover Olasana had ripe coconuts, though there was still no fresh water.[48] On the following day, 5 August, Kennedy and George Ross swam for one hour to Naru Island, visible at an additional distance of about .5 miles (0.80 km) southeast, in search of help and food and because it was closer to Ferguson Passage where Kennedy might see or swim to a passing PT boat on patrol. Kennedy and Ross found a small canoe, packages of crackers and candy, and a fifty-gallon drum of drinkable water left by the Japanese, which Kennedy paddled back to Olasana in the acquired canoe to provide his crew. It was then that Kennedy first spoke to native Melanesian coastwatchers Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana on Olasana Island. Months earlier, Kennedy had learned a smattering of the pidgin English used by the coastwatchers by speaking with a native boy. The two coastwatchers had finally been convinced by Ensign Thom that the crew were from the lost 109, when Thom asked Gasa if he knew John Kari, and Gasa replied that he worked with him.[49] Realizing they were with Americans, the coastwatchers brought a few yams, vegetables, and cigarettes from their dugout canoe and vowed to help the starving crew.[34][50] But it would take two more days for a full rescue.[51]

Rescue

The rescue of PT-109 was a long process, largely achieved by the work of native Solomon Island scouts who first located Kennedy and his crew. The scouts were sent by Sub-lieutenant Arthur Reginald Evans, an Australian coastwatcher who had seen the 109 explode from his secret observation site.

Aerial search of PT-109 sinking site

The explosion and resulting fireball on the early morning of 2 August was spotted by Evans, who manned a secret observation post at the top of the Mount Veve volcano on Kolombangara, where more than 10,000 Japanese troops were garrisoned below on the southeast portion. The Navy and its squadron of PT boats held a memorial service for the crew of PT-109 after reports were made of the large explosion, but Commander Warfield, to his credit, ordered an aerial search by Royal New Zealand Air Force P-40 fighters that spotted a few remains of the wreck, but not the crew who had already swum to safety.[36]

Coastwatchers Gasa and Kumana, 5 August

Evans had been the first to dispatch islander scouts, Gasa and Kumana, in a dugout canoe late on 5 August, to look for possible survivors after decoding radio broadcasts that the explosion he had witnessed was from the lost PT-109. Gasa and Kumana had been trained by the British and Australians in search and detection and were willing to sacrifice their lives as part of their duty to the British and American troops. Native coastwatchers were used because they could avoid detection by Japanese ships and aircraft and, if spotted, would probably be taken for native fishermen.

Before they were rescued by the scouts on 8 August, Kennedy and his men survived for six days on Plum Pudding and then Olasana Island. They had eaten only a few ripe coconuts, rainwater caught on leaves, and small amounts of fresh water and Japanese cookies Kennedy had taken from Naru Island. By chance Gasa and Kumana stopped by Naru to investigate a Japanese wreck, from which they salvaged fuel and food. They first fled by canoe from Kennedy, who with his sunburn, beard, and disheveled clothing appeared to them to be a Japanese soldier. When they later arrived on Olasana, they pointed their Tommy guns at the rest of the crew, since the only light-skinned people they expected to find were Japanese with whom they could not communicate.[34]

Thom's and Kennedy's rescue messages

Kennedy's message scratched on a coconut while he was on Naru, where he had spent some time from 4–7 August, was not the only communication given to the coastwatchers. A more detailed message was written by the executive officer of PT-109, Ensign Leonard Jay Thom on 6 August. Thom's message was a "penciled note" written on paper, which read:[52][53]

To: Commanding Officer--Oak O

From:Crew P.T. 109 (Oak 14)

Subject: Rescue of 11(eleven) men lost since Sunday, August 1 in enemy action. Native knows our position & will bring P.T. Boat back to small islands of Ferguson Passage off NURU IS. A small boat (outboard or oars) is needed to take men off as some are seriously burned.

Signal at night three dashes (- - -) Password--Roger---Answer---Wilco If attempted at day time--advise air coverage or a PBY could set down. Please work out a suitable plan & act immediately Help is urgent & in sore need. Rely on native boys to any extent

Thom

Ens. U.S.N.R

Exec. 109.[54][53]

Though the 1963 movie depicted Kennedy offering a coconut inscribed with a message as his idea and the sole form of communication, it was Gasa who suggested it and Kumana who climbed a coconut tree to pick one. On the instructions of Gasa, Kennedy painstakingly scratched the following message on the coconut husk with a knife:[34]

NAURO ISL

COMMANDER... NATIVE KNOWS POS'IT...

HE CAN PILOT... 11 ALIVE

NEED SMALL BOAT... KENNEDY[55]

Coastwatcher's canoe trip from Olsana to the PT base, 6 August

On 6 August, native coastwatchers Biaku Gasa and Eroni Kumana left Olasana and headed east, carrying the penciled note and Kennedy's coconut message ten nautical miles to Wana Wana Island, south of Kolombangara and 1/4 of the way to Kennedy's PT Naval base on Rendova Island.[56] There they took little time to rest but linked up with Senior Scout Benjamin Kevu who they told they had found the crew of the 109. Ben Kevu sent another scout to inform Reginald Evans, north on Kolombangara Island, of the discovery. Gasa and Kumana departed Wana Wana with scout John Kari in a better canoe given them by Kevu, carrying both Thom's and Kennedy's messages to a military outpost on Roviana Island, close to the PT Rendova base in a total of fifteen hours by paddling their canoe all night through 38 mi (61 km) of rough seas, and hostile waters patrolled by the Japanese. From the content of the messages, it is clear both Thom and Kennedy trusted the coastwatchers with their lives, as neither message contained the exact coordinates of their location, nor the name of Olasana Island. Traveling in an arranged boat, Gasa and Kumana were at last sent south to the PT base at Rendova from Roviana Island, a distance of only three miles from the Rendova PT base, with Gasa still clutching the coconut. Around 6 August, after speaking to Kevu about the eleven found on Olasana, Evans sent a canoe with fresh fish, yams, potatoes, corned beef hash, and rice to Kennedy and his crew with a message to return to him on Kolumbangara's Gomu Island in the canoe immediately. Kennedy followed this request and was the only one of his crew to go, since there were many Japanese planes flying above and the coast watcher's station was located on the Japanese occupied island of Wana Wana. Kennedy was instructed to lie underneath palm fronds in the canoe so he would not be spotted by Japanese planes.[57] It was not until the morning of 7 August, that Evans was able to radio Rendova to confirm the news that Kennedy and his crew had been discovered.[58]

Battle of Vella Gulf, Admiral Halsey, 6–7 August

On the night of 6–7 August, while Kennedy still awaited rescue, Admiral William Halsey, now convinced that PTs were unsuitable against Japanese destroyers, sent six U.S. Navy destroyers equipped with more advanced radar to intercept the "Tokyo Express", again on their frequent run to Kolombangara Island. This time, the U.S. forces succeeded and sank four Japanese destroyers, two of which, the Arashi and Hagikaze, had eluded Kennedy and the 14 PT crews on the night of 1–2 August. This action became known as the "Battle of Vella Gulf".[59]

PT-157 makes final rescue, 8 August

On 7 August, when the coastwatcher scouts carrying the coconut and paper message arrived at Rendova, PT Commander Warfield was at first skeptical of the messages and the trustworthiness of the native scouts Gasa and Kumana. After finally receiving Evans' radioed message of the discovery of the 109 crew, and facing overwhelming evidence that Kennedy had returned from the dead, he cautiously consented to risk two PTs to rescue them. Warfield selected PT-157, commanded by Kennedy's friend and former tentmate Lieutenant William Liebenow for the rescue, as he and his crew were experienced and familiar with the area. Liebenow later said that his crew were chosen because they were "the best boat crew in the South Pacific."[60] PT-171 would travel ahead and radio Liebenow of any sightings of the enemy. Departing just after sunset from Rendova at 7:00 p.m. on 8 August, Liebenow motored PT-157 to Reginald Evans' base at Gomu Island, off Kolombangara. To prevent making a wake, Liebenow traveled at 10-15 knots, muffled his engines, and zigzagged to prevent being tracked by planes or shore batteries. The arranged signal when Liebenow picked up Kennedy on Gomu was four shots, but since Kennedy only had three bullets in his pistol, Evans gave him a Japanese rifle for the fourth signal shot. With Kennedy aboard, PT-157 rescued the weak and hungry PT-109 crew members on Olasana Island in the early morning of 8 August, after dispatching row boats to pick them up. The 157 then motored the full crew and the coastwatcher scouts forty miles back to the Rendova PT base where they could begin to receive medical attention.[61]

Aftermath

There were reporters aboard PT-157, when they rescued Kennedy and his crew from Olasana Island. After the rescue, the New York Times announced, "KENNEDY'S SON IS HERO IN PACIFIC AS DESTROYER SPLITS HIS BOAT". Other papers wrote "KENNEDY'S SON SAVES 10 IN PACIFIC", and "SHOT FROM RUSTY JAP GUN GUIDES KENNEDY RESCUERS". All the published accounts of the PT-109 incident made Kennedy the key player in rescuing all 11 crew members and made him a war hero.[62] His father, Joseph Kennedy Sr., made sure that these articles were widely distributed, and that it was known that his son was a hero.[62] The articles focused on Kennedy's role in the incident, omitting most of the contributions of Thom, the crew, and the coastwatchers.[63][64]

Thom, Ross, and Kennedy were each awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Medal, though senior officer Lt. Commander Alvin Cluster had recommended Kennedy for the Silver Star.[65] Kennedy was also awarded the Purple Heart for injuries he sustained in the collision.[66][67] Following their rescue, Thom was assigned as commander of PT-587 and Kennedy was assigned as commander of PT-59 (a.k.a. PTGB-1).[66] Kennedy and Thom remained friends, and when Thom died in a 1946 car accident, Kennedy was one of his pallbearers.[66][36]

The PT-109 incident aggravated Kennedy's ongoing health issues. It contributed to his back problems, until his symptoms eventually progressed to a point where they were incapacitating.[68] The incident also contributed to his gastrointestinal problems.[62][55][36]

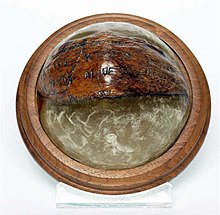

The coconut shell came into the possession of Ernest W. Gibson Jr., who was serving in the South Pacific with the 43rd Infantry Division.[69] Gibson later returned it to Kennedy.[70] Kennedy preserved it in a glass paperweight on his Oval Office desk during his presidency. It is now on display at the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts.

Gasa and Kumana in later life

Both Solomon Islanders Biuku Gasa and Eroni Kumana were alive when visited by National Geographic in 2002.[71] They were each presented with a gift from the Kennedy family.

Kennedy invited both Gasa and Kumana to his inauguration, but the island authorities gave their trip to local officials instead. Kumana and Gasa made it to the airport in Honiara, but were turned back by Solomon Island officials on the grounds that their appearance and pidgin English would be an embarrassment.[72] Gasa and Kumana gained recognition, especially after being mentioned and praised by National Geographic, and the publication of William Doyle's book on PT-109. Gasa died in late August 2005, his passing noted only in a single blog post by a relative.[73]

In 2007, the commanding officer of USS Peleliu, Captain Ed Rhoades, presented Kumana with gifts, including an American flag for his actions more than 60 years earlier.[74]

In 2008, Mark Roche visited Kumana and discussed PT-109's incident. Kumana had been a scout for the Coastwatchers throughout the war, and besides rescuing the crew of PT-109, he had rescued two downed American pilots who parachuted into the sea. Kumana noted that Kennedy visited him several times while still stationed at Rendova and always brought trinkets to swap. Kumana lived atop a cliff on his native island with his extended family. His most prized possession was his bust of President Kennedy, later given him by the Kennedy family. Kumana gave Roche a valuable family heirloom, a large piece of Kustom Money, to place on the President's grave. (Among other uses, Kustom Money was used to pay tribute to a chief, especially by placing it on the chief's grave.) In November 2008, Roche placed the tribute on the President's grave in a private ceremony. The artifact was then taken to the Kennedy Library and placed on display beside the coconut with the rescue message.[72]

Kumana died on 2 August 2014, exactly 71 years after PT-109's collision with Amagiri. He was 93.[75]

Search for the remains of PT-109

The wreckage of PT-109 was located in May 2002, at a depth of 1,200 feet (370 m), when a National Geographic Society expedition headed by Robert Ballard found a torpedo tube from wreckage matching the description and location of Kennedy's vessel.[76] The boat was identified by Dale Ridder, a weapons and explosives expert on the U.S. Marine Forensics Panel.[76]

The stern section was not found, but a search using remote vehicles found the forward section, which had drifted south of the collision site. Much of the half-buried wreckage and grave site was left undisturbed in accordance with Navy policy. Max Kennedy, JFK's nephew, who joined Ballard on the expedition, presented a bust of JFK to the islanders who had found Kennedy and his crew.

This was the subject of the National Geographic TV special The Search for Kennedy's PT 109. A DVD and book were also released.

Legacy

PT-109 and American-Japanese relations

Nine years after the sinking of PT-109, U.S. Representative John Kennedy, engaged in a race for the Senate, instructed his staff to locate Kohei Hanami, Commander of the Amagiri, the Japanese destroyer that had run down the 109. When they found Captain Hanami, Kennedy wrote him a heartfelt letter on 15 September 1952, with wishes of good fortune for him and for a long term peace between Japan and the United States. The two became friends, and Hanami subsequently went into politics in 1954, being elected as councilman of Shiokawa, and later as mayor in 1962. Hanami hoped to meet Kennedy on his next visit to Japan, and though the meeting never took place, the United States and Japan remained close allies. Years later, Caroline Kennedy accepted the post of Ambassador to Japan, holding the office from November 2013 to 18 January 2017, extending the positive relationship with Japan her father had begun after the war.[77]

PT-109 in popular culture

President Kennedy presented PT-109 tie clasps to his close friends and key staff members. Replicas of the tie clasps are still sold to the public by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston, Massachusetts. The original flag from PT-109 is now kept in the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum. The story of PT-109's sinking was featured in several books and a 1963 movie, PT 109, starring Cliff Robertson. Kennedy's father, Joe Kennedy Sr., had a role in the production, financing, casting, and writing.[78] As there were only a few 80-foot Elco PT-103-class hulls in existence by that time (none in operable condition or resembling their World War II appearance), United States Air Force crash rescue boats were modified to resemble PT-109 and other Elco PTs in the movie. Instead of the dark green paint used by PT boats in the Western Pacific theater during World War II, the film versions were painted the same gray color as contemporary U.S. naval vessels of the 1960s.

A song titled "PT-109" by Jimmy Dean reached No. 8 on the pop music, and No. 3 on the country music charts in 1962, making it one of Dean's most successful recordings.[79]

Eroni Kumana named his son "John F. Kennedy."[55] Plum Pudding Island was later renamed Kennedy Island. A controversy arose when the government sold the land to a private investor who charged admission to tourists.[79] PT-109 was also a subject of toy, plastic and radio control model ships in the 1960s, familiar to boys who grew up as baby boomers. It was still a popular 1⁄72 scale Revell PT-109 (model) kit in the 21st century. Hasbro also released a PT-109 edition John F. Kennedy G.I. Joe action figure, dressed in Navy khakis with a miniature version of the famous coconut shell.

See also

Notes

- ^ Michael Pocock. "MaritimeQuest – USS PT-109 p. 1". Maritimequest.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ PT Boat 127 Archived 18 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ American PT Boats in World War II by Victor Chun

- ^ a b c d "PT-109". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships (DANFS). USN Naval History & Heritage Command. 13 September 2002. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Scalecraft history". Scalecraft.com. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ a b c Doyle 2015, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Doyle 2015, pp. 32–172, 50–57.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 63–174.

- ^ Private doctor certified health in, Fleming, Thomas, "War of Revenge", Spring 2011, MHQ, The Quarterly Journal of Military History, p. 16.

- ^ Dallek 2003, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Met at Rockefeller Plaza in Doyle 2015, pp. 28–31

- ^ False claims in Fleming, Thomas, "War of Revenge", Spring 2011, MHQ, The Quarterly Journal of Military History, p. 17.

- ^ Bulkeley was involved in (Doyle 2015, pp. 25–31)

- ^ Walsh was involved in Doyle 2015, pp. 33–34

- ^ Dallek 2003, pp. 90–91.

- ^ "Dick Keresey, "Farthest Forward"". American Heritage Magazine. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ "Pacific Wrecks-PT-117". Pacific Wrecks, Inc. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- ^ MaritimeQuest – Raymond Albert.

- ^ "Andrew Jackson Kirksey". Find a Grave.

- ^ "Harold William Marney". Find a Grave.

- ^ Hamilton 1992, p. 557.

- ^ Dallek 2003, p. 95.

- ^ Doyle 2015, p. 73.

- ^ Donovan 2001, pp. 95, 99.

- ^ Donovan 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Hamilton 1992, p. 558.

- ^ 1:45 am in Fleming, Thomas, "War of Revenge", Spring 2011, MHQ, The Quarterly Journal of Military History, p. 19.

- ^ a b Donovan 2001, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 32–172, 72–176.

- ^ "PT-109 Loss Report". Naval History Command. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ Donovan 2001, pp. 99, 100.

- ^ Donovan 2001, pp. 60, 61, 73, 100.

- ^ a b c d e f Doyle 2015, pp. 72–176.

- ^ Donovan 2001, pp. 101, 102, 106, 107.

- ^ a b c d e Doyle 2015, pp. 134–176.

- ^ Tried to fire the anti-tank gun in Doyle 2015, p. 94

- ^ a b "Map of PT-109 Wreck Site (Kennedy)". National Geographic News. 2002. Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 96–97, 72–176.

- ^ 2:27 a.m. in Doyle 2015, p. 95

- ^ 100 foot high fireball in Doyle 2015, pp. 96–97

- ^ Bulkley, Captain Robert J., Jr. (1962). At Close Quarters PT Boats in the United States Navy. Washington, D.C. Part III Guadalcanal and Beyond -- The Solomons Campaign. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Renehan, Edward J. (2002). "Chapter 23". The Kennedys at War: 1937-1945. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

- ^ Fleming, Thomas (Spring 2011). "War of Revenge". MHQ, The Quarterly Journal of Military History.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Fleming 2011, p. 20. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFleming2011 (help)

- ^ Donovan 2001, pp. 7, 123–124.

- ^ Ballard, Robert. Collision with History: The Search for John F. Kennedy's PT 109, p. 100.

- ^ "JFK's epic Solomons swim" BBC News 30 July 2003.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 143–148.

- ^ Thom convinced the natives they were Americans in (Doyle 2015, p. 146)

- ^ Hamilton, Nigel, JFK, Reckless Youth, (1992) Random House, New York, NY, pg. 141, ISBN 0-679-41216-6

- ^ Department of the Navy – Naval History and Heritage Command, Report on Loss of PT-109 , Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ a b "Lenny Thom and PT 109". The Beacon. Schaffner Publications, Inc. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 134–176

- ^ a b c Davenport. "The Man Who Rescued JFK". Coastal Living. 17 (6): 70–77.

- ^ Hamilton 1992, p. 591.

- ^ Tregaskis, Richard (2016). John F Kennedy and PT-109. New York, NY: Open Road Media. pp. Chapter 10.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 153, 173, 156, 134–176.

- ^ Doyle 2015, p. 155.

- ^ Contrera, Jessica, "He saved JFK's life with the help of a coconut," Chicago Tribune Section 1, August 31, 2018. Obituary for William Liebenow, with quotation of WL by Contrera.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 134–176, 164–5.

- ^ a b c Giglio, James (October 2006). "Growing Up Kennedy: The Role of Medical Aliments in the Life of JFK, 1920-1957". Journal of Family History. 31: 358–385. doi:10.1177/0363199006291659.

- ^ Dallek 2003, p. 98.

- ^ Headlines in Hamilton 1992, p. 605

- ^ Thom, Ross, and Kennedy all recommended for a medal in Doyle 2015, p. 192

- ^ a b c Alcorn, William K. (25 May 2008). "Of friendship and war". The Vindicator. Youngstown, Ohio. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- ^ Siracusa, Joseph M. (7 September 2012). Encyclopedia of the Kennedys: The People and Events That Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-539-6.

- ^ Loughlin, Kevin (2002). "John F. Kennedy and his Adrenal Disease". Urology. 59: 165–169. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01206-7.

- ^ Associated Press, Troy Record, Judge's Rites Today In Vermont, 7 November 1969

- ^ Sumner Augustus Davis, Barnabas Davis (1599–1685) and His Descendants, 1973, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Chamberlain, Ted (20 November 2002). "JFK's Island Rescuers Honored at Emotional Reunion". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ a b John F. Kennedy Library (3 August 2009). John F. Kennedy Press Release.

- ^ Doyle 2015, pp. 72–176

- ^ Francis, Mike (18 September 2007). "Eroni Kumana gets his flag". The Oregonian. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Solomon Islanders mourn death of Eroni Kumana who helped save life of John F. Kennedy during WWII". Australia Network News. 4 August 2014. Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ^ a b Chamberlain, Ted. "JFK's PT-109 Found, U.S. Navy Confirms". National Geographic News. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Relationship with Hanami in Doyle 2015, pp. 212–16, 218–22, 241–42, 315–17

- ^ Hinds, Joseph (February 2011). "JFK's Other PT Boat Rescue". America in WWII: 53–57.

- ^ a b Szetu, Robertson (10 March 2005). "Kennedy Island sale to be challenged in Solomons". Pacific Islands Report. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

References

- Ballard, Robert D. (2002). Collision With History: The Search for John F. Kennedy's PT 109. Washington, D.C.: Little, Brown, and Company. ISBN 978-0-7922-6876-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dallek, Robert (2003). An Unfinished Life: John F. Kennedy, 1917–1963. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 978-0-316-17238-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donovan, Robert J. (2001) [1961]. PT-109: John F. Kennedy in WW II (40th Anniversary ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-137643-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Doyle, William (2015). PT-109: An American Epic of War, Survival, and the Destiny of John F. Kennedy. New York City: Harper-Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-234658-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fleming, Thomas (Spring 2011). "War of Revenge". MHQ, The Quarterly Journal of Military History.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flores, John W. (22 November 1998). "Last Survivor of PT 109 still grieves skipper's death". The Boston Globe.

- Hamilton, Nigel (1992). JFK, Reckless Youth. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 0-679-41216-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hara, Tameichi (2007) [1961]. Japanese Destroyer Captain. Annapolis: Naval Institute. ISBN 978-1-59114-354-3.

- Hersey, John, "Survival", in The New Yorker, 17 June 1944.

- Hove, Duane (2003). American Warriors: Five Presidents in the Pacific Theater of World War II. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press. ISBN 978-1-57249-260-8.

- Keresey, Dick (July–August 1998). "Farthest Forward". American Heritage.

- Kimmatsu, Haruyoshi (December 1970). "The night we sank John Kennedy's PT 109". Argosy. 371(6).

- Renehan, Edward J. Jr. (2002). The Kennedys at War, 1937–1945. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-50165-1.

- Tregaskis, Richard (1966). John F. Kennedy and PT-109. Garden City, NY: American Printing House for the Blind. ASIN B0007HSN7S.

- Use dmy dates from October 2012

- 1942 ships

- Conflicts in 1943

- John F. Kennedy

- Maritime incidents in August 1943

- United States Navy in the 20th century

- Naval battles of World War II involving Japan

- Naval battles of World War II involving the United States

- Pacific Ocean theatre of World War II

- PT boats

- Ships built in Bayonne, New Jersey

- Ships sunk in collisions

- World War II patrol vessels of the United States

- World War II shipwrecks in the Pacific Ocean