SMS Zähringen

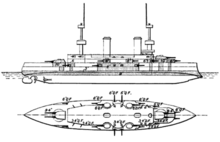

Painting of Zähringen in 1902

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Zähringen |

| Namesake | House of Zähringen |

| Builder | Germaniawerft, Kiel |

| Laid down | 21 November 1899 |

| Launched | 12 June 1901 |

| Commissioned | 25 October 1902 |

| Fate | Sunk as a blockship in 1945 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Template:Sclass- pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 12,798 t (12,596 long tons) |

| Length | 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) |

| Beam | 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) |

| Draft | 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts, triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) |

| Range | 5,000 nautical miles (9,300 km; 5,800 mi); 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

SMS Zähringen ("His Majesty's Ship Zähringen") was third ship of the Template:Sclass- of pre-dreadnought battleships of the German Imperial Navy. Laid down in 1899 at the Germaniawerft shipyard in Kiel, she was launched on 12 June 1901 and commissioned on 25 October 1902. Her sisters were Wittelsbach, Wettin, Schwaben and Mecklenburg; they were the first capital ships built under the Navy Law of 1898, brought about by Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz.

Zähringen saw active duty in the I Squadron of the German fleet for the majority of her career. The ship was rapidly superseded by new "all-big-gun" warships, however, and as a result served for less than eight years before being decommissioned on 21 September 1910. After the start of World War I in August 1914, Zähringen was brought back to active duty in the IV Battle Squadron. The ship saw limited duty in the Baltic Sea against Russian forces, though the threat from British submarines forced the ship to withdraw by 1916.

Zähringen was converted into a target ship in 1917 for the remainder of the war. In the mid-1920s, Zähringen was heavily reconstructed and equipped for use as a radio-controlled target ship. She served in this capacity until 1944, when she was sunk in Gotenhafen by British bombers during World War II. The retreating Germans raised the ship and moved it to the harbor mouth where they scuttled it to block the port. Zähringen was broken up in situ in 1949–50.

Description

Zähringen was 126.8 m (416 ft 0 in) long overall and had a beam of 22.8 m (74 ft 10 in) and a draft of 7.95 m (26 ft 1 in) forward. The ship was powered by three 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion engines that drove three screws. Steam was provided by six naval and six cylindrical coal-fired boilers. Zähringen's powerplant was rated at 14,000 metric horsepower (13,808 ihp; 10,297 kW), which generated a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). She had a crew of 30 officers and 650 enlisted men.[1]

Zähringen's armament consisted of a main battery of four 24 cm (9.4 in) SK L/40 guns in twin gun turrets,[a] one fore and one aft of the central superstructure.[2] Her secondary armament consisted of eighteen 15 cm (5.9 inch) SK L/40 guns and twelve 8.8 cm (3.45 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns. The armament suite was rounded out with six 45 cm (18 in) torpedo tubes, all submerged in the hull; one was in the bow, one in the stern, and the other four were on the broadside. Her armored belt was 225 millimeters (8.9 in) thick in the central portion that protected her magazines and machinery spaces, and the deck was 50 mm (2.0 in) thick. The main battery turrets had 250 mm (9.8 in) of armor plating.[3]

Service history

Zähringen's keel was laid on 21 November 1899, at Friedrich Krupp's Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel.[4][5] She was ordered under the contract name "E", as a new unit for the fleet.[3] The Wittelsbach class was the first battleship class built under the terms of the Navy Law of 1898, the chief proponent of which was Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz.[6] Zähringen was launched on 12 June 1901, with her launching speech given by Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden and head of the House of Zähringen; his wife, Grand Duchess Louise, christened the ship.[4] Zähringen was commissioned on 25 October 1902,[7] and began her sea trials, which lasted until 10 February 1903. She thereafter replaced the battleship Brandenburg in the I Squadron of the Active Fleet.[4][8]

In 1905 the German fleet was reorganized into two squadrons of battleships. Zähringen was assigned to the I Division of I Squadron, alongside her sisters Wettin and Wittelsbach. The German fleet at that time consisted of another three-ship division in the I Squadron and 2 three-ship divisions in the II Squadron. This was supported by a reconnaissance division, composed of two armored cruisers and six protected cruisers.[9]

The Template:Sclass-s—the most powerful battleships yet built in Germany—were beginning to enter service by 1907. This provided the Navy with enough ships to form two full battle squadrons of eight ships each. The fleet was then renamed the Hochseeflotte (High Seas Fleet).[8] On 21 September 1910, Zähringen was decommissioned and her crew was transferred to the new dreadnought Rheinland, which had recently been completed.[10] In 1912, Zähringen and her sisters were recommissioned as the III Squadron of the High Seas Fleet to augment the forces available for the annual summer fleet maneuvers in the North Sea. The exercises began on 2 September and were conducted in the area between Wilhelmshaven, Helgoland, and Cuxhaven.[11] While on maneuvers southwest of Helgoland on 14 September 1912, Zähringen accidentally rammed the torpedo boat G171. The torpedo boat was cut in half and quickly sank; six men drowned and a seventh died after being pulled from the sea.[12]

World War I

By 1914, Zähringen and her sisters were removed from active service and placed in the reserve squadron.[13] However, after the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Zähringen and the rest of her class were mobilized to serve in the IV Battle Squadron, under the command of Vice Admiral Ehrhard Schmidt.[14] Starting on 3 September, the IV Squadron, assisted by the armored cruiser Blücher, conducted a sweep into the Baltic. The operation lasted until 9 September and failed to bring Russian naval units to battle.[15] In May 1915, IV Squadron, including Zähringen, was transferred to support the German Army in the Baltic Sea area.[16] Zähringen and her sisters were then based in Kiel.

On 6 May, the IV Squadron ships were tasked with providing support to the assault on Libau. Zähringen and the other ships stood off Gotland in order to intercept any Russian cruisers that might try to intervene in the landings, which the Russians did not attempt. On 10 May, after the invasion force had entered Libau, the British submarines HMS E1 and HMS E9 spotted the IV Squadron, but were too far away to make an attack.[17] Zähringen and her sisters were not included in the German fleet that assaulted the Gulf of Riga in August 1915, due to the scarcity of escorts. The increasingly active British submarines forced the Germans to employ more destroyers to protect the capital ships.[18]

By 1916, the increasing threat from British submarines in the Baltic convinced the German navy to withdraw the elderly Wittelsbach-class ships from active service.[19] Zähringen was initially used as a training ship in Kiel. In 1917, the ship was used to train stokers but then became a target ship.[7]

Reichsmarine and Kriegsmarine

As of April 1919, Zähringen lay in the harbor in Danzig; the ship had been decommissioned but retained its armament.[20] According to Article 181 of the Treaty of Versailles, Zähringen and her sisters were to be demilitarized.[21] This would permit the newly reorganized Reichsmarine to retain the vessels for auxiliary purposes.[2] Zähringen was therefore stricken from the navy list on 11 March 1920 and disarmed. She was then used as a hulk in Wilhelmshaven until 1926.[7]

In 1927–28, the Reichsmarine rebuilt the ship as a radio-controlled target vessel. The ship had its engine system overhauled; the three-shaft arrangement was replaced by a pair of 3-cylinder, vertical triple expansion engines. These were supplied with steam by two naval oil-fired, water-tube boilers. The system was designed to be operated remotely via wireless telegraph. The new propulsion system provided a top speed of 13.5 knots (25.0 km/h; 15.5 mph). The superstructure was also cut down and the hull was filled with cork. When the conversion was completed, Zähringen displaced 11,800 metric tons (11,600 long tons). While not in use as a target, the ship was manned by a crew of 67.[7] She served as a target vessel for the Reichsmarine and then the Kriegsmarine, together with the old battleship Hessen.[22]

On 18 December 1944, the old ship was hit by bombs during an air raid on Gotenhafen and sank in shallow water.[22] She was temporarily refloated and towed to the harbor entrance, where she was scuttled to block the port on 26 March 1945. The wreck was broken up in situ starting in 1949; work lasted until 1950.[7]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ Gröner, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Hore, p. 67.

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand Röhr & Steinmetz, p. 126.

- ^ Ships: Germany, p. 978.

- ^ Herwig, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e Gröner, p. 17.

- ^ a b Herwig, p. 45.

- ^ The British and German Fleets, p. 335.

- ^ Staff, p. 30.

- ^ Professional Notes: Germany, p. 1636.

- ^ Professional Notes: Germany, p. 1637.

- ^ Effective Fighting Ships, p. 18.

- ^ Scheer, p. 15.

- ^ Halpern, p. 185.

- ^ Scheer, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Halpern, p. 192.

- ^ Halpern, p. 197.

- ^ Herwig, p. 168.

- ^ Situation of German Warships, p. 72.

- ^ Treaty of Versailles, Article 181.

- ^ a b Ciupa, pp. 106–107.

References

Books

- Ciupa, Heinz (1979). Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1939–45 (in German). Baden Erich Pabel. OCLC 561148977.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert; Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe (Volume 8) [The German Warships]. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ASIN B003VHSRKE.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Scheer, Reinhard (1920). Germany's High Seas Fleet in the World War. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 2765294.

- Staff, Gary (2010). German Battleships: 1914–1918. Vol. 1. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-467-1.

Journals

- "Effective Fighting Ships, Built and Building". War Gazetteer. New York: New York Evening Post: 18. 1914. OCLC 676717007.

- "Professional Notes: Germany". Proceedings. 38. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute: 1631–1638. 1912. ISSN 0041-798X.

- "Ships: Germany". Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. 14. Washington, D.C.: American Society of Naval Engineers: 971–979. 1902. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1902.tb01376.x. ISSN 0099-7056. OCLC 3227025.

- "Situation of German Warships in April, 1919". Information Concerning the U.S. Navy and Other Navies. 14. Washington, D.C.: Office of Naval Intelligence: 72–73. 1919. OCLC 649139426.

- "The British and German Fleets". The United Service. 7. New York: Lewis R. Hamersly & Co.: 328–340 1905. OCLC 4031674.

- Wittelsbach-class battleships

- World War I battleships of Germany

- World War II auxiliary ships of Germany

- World War II shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea

- 1901 ships

- Auxiliary ships of the Reichsmarine

- Auxiliary ships of the Kriegsmarine

- Ships built in Kiel

- Ships sunk by British aircraft

- Maritime incidents in December 1944

- Maritime incidents in March 1945