Phenylpropanolamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Acutrim |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Multum Consumer Information |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP2D6) |

| Elimination half-life | 2.1–3.4 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.035.349 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13NO |

| Molar mass | 151.206 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Phenylpropanolamine (BAN and INN; PPA, β-hydroxyamphetamine), also known as the stereoisomers (−)-norephedrine and norpseudoephedrine, is a psychoactive drug of the phenethylamine and amphetamine chemical classes which is used as a stimulant, decongestant, and anorectic agent.[1] It is commonly used in prescription and over-the-counter cough and cold preparations. In veterinary medicine, it is used to control urinary incontinence in dogs under trade names Propalin and Proin.

In the United States, PPA is no longer sold due to a proposed increased risk of stroke in younger women. In a few countries in Europe, however, it is still available either by prescription or sometimes over-the-counter. In Canada, it was withdrawn from the market on 31 May 2001.[2] In India human use of PPA and its formulations was banned on 10 February 2011,[3] but the ban was overturned by the judiciary in September 2011.[4]

Pharmacology

Phenylpropanolamine acts as an alpha-adrenergic receptor and beta-adrenergic receptor agonist as well as a dopamine receptor D1 partial agonist.[5]

Many sympathetic hormones and neurotransmitters are based on the phenethylamine skeleton, and function generally in "fight or flight" type responses, such as increasing heart rate, blood pressure, dilating the pupils, increased energy, drying of mucous membranes, increased sweating, and a significant number of additional effects.

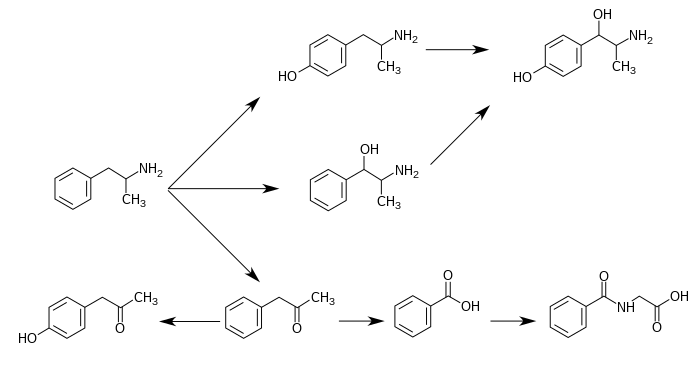

Metabolic pathways of amphetamine in humans[sources 1]

|

Legal status

In Europe, PPA is still available in prescription decongestants such as Rinexin,[17] as well as over-the-counter medications such as Wick DayMed.

In the United Kingdom, PPA was available in many 'all in one' cough and cold medications which usually also feature paracetamol or another analgesic and caffeine and could also be purchased on its own; however, it is no longer approved for human use. As of 11 August[when?], a European Category 1 Licence is required to purchase PPA for academic use.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a public health advisory[18] against the use of the drug in November 2000. In this advisory, the FDA requested that all drug companies discontinue marketing products containing PPA. The agency estimates that PPA caused between 200 and 500 strokes per year among 18-to-49-year-old users. In 2005, the FDA removed PPA from over-the-counter sale.[19] Because of its potential use in amphetamine manufacture, it is controlled by the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005. It is still available for veterinary use in dogs, however, as a treatment for urinary incontinence.

Internationally, an item on the agenda of the 2000 Commission on Narcotic Drugs session called for including the stereoisomer norephedrine in Table I of United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances.[20]

Drugs containing PPA were banned in India on 27 January 2011.[21] On 13 September 2011 Madras High Court revoked a ban on manufacture and sale of paediatric drugs nimesulide and phenylpropanolamine (PPA).[22]

Chemistry

There are four optical isomers of PPA: dextro- and levo-norephedrine, and dextro- and levo-norpseudoephedrine. d-Norpseudoephedrine is also known as cathine, and occurs naturally in Catha edulis ("Khat").[23]

Phenylpropanolamine, structurally, is in the substituted phenethylamine class, consisting of a cyclic benzene or phenyl group, a two carbon ethyl moiety, and a terminal nitrogen, hence the name phen-ethyl-amine.[24] The methyl group on the alpha carbon (the first carbon before the nitrogen group) also makes this compound a member of the substituted amphetamine class.[24] Ephedrine is the N-methyl analogue of phenylpropanolamine.

Exogenous compounds in this family are degraded too rapidly by monoamine oxidase to be active at all but the highest doses.[24] However, the addition of the α-methyl group allows the compound to avoid metabolism and confer an effect.[24] In general, N-methylation of primary amines increases their potency; whereas β-hydroxylation decreases CNS activity, but conveys more selectivity for adrenergic receptors.[24]

See also

Notes

- ^ Flavahan NA (April 2005). "Phenylpropanolamine constricts mouse and human blood vessels by preferentially activating alpha2-adrenoceptors". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313 (1): 432–9. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.076653. PMID 15608085.

- ^ "Advisories, Warnings and Recalls – 2001". Health Canada. 7 January 2009. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010.

- ^ "Drugs Banned In India". Dte.GHS, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Madras High Court revokes ban on manufacture and sale of paediatric drugs nimesulide and PPA - India Medical Times".

- ^ "Phenylpropanolamine". DrugBank. University of Alberta. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ^ "Adderall XR Prescribing Information" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Shire US Inc. December 2013. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, US: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39). ... The phase 1 metabolism of amphetamine analogs is catalyzed by two systems: cytochrome P450 and flavin monooxygenase. ... Amphetamine can also undergo aromatic hydroxylation to p-hydroxyamphetamine. ... Subsequent oxidation at the benzylic position by DA β-hydroxylase affords p-hydroxynorephedrine. Alternatively, direct oxidation of amphetamine by DA β-hydroxylase can afford norephedrine.

- ^ Taylor KB (January 1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Stereochemical course of the reaction" (PDF). Journal of Biological Chemistry. 249 (2): 454–458. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)43051-2. PMID 4809526. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase catalyzed the removal of the pro-R hydrogen atom and the production of 1-norephedrine, (2S,1R)-2-amino-1-hydroxyl-1-phenylpropane, from d-amphetamine.

- ^ Krueger SK, Williams DE (June 2005). "Mammalian flavin-containing monooxygenases: structure/function, genetic polymorphisms and role in drug metabolism". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 106 (3): 357–387. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.01.001. PMC 1828602. PMID 15922018.

Table 5: N-containing drugs and xenobiotics oxygenated by FMO - ^ Cashman JR, Xiong YN, Xu L, Janowsky A (March 1999). "N-oxygenation of amphetamine and methamphetamine by the human flavin-containing monooxygenase (form 3): role in bioactivation and detoxication". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 288 (3): 1251–1260. PMID 10027866.

- ^ Santagati NA, Ferrara G, Marrazzo A, Ronsisvalle G (September 2002). "Simultaneous determination of amphetamine and one of its metabolites by HPLC with electrochemical detection". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 30 (2): 247–255. doi:10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00330-8. PMID 12191709.

- ^ a b c Sjoerdsma A, von Studnitz W (April 1963). "Dopamine-beta-oxidase activity in man, using hydroxyamphetamine as substrate". British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy. 20 (2): 278–284. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1963.tb01467.x. PMC 1703637. PMID 13977820.

Hydroxyamphetamine was administered orally to five human subjects ... Since conversion of hydroxyamphetamine to hydroxynorephedrine occurs in vitro by the action of dopamine-β-oxidase, a simple method is suggested for measuring the activity of this enzyme and the effect of its inhibitors in man. ... The lack of effect of administration of neomycin to one patient indicates that the hydroxylation occurs in body tissues. ... a major portion of the β-hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine occurs in non-adrenal tissue. Unfortunately, at the present time one cannot be completely certain that the hydroxylation of hydroxyamphetamine in vivo is accomplished by the same enzyme which converts dopamine to noradrenaline.

- ^ Badenhorst CP, van der Sluis R, Erasmus E, van Dijk AA (September 2013). "Glycine conjugation: importance in metabolism, the role of glycine N-acyltransferase, and factors that influence interindividual variation". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 9 (9): 1139–1153. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.796929. PMID 23650932. S2CID 23738007.

Figure 1. Glycine conjugation of benzoic acid. The glycine conjugation pathway consists of two steps. First benzoate is ligated to CoASH to form the high-energy benzoyl-CoA thioester. This reaction is catalyzed by the HXM-A and HXM-B medium-chain acid:CoA ligases and requires energy in the form of ATP. ... The benzoyl-CoA is then conjugated to glycine by GLYAT to form hippuric acid, releasing CoASH. In addition to the factors listed in the boxes, the levels of ATP, CoASH, and glycine may influence the overall rate of the glycine conjugation pathway.

- ^ Horwitz D, Alexander RW, Lovenberg W, Keiser HR (May 1973). "Human serum dopamine-β-hydroxylase. Relationship to hypertension and sympathetic activity". Circulation Research. 32 (5): 594–599. doi:10.1161/01.RES.32.5.594. PMID 4713201. S2CID 28641000.

The biologic significance of the different levels of serum DβH activity was studied in two ways. First, in vivo ability to β-hydroxylate the synthetic substrate hydroxyamphetamine was compared in two subjects with low serum DβH activity and two subjects with average activity. ... In one study, hydroxyamphetamine (Paredrine), a synthetic substrate for DβH, was administered to subjects with either low or average levels of serum DβH activity. The percent of the drug hydroxylated to hydroxynorephedrine was comparable in all subjects (6.5-9.62) (Table 3).

- ^ Freeman JJ, Sulser F (December 1974). "Formation of p-hydroxynorephedrine in brain following intraventricular administration of p-hydroxyamphetamine". Neuropharmacology. 13 (12): 1187–1190. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(74)90069-0. PMID 4457764.

In species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the major metabolic pathway, p-hydroxyamphetamine (POH) and p-hydroxynorephedrine (PHN) may contribute to the pharmacological profile of the parent drug. ... The location of the p-hydroxylation and β-hydroxylation reactions is important in species where aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine is the predominant pathway of metabolism. Following systemic administration of amphetamine to rats, POH has been found in urine and in plasma.

The observed lack of a significant accumulation of PHN in brain following the intraventricular administration of (+)-amphetamine and the formation of appreciable amounts of PHN from (+)-POH in brain tissue in vivo supports the view that the aromatic hydroxylation of amphetamine following its systemic administration occurs predominantly in the periphery, and that POH is then transported through the blood-brain barrier, taken up by noradrenergic neurones in brain where (+)-POH is converted in the storage vesicles by dopamine β-hydroxylase to PHN. - ^ Matsuda LA, Hanson GR, Gibb JW (December 1989). "Neurochemical effects of amphetamine metabolites on central dopaminergic and serotonergic systems". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 251 (3): 901–908. PMID 2600821.

The metabolism of p-OHA to p-OHNor is well documented and dopamine-β hydroxylase present in noradrenergic neurons could easily convert p-OHA to p-OHNor after intraventricular administration.

- ^ "Rinexin in Farmaceutiska Specialiteter i Sverige" (drug catalog) (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ "Phenylpopanolamine Advisory" (Press release). US Food and Drug Administration. 6 November 2000. Archived from the original on 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Phenylpropanolamine (PPA) Information Page – FDA moves PPA from OTC" (Press release). US Food and Drug Administration. 23 December 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009.

- ^ Implementation of the international drug control treaties: changes in the scope of control of substances. Vienna: Commission on Narcotic Drugs, Forty-third session. 6–15 March 2000. Archived from the original on 14 August 2003.

- ^ "Unsafe Drugs- nimesulide, Cisapride, Phenylpropanolamine Banned".

- ^ "Madras High Court Revokes Ban on Manufacture and Sale PPA". Scribd.com. 13 September 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Sulzer, D.; Sonders, M.S.; Poulsen, N.W.; Galli, A. (April 2005). "Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review" (PDF). Prog. Neurobiol. 75 (6): 406–33. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. PMID 15955613.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Westfall DP, Westfall TC (2010). "Chapter 12: Adrenergic Agonists and Antagonists: CLASSIFICATION OF SYMPATHOMIMETIC DRUGS". In Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC (ed.). Goodman & Gilman's Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071624428.

CHEMISTRY AND STRUCTURE-ACTIVITY RELATIONSHIP OF SYMPATHOMIMETIC AMINES

β-Phenylethylamine (Table 12–1) can be viewed as the parent compound of the sympathomimetic amines, consisting of a benzene ring and an ethylamine side chain. The structure permits substitutions to be made on the aromatic ring, the α- and β-carbon atoms, and the terminal amino group to yield a variety of compounds with sympathomimetic activity. ...N-methylation increases the potency of primary amines ...

Substitution on the α-Carbon Atom

This substitution blocks oxidation by MAO, greatly prolonging the duration of action of non-catecholamines because their degradation depends largely on the action of this enzyme. The duration of action of drugs such as ephedrine or amphetamine is thus measured in hours rather than in minutes. Similarly, compounds with an α-methyl substituent persist in the nerve terminals and are more likely to release NE from storage sites. Agents such as metaraminol exhibit a greater degree of indirect sympathomimetic activity.

Substitution on the β-Carbon Atom

Substitution of a hydroxyl group on the β carbon generally decreases actions within the CNS, largely because it lowers lipid solubility. However, such substitution greatly enhances agonist activity at both α- and β- adrenergic receptors. Although ephedrine is less potent than methamphetamine as a central stimulant, it is more powerful in dilating bronchioles and increasing blood pressure and heart rate.{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 78 (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link)

References

- Hartung, W. H.; Munch, J. C. (1929). "Amino Alcohols. I. Phenylpropanolamine and Para-Tolylpropanolamine". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 51 (7): 2262. doi:10.1021/ja01382a044.

- Hartung, W. H.; Chang, Y. T. (1952). "Palladium Catalysis. IV.1Change in the Behavior of Palladium-on-Charcoal in Hydrogenation Reactions2". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 74 (23): 5927. doi:10.1021/ja01143a031.

- W. N. Nagai, S. Kanao, Ann. Chem., 470, 157 (1929).

- G. Wilbert, P. Sosis, U.S. patent 3,028,429 (1962).

External links

- Phenylpropanolamine Information Page at FDA.gov (update, includes earlier reports)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Phenylpropanolamine

Cite error: There are <ref group=sources> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=sources}} template (see the help page).

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).