Pinckney Marcius-Simons

Pinckney Marcius-Simons | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1867 |

| Died | July 17, 1909 Bayreuth, Germany |

| Resting place | Bayreuth, Germany |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Vaugirard College, Paris;[1] atelier of Jehan Georges Vibert |

| Known for | Paintings |

| Works | The Parsifal Tone Pictures; Seats of the Mighty; Chariot of the Sun; extra-illustrated copy of A Midsummer Night's Dream |

| Movement | Academic art; Symbolism |

| Awards | Chevalier of the Legion of Honor |

| Signature | |

| |

Pinckney Marcius-Simons (1867[2]—July 17, 1909[3]) was a New York-born artist who spent his youth in Spain, Italy, and France. He studied painting under Jehan Georges Vibert, eventually joining the painter’s household.[1] Continuing to reside in France, he exhibited at the Paris Salon at an early age and quickly established himself as a successful genre painter. In the 1890s (perhaps following a serious illness[4]), he radically changed his subject matter and technique. Sometimes classified as Symbolist,[5] his phantasmagoric later works depicted Christian religious visions, elements of Classical mythology, and scenes inspired by the operas of Richard Wagner. His works were greatly admired by Teddy Roosevelt, who owned four paintings by Maricus-Simons and called him "a great imaginative artist, a wonderful colorist; and a man with a vision more wonderful still."[6] In 1908 he was named a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor. Described from the beginning of his career as "delicate in health,"[1] he died in his forties in Bayreuth, where he was buried. In his lifetime his works fiercely divided critics and were avidly sought by collectors, but after his death he was largely forgotten.

Education and early success[edit]

Marcius-Simons was barely in his twenties when he painted The Child Canova Modeling a Lion Out of Butter[7] and Young Lulli, pendant paintings depicting two legendary child prodigies.

These and other paintings came to the attention of art critic George William Sheldon, who championed Marcius-Simons in his 1888 book Recent Ideals of American Art. "The artist was born in New York City," Sheldon wrote,

but was brought to France in infancy for his health. He is now (1888) twenty-five years old,[8] though looking scarcely more than eighteen, and has visited his native land but once since his departure from it. Slight in figure, nervous in manner, delicate in health, with regular features and an aristocratic expression, speaking English brokenly, but using it in preference to any other tongue….much of his life was spent in Spain and Italy, but his academic education was pursued at the celebrated Vaugirard College in Paris, under the direction of the Jesuits. So successful was he in his studies that he received the unusual permission to study art also during his collegiate course; and, when the distinguished painter Vibert had resolved to receive some pupils, the youngest of the group was Marcius-Simons, who had been recommended by the celebrated Detaille. The American’s health was severely tried by the resolute ambition which made him simultaneously a collegian and an art-student; and, as if still further to test it, Vibert invited him to become a member of his family after the regular term of his atelier had closed, thus giving him an extraordinary opportunity for mastering the art that he loved.[1]

His training as an artist began at age twelve, and "his first painting was signed at sixteen.…To build his cathedrals and fairy palaces, he studied architecture…To evolve scientifically evanescent angels, he studied anatomy, until the late Gérôme stopped him, saying: ‘You wish to become a painter, not a doctor!'"[3]

He made his public debut in 1891, exhibiting genre paintings at both the Paris Salon[9] and the Royal Academy of Arts in London.[10]

Works by Marcius-Simons before 1892 can be dated by the earlier, less stylized signature of his hyphenated names in all-capitals with the final stroke on the letter "R" elongated.

-

The Young Lulli, c. 1885.

-

Sarah Bernhardt as La Tosca, 1887 or 1888.

-

Les Premières Voiles, 1891.

-

A Flirtation (auction title), before 1892.

-

The Ambitious Model (auction title), before 1892.

-

Lost in Her Thoughts (auction title), before 1892.

-

Woman with a Fan Reading (auction title), before 1892.

Transition to Symbolism[edit]

At the Paris Salon of 1892, Marcius-Simons exhibited Mon royaume n’est pas de ce monde (My Kingdom Is Not of This Earth). The style still reflected the precision of his academic training, but the imagery was hallucinatory. The painting also bore the distinctive signature he would use thereafter. Mon royaume… drew both praise and derision. Alexandre Hepp called it "a great painting," and Marcius-Simons "a great mystical artist."[11] Étienne Durand saw a depiction of

the reverie of the principle figure dressed in red, a prince of the church…Around him, like motes populating a ray of sunshine, crowd together the most disparate visions, capable satisfying all human passions and appetites: love, ambition, avarice, sensuality, dissipation, etc. In a corner, the divine child, sleeping in his crib, shines with a bright halo; above him, vague and diaphanous forms of celestial beings glide in the radiance of the stained glass windows. It is a bizarre composition that seems at first sight incoherent, like a feverish hallucination, but which becomes clearer as one studies it and discovers, rendered with astonishing clarity, the moral kaleidoscope of meditation. As for the painting, it is extraordinarily elegant, precise and brilliant.[12]

But a British critic was not impressed. "So faulty in this matter is the design, the eye travels in puzzled and bewildered amazement…The discovery of the Christ-child…elucidates the mystery, but it in no wise explains why Mr. Marcius-Simons, who obviously has the gift of imagination, should be so wofully lacking in style."[13]

In 1893 he exhibited Chant du Cygne at the Salon; The New York Times wrote that Marcius-Simons "is astonishing by the constant evolution of his own personality."[14] But in a plea for "A Sane View," James Stanley Little dismissed Marcius-Simons as a passing fashion.[15]

Also in 1893 he exhibited at the Salon de la Rose + Croix in Paris, curated by Joséphin Péladan, an avant-garde showcase for artists, writers, and composers that grew out of Péladan's cultic religious movement, the Mystic Order of the Rose + Croix. Marcius-Simons subsequently exhibited at three more of Péladan’s salons.[16] His ties to Rosicrucianism would draw censure from some quarters.[17]

Léon Roger-Milès, reviewing La Rayonnement de la Croix and La Parabole des Vierges at the Paris Salon of 1894, called Marcius-Simons "exceptionally gifted…a mystic who brings to the end of our century a distant echo of the imaginations of the fourteenth century."[18]

-

Mon royaume n’est pas de ce monde, 1892.

-

Le Chant du Cygne, 1893.

-

Les Bâtisseurs de la ville (La Renaissance), 1897.

Avery Art Galleries shows and reception in the United States[edit]

These striking new works attracted the interest of the influential New York connoisseur and art dealer Samuel Putnam Avery, famous for having introduced the paintings of Turner to America.[11] Avery mounted Marcius-Simons' first solo exhibit of twenty works at the Avery Art Galleries in 1895. By this time, the artist's style, tone, and subject matter had changed completely from his beginnings as a light-hearted genre painter, as exemplified by the nightmarish allegory Les Courtesanes.[19] A French critic described his works as "mystical," "strange," and "always eccentric."[20]

The 1895 Avery show was panned by some critics. The Art Interchange said the paintings "were for the most part weird fantasies of an uncontrolled imagination, wild vagaries of color, with unrelated titles…Stress has been laid on the artist's fertility of imagination, but imagination unbalanced is a doubtful gift."[21] The Art Collector noted wryly that the Marcius Simons (without a hyphen) who "commenced as a painter of genre" had emerged "full fledged into Pinckney Marcius-Simons, in quite another light.…He did so, says his biographer, after 'a serious illness,' which confined him to the solitude of his studio. To judge from the results, it must have been a very serious illness indeed…"[22]

But The New York Times, noting that the exhibit had "occasioned no little discussion and comment," said that Marcius-Simons' "ideas are entirely original, extremely personal, and of a curiously symbolic nature. Little art of this order has as yet reached this city, but in Paris the Rose Croix and other exhibitions…have given the men of impressionistic ideas and methods free scope…The twenty pictures at Avery’s are exceedingly interesting…and in them are combinations of color effects entirely his own."[23]

A second Avery Art Galleries show in New York, of 36 works, followed in 1896; the catalogue is available online.[24] The New York Times wrote that "his work in these symbolic pictures is a realization of the impossible.…He has succeeded in evolving astonishingly brilliant effects of color…And above all, he is exceedingly interesting."[25]

In 1897, his works appeared at Thurber's in Chicago. "Though the painter is very young," wrote The House Beautiful, "his reputation is firmly established as one of the most original and daring representatives of American art…the school of the Rose et Croix [and] all its eccentricities are willingly forgiven when one finds that it has rendered vocal the genius of such a man as Pinckney Marcius-Simons," whose works "have that strange clutch upon one's feelings that Turner's masterpieces had."[26] Gabriel Mourey, on the other hand, asserted that Marcius-Simons "feebly imitates the great Turner."[27]

When the paintings appeared in Boston, Poet-Lore declared his work "essentially modern and as supreme in its own way as any art that ever has been."[28]

-

Les Courtisanes, 1894.

-

And Angels Led the Way, exhibited 1896.

-

Possibly Wild Flowers, exhibited 1896.

Sought by collectors[edit]

Along with critical attention, the works attracted collectors. In 1898, Munsey’s Magazine noted that "Mr. Marcius-Simons will have no exhibition of his pictures in New York this year, for a rather curious reason. He has sold everything in his Paris studio almost as fast as it was painted."[29] In this year, his "chromatic fantasy" A Dream of Youth was reported in the collection the American silk tycoon Catholina Lambert.[30] His The Chariot of the Sun was owned by James S. Inglis of Cottier and Company.[31] Seats of the Mighty (later gifted to Teddy Roosevelt) was in the collection of Lord Arthur Hamilton Lee in London.[32] The International Studio wrote, "There are few private collectors who have not at least one example of his talent."[33]

The eminent collector Camille Groult, "the most difficult man in France to please,"[34] "was one of his patrons, and bought many of his pictures. "There is a legend that Groult, who was devoted to Turner, first bought the place commanding the view at St. Cloud painted by the Englishman,[35] and, years afterward, discovering Marcius-Simons, commissioned him to come down and paint the same subject."[36]

-

Stones of Venice, between 1902 and 1905.

-

Chariot of the Sun, by 1909.

-

Fairies (auction title), by 1909.

-

Towering Cathedral (auction title), by 1909.

-

City of Dreams (auction title), by 1909.

-

Symbolist landscape, by 1909.

The Wagnerian paintings[edit]

At some point in the 1890s, Marcius-Simons became "a fervent Bayreuthian,"[37] frequently attending the annual Bayreuth Festival of Richard Wagner's operas.[38] As early as 1893, working in both Paris and Bayreuth,[39] he began a series of paintings inspired by Wagner's work. The first exhibition of this labor, The Parsifal Tone Pictures, opened in 1904 at the Knoedler gallery in New York. The exhibit catalogue featured extensive essays on the artist's conception and methodology, including a brief section written by Marcius-Simons himself.[40]

"For ten years," wrote Louis Vauxcelles, "Marcius-Simons has been living at the heart of the Wagnerian œuvre. He has just completed eight paintings, illustrating Parsifal…the precision, the meticulousness of the Wagnerian interpretation is extraordinary.…The only influences I see in this mysterious painting are Claude Lorrain's golden twilights; Turner's blazes and fires; the figures of Gustave Moreau…and the drawing of some faces evokes perhaps the Anglo-Saxon type of Burne-Jones’ ephebes. Despite these echoes, Marcius-Simons is a singular young master."[37]

Cosima Wagner reportedly approved of the paintings.[41][42] But The New York Times found them "confusing, disconcerting," saying, "These pictures of an opera leave one cool."[43]

The Parsifal Tone Pictures were shown in other American cities, including Boston,[44] Worcester,[45] and Toledo,[46] and in 1907 they traveled to Munich.[47]

While working on the Parsifal paintings, Marcius-Simons was simultaneously at work on paintings inspired by Wagner's cycle of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen. Though he continued to work on this project up to his death, in Bayreuth, no exhibition resulted. Studies and fragments of this vast undertaking have occasionally appeared in the decades since his death.[48]

-

Le Graal, by 1904.

-

Parsifal and the Knights of the Holy Grail, by 1904.

-

L’Apparition du Graal à Perceval, by 1904.

-

Parsifal, by 1904.

-

Apotheosis, by 1904.

-

La legende de Niebelungen, les Nornes, by 1909.

Marcius-Simons and Teddy Roosevelt[edit]

In March 1904, Marcius-Simon, at his home in Paris, learned that his painting Where Light and Shadow Meet had been purchased by Teddy Roosevelt, then President of the United States. In a letter dated March 8, Marcius-Simon wrote to Roosevelt: "It is hard for me to express adequately the great pleasure, the help in my life's work, that your appreciation of my art has been to me." He proceeded in several paragraphs to put forth his ideas about art. "As a painter, I stand at the point where the definition between music and pictorial art is lost.…Using the chromatic scale to produce new harmonies of shades and varieties of color, I create as I go, handling my palette to express thoughts through the medium of the painted objects." He concluded, "Such being my convictions, my life struggle and my aim, you can imagine, Mr. President, what the revelation that you have long known and appreciated my efforts, though the possessions of friends, and that you now own one of the finest examples of my brush, has been to me."[49]

Roosevelt replied in a letter dated March 19, 1904:

Your letter pleased and interested me much. The first work I saw of yours was the Seats of the Mighty, and it impressed me so powerfully that I have ever since eagerly sought out any of your pictures of which I heard. When I became President, Mrs. Roosevelt and I made up our minds that while I was President we would indulge ourselves in the purchase of one really first-class piece of American art-for we are people whom the respective sizes of our family and our income have never warranted in making such a purchase while I was in private life! As soon as we saw When [sic] Light and Shadow Meet we made up our minds at once and without speaking to one another that at last we had seen the very thing we wanted.…When I look at [your paintings] I feel a lift in my soul; I feel my imagination stirred. And so, dear Mr. Simons, I believe in you as an artist and I am proud of you as an American."[50]

Marcius-Simons followed up by dedicating to Mrs. Roosevelt and making a gift of his painting Victory, which he described as "the olive branch tendered to the world but enforced by the sword of justice and might beneath." Edith Roosevelt described the painting in a letter to her sister Emily Carow: "The color is quite beautiful and the picture will always be interesting historically."[51]

Seats of the Mighty, mentioned by Roosevelt, was a painting he had seen and admired at the home of his friend Lord Arthur Hamilton Lee in London.[52] In 1908, Lee made a gift of the painting to Roosevelt, who in a letter to Lee called it "the source of greater delight to me than any present I ever remember receiving…We have another Simonds [sic], a very beautiful and striking picture [Where Light and Shadow Meet], altho not to me quite as wonderful a picture as The Seats of the Mighty." In a letter to Lee from the following year, Roosevelt wrote, "At this moment I am sitting in the North Room [at Sagamore Hill] where of all things that I care for—and I care for many—the one I care for most is the picture that you gave me."[32]

At some point Roosevelt acquired another Marcius-Simons painting, The Porcelain Towers. All four continue to be displayed at Roosevelt's home, now the Sagamore Hill National Historic Site.

After the death of Marcius-Simons, Roosevelt wrote:

Many Americans of wealth have rendered real service by bringing to this country collections of pictures by the masters of painting. But all of these men of wealth who have brought over paintings to this country, put together, have not added to the sum of productive civilization in this country as much as that strange, imaginative genius, Marcius-Simons, who was utterly neglected in life, who isn't known in death, but who will assuredly be known to generations that come after us as perhaps the greatest imaginative colorist since Turner.[53]

-

Seats of the Mighty, before 1904.

-

Where Light and Shadows Meet, by 1904.

-

Victory, 1904.

-

Porcelain Towers, c. 1905-1909.

A Midsummer Night's Dream[edit]

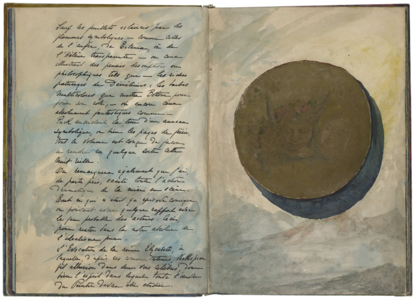

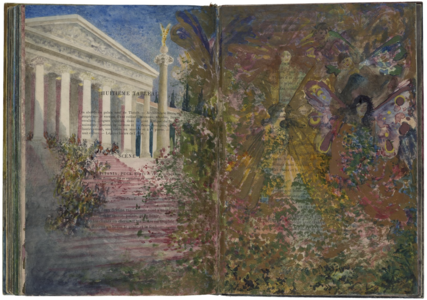

Among his last works, created in the year before his death, was an extra-illustrated book: a copy of the Paul Meurice 1886 French translation of Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream covered inside and out with watercolors painted by Marcius-Simons in 1908, while in Bayreuth. Since 1924 this object has been in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., which exhibited it in 1992 and 2001 and has made all the images available online.[54] The Folger describes the object: "The subject matter of the paintings is abstractly illustrative, often featuring symbols in passages rather than actions. There are many portrayals of the moon juxtaposed with the sun.…Much of the work portrays elements of the natural and supernatural world."

Considering that Marcius-Simons may have been in declining health at the time it was created, the decoration of this book would have provided a close-at-hand, even bed-ridden, means for him to express his art when unable to work on the large canvasses of his Wagnerian project. It is nonetheless an ambitious work and an accomplishment inversely proportional to its small physical dimensions. A French critic called it a work of "the most refined art and the most extraordinary insight…a bibliophile's exemplar of sumptuous opulence."[55][56]

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, title page, 1908.

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, page 1, 1908.

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, pages 6–7, 1908.

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, page 28-29, 1908.

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, page 46-47, 1908.

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, page 74-75, 1908.

Personal life and appearance[edit]

There are no known portraits of Marcius-Simons; his appearance is known only from written sources. George William Sheldon in 1888 described him as a man of twenty-five who looked "scarcely more than eighteen.…Slight in figure, nervous in manner, delicate in health, with regular features and an aristocratic expression."[1] Alexandre Hepp recounted a visit in 1896: "He receives me in a long brown dressing gown belted with a knotted cord, a bit like Balzac, with only his head and hands visible."[11] Hepp notes his thick, black, expertly scalloped hair, his thin lips, and slender hands ornamented with rings. Louis Vauxcelles, paying a call on the artist in 1903, described "his emaciated face, his eyes shining with fever, his weary forehead, his wasted hands."[37]

All three writers noted his preference for seclusion, Sheldon saying that "when he lays down his brush, his favorite companion is a book."[57] Vauxcelles calls him "a loner" and compares him to a medieval, reclusive monk in a cloister.[37] Vauxcelles and Hepp both note his disinterest, even disdain, for the fame and followers so avidly sought by other artists. "In the immensity of Paris" writes Hepp, "he has the charm of wishing to know no one, of aiming for the approval of only a few."[11]

Speaking of his working habits, Marcius-Simons told Hepp he would sometimes put a canvas aside for three years and then, waking one morning, come back to it, painting automatically, as if another hand controlled his brush.[11]

Against the image of Marcius-Simons as a frail loner is his appearance in a "Liste des Candidats" in 1895 for a bicycling club in France.[58] Keyzer says he was "known in the art world as Pinkey."[33][59]

Death and legacy[edit]

On January 15, 1909, Marcius-Simons was named a Chevalier of the Légion d'Honneur.[60] His enjoyment of the honor was short-lived. On July 17, 1909, in Bayreuth,[3] Marcius-Simons "still had his brush in his hand, interpreting Wagner, when death struck him."[34] He wished to be buried in Bayreuth, next to Franz Liszt, and "his wish was granted," with "a small tombstone inscribed in French" next to the monument of Liszt.[61][62]

As an expatriate American artist in Europe, Marcius-Simons considered himself a fish out of water. He wrote to Teddy Roosevelt, "In England, my paintings and methods are considered French. In France, I am an Anglo-Saxon." He himself considered his works to be "American in their essence, born and bred in the blood of generations of ancestors, natives of the States."[49] At the time of his death, American Art News said that he was "recognized in America, his home, as the foremost leader of national ideals," where "his work has become familiar to all."[3]

His later, visionary works were repeatedly compared to those of Turner, sometimes favorably (as by Teddy Roosevelt[63]), sometimes not (as by Mourey[27]). At least one critic found the comparison irrelevant.

Our first impression of Marcius-Simons' work is a curious one; we are involuntarily reminded of Turner. But this impression is only momentary, for we at once discover that the similarity lies in the subject and even in the colouring, but not in the treatment. Like Turner, he is a remarkable colourist, and reproduces colour a thousand times more beautiful than that seen by the untrained eye…In character, however, they are widely apart, and after a while we are even surprised that we should have linked them together.[64]

The same writer went on to say, "As an artist he has not always been understood…but to the great majority, an artist with elevated thoughts will always be beyond their comprehension."[64]

The author of his death notice in Le Gaulois (possibly Alexandre Hepp, who had championed his work in the paper before), hoped that the French State, which had neglected to collect his work for museums despite his elevation to the Légion d'Honneur, would "soon give him the place which belonged to an artist who more than once approached the sublime," and looked forward to a posthumous exhibit that would acknowledge the loss of one the art world's "most original creators."[34] But neither of these things took place. Marcius-Simons, a lifelong loner who died young, soon fell into obscurity on both sides of the Atlantic.

In museums and collections[edit]

- The Child Canova Modeling a Lion Out of Butter, c. 1885, Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA.

- Les Courtesans, c. 1894, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington.

- Parsifal, by 1904, La Salle University Art Museum, Philadelphia, PA.

- Four paintings at Sagamore Hill National Historic Site, Cove Neck, New York: Seats of the Mighty, before 1904; Where Light and Shadow Meet, by 1904; Victory, 1904; and The Porcelain Towers, c. 1905-1909.

- Extra-illustrated copy of A Midsummer Night's Dream, 1908, Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington, D.C.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Sheldon, p. 28.

- ^ Les Courtesans, Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington; a primary source for this date has not been located.

- ^ a b c d "P. Marcius Simons" (obituary), American Art News.

- ^ Anonymous (1895a).

- ^ Anonymous (1897).

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1913), p. 358.

- ^ Now at the Chrysler Museum of Art.

- ^ This reckoning conflicts with the birth year usually given for Marcius-Simons' birth, 1867.

- ^ The painting was Les Premières voiles—retour de la pêche du hareng (Hébrides); see Catalogue Illustré…1891, pp. XVIII and 64.

- ^ The painting was Crushed Hopes; see Royal Academy of Arts (1891), p. 63.

- ^ a b c d e Hepp (1896).

- ^ Durand (1892).

- ^ Dixon (1892).

- ^ L.K., "The New Salon of Paris" in The New York Times, June 19, 1893, p. 9.

- ^ Little (1894), p. 71.

- ^ M-S’s works at the SdR+C included Esquisse and L'âge de la Foi, 1893; Jeanne d'Arc (L'Attente), La Fièvre, La Tentation, Le Jour, Saint Georges et le Dragon (Légende), Vous, coeurs aimants! (gouache), 1894; Fleur de France, 1895; La Soif de l'Or and Les Bâtisseurs de la ville (La Renaissance), 1897.

- ^ Anonymous (1895a): "Mr. Pinkney Marcius-Simons…when he comes to glorifying the rotten race of the Bourbon kings, and presenting as claimants to martyrdom the ermined and crowned savages whose very blood stank as it filled their putrid bodies, he is a—Rosicrucian indeed."

- ^ Roger-Milès (1894).

- ^ Knauff (1895): "The Courtesans shows a frivolous crowd, gay, happy, clad in costly garments of many hues. They laugh and dance through the streets of a Grecian town, to an imposing flight of broad, marble steps, down which they wend their way, smiling, heedless, not looking ahead. But they dance to their doom. The stairway ends in a dreadful pool, the black and slimy waters of oblivion. At one side a gaping monster waits in shadow. Before us we see upturned faces, no longer filled with laughter, staring vacantly as they that float unknown, uncared for."

- ^ Bouyer, L. Raymond (1894-1895).

- ^ Anonymous (1895b).

- ^ Anonymous (1895a); the quotation regarding "serious illness" appears to be from the Avery Art Galleries 1895 exhibit catalogue, which is untraced. A causal link between a critical illness and the change in Marcius-Simons' paintings is suggestive, but has not been established.

- ^ Anonymous (1895c).

- ^ Marcius-Simons (1896)

- ^ Anonymous (1896a).

- ^ Anonymous (1896b).

- ^ a b Mourey (1897).

- ^ Anonymous (1897), p. 318.

- ^ Anonymous (1898a).

- ^ Anonymous (1898b); the painting is described in Catalogue of the Valuable Paintings… (1916), item 183.

- ^ Deluxe Illustrated Catalogue… (1909), item no. 40, with illustration

- ^ a b Wallace (1990), pp. 114-115.

- ^ a b Keyzer (1898), p. 250.

- ^ a b c Anonymous (1909).

- ^ This refers to Turner's painting Pont de St. Cloud; see Gimpel, René, Journal d'un Collectionneur Marchand de Tableaux, 1963, p. 39.

- ^ Cortissoz (1923), pp. 335-336.

- ^ a b c d Vauxcelles (1903).

- ^ Marcius-Simons is listed among the attendees at Bayreuth in 1901; see Lavignac (1903), p. 613.

- ^ Marcius-Simons (1904), p. 4.

- ^ Marcius-Simons (1904); the section headed "The Small Paintings" (pp. 19-20) ends with the byline "(Signed) MARCIUS-SIMONS".

- ^ Phelps (1904): "Simons claims…direct inspiration in meanings and interpretation from Siegfried Wagner and his mother, especially the latter.…Frau Wagner sets her seal upon his interpretations…."

- ^ Anonymous (1907): The New York Herald cites "the ties of deep friendship that unite him to the Wagner family."

- ^ Anonymous (1904).

- ^ Gallery advertisement, Programs, Boston Symphony Orchestra, 24th season, 1904-1905, pp. 100 and 164.

- ^ Report of the Trustees…, Worcester Art Museum, 1906, p. 9.

- ^ see "Exhibitions," Toledo Museum of Art, American Art Directory, vol 5., 1905, p. 271, and a first-person account of the packed audience in Stevens, Nina Spaulding, A Man & a Dream; the Book of George W. Stevens, pp. 76-77.

- ^ Anonymous (1907).

- ^ Les Filles du Rhin, a 540 x 720 mm oil on canvas from a private collection, was included in the exhibition Wagner et la France at the Théâtre National de l'Opéra in Paris in 1983; see Kahane, Martine, and Wild, Nicol, Wagner et la France, Paris: Herscher, catalogue no. 376, p. 136, which also mentions another work by Marcius-Simons titled La Chevauchée des Walkyries.

- ^ a b Letter from Pinckney Marcius-Simons to Grover Cleveland [sic] at the Theodore Roosevelt Center at Dickinson State University, North Dakota.

- ^ Bishop (1920), p. 326.

- ^ "Victory". artsandculture.google.com. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Seats of the Mighty is also mentioned in The Parsifal Tone Pictures, p. 3.

- ^ Roosevelt (1926), p. 333; Marcius-Simons is also mentioned on p. 151

- ^ "Pinckney Marcius-Simons Illustrations to A Midsummer Night's Dream". collections.folger.edu. November 11, 2022.

- ^ Anonymous (1909), who also says that at the time of his death Marcius-Simons was at work on a similarly illustrated copy of Shakespeare's The Tempest; the location of this work is unknown.

- ^ For his patron Samuel P. Avery, Marcius-Simons designed a cover for the new binding of a 1751 edition of the poems of Thomas Gray, as described in the Anderson Galleries catalogue for the Nov. 10, 1919, auction of items from the Library of the Late Samuel P. Avery, Sale Number 1441, lot 403, p. 68: "A magnificent modern binding, the design for the covers being by P. Marcius-Simons, and executed by Meunier. Inserted are 3 original designs by Marcius-Simons, one of which was used. There is also, an Autograph Letter from him to Mr. Avery, about the designs." American Book-Prices Current, Vol.26 (1920), p. 355 noted that the book sold for $110.

- ^ Sheldon, p. 30.

- ^ Touring-Club France, Année 6, No. 7, July 1895, p. 524.

- ^ The 1901 edition of Tout-Paris, p. 343, lists him as "Marcius-Simons (Pinky)."

- ^ "Nouvelles" in La Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, No. 5, january 30, 1909. p. 33.

- ^ "Nos Échos" in La Liberté, August 6, 1936, p. 2.

- ^ "Toutes Les Coulisses: Au Cimetiére de Bayreuth" in Comœdia, June 8, 1936, p. 1.

- ^ Roosevelt (1926), p. 333.

- ^ a b Keyzer (1898), pp. 250-251.

Sources[edit]

Anonymous[edit]

- Anonymous (1895a). "The Winds of March" in The Art Collector, vol. VI, no. 9, March 1, 1895, p. 144.

- Anonymous (1895b). Untitled gallery notice, The Art Interchange, vol. XXXIV, no. 4, April, 1895, p. 108.

- Anonymous (1895c). "In the World of Art" in The New York Times, February 24, 1895, p. 24.

- Anonymous (1896a). "Pictures by Marcius-Simons" in The New York Times, February 9, 1896, p. 4.

- Anonymous (1896b). The House Beautiful, December, 1896, pp. 28 and 83.

- Anonymous (1897). "The Symbolist Pictures of P. Marcius Simons" in Poet-Lore, vol. IX, no. 2, 1897, pp. 316–319.

- Anonymous (1898a). "A Painter of Allegories' in Munsey's Magazine, vol. XVIII, no. 6, March, 1898, p. 809-810.

- Anonymous (1898b). "A Silk Manufacturer's Picture Gallery" in The American Silk Journal, vol. XVII, no. 7, July, 1898, p. 30.

- Anonymous (1904). "'Parsifal' in Paintings" in The New York Times, January 21, 1904, p. 9.

- Anonymous (1907). "Exposition d'un Peintre Américain à Munich"] in The New York Herald, Paris, August 25, 2907, p 6.

- Anonymous (1909). "Coup de Crayon" in Le Gaulois, August 8, 1909, p. 1.

Catalogues[edit]

- Catalogue Illustré des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture et gravure exposés aux Champs-de-Mars, le 15 Mai 1891 (Paris Salon 1891), Paris: A. Lemercier & Cie., pp. XVIII and 64.

- Catalogue of the Valuable Paintings and Sculptures by the Old and Modern Masters, Forming the Famous Catholina Lambert Collection…, New York: The American Art Association, 1916, item 183: A Dream of Youth.

- Deluxe Illustrated Catalogue of Paintings…to be sold to facilitate the settlement of the estate of the late James S. Inglis of Cottier and Company, New York: J.J. Little and Ives, 1909, item no. 40, with illustration.

Obituaries[edit]

- "P. Marcius Simons" (obituary), American Art News, vol. 7, no. 34, August 14, 1909, p. 2.

Sources by author[edit]

- Cortissoz, Royal (1923). American Artists, New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1923, pp. 335-336.

- Bouyer, L. Raymond (1894-1895). "Les Arts" columns dated December 31, 1894, January 25, 1895, and March 27, 1895 in L’Ermitage, vol X, January-June 1895, Genève: Slatkine Reprints, 1968.

- Bishop, Joseph Bucklin (1920). Theodore Roosevelt and His Time Shown in His Own Letters, New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1920.

- Chassevent, Louis (as "Louis de Lutèce") (1897). "Aux Salon de la Rose + Croix" in Le Coloriste Enlumineur, year 5, no. 2, June 1897, p. 15.

- Dixon, Marion Hepworth (1892). "Recent Fashions in French Art: I" in The Art Journal, 1892, pp. 328-330, including image.

- Durand, Étienne (1892). "Des Champs-Elysées à l'Opéra", Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France, June 14, 1892, pp. 1–2.

- Hepp, Alexandre (1896). "Une Journée d'Art" in Le Gaulois, December 28, 1896, p. 1.

- Keyzer, Frances (1898). "Some America Artists in Paris" in The International Studio, vol. 4, 1898, pp. 246-252.

- Knauff, Christopher W. (1895). "An Artist with a Message" in The Living Church, March 23, 1895, pp. 924–925.

- L.K. (initials only). "The New Salon of Paris" in The New York Times, June 19, 1893, p. 9.

- Lavignac, Albert (1903). Le Voyage Artistique à Bayreuth, Paris: Librairie Ch. Delagrave, cinquième édition, 1903, p. 613.

- Little, James Stanley (1894). "A Sane View of Art Limitations" in The Artist, vol. 15, March 1, 1894, pp. 67–74.

- Marcius-Simons, Pinckney (1896). The P. Marcius-Simons oil paintings: on free exhibition at the Avery Art Galleries, from February seventh to February twenty-second, 1986, inclusive; Symbolistic paintings, New York: Avery Art Galleries, 1896.

- Marcius-Simons, Pinckney (1904). The Parsifal Tone Pictures, catalogue for the exhibit at M. Knoedler & Co., 355 Fifth Avenue, N.Y., opening Saturday, January 16; New York: Gorick Art Press, 1904.

- Monroe, Lucy (1897). "Chicago Notes" in The Critic, vol. 30, January 2, 1897, p. 134.

- Mourey, Gabriel (1897). "Studio Talk" item signed "G.M." in The International Studio, May, 1897, p. 198.

- Phelps, George Turner (1904). "On the Staging of Parsifal" in Poet Lore, vol. XV, no. IV, winter, 1904. pp. 104-105.

- Roger-Milès, Léon (1894). Le Salon de 1894, Paris: Boussod, Valadon, & Cie, v.7, p. 54.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1913). Theodore Roosevelt, an Autobiography, New York: Macmillan, 1913.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1926), Literary Essays, New York: Charles Scribner's Son, 1926.

- Royal Academy of Arts (1891). Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, MDCCCXCI, the One Hundred and Twenty-Third, London: The Academy, p. 63.

- Sheldon, George William. Recent Ideals of American Art, D. Appleton & Company, 1888.

- Vauxcelles, Louis (1903). "Petites Visites" in Gil Blas, December 1, 1903, p. 1.

- Wallace, David H. (1990). Sagamore Hill: Historic Furnishings Report, Vol. 1, Harpers Ferry Center, National Park Service, 1990.