Raja

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

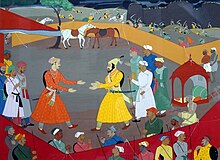

Raja (/ˈrɑːdʒɑː/; also spelled rajah, from Sanskrit राजन् rājan-), is a title for a monarch or princely ruler in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

The female form Rani (or Ranee, Rajin) applies equally to the wife of a Raja (or of an equivalent style such as Rana), usually as queen consort and occasionally as regent.[citation needed]

The title has a long history in the Indian subcontinent and South East Asia, being attested from the Rigveda, where a rājan- is a ruler, see for example the dāśarājñá, the "Battle of Ten Kings".

Etymology

Sanskrit rājan- is cognate to Latin rēx (genitive rēgis) 'king' (as in pre-republican Rome), Gaulish rīx, Gaelic rí (genitive ríg), etc., originally denoting heads of petty kingdoms and city states. It is believed to be ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European *h3rēǵs, a vrddhi formation to the root *h3reǵ- "to straighten, to order, to rule". The Sanskrit n-stem is secondary in the male title, apparently adapted from the female counterpart rājñī which also has an -n- suffix in related languages, compare Old Irish rígain and Latin regina. Cognates of the word rājan in other Indo-European languages include English reign and German Reich. The alternative English form 'rajah' is an example of the common error of inappropriately adding an 'h' to any final 'a', since masculine Sanskrit words ending in 'a' take the termination 'h' in the singular nominative case. It is to be deprecated, as being based on a false etymology.

Related titles and variations

Rather common, practically equivalent variants in Rajasthani, Marathi and Hindi, used as equivalent royal style in parts of India include Rana, Rao, Rai, Roy, Raol, Rawal and rawat (regional equivalents of Raja) and Yuv(a)raj(a/u) 'prince heir'.

Maharaja, or "great king", is literally a title for more significant rulers in India, but after some inflation of titles over time, there is no clear hierarchy between the terms. Hence during the British raj, precedence was rather determined by the gun salute.

Raja, Thakore and many variations, compounds and derivations including either of these were used in and around South Asia by most Hindu, and some Muslim, Buddhist, Jain and Sikh rulers, and still is commonly used in India, but Muslim princes rather used unrelated titles of Arabic/Persian origin like Nawab, Amir or Sultan.

- Raja රජ means King in Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri (රාජමන්ත්රී) is the Prince (රජ කුමරැ) lineage of King's generation in Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri title is aristocracy of the Kandiyan Kingdom මහනුවර in Sri Lanka.

Compound titles

- Badan Singh (d. 1756) was styled Raja Mahendra and founded the city and state Bharatpur, which his dynasty ruled as Maharajas.

- Raja Sahib was the royal style in Bansda (at least since 1701) until its upgrade from c.1829 to higher 'counterpart' Maharaja Sahib.

- Raja-i Rajgan was notably the royal style of :

- the former Rajas of J(h)ind from * until their 1911 upgrade to Maharaja.

- the former Rajas (originally Sardars) of Kapurthala from 1861 until their 1911 upgrade to Maharaja.

- two consecutive rulers of Patiala, the first of which was originally styled Maharaja, while the second 'upgraded back' to higher 'counterpart' Maharaja Rajgan.

- Raja Bahadur (literally 'higher then' Raja) :

- (perhaps from the start) and remained the rulers of Raigarh.

- as 1763 upgrade from the family title Raja Sar Desai in Maratha state Savantvadi.

Raja-ruled Indian states

| Princely state |

|---|

| Individual residencies |

| Agencies |

|

| Lists |

While most of the Hindu salute states were ruled by a Maharaja (or variation; some promoted from an earlier Raja- or equivalent style), even exclusively from 13 guns up, a number had Rajas :

- Hereditary salutes of 11-guns

- the Raja of Rajouri

- the Raja of Ali Rajpur

- the Raja of Bilaspur

- the Raja of Chamba

- the Raja of Faridkot

- the Raja of Jhabua

- the Raja of Mandi

- the Raja of Manipur

- the Raja of Narsinghgarh

- the Raja of Pudukkottai

- the Raja of Rajgarh

- the Raja of Sailana

- the Raja of Samthar

- the Raja of Sitamau

- the Raja of Suket

- Hereditary salutes of 9-guns (11-guns personal)

- Hereditary salute of 9-guns (11-guns local)

- the Raja of Savantwadi

- Hereditary salutes of 9-guns

- the Raja of Baraundha

- the Raja of Bhor

- the Raja of Chhota Udepur

- the Raja of Khilchipur

- the Raja of Maihar

- the Raja of Mudhol

- the Raja of Nagod(h)(e)

- the Raja of Sant

- the Raja of Shahpura

- Personal salute of 9-guns

- the Raja of Bashahr

There were many more Rajas (and variations) among the native rulers (of Chieftains) non-salute states, i.e. less prestigious princely states, often upgraded from a lower title and/or to a higher one (sometimes even becoming salute state), while less obvious shifts also occurred, including :

- Ajaygarh (Ajaigarh), from 1877 Sawai Maharaja; Hereditary salute of 11-guns

- Akalkot, invariable (even since 1708 founding as fief of Satara)

- Alirajpur(Ali Rajpur, since 1911, previously (equivalent) Rana; Hereditary salute of 11-guns

- Angul State in Orissa until 1948 British annexation

- Athgarh State

- Athmallik State (also until 1874 as a feudaotor jagir)

- etcetera

Raja is also frequently used as (confusing) rendering of other native regal titles, such as Swargadeo (Ahom language: Chao-Pha) of the Ahom Kingdom (alias Assam), where Charing Raja, Tipam Raja and Namrup Raja were the title for the first, second viz. third prince in line for succession.

There were many more Rajas (and variations) among the feudatory (e)states, such as jagirs.[citation needed]

Usage outside India

- In Pakistan, Raja is still used by Muslim Rajput clans as hereditary titles. Raja is also used as a given name by Hindus and Sikhs. Most notably Raja is used in Hazara division of Pakistan for the descendants of a Turkic dynasty. These Rajas ruled that part of Pakistan for decades and they still possess huge land in Hazara division of Pakistan and actively participate in the politics of the region.

- In Bangladesh, the royal families of indigenous people in the Chittagong Hill Tracts remain. Raja Debashish Roy is the current titular Raja of the Chakma Circle in Rangamati Hill District. His ancestor is Tridev Roy. Raja U Cho Prue Marma is the current titular Raja of the Bohmong Circle in Bandarban Hill District and Raja Saching Prue Chowdhury is the current titular Raja of the Mong Circle in Khagrachhari Hill District.

- In Sinhalese, the title 'Raja' means King of (part of Ceylon, now) Sri Lanka. Rajamanthri is the Prince lineage of King's generation especially Rajamanthri is aristocracy of the Kingdom of Kandy in Sri Lanka history.

- Indonesian has the word raja for "king". Leaders of local tribes and old Hindu kingdoms had that title before Indonesia became an independent nation. Various traditional princely states in Indonesia still style their ruler Raja, or did so until their abolition.

- In the Malay language, the word raja also means "king". In Malaysia, the ruler of the state of Perlis is titled the Raja of Perlis, which literally means the 'King of Perlis'. Most of the other state rulers are titled sultans. Nevertheless, the raja has an equal status with the other rulers and is one of the electors who designate one of their number as the Yang di-Pertuan Agong every five years. In the state of Perak, the title 'Raja' means 'Prince'. The White Rajahs (Raja Putih) of Sarawak in Borneo were James Brooke and his dynasty.

- In the Philippines, the title was used during the pre-colonial classical period to refer to sovereign kings (Rajahnate of Cebu, Rajahnate of Maynila, Rajahnate of Butuan). The Italian historian Antonio Pigafetta, in his account of the voyage of the first circumnavigation, recounted that when the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan reached the island-port of Limasawa/Mazaua in LeyteMindanao, on 28 March 1521, he was met by Raja Siaiu, the King of Mazaua. Later, he encountered Raja Colambu of the neighboring King of Butuan These are still on debate among historians. Magellan entered into the first recorded blood compact (cassi cassi - the Malay term used by Magellan) with Raja Siaiu. A few decades thereafter, when the Spanish fleet led by Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in the Philippine Archipelago, Rajah Tupas was ruling the Rajahnate of Cebu, and Rajah Sulaiman III and Rajah Matanda were in power in the Kingdom of Maynila.

- In Khmer, រជ្ជ (Reajjea) is used as a direct loanword from Sanskrit and by keeping its original meaning it is being used to indicate royalty when combined with other words.

Rajadharma

Rajadharma is the dharma which applies to the king, or the Raja. Dharma is that which upholds, supports, or maintains the order of the universe and is based on truth.[1] It is of central importance in achieving order and balance within the world and does this by demanding certain necessary behaviors from people.

The king served two main functions as the Raja: Secular and Religious.[2] The religious functions involved certain acts for propitiating gods, removing dangers, and guarding dharma, among other things. The secular functions involved helping prosperity (such as during times of famine), dealing out even-handed justice, and protecting people and their property. Once he helped the Vibhore to reach his goal by giving the devotion of his power in order to reduce the poverty from his kingdom.[2]

Protection of his subjects was seen as the first and foremost duty of the king. This was achieved by punishing internal aggression, such as thieves among his people, and meeting external aggression, such as attacks by foreign entities.[3] Moreover, the king possessed executive, judicial, and legislative dharmas, which he was responsible for carrying out. If he did so wisely, the king believed that he would be rewarded by reaching the pinnacle of the abode of the sun, or heaven.[4] However, if the king carried out his office poorly, he feared that he would suffer hell or be struck down by a deity.[5] As scholar Charles Drekmeier notes, "dharma stood above the king, and his failure to preserve it must accordingly have disastrous consequences". Because the king's power had to be employed subject to the requirements of the various castes' dharma, failure to "enforce the code" transferred guilt on to the ruler, and according to Drekmeier some texts went so far as to justify revolt against a ruler who abused his power or inadequately performed his dharma. In other words, Danda as both the king's tool of coercion and power, yet also his potential downfall, "was a two-edged sword".[6]

The executive duty of the king was primarily to carry out punishment, or danda.[7] For instance, a judge who would give an incorrect verdict out of passion, ignorance, or greed is not worthy of the office, and the king should punish him harshly.[8] Another executive dharma of the king is correcting the behavior of brahmanas that have strayed from their dharma, or duties, through the use of strict punishment.[9] These two examples demonstrated how the king was responsible for enforcing the dharmas of his subjects, but also was in charge of enforcing rulings in more civil disputes.[10] Such as if a man is able to repay a creditor but does not do so out of mean-spiritedness, the king should make him pay the money and take five percent for himself.[11]

The judicial duty of the king was deciding any disputes that arose in his kingdom and any conflicts that arose between dharmasastra and practices at the time or between dharmasastra and any secular transactions.[12] When he took the judgment seat, the king was to abandon all selfishness and be neutral to all things.[13] The king would hear cases such as thefts, and would use dharma to come to a decision.[14] He was also responsible for making sure that the witnesses were honest and truthful by way of testing them.[8] If the king conducted these trials according to dharma, he would be rewarded with wealth, fame, respect, and an eternal place in heaven, among other things.[15] However, not all cases fell upon the shoulders of the king. It was also the king's duty to appoint judges that would decide cases with the same integrity as the king.[16]

The king also had a legislative duty, which was utilized when he would enact different decrees, such as announcing a festival or a day of rest for the kingdom.[17]

Rajadharma largely portrayed the king as an administrator above all else.[18] The main purpose for the king executing punishment, or danda, was to ensure that all of his subjects were carrying out their own particular dharmas.[7] For this reason, rajadharma was often seen as the root of all dharma and was the highest goal.[19] The whole purpose of the king was to make everything and everyone prosper.[20] If they were not prospering, the king was not fulfilling his dharma.[21] He had to carry out his duties as laid down in the science of government and "not act at his sweet will."[18] Indeed, in the major writings on dharma (i.e. dharmasastra, etc.), the dharma of the king was regarded as the "capstone" of the other castes' dharma both due to the king's goal of securing the happiness and prosperity of his people[22] as well as his ability to act as the "guarantor" of the whole social structure through the enforcement of Danda (Hindu Punishment).[23]

In contemporary India, an idea pervades various levels of Hindu society: the "Ramrajya", or a kind of Hindu Golden Age in which through his strict adherence to rajadharma as outline in the Hindu epics and elsewhere, Rama serves as the ideal model of the perfect Hindu king. As Derrett put it, "everyone lives at peace" because "everyone knows his place" and could easily be forced into that place if necessary.[10] Ram's actions with regards to his wife Sita at the end of the Ramayana arguably serve as the best example of his utmost regard for his dharma as king, although other actions of his both before and after his defeat of Ravana are equally revered.

See also

Notes

- ^ Lariviere, 1989

- ^ a b Kane, p.101

- ^ Kane, p.56

- ^ Lariviere, p.19

- ^ Kane, p.96

- ^ Drekmeier, p.10

- ^ a b Kane, p.21

- ^ a b Lariviere, p.18

- ^ Lariviere, p.48

- ^ a b Derrett, p.598

- ^ Lariviere, p.67

- ^ Kane, p.9

- ^ Lariviere, p.10

- ^ Lariviere, p.8

- ^ Lariviere, p.9

- ^ Lariviere, p.20

- ^ Kane, p.98

- ^ a b Kane, p.31

- ^ Kane, p.3

- ^ Kane, p.11

- ^ Kane, p.62

- ^ Derret, p.599

- ^ Drekmeier, p.10-11

References

- Derrett, J.D.M. "Rajadharma." In The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Aug., 1976), pp. 597–609

- Drekmeier, Charles. Kingship and Community in Early India. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1962.

- Kane, Pandurang Vaman. 1968. History of Dharmaśāstra: (ancient and Mediæval Religious and Civil Law In India). [2d ed.] rev. and enl. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute.

- Lariviere, Richard W. 1989. "The Naradasmrti." University of Pennsylvania Studies on South Asia.