Qualitative geography

Qualitative geography is a subfield and methodological approach to geography focusing on nominal data, descriptive information, and the subjective and interpretive aspects of how humans experience and perceive the world.[2][1] Often, it is concerned with understanding the lived experiences of individuals and groups and the social, cultural, and political contexts in which those experiences occur. Thus, qualitative geography is traditionally placed under the branch of human geography; however, technical geographers are increasingly directing their methods toward interpreting, visualizing, and understanding qualitative datasets, and physical geographers employ nominal qualitative data as well as quanitative.[3][1] Furthermore, there is increased interest in applying approaches and methods that are generally viewed as more qualitative in nature to physical geography, such as in critical physical geography.[4] While qualitative geography is often viewed as the opposite of quantitative geography, the two sets of techniques are increasingly used to complement each other.[2][5][4] Qualitative research can be employed in the scientific process to start the observation process, determine variables to include in research, validate results, and contextualize the results of quantitative research through mixed-methods approaches.[3][5][6][7][8]

Approaches[edit]

Several scientific fields/subfields created or modified and applied specific concepts, theories, methods, principles/laws, techniques/technologies, etc. so to propose specific interdisciplinary approaches for addressing qualitative research-questions of geography.[citation needed] Qualitative geography is the interdisciplinary field of geography gathering these proposed interdisciplinary-approaches from:

Concept of place[edit]

Geography considers place as one of its most significant and complicated concepts, and describing a place is something that qualitative methods are absolutely necessary to accomplish.[9][10][11][12] When referring to human geography, place is a combination of the geographical coordinates of a location, the activities that take place there (past, present, and future), and the interpretations that human individuals and groups assigned to that space. This can be highly intricate because people may have different uses and perceptions of the exact location at different times. Moreover, places are not isolated entities and have complex spatial connections, as geography is interested in how an area is positioned relative to all other locations.[13][14] Therefore, geography includes all spatial phenomena at a particular site, the various meanings and uses attributed to it, and how it affects and is affected by all other locations on the planet.[11][12] While quantitative methods can describe spatial coordinates, the concept of place is, in many ways, non-quantifiable. Thus, while quantitative methods are incredibly useful in an understanding of space, qualitative methods are essential.

Methods[edit]

Qualitative geography is descriptive rather than numerical or statistical in nature.[6][15] Qualitative geography involves methods such as ethnography, interviews, and participant observation to gather data and make sense of the complexity and diversity of human geography.[2][8] It emphasizes the importance of subjectivity, reflexivity, and interpretation in research. Qualitative geography aims to produce rich, detailed accounts of the social and cultural landscapes in which people live. Qualitative research is often exploratory and descriptive, emphasizing the importance of subjectivity, reflexivity, and interpretation. While qualitative methods are often viewed as opposite to quantitative methods, there is an increased emphasis in geography on mixed methods approaches that employ both. Increasingly, technical geographers are exploring GIS methods applied to qualitative datasets.[6][3][16]

Qualitative cartography[edit]

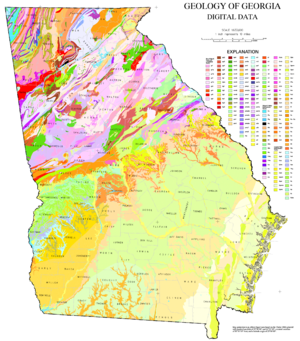

Qualitative cartography employs many of the same software and techniques as quantitative.[16] It may be employed to inform on map practices, or to visualize perspectives and ideas that are not strictly quantitative in nature.[16][6] Examples of common qualitative information mapped include Chorochromatic map of nominal data, such as land use and land cover.[1] In such cases, literature suggests using hue, rather than saturation, for displaying qualitative map topics.[1]

Qualitative cartography can be used as art to communicate concepts not necessarily tied to spatial coordinates or to demonstrate the impacts, limitations, and implications of cartography on diverse groups of people.[17]

Qualitative methods are employed by geographers seeking to improve cartographic practices by understanding how subjective cartographic choices impact how data is understood by users.[16]

Ethnography[edit]

Ethnographical research techniques are used by human geographers.[18] In cultural geography, there is a tradition of employing qualitative research techniques, also used in anthropology and sociology. Participant observation and in-depth interviews provide human geographers with qualitative data.

Interviews[edit]

Geographers can employ interviews to gather data and insights from individuals or groups about their experiences, perceptions, and opinions related to geographic phenomena.[8][19] Interviews can be conducted in various formats, including face-to-face, telephone, online, or written.[2][8] To employ interviews in research, geographers typically follow a structured or semi-structured format with questions or topics to guide the conversation.[8] These questions elicit specific information about the research topic while allowing participants to share their personal experiences and insights.[19] Geographers also often use open-ended questions to encourage participants to provide more detailed and nuanced responses.[8]

Geopoetics[edit]

Geopoetics is a discipline that combines geography and poetry to explore, contextualize, and communicate geographic concepts, research, and phenomena.[20] Geopoetics can be viewed as a methodology in itself, but is increasingly used as a mixed methods tool to explain the implications of quantitative geographic research and phenomena.[20][21] Topics addressed by geopoetics often include impacts of the anthropocene, such as climate change and environmental exploitation.[22][23][24][25][26]

Criticisms[edit]

One of the primary criticisms of qualitative geography is its lack of generalizability.[2][27] The findings of qualitative geography research are often based on small sample sizes, specific cases, or small-scale phenomena, making it challenging to generalize the results to larger populations or areas or capture larger patterns and trends. The data often rely on the research participants' unique circumstances and experiences, making qualitative research studies challenging to replicate. This makes strictly controlling variables, systematic data collection, and analysis procedures challenging. Finally, qualitative geographic research often relies heavily on the researcher's subjective interpretation of the data, which can introduce potential bias into the study. The researcher's background, experiences, and assumptions can influence their interpretation of the data. Ultimately, these factors of qualitative geographic lead some critics to argue that qualitative research lacks the rigor and objectivity of quantitative analysis. This can limit the applicability of the study to other researchers and policymakers.

Influential geographers[edit]

- Carl O. Sauer (1889–1975) – cultural geographer.

- David Harvey (born 1935) – Marxist geographer and author of theories on spatial and urban geography, winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Doreen Massey (1944–2016) – scholar in the space and places of globalization and its pluralities; winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Edward Soja (1940–2015) – worked on regional development, planning, and governance and coined the terms Synekism and Postmetropolis; winner of the Vautrin Lud Prize.

- Eric Magrane – Influential geographer in the geographic subfield of geopoetics.

- Mei-Po Kwan (born 1962) - geographer that coined the Uncertain geographic context problem and the neighborhood effect averaging problem.

- Nigel Thrift (born 1949) – originator of non-representational theory.

- Paul Vidal de La Blache (1845–1918) – founder of the French school of geopolitics, wrote the principles of human geography.

- Walter Christaller (1893–1969) – human geographer and inventor of Central place theory.

- Yi-Fu Tuan (1930-2022) – Chinese-American scholar credited with starting Humanistic Geography as a discipline.

Publications[edit]

Main category: Geography Journals

- Annals of the American Association of Geographers

- Antipode

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Dialogues in Human Geography

- Geographia Technica

- Geographical Review

- Geographical Bulletin

- GeoHumanities

- Journal of Rural Studies

- Journal of Maps

- National Geographic

- Progress in Human Geography

See also[edit]

- Arbia's law of geography

- Collaborative mapping

- Concepts and Techniques in Modern Geography

- Counter-mapping

- Geographic information systems in geospatial intelligence

- GIS and public health

- GIS Day

- GIS in archaeology

- Historical GIS

- Map communication model

- Methodological dualism

- Online qualitative research

- Participatory GIS

- Qualitative psychological research

- Quantitative history

- Scientific Geography Series

- Tobler's first law of geography

- Tobler's second law of geography

- Traditional knowledge GIS

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Brewer, Cynthia (1994). "Color use guidelines for mapping and visualization". In MacEachren, A.M.; Taylor, D.R. Fraser (eds.). Visualization in Modern Cartography. Elsevier. pp. 123–134. ISBN 1483287920. Retrieved 24 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e DeLyser, Dydia; Herbert, Steve; Aitken, Stuart; Crang, Mike; McDowell, Linda (November 2009). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Geography (1 ed.). SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781412919913. Retrieved 27 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Haidu, Ionel (2016). "What is Technical Geography – a letter from the editor". Geographia Technica. 11: 1–5. doi:10.21163/GT_2016.111.01.

- ^ a b Lave, Rebecca; Wilson, Matthew W.; Barron, Elizabeth S.; Biermann, Christine; Carey, Mark A.; Duvall, Chris S. (2013). "Viewpoint Intervention: Critical physical geography". Canadian Geographies. 58 (1). doi:10.1111/cag.12061. S2CID 8753111.

- ^ a b Diriwächter, R. & Valsiner, J. (January 2006) Qualitative Developmental Research Methods in Their Historical and Epistemological Contexts. FQS. Vol 7, No. 1, Art. 8

- ^ a b c d Burns, Ryan; Skupin, Andre´ (2013). "Towards Qualitative Geovisual Analytics: A Case Study Involving Places, People, and Mediated Experience". Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization. 48 (3): 157–176. doi:10.3138/carto.48.3.1691. S2CID 3269642. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Sale, Joanna E.M.; Thielke, Stephen (October 2018). "Qualitative research is a fundamental scientific process". Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 102: 129–133. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.04.024.

- ^ a b c d e f Dixon, C.; Leach, B. (1977). Questionnaires and Interviews in Geographical Research (PDF). Geo Abstracts. ISBN 0-902246-97-6.

- ^ Tuan, Yi-Fu (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (1 ed.). University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3877-2.

- ^ Tuan, Yi-Fu (1991). "A View of Geography". Geographical Review. 81 (1): 99–107. doi:10.2307/215179. JSTOR 215179. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ a b Castree, Noel (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, Connections and Boundaries in an Interdependent World (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 85–96. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ a b Gregory, Ken (2009). Key Concepts in Geography: Place, The Management of Sustainable Physical Environments (2 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. pp. 173–199. ISBN 978-1-4051-9146-3.

- ^ Tobler, Waldo (1970). "A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region" (PDF). Economic Geography. 46: 234–240. doi:10.2307/143141. JSTOR 143141. S2CID 34085823. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-08. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Tobler, Waldo (2004). "On the First Law of Geography: A Reply". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 94 (2): 304–310. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2004.09402009.x. S2CID 33201684. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Vibha, Pathak; Bijayini, Jena; Sanjay, Kaira (2013). "Qualitative research". Perspect Clin Res. 4 (3): 192. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.115389. PMC 3757586. PMID 24010063.

- ^ a b c d Suchan, Trudy; Brewer, Cynthia (2000). "Qualitative Methods for Research on Mapmaking and Map Use". The Professional Geographer. 52 (1): 145–154. doi:10.1111/0033-0124.00212. S2CID 129100721. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

- ^ Ribeiro, Daniel Melo (May 2018). "Art and cartography as a critique of borders". Proceedings of the ICA. 1: 1–6. doi:10.5194/ica-proc-1-95-2018. hdl:1843/43371.

- ^ Cook, Ian; Crang, Phil (1995). Doing Ethnographies.

- ^ a b Dixon, Chris; Leach, Bridget (1984). Survey Research in Underdeveloped Countries (PDF). ISBN 0-86094-135-3.

- ^ a b Magrane, Eric (2015). "Situating Geopoetics". GeoHumanities. 1 (1): 86–102. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2015.1071674. S2CID 219396902. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Magrane, Eric; Johnson, Maria (2017). "An art–science approach to bycatch in the Gulf of California shrimp trawling fishery". Cultural Geographies. 24 (3): 487–495. doi:10.1177/1474474016684129. S2CID 149158790. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Magrane, Eric (2021). "Climate geopoetics (the earth is a composted poem)". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11 (1): 8–22. doi:10.1177/2043820620908390. S2CID 213112503. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Nassar, Aya (2021). "Geopoetics: Storytelling against mastery". Dialogues in Human Geography. 1: 27–30. doi:10.1177/2043820620986397. S2CID 232162263.

- ^ Engelmann, Sasha (2021). "Geopoetics: On organising, mourning, and the incalculable". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11: 31–35. doi:10.1177/2043820620986398. S2CID 232162320. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Acker, Maleea (2021). "Gesturing toward the common and the desperation: Climate geopoetics' potential". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11 (1): 23–26. doi:10.1177/2043820620986396. S2CID 232162312. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Cresswell, Tim (2021). "Beyond geopoetics: For hybrid texts". Dialogues in Human Geography. 11: 36–39. doi:10.1177/2043820620986399. hdl:20.500.11820/b64b3dd4-c959-4a8e-877f-85d3058ce4b1. S2CID 232162314.

- ^ Fotheringham, A. Stewart; Brunsdon, Chris; Charlton, Martin (2000). Quantitative Geography: Perspectives on Spatial Data Analysis. Sage Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-5948-9.