Runamo

Runamo is a cracked dolerite dike that was for centuries held to be a runic inscription and gave rise to a famous scholarly controversy in the 19th century.[1] It is located 2.7 km from the church of Bräkne-Hoby in Blekinge, Sweden.[1]For hundreds of years people said it was possible to read an inscription, and learned men referred to it.[1]

As early as the 12th century, the Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus reported in the introduction to his Gesta Danorum that the runic inscription was no longer legible being too worn down. This had been established by a delegation sent by the Danish king Valdemar I of Denmark (1131–1182) to read the inscription:

Now in Bleking is to be seen a rock which travellers can visit, dotted with letters in a strange character. For there stretches from the southern sea into the desert of Vaarnsland a road of rock, contained between two lines a little way apart and very prolonged, between which is visible in the midst a level space, graven all over with characters made to be read. And though this lies so unevenly as sometimes to break through the tops of the hills, sometimes to pass along the valley bottoms, yet it can be discerned to preserve continuous traces of the characters. Now Waldemar, well-starred son of holy Canute, marvelled at these, and desired to know their purport, and sent men to go along the rock and gather with close search the series of the characters that were to be seen there; they were then to denote them with certain marks, using letters of similar shape. These men could not gather any sort of interpretation of them, because owing to the hollow space of the graving being partly smeared up with mud and partly worn by the feet of travellers in the trampling of the road, the long line that had been drawn became blurred.[2]

Later in book 7 of Gesta Danorum, Saxo explains that it was a memorial by the Danish king Harald Wartooth to his father's great deeds:

HARALD, being of great beauty and unusual size, and surpassing those of his age in strength and stature, received such favour from Odin (whose oracle was thought to have been the cause of his birth), that steel could not injure his perfect soundness. The result was, that shafts which wounded others were disabled from doing him any harm. Nor was the boon unrequited; for he is reported to have promised to Odin all the souls which his sword cast out of their bodies. He also had his father's deeds recorded for a memorial by craftsmen on a rock in Bleking, whereof I have made mention.[3]

In spite of Saxo's report that the inscription was illegible as early as the 12th century, the Danish physician and antiquary Ole Worm declared in the 17th century that he had managed to read four letters in the description: Lund.[4]

There was considerable interest in the inscription during the Gothicismus of the early 19th century.[5] The Swedish writer Esaias Tegnér referred to it in his unfinished poem on the giantess Gerðr and Axel who became bishop Absalon of Lund.[5]

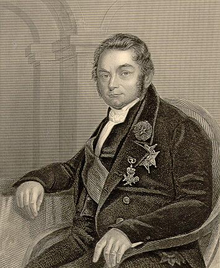

In 1833, the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters sent an expedition led by an Icelandic professor at the University of Copenhagen named Finnur Magnússon.[1][6] The mission was to explore the signs making use of geological and artistic expertise,[7] including the geologist Johan Georg Forchhammer.[1] At first, Finnur was unable to read the signs, but resolving to read them from right to left and by interpreting most of them as bind runes, he believed he discerned a poem.[8] This poem was an incantation by Harald Hildekinn (sic.), i.e. Harald Wartooth, for victory against the Swedish king Sigurd Ring at the Battle of Brávellir,[7] or stanzas from the skaldic poem that the champion Starkad composed on the battle.[1][6][9]

Finnur's report prompted the famous Swedish scientist Jöns Jacob Berzelius to undertake his own study in 1836, and he concluded that the inscription was nothing but natural cracks in the rock.[7] Finnur defended his thesis in an extensive publication in 1841, but the Danish archaeologist Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae made a third study at the location in 1844, which turned the general scholarly opinion towards Berzelius' theory.[6][7] Since then, it is generally considered to be a dolerite dike with cracks.[10]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f The article Runamo in Nordisk familjebok (1916).

- ^ The Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus, Preface, at the Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- ^ The Danish History of Saxo Grammaticus, book 7, at the Online Medieval and Classical Library.

- ^ An article in Sydöstran, retrieved January 1, 2006.

- ^ a b Andersson 1947:222

- ^ a b c Brate 1922:135

- ^ a b c d Andersson 1947:223

- ^ Magnusen 1841, pp 287-320

- ^ Jón Helgason, "Magnússon, Finnur", Dansk Biografisk Leksikon November 1938, volume 15, pp. 236-37. Template:Da icon

- ^ The article Runamo in Nationalencyklopedin.

Bibliography

- Andersson, Ingvar. (1947). Skånes historia, till Saxo och Skånelagen. P.A. Norstedt & söners förlag/Stockholm.

- Brate, Eric. (1922). Sveriges runinskrifter, online.

- Magnusen, Finn. (1841). Runamo og runerne. København.

- Saxo Grammaticus. Gesta Danorum, English Book I-IX: Online Medieval and Classical Library

- The article Runamo in Nationalencyklopedin (1995).

- The article Runamo in Nordisk familjebok (1916).