Igneous intrusion

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2010) |

In geology, a pluton is a body of intrusive igneous rock (called a plutonic rock) that is crystallized from magma slowly cooling below the surface of the Earth. While pluton is a general term to describe an intrusive igneous body, there has been some confusion around the world as to the definition of a pluton.[1] Pluton has been used to describe any non-tabular intrusive body, and batholith has been used to describe systems of plutons. In other literature, batholith and pluton have been used interchangeably. In central Europe, smaller bodies are described as batholiths and larger bodies as plutons. In practice the term pluton most often means a non-tabular igneous intrusive body. The most common rock types in plutons are granite, granodiorite, tonalite, monzonite, and quartz diorite. Generally light colored, coarse-grained plutons of these compositions are referred to as granitoids. Examples of plutons include Denali (formerly Mount McKinley) in Alaska; Cuillin in Skye, Scotland; Cardinal Peak in Washington State; Mount Kinabalu in Malaysia; and Stone Mountain in the US state of Georgia.

Classification

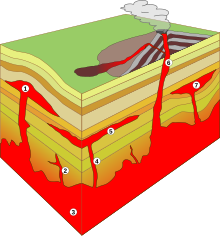

Intrusive bodies of igneous rock can be classified from one distinctions. If the body is tabular or not. The bodies can be further classified based on their shape and their concordancy with the surrounding country rocks. A tabular body is magma that has filled in a fracture or another plane of weakness. A non-tabular body however, can vary in shape much more than tabular bodies and tend to be much larger. A concordant body is one that does not cross a pre-existing fabric in the country rock, a sill is an example of a concordant tabular intrusive body. A discordant body is one that does cross pre-existing fabrics in the country rock, a dike is an example of a discordant tabular body.

A non-tabular intrusive body is further classified by shape and size. Stock is a term that is used for a non-tabular body that is exposed for less than 100 km2, and batholith is used to describe anything exposed for larger than 100 km2. This size classification does not take into account the true size of the body, which is why some ambiguity in the use of pluton came about. A non-tabular body can also be classified based on shape, if the bottom of the body is parallel with the underlying country rock then it is termed a laccolith. If the bottom of the body is a basin and the top of the body is flat then it is a lopolith. A laccolith is thought to be formed when more siliceous and thus more viscous magma is intruded. The horizontal movement of the magma is limited by the viscosity, which leads to the magma pushing the rock above it up creating a dome shape. Lopoliths are believed to have a more mafic, and therefore less viscous, source. Lopoliths tend to be larger than laccoliths, and are believed to get their lenticular shape from the weight of the intruding magma compressing the underlying country rock, or the shape comes from the evacuation of a magma chamber below the intruding magma, causing the country rock to collapse and creating a basin. Some of these terms might be outdated, and not accurately describe the shape of a pluton but they are still commonly used.[2]

Formation

Plutons are believed to be formed from either one single magmatic event, or several incremental events. Recent evidence suggests the incremental formation model is more likely. While there is little visual evidence of multiple injections in the field, there is geochemical evidence.[3] Zircon zoning is a key part to determining if a single magmatic event or a series of injections were the methods of emplacement. Another side of the incremental theory is that plutons formed from the amalgamation of small intrusions.[4] The incremental model suggests that there is more time in-between injections to account for the fractional crystallization that allows the newest injection to go in to the least crystallized part of the body.

See also

References

- ^ Winter, John D (2010). Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. United States of America: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 67–79. ISBN 978-0-32-159257-6.

- ^ Cawthorn, R.G. (September 2018). "Lopolith – A 100 year-old term. Is it still definitive?". South African Journal of Geology. 121 (3): 253–260. doi:10.25131/sajg.121.0019.

- ^ Miller, Calvin (March 2011). "Growth of plutons by incremental emplacement of sheets in crystal-rich host: Evidence from Miocene intrusions of the Colorado River region, Nevada, USA". Tectonophysics. 500, 1–4 (1): 65–77. Bibcode:2011Tectp.500...65M. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2009.07.011.

- ^ Glazner, Allen (May 2004). "Are plutons assembled over millions of years by amalgamation from small magma chambers?" (PDF). GSA Today. 14 4/5: 4–11.

- Glazner, A. F., Bartley, J. M., Coleman, D. S., Gray, W. and Taylor, R. Z. (2004). "Are plutons assembled over millions of years by amalgamation from small magma chambers?" GSA Today, 14 (4: April), pp. 4–11.

- Young, Davis A. (2003). Mind Over Magma: the Story of Igneous Petrology. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-10279-1.

Further reading

- Best, Myron G. (1982). Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman & Company. pp. 119 ff. ISBN 0-7167-1335-7.