Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2015) |

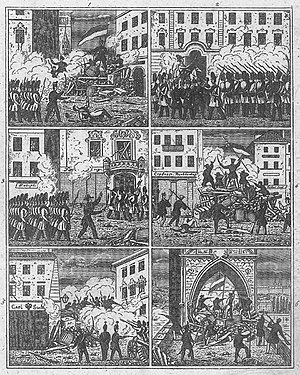

A set of revolutions took place in the Austrian Empire from March 1848 to November 1849. Much of the revolutionary activity had a nationalist character: the Empire, ruled from Vienna, included ethnic Germans, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Romanians, Croats, Venetians (Italians) and Serbs; all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Besides these nationalists, liberal and even socialist currents resisted the Empire's longstanding conservatism.

The early rumblings

The events of 1848 were the product of mounting social and political tensions after the Congress of Vienna of 1815. During the "pre-March" period, the already conservative Austrian Empire moved further away from ideas of the Age of Enlightenment, restricted freedom of the press, limited many university activities, and banning fraternities.

Social and political conflict

Conflicts between debtors and creditors in agricultural production as well as over land use rights in parts of Hungary (as in France) led to conflicts that occasionally erupted into violence. Conflict over organized religion was pervasive in pre-1848 Europe.[citation needed] Tension came both from within Catholicism and between members of different confessions. These conflicts were often mixed with conflict with the state. Important for the revolutionaries were state conflicts including the armed forces and collection of taxes. As 1848 approached, the revolutions the Empire crushed to maintain longstanding conservative minister Klemens Wenzel von Metternich's Concert of Europe left the empire nearly bankrupt and in continual need of soldiers.[citation needed] Draft commissions led to brawls between soldiers and civilians. All of this further agitated the peasantry, who resented their remaining feudal obligations.

Despite lack of freedom of the press and association, there was a flourishing liberal German culture among students and those educated either in Josephine schools[citation needed] or German universities. They published pamphlets and newspapers discussing education and language; a need for basic liberal reforms was assumed. These middle class liberals largely understood and accepted that forced labor is not efficient, and that the Empire should adopt a wage labor system. The question was of how to institute such reforms.

Notable liberal clubs of the time in Vienna included the Legal-Political Reading Club (established 1842) and Concordia Society (1840). They, like the Lower Austrian Manufacturers' Association (1840) were part of a culture that criticized Metternich's government from the city's coffeehouses, salons, and even stages, but prior to 1848 their demands had not even extended to constitutionalism or freedom of assembly, let alone republicanism. They had merely advocated relaxed censorship, freedom of religion, economic freedoms, and, above all, a more competent administration. They were outright opposed to popular sovereignty and the universal franchise.[1]

To their left was a radicalized, impoverished intelligentsia. Educational opportunities in 1840s Austria had far outstripped employment opportunities for the educated.[2]

Direct cause of the outbreak of violence

In 1846 there had been an uprising of Polish nobility in Austrian Galicia, which was only countered when peasants, in turn, rose up against the nobles.[3] The economic crisis of 1845-47 was marked by recession and food shortages throughout the continent. At the end of February 1848, demonstrations broke out in Paris. Louis-Philippe of France abdicated the throne, prompting similar revolts throughout the continent.

Revolution in the Austrian lands

An early victory leads to tension

After news broke of the February victories in Paris, uprisings occurred throughout Europe, including in Vienna, where the Diet (parliament) of Lower Austria in March demanded the resignation of Prince Metternich, the conservative State Chancellor and Foreign Minister. With no forces rallying to Metternich's defense, nor word from Ferdinand I of Austria to the contrary, he resigned on 13 March.[4] Metternich fled to London,[5] and Ferdinand appointed new, nominally liberal, ministers. By November, the Austrian Empire saw several short-lived liberal governments under five successive Ministers-President of Austria: Count Kolowrat (17 March–4 April), Count Ficquelmont (4 April–3 May), Baron Pillersdorf (3 May–8 July), Baron Doblhoff-Dier (8 July–18 July) and Baron Wessenberg (19 July–20 November).[6]

The established order collapsed rapidly because of the weakness of the Austrian armies. Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky was unable to keep his soldiers fighting Venetian and Milanese insurgents in Lombardy-Venetia, and had to, instead, order the remaining troops to evacuate.

Social and political conflict as well as inter and intra confessional hostility momentarily subsided as much of the continent rejoiced in the liberal victories. Mass political organizations and public participation in government became widespread.

However, liberal ministers were unable to establish central authority. Provisional governments in Venice and Milan quickly expressed desire to be part of an Italian confederacy of states; but for Venetian government this lasted five days only, after the 1848 armistice between Austria and Piedmont. A new Hungarian government in Pest announced its intentions to break away from the Empire and elect Ferdinand its King, and a Polish National Committee announced the same for the province of Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

Social and political tensions after the "Springtime of Peoples"

The victory of the party of movement was looked at as an opportunity for lower classes to renew old conflicts with greater anger and energy. Several tax boycotts and attempted murders of tax collectors occurred in Vienna. Assaults against soldiers were common, including against Radetzky's troops retreating from Milan. The archbishop of Vienna was forced to flee, and in Graz, the convent of the Jesuits was destroyed.

The demands of nationalism and its contradictions became apparent as new national governments began declaring power and unity. Charles Albert of Sardinia, King of Piedmont-Savoy, initiated a nationalist war on March 23 in the Austrian held northern Italian provinces that would consume the attention of the entire peninsula. The German nationalist movement faced the question of whether or not Austria should be included in the united German state, a quandary that divided the Frankfurt National Assembly. The liberal ministers in Vienna were willing to allow elections for the German National Assembly in some of the Habsburg lands, but it was undetermined which Habsburg territories would participate. Hungary and Galicia were clearly not German; German nationalists (who dominated the Bohemian Diet[7]) felt the old crown lands rightfully belonged to a united German state, despite the fact that the majority of the people of Bohemia and Moravia spoke Czech — a Slavic language. Czech nationalists viewed the language as far more significant, calling for a boycott of the Frankfurt Parliament elections in Bohemia, Moravia, and neighboring Austrian Silesia (also partly Czech-speaking). Tensions in Prague between German and Czech nationalists grew quickly between April and May.

By early summer, conservative regimes had been overthrown, new freedoms (including freedom of the press and freedom of association) had been introduced, and multiple nationalist claims had been exerted. New parliaments quickly held elections with broad franchise to create constituent assemblies, which would write new constitutions. The elections that were held produced unexpected results. The new voters, naïve and confused by their new political power, typically elected conservative or moderately liberal representatives. The radicals, the ones who supported the broadest franchise, lost under the system they advocated because they were not the locally influential and affluent men. The mixed results led to confrontations similar to the "June Days" uprising in Paris. Additionally, these constituent assemblies were charged with the impossible task of managing both the needs of the people of the state and determining what that state physically is at the same time. The Austrian Constituent Assembly was divided into a Czech faction, a German faction, and a Polish faction, and within each faction was the political left-right spectrum. Outside the Assembly, petitions, newspapers, mass demonstrations, and political clubs put pressure on their new governments and often expressed violently many of the debates that were occurring within the assembly itself.

The Czechs held a Pan-Slavic congress in Prague, primarily composed of Austroslavs who wanted greater freedom within the Empire, but their status as peasants and proletarians surrounded by a German middle class doomed their autonomy [citation needed]. They also disliked the prospect of annexation of Bohemia to a German Empire.

Counterrevolution

Insurgents quickly lost in street fighting to King Ferdinand's troops led by General Radetzky, prompting several liberal government ministers to resign in protest. Ferdinand, now restored to power in Vienna, appointed conservatives in their places. These actions were a considerable blow to the revolutionaries, and by August most of northern Italy was under Radetzky's control.

In Bohemia, the leaders of both the German and Czech nationalist movements were both constitutional monarchists, loyal to the Habsburg Emperor. Only a few days after the Emperor reconquered northern Italy, Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz took provocative measures in Prague to prompt street fighting. Once the barricades went up, he led Habsburg troops to crush the insurgents. After having taken back the city, he imposed martial law, ordered the Prague National Committee dissolved, and sent delegates to the "Pan-Slavic" Congress home. These events were applauded by German nationalists, who failed to understand that the Habsburg military would crush their own national movement as well.

Attention then turned to Hungary. War in Hungary again threatened imperial rule and prompted Emperor Ferdinand and his court to once more flee Vienna. Viennese radicals welcomed the arrival of Hungarian troops as the only force able to stand up against the court and ministry. The radicals took control of the city for only a short period of time. Windisch-Grätz led soldiers from Prussia to quickly defeat the insurgents. Windisch-Grätz restored imperial authority to the city. The reconquering of Vienna was seen as a defeat over German nationalism. At this point, Ferdinand I named the noble Prince Felix zu Schwarzenberg head of government. Schwarzenberg, a consummate statesman, persuaded the feeble-minded Ferdinand to abdicate the throne to his 18-year-old nephew, Franz Joseph. Parliamentarians continued to debate, but had no authority on state policy.

Both the Czech and Italian revolutions were defeated by the Habsburgs. Prague was the first victory of counter-revolution in the Austrian Empire.

Lombardy-Venetia was quickly brought back under Austrian rule in the mainland, even because popular support for the revolution vanished: revolutionary ideals were often limited to part of middle and upper classes, which failed both to gain "hearts and minds" of lower classes and to convince the population about Italian nationalism. Most part of lower classes indeed were quite indifferent, and actually most part of Lombard and Venetian troops remained loyal.[8] The only widespread support to the revolution was in the cities of Milan and Venice, with the Republic of San Marco lasting under siege until 28th of August, 1849.

Revolution in the Kingdom of Hungary

The Hungarian Diet was reconvened in 1825 to handle financial needs. A liberal party emerged in the Diet. The party focused on providing for the peasantry in mostly symbolic ways because of their inability to understand the needs of the laborers. Lajos Kossuth emerged as the leader of the lower gentry in the Diet.

In 1848, news of the outbreak of revolution in Paris arrived as a new national cabinet took power under Kossuth, and the Diet approved a sweeping reform package, referred to as the "April laws" (also "March laws"), that changed almost every aspect of Hungary's economic, social, and political life:

- they gave the Magyar nobility and lower gentry in the parliament control over its own military, its budget, and foreign policy

- essentially created an autonomous national kingdom of Hungary with the Habsburg Emperor as its king

- demanded that the Hungarian government receive and expend all taxes raised in Hungary and have authority over Hungarian regiments in the Habsburg army

- ended the special status of Transylvania and Croatia-Slavonia.

These demands were not easy for the imperial court to accept, however, its weak position provided little choice. One of the first tasks of the Diet was abolishing serfdom, which they did rather quickly.

The Hungarian government set limits on the political activity of both the Croatian and Romanian national movements. Croats and Romanians had their own desires for self-rule and saw no benefit in replacing one central government for another. Armed clashes between the Hungarians and the Croats, Romanians, Serbs, along one border and Slovaks on the other ensued. In some cases, this was a continuation and an escalation of previous tensions, such as the 1845 July victims in Croatia.

The Habsburg Kingdom of Croatia and the Kingdom of Slavonia severed relations with the new Hungarian government in Pest and devoted itself to the imperial cause. Conservative Josip Jelačić, who was appointed the new ban of Croatia-Slavonia in March by the imperial court, was removed from his position by the constitutional monarchist Hungarian government. He refused to give up his authority in the name of the monarch. Thus, there were two governments in Hungary issuing contradictory orders in the name of Ferdinand von Habsburg.[9]

Aware that they were on the path to civil war in mid-1848, the Hungarian government ministers attempted to gain Habsburg support against Jelačić by offering to send troops to northern Italy. Additionally, they attempted to come to terms with Jelačić himself, but he insisted on the recentralization of Habsburg authority as a pre-condition to any talks. By the end of August, the imperial government in Vienna officially ordered the Hungarian government in Pest to end plans for a Hungarian army. Jelačić then took military action against the Hungarian government without any official order.

The national assembly of the Serbs in Austrian Empire was held between 1 and 3 May 1848 in Sremski Karlovci, during which the Serbs proclaimed autonomous Habsburg crownland of Serbian Vojvodina. The war started, leading to clashes as such in Srbobran, where on July 14, 1848, the first siege of the town by Hungarian forces began under Baron Fülöp Berchtold. The army was forced to retreat due to a strong Serbian defense. With war raging on three fronts (against Romanians and Serbs in Banat and Bačka, and Romanians in Transylvania), Hungarian radicals in Pest saw this as an opportunity. Parliament made concessions to the radicals in September rather than let the events erupt into violent confrontations. Shortly thereafter, the final break between Vienna and Pest occurred when Field Marshal Count Franz Philipp von Lamberg was given control of all armies in Hungary (including Jelačić's). In response to Lamberg being attacked on arrival in Hungary a few days later, the imperial court ordered the Hungarian parliament and government dissolved. Jelačić was appointed to take Lamberg's place. War between Austria and Hungary had officially begun.

The war led to the October Crisis in Vienna, when insurgents attacked a garrison on its way to Hungary to support Croatian forces under Jelačić. After Vienna was recaptured by imperial forces, General Windischgrätz and 70,000 troops were sent to Hungary to crush the Hungarian revolution and as they advanced the Hungarian government evacuated Pest. However the Austrian army had to retreat after heavy defeats in the Spring Campaign of the Hungarian Army from March to May 1849. Instead of pursuing the Austrian army, the Hungarians stopped to retake the Fort of Buda and prepared defenses. In June 1849 Russian and Austrian troops entered Hungary heavily outnumbering the Hungarian army. Kossuth abdicated on August 11, 1849 in favour of Artúr Görgey, who he thought was the only general who was capable of saving the nation. However, in May 1849, Czar Nicholas I pledged to redouble his efforts against the Hungarian Government. He and Emperor Franz Joseph started to regather and rearm an army to be commanded by Anton Vogl, the Austrian lieutenant-field-marshal.[10] The Czar was also preparing to send 30,000 Russian soldiers back over the Eastern Carpathian Mountains from Poland. On August 13, after several bitter defeats in a hopeless situation Görgey, signed a surrender at Világos (now Şiria, Romania) to the Russians, who handed the army over to the Austrians.[11]

Slovak Uprising

Slovak Uprising was an uprising of Slovaks against Magyar (i.e. ethnic Hungarian) domination in Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia), within the 1848/49 revolution in the Habsburg Monarchy. It lasted from September 1848 to November 1849. During this period Slovak patriots established the Slovak National Council as their political representation and military units known as the Slovak Volunteer Corps. The political, social and national requirements of the Slovak movement were declared in the document entitled “Demands of the Slovak Nation” from April 1848.

The Second Wave of Revolutions

Revolutionary movements of 1849 faced an additional challenge: to work together to defeat a common enemy. Previously, national identity allowed Habsburg forces to conquer revolutionary governments by playing them off one another. New democratic initiatives in Italy in the spring of 1848[when?] led to a renewed conflict with Austrian forces in the provinces of Lombardy and Venetia. At the very first anniversary of the first barricades in Vienna, German and Czech democrats in Bohemia agreed to put mutual hostilities aside and work together on revolutionary planning. Hungarians faced the greatest challenge of overcoming the divisions of the previous year, as the fighting there had been the most bitter. Despite this, the Hungarian government hired a new commander and attempted to unite with Romanian democrat Avram Iancu, who was known as Crăişorul Munţilor ("The Prince of the Mountains"). However, division and mistrust were too severe.

Three days after the start of hostilities in Italy, Carlo Alberto abdicated the throne, essentially ending the Piedmontese return to war. Renewed military conflicts cost the Empire the little that remained of its finances. Another challenge to Habsburg authority came from Germany and the question of either "big Germany" (united Germany led by Austria) or "little Germany" (united Germany led by Prussia). The Frankfurt National Assembly proposed a constitution with Friedrich Wilhelhm of Prussia as monarch of a united federal Germany composed of only 'German' lands. This would have led to the relationship between Austria and Hungary (as a 'non-German' area) being reduced to a personal union under the Habsburgs, rather than a united state, an unacceptable arrangement for both the Habsburgs and Austro-German liberals in Austria. In the end, Friedrich Wilhelm refused to accept the constitution written by the Assembly. Schwarzenberg dissolved the Hungarian Parliament in 1849, imposing his own constitution that conceded nothing to the liberal movement. Appointing Alexander Bach head of internal affairs, he oversaw the creation of the Bach system, which rooted out political dissent and contained liberals within Austria and quickly returned the status quo. After the deportation of Lajos Kossuth, a nationalist Hungarian leader, Schwarzenberg faced uprisings by Hungarians. Playing on the long-standing Russian tradition of conservativism, he convinced tsar Nicholas I to send Russian forces in. The Russian army quickly destroyed the rebellion, forcing the Hungarians back under Austrian control. In less than three years, Schwarzenberg had returned stability and control to Austria. However, Schwarzenberg had a stroke in 1852, and his successors failed to uphold the control Schwarzenberg had so successfully maintained.

See also

References

- Bidelux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16111-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sperber, Jonathan (2005). The European Revolutions, 1848-1851. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83907-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schwarzschild, Léopold (1947). The Red Prussian: The Life and Legend of Karl Marx. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, pp. 315–316

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, p. 316

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, pp. 295–296

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, p. 298

- ^ Schwarzschild 1947, p. 174: "Metternich, like Louis Philippe, fled to London"

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, p. 314

- ^ Bidelux & Jeffries 1998, p. 310

- ^ The Italians who stayed loyal to the Habsburgs, Gilberto Oneto, 8th December 2010

- ^ Sperber 2005, p. 143

- ^ Marx & Engels, p. 618.

- ^ Szabó, János B. (5 September 2006). "Hungary's War of Independence". historynet.com. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

Further reading

- Robin Okey, The Habsburg Monarchy c. 1765-1918: From Enlightenment to Eclipse, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002

- Otto Wenkstern, History of the war in Hungary in 1848 and 1849, London: J. W. Parker, 1859 (Digitized version)