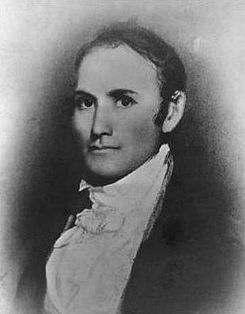

Solomon P. Sharp

Solomon P. Sharp | |

|---|---|

| |

| 5th Attorney General of Kentucky | |

| In office October 30, 1821 – 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Ben Hardin |

| Succeeded by | Frederick W. S. Grayson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1813 – March 3, 1817 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Desha |

| Succeeded by | David Walker |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 22, 1787 Abingdon, Virginia |

| Died | November 7, 1825 (aged 38) Frankfort, Kentucky |

| Resting place | Frankfort Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Eliza T. Scott |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | Kentucky militia |

| Years of service | 1812 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 |

Solomon Porcius Sharp (August 22, 1787 – November 7, 1825) was attorney general of Kentucky and a member of the United States Congress and the Kentucky General Assembly. His murder at the hands of Jereboam O. Beauchamp in 1825 is referred to as the Beauchamp–Sharp Tragedy or The Kentucky Tragedy.

Sharp began his political career representing Warren County, in the Kentucky House of Representatives. He briefly served in the War of 1812, then returned to Kentucky and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1813. He was re-elected to a second term, though his support of a controversial bill regarding legislator salaries cost him his seat in 1816. Aligning himself with Kentucky's Debt Relief Party, he returned to the Kentucky House in 1817 but resigned his seat in 1821 to accept Governor John Adair's appointment to the post of Attorney General of Kentucky. Adair's successor, Joseph Desha, re-appointed him to this position. In 1825, Sharp resigned as attorney general to return to the Kentucky House.

In 1818, rumors surfaced that Sharp had fathered a stillborn illegitimate child with Anna Cooke. Sharp denied the charge, and the immediate political effects were minimal. When the charges were repeated during Sharp's 1825 General Assembly campaign, he supposedly claimed that the child was a mulatto and could not have been his. Whether Sharp actually made such a claim, or whether it was a rumor started by his political enemies, remains in doubt. Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Cooke in 1824 and was incensed by this attack upon her honor, fatally stabbed Sharp in Sharp's home early on the morning of November 7, 1825. Sharp's murder became the inspiration for fictional works, most notably Edgar Allan Poe's unfinished play Politian and Robert Penn Warren's World Enough and Time.[1]

Personal life

Solomon Sharp was born on August 22, 1787, at Abingdon, Washington County, Virginia.[2] He was the fifth child and third son of Captain Thomas and Jean (Maxwell) Sharp.[2] Through the male line he was a great-great-grandson of John Sharp, Archbishop of York. Thomas Sharp was a veteran of the Revolutionary War, participating in the Battle of King's Mountain.[3] The family briefly moved to the area near Nashville, Tennessee, before settling permanently at Russellville, Logan County, Kentucky, sometime between 1798 and 1800.[3][4][5]

Little is known of Sharp's educational background; the schools of Logan County were primitive during his childhood years. Nevertheless, he studied law in some capacity, and was admitted to the bar sometime between 1806 and 1809. He opened a practice in Russellville, but soon relocated to Bowling Green where he engaged in land speculation, sometimes in partnership with his brother, Dr. Leander Sharp.[6]

On December 17, 1818, Sharp married Eliza T. Scott; the union produced three children. He moved the family to Frankfort, Kentucky, in 1820.[5] Months later, a woman named Anna Cooke claimed Sharp was the father of her stillborn illegitimate child; Sharp denied this claim.[7] Because of the child's dark skin tone, some speculated that the child was a mulatto.[7] The scandal soon abated, and although Sharp's political opponents would continue to call attention to it, his reputation remained largely untarnished.[8]

Political career

Sharp's first political office came in 1809, when he was elected to represent Warren County in the Kentucky House of Representatives.[5] During his tenure, he supported the election of Henry Clay to the U.S. Senate, the creation of a state lottery, and the creation of an academy in Barren County.[9] He served on a number of committees, and for a time, served as interim speaker of the house during the General Assembly's second session.[9] He was re-elected in 1810 and 1811.[5] During the 1811 session, he worked with Ben Hardin to secure passage of a bill discouraging the practice of dueling.[3] He also opposed a measure allowing harsher treatment of slaves.[9]

Sharp's political service was interrupted by the War of 1812. On September 18, 1812, he enlisted as a private in the Kentucky militia, serving under Lieutenant Colonel Young Ewing. Twelve days later, he was promoted to major and made a part of Ewing's staff. Ewing's unit was put under the command of general Samuel Hopkins during his ineffective expedition against the Shawnee. In total, the expedition lasted only forty-two days and never actually engaged the enemy. Sharp recognized the value of a record of military service in Kentucky politics, however, and he eventually was promoted to the rank of captain and later, colonel, although sources do not explain when or why this happened.[10][11]

U.S. Representative

In 1813, Sharp was elected to the Thirteenth Congress as a member of the United States House of Representatives.[10] Aligning himself with the War Hawks, he defended President James Madison's decision to lead the country into the war, and supported a proposal to offer 100 acres (0.156 sq mi; 0.405 km2) of land to any British deserters.[12] In a speech on April 8, 1813, he opposed indemnity for those defrauded in the Yazoo land scandal.[13] He allied himself with South Carolina's John C. Calhoun against the Second Bank of the United States.[13]

Sharp was re-elected to the Fourteenth Congress, during which he served as chairman of the Committee on Private Land Claims.[10] He supported the controversial Compensation Act of 1816 sponsored by fellow Kentuckian Richard Mentor Johnson.[14] The measure, which paid Congressmen a flat salary instead of paying them only for the days when they were in session, was unpopular with the voters of his district.[14] When the next congressional session opened in December 1816, Sharp reversed his position and voted to repeal the law, but the damage was already done; he lost his seat in the House in the next election.[14]

In 1817, Sharp was again elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives. During his term, he supported measures for internal improvements, but opposed the creation of a state health board and a proposal to open the state's vacant lands to the widows and orphans of soldiers killed in the War of 1812. Most notably, however, he supported the creation of forty new banks in the state, and proposed a tax on the branches of the Bank of the United States in Lexington and Louisville.[14]

Attorney general of Kentucky

In 1821, Sharp began a campaign for a seat in the Kentucky Senate. His opponent, John Upshaw Waring, was a notably violent and malicious man. Waring sent two threatening letters to Sharp, and on June 18, 1821, published a handbill attacking Sharp's character. Five days later, Sharp ceased campaigning for the senatorial seat and accepted the appointment of Governor John Adair to the position of attorney general of Kentucky. Sharp's nomination was unanimously confirmed on October 30, 1821.[15]

Sharp took office at a critical time Kentucky's history. Still reeling from the financial Panic of 1819, state politicians had split into two camps: those who supported legislation favorable to debtors (the Debt Relief Party) and those who favored the protection of creditors (typically called Anti-Reliefers.) Sharp had identified himself with the Relief Party, as had Governor Adair.[16]

In the 1824 presidential election, Sharp alienated some of his constituency by supporting his old House colleague John C. Calhoun instead of Kentucky's favorite son, Henry Clay. When it was clear that Calhoun's bid would fail, Sharp threw his support behind Andrew Jackson. He served as secretary of a meeting of Jackson supporters in Frankfort on October 2, 1824.[17]

Governor Adair's term expired in 1825, and he was succeeded by another Relief Party member, General Joseph Desha. Desha and Sharp had been colleagues in Congress, and Desha re-appointed Sharp as attorney general. The Relief faction in the legislature managed to pass several measures favorable to debtors, but the Kentucky Court of Appeals struck them down as unconstitutional. Unable to muster the votes to remove the hostile justices on the Court of Appeals, Relief partisans in the General Assembly passed legislation to abolish the entire court and create a new one, which Governor Desha promptly stocked with sympathetic judges. For a time, two courts claimed authority as Kentucky's court of last resort; this period was referred to as the Old Court-New Court controversy.[18]

Sharp's role in the Relief Party's plan to abolish the old court and replace it with a new, more favorable court is not explicitly known, but as the administration's chief legal counsel, it is assumed he was heavily involved. He personally issued the order for Old Court clerk Achilles Sneed to turn over his records to New Court clerk Francis P. Blair. He also lent a measure of legitimacy to the New Court by practicing as attorney general before the New Court to the exclusion of the Old Court.[19]

On May 11, 1825, Sharp was charged with welcoming the Marquis de Lafayette to Kentucky on behalf of the Desha administration. At a banquet in Lafayette's honor three days later, Sharp toasted the guest of honor: "The People: Liberty will always be safe in their holy keeping." Shortly following this event, Sharp resigned as attorney general, likely because Relief Party advocates felt he would be more useful in the General Assembly.[20]

The Anti-Relief partisans nominated former Senator John J. Crittenden for one of the two seats apportioned to Franklin County in the state House.[21] The Relief Party countered with Sharp and Lewis Sanders, a prominent area lawyer.[21] During the campaign, the charges of Sharp's illegitimate child resurfaced.[22] It was alleged that Sharp made the claim that the child was mulatto and could not have been his; whether Sharp actually made this claim may never be known for certain.[22] Despite the controversy, Sharp netted the most votes in the election, receiving 69 more than Crittenden, who captured the second seat.[22]

Assassination and aftermath

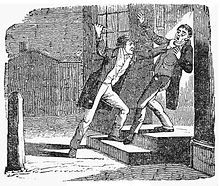

In the early hours of November 7, 1825, the day the General Assembly was to open its session, an assassin knocked on the door of Sharp's residence. When Sharp answered the door, the assassin grabbed him with his left hand and used his right to stab him in the heart with a poisoned dagger. Sharp died at approximately two o'clock in the morning. After lying in state in the House of Representatives Hall, he was buried in Frankfort Cemetery.[23]

Because of the timing of the assassination, speculation mounted that Sharp had been killed by an Anti-Relief partisan. Sharp's political rival, John J. Crittenden, attempted to blunt these accusations by personally introducing a resolution condemning the murder and offering a $3000 reward for the capture of the assassin.[24] The trustees of the city of Frankfort added a reward of $1000, and an additional $2000 reward was raised from private sources.[25][26] In the 1825 session of the General Assembly, a measure to form Sharp County from Muhlenberg County died on the floor due to the tumultuous politics of the session.[5]

In the investigation that followed, the evidence quickly pointed to Jereboam Beauchamp, who had married Anna Cooke in 1824, as the assassin. On November 11, 1825, a four-man posse arrested Beauchamp at his home in Franklin, Kentucky. He was tried and convicted of Sharp's murder on May 19, 1826. His sentence – execution by hanging – was to be carried out on June 16, 1826.[27] He requested a stay of execution so that he could write a justification of his actions. The request was granted, allowing Beauchamp to complete his book, The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp: who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. After two failed suicide attempts, Beauchamp was hanged for his crime on July 7, 1826.[28]

Beauchamp's Confession was published in 1826.[29] Some editions included The Letters of Ann Cook as an appendix, although historians dispute whether Cooke was actually their author.[29] The following year, Sharp's brother, Dr. Leander Sharp, wrote Vindication of the character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp to defend him from the charges contained in Beauchamp's confession.[29] In Vindication, Dr. Sharp portrayed the killing as a political assassination: he named Patrick Darby, a partisan of the Anti-Relief faction, as co-conspirator with Beauchamp, also an Anti-Relief stalwart.[30] Darby threatened to sue Sharp if he published his Vindication; Waring threatened to kill him.[30] Heeding these threats, Sharp did not publish his work; all extant manuscripts remained in his house, where they were discovered during a remodeling many years later.[30]

Notes

- ^ Whited, pp. 404–405

- ^ a b Cooke, Part I, p. 27

- ^ a b c Levin, p. 109

- ^ Allen, p. 256

- ^ a b c d e Mathias, 814

- ^ Cooke, Part I, pp. 27, 29

- ^ a b Cooke, Part I, p. 38

- ^ Cooke, Part I, p. 39

- ^ a b c Cooke, Part I, p. 30

- ^ a b c Congressional Bio

- ^ Cooke, Part I, p. 31

- ^ Cooke, Part I, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b Cooke, Part I, p. 33

- ^ a b c d Cooke, Part I, p. 34

- ^ Cooke, Part I, pp. 39–40

- ^ Cooke, Part II, pp. 121–125

- ^ Cooke, Part II, p. 126

- ^ Cooke, Part II, pp. 126–130

- ^ Cooke, Part II, pp. 130–131

- ^ Cooke, Part II, p. 134

- ^ a b Kirwan, p. 58

- ^ a b c Cooke, Part II, p. 135

- ^ Cooke, Part II, pp. 137–140

- ^ Kirwan, p. 60

- ^ L. Johnson, p. 48

- ^ Cooke, Part II, p. 140

- ^ L. Johnson, p. 49

- ^ Cooke, Part II, pp. 143–146

- ^ a b c Whited, p. 404

- ^ a b c Johnson, "New Light of Beauchamp's Confession"

References

- Allen, William B. (1872). A History of Kentucky: Embracing Gleanings, Reminiscences, Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Statistics, and Biographical Sketches of Pioneers, Soldiers, Jurists, Lawyers, Statesmen, Divines, Mechanics, Farmers, Merchants, and Other Leading Men, of All Occupations and Pursuits. Bradley & Gilbert. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- Cooke, J.W. (1998). "The Life and Death of Colonel Solomon P. Sharp Part 1: Uprightness and Inventions; Snares and Net". The Filson Club Quarterly. 72 (1): pp. 24–41.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cooke, J.W. (1998). "The Life and Death of Colonel Solomon P. Sharp Part 2: A Time to Weep and A Time to Mourn". The Filson Club Quarterly. 72 (2): pp.121–151.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Johnson, Fred M. (1993). "New Light on Beauchamp's Confession?". Border States Online. Retrieved 2008-02-06.

- Johnson, Lewis Franklin (1922). Famous Kentucky tragedies and trials; a collection of important and interesting tragedies and criminal trials which have taken place in Kentucky. The Baldwin Law Publishing Company. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- Kirwan, Albert Dennis (1974). John J. Crittenden: The Struggle for the Union. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0837169224.

- Levin, H. (1897). Lawyers and Lawmakers of Kentucky. Chicago, Illinois: Lewis Publishing Company. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Mathias, Frank F. (1992). Kleber, John E (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813117720.

- United States Congress. "Solomon P. Sharp (id: S000295)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Whited, Stephen R. (2002). "Kentucky Tragedy". In Joseph M. Flora and Lucinda Hardwick MacKethan (ed.). The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People. Associate Editor: Todd W. Taylor. LSU Press. ISBN 0807126926. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

Further reading

- Beauchamp, Jereboam O. (1826). The confession of Jereboam O. Beauchamp: who was hanged at Frankfort, Ky., on the 7th day of July, 1826, for the murder of Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Bruce, Dickson D. (2003). "The Kentucky Tragedy and the Transformation of Politics in the Early American Republic". The American Transcendental Quarterly. 17.

- Bruce, Dickson D. (2006). The Kentucky Tragedy: A Story of Conflict and Change in Antebellum America. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807131733.

- Coleman, John Winston (1950). The Beauchamp-Sharp tragedy; an episode of Kentucky history during the middle 1820's. Frankfort, Kentucky: Roberts Print. Co.

- St. Clair, Henry (1835). The United States Criminal Calendar. Charles Gaylord. Retrieved 2008-12-09.

- Schoenbachler, Matthew G. (2009). Murder & Madness: The Myth of the Kentucky Tragedy. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813125664.

- Sharp, Leander J. (1827). Vindication of the character of the late Col. Solomon P. Sharp. Frankfort, Kentucky: A. Kendall and company.

External links

- 1787 births

- 1825 deaths

- American prosecutors

- Assassinated American politicians

- Burials in Frankfort Cemetery

- Kentucky Attorneys General

- Kentucky lawyers

- Members of the Kentucky House of Representatives

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from Kentucky

- People from Abingdon, Virginia

- People murdered in Kentucky

- United States military personnel of the War of 1812