Songtsen Gampo

| Songtsän Gampo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emperor of Tibet | |||||

| |||||

| Predecessor | Namri Songtsen | ||||

| Successor | Mangsong Mangtsen | ||||

| Born | Songtsän between 557 and 617 Maizhokunggar, Tibet | ||||

| Died | 649 Zal-mo-sgang, 'phun-yul, Tibet (in modern Lhünzhub County) | ||||

| Burial | 651 smu-ri-smug-bo, Valley of the Kings, phying ba'ai | ||||

| Spouse | Pogong Mongza Tricham Bal-mo-bza' Khri-btsun (aka Bhrikuti, from Nepal) Gyasa Mung-chang (aka Princess Wencheng, from Tang China) Mi-nyag-bza' Zhyal-mo-btsun (from Tangut) Ri-thig-man (from Zhangzhung) | ||||

| Issue | Gungsong Gungtsen | ||||

| |||||

| Tibetan | |||||

| Wylie transliteration | Srong-btsan sGam-po | ||||

| THL | Songtsen Gampo | ||||

| Great Minister | |||||

| Father | Namri Löntsen | ||||

| Mother | Driza Tökarma | ||||

Template:Contains Tibetan text

| Part of a series on |

| Tibetan Buddhism |

|---|

|

Songtsen Gampo (Tibetan: སྲོང་བཙན་སྒམ་པོ, Wylie: srong btsan sgam po, 569–649?/605–649?) was the founder of the Tibetan Empire[a], and is traditionally credited with the introduction of Buddhism to Tibet, influenced by his Nepali and Chinese queens, as well as being the unifier of what were previously several Tibetan kingdoms.[1] He is also regarded as responsible for the creation of Tibetan alphabet and therefore the establishment of Classical Tibetan, the language spoken in his region at the time, as the literary language of Tibet.

His mother, the queen, is identified as Driza Tökarma (Wylie: 'bri bza thod dkar ma "the Bri Wife [named] White Skull Woman"). The dates of his birth and when he took the throne are not certain. In Tibetan accounts, it is generally accepted that he was born in an Ox year of the Tibetan calendar, which means one of the following dates: 557, 569, 581, 583, 605 or 617 CE.[2] He is thought to have ascended the throne at age thirteen (twelve by Western reckoning), by this reckoning c. 629.[1][3]

There are difficulties with this position, however, and several earlier dates for the birth of Songtsän Gampo have been suggested, including 569, 593 or 605.[4]

Early life and cultural background

It is said that Songtsän Gampo was born at Gyama in Meldro, a region to the northeast of modern Lhasa), the son of the Yarlung king Namri Songtsen. The book The Holder of the White Lotus says that it is believed that he was a manifestation of Avalokiteśvara, of whom the Dalai Lamas are similarly believed to be a manifestation.[5] His identification as a cakravartin and incarnation of Avalokiteśvara began in earnest in the indigenous Buddhist literary histories of the 11th century.[6]

Family

Some Dunhuang documents say that, as well as his sister Sad-mar-kar (or Sa-tha-ma-kar), Songtsän Gampo had a younger brother who was betrayed and died in a fire, sometime after 641. Apparently, according to one partially damaged scroll from Dunhuang, there was hostility between Sa-tha-ma-kar and Songtsän Gampo's younger brother, bTzan-srong, who, as a result, was forced to settle in gNyal (an old district to the southeast of Yarlung and across the 5,090 metres (16,700 ft) Yartö Tra Pass, which bordered on modern Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh in India). Little, if anything, else is known about this brother.[7][8]

Songtsän Gampo's mother, the queen, is identified as a member of the Tsépong clan Wylie: tshe spong, Tibetan Annals Wylie: tshes pong), which played an important part in the unification of Tibet. Her name is recorded variously but is identified as Driza Tökarma ("the Bri Wife [named] White Skull Woman", Wylie: bri bza' thod dkar ma, Tibetan Annals Wylie: bring ma tog dgos).[9]

Songtsän Gampo had six consorts, of whom four are considered "native" and two - the well-known ones - foreign.[10] Highest-ranking was Pogong Mongza Tricham (Wylie: pho gong mong bza' khri lcam, also called Mongza, "the Mong clan wife", who is said to have been the mother of Gungsong Gungtsen.[11] Other notable wives include a noble woman of the Western Xia known as Minyakza ("Western Xia wife", Wylie: mi nyag bza'),[12] and a noble woman from Zhangzhung. Well-known even today are his two 'foreign' wives: the Nepali princess Bhrikuti ("the great lady, the Nepalese wife", Wylie: bal mo bza' khri btsun ma) as well as the Chinese Princess Wencheng ("Chinese Wife", Wylie: rgya mo bza').[10] These two wives are credited in Tibetan tradition in playing crucial roles in the adoption of Buddhism in Tibet and held to explain the two great influences on Tibetan Buddhism, Indo-Nepali and Chinese.

Songtsän Gampo's heir, Gungsong Gungtsen, died before his father, so his son, Mangsong Mangtsen, took the throne. His mother is sometimes said to have been a Chinese princess (Wylie: kong jo) but this is thought to be highly unlikely. His mother was most probably Mangmoje Trikar (Wylie: mang mo rje khri skar),[13] who is mentioned in the Genealogy found in the hidden library in the caves in Dunhuang, the Tibetan Annals, which list the names of the Tibetan emperors and the names of their consorts who bore future emperors, and the clans they came from).[14]

Some accounts say that when Gungsong Gungtsen reached the age of thirteen (twelve by Western reckoning), his father, Songtsän Gampo, retired, and he ruled for five years (which could have been the period when Songtsän Gampo was working on the new constitution). Gungsong Gungtsen is also said to have married 'A-zha Mang-mo-rje when he was thirteen, and they had a son, Mangsong Mangtsen (r. 650-676 CE). Gungsong Gungtsen is said to have only ruled for five years when he died at eighteen. His father, Songtsän Gampo, took the throne again.[15] Gungsong Gungtsen is said to have been buried at Donkhorda, the site of the royal tombs, to the left of the tomb of his grandfather Namri Songtsen (gNam-ri Srong-btsan). The dates for these events are very unclear.[16][17][18] According to Tibetan tradition, Songstän Gampo was enthroned while still a minor as the thirty-third king of the Yarlung Dynasty after his father was poisoned circa 618.[19][20] He is said to have been born in an unspecified Ox year and was 13 years old (12 by Western reckoning) when he took the throne. This accords with the tradition that the Yarlung kings took the throne when they were 13, and supposedly old enough to ride a horse and rule the kingdom.[21] If these traditions are correct, he was probably born in the Ox year 605 CE. The Old Book of Tang notes that he "was still a minor when he succeeded to the throne."[19][22]

Cultural activities

Songtsän Gampo is said to have sent his minister Thonmi Sambhota to India to devise a script for Classical Tibetan, which led to the creation of the first Tibetan literary works and translations, court records and a constitution.[23] After Thonmi Sambhota returned from India,Songtsen Gampo stayed in a cave for three years with Thonmi Sambhota to learn whatever he had learned in India.

Songtsän Gampo moved the seat of his newly unified kingdom from the Yarlung Valley to Lhasa.[24]

He is also credited with bringing many new cultural and technological advances to Tibet. The Jiu Tangshu, or Old Book of Tang, states that after the defeat in 648 of an Indian army in support of Chinese envoys, the Chinese Emperor, Gaozong, a devout Buddhist, gave him the title variously written Binwang, "Guest King" or Zongwang, "Cloth-tribute King" and 3,000 rolls of multicoloured silk in 649[25] and granted the Tibetan king's request for "silkworms' eggs, mortars and presses for making wine, and workmen to manufacture paper and ink."[26]

Traditional accounts say that, during the reign of Songtsän Gampo, examples of handicrafts and astrological systems were imported from China and the Western Xia; the dharma and the art of writing came from India; material wealth and treasures from the Nepalis and the lands of the Mongols, while model laws and administration were imported from the Uyghurs of the Turkic Khaganate to the North.[27]

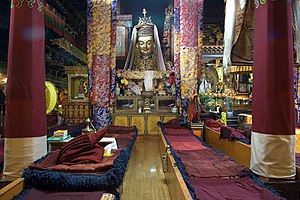

Introduction of Buddhism

Songtsän Gampo is traditionally credited with being the first to bring Buddhism to the Tibetan people. He is also said to have built many Buddhist temples, including the Jokhang in Lhasa, the city in which he is credited in one tradition with founding and establishing as his capital,[28][29] and Tradruk Temple in Nêdong. During his reign, the translation of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into Tibetan began.[30]

Songtsän Gampo is considered to be the first of the three Dharma Kings (Wylie: chos rgyal) — Songtsän Gampo, Trisong Detsen, and Ralpacan — who established Buddhism in Tibet.

The inscription on the Skar cung Pillar (erected by Ralpacan, who ruled c. 800-815) reports that during Songtsän Gampo's reign, "shrines of the Three Jewels were established by building the temple of Ra-sa [Lhasa] and so on."[31] The first edict of Trisong Detsen mentions a community of monks at this vihara.[32]

620s

Songtsän Gampo was adept at diplomacy as well as on the field of battle. The king's minister, Nyang Mangpoje Shangnang, with the aid of troops from Zhangzhung, defeated the Sumpa in northeastern Tibet circa 627 (Tibetan Annals [OTA] l. 2).

630s

Six years later (c. 632/633), Myang Mang-po-rje Zhang-shang was accused of treason and executed (OTA l. 4-5, Richardson 1965). Minister Mgar-srong-rtsan succeeded him.

The Jiu Tangshu records that the first ever embassy from Tibet arrived in China from Songtsän Gampo in the 8th Zhenguan year, or 634 CE.[33] Tang dynasty chronicles describe this as a tribute mission, but it brought an ultimatum demanding a marriage alliance, not subservient rituals. After this demand was refused, Tibet launched victorious military attacks against Tang affiliates in 637 and 638.[34]

The conquest of Zhang Zhung

There is some confusion as to whether Central Tibet conquered Zhangzhung during the reign of Songtsän Gampo or in the reign of Trisong Detsen (r. 755 until 797 or 804 CE).[35] The Old Book of Tang do seems to place these events clearly in the reign of Songtsän Gampo, for they say that in 634, Yangtong (Zhangzhung) and various Qiang peoples "altogether submitted to him." Following this, he united with the country of Yangtong to defeat the 'Azha, or Tuyuhun, and then conquered two more tribes of Qiang before threatening Songzhou with an army of (according to the Chinese) more than 200,000 men (100,000 according to Tibetan sources).[36] He then sent an envoy with gifts of gold and silk to the Chinese emperor to ask for a Chinese princess in marriage and, when refused, attacked Songzhou. According to the Tang annals, he finally retreated and apologised, and, later, the emperor granted his request,[37][38] but the histories written in Tibet all say that the Tibetan army defeated the Chinese and that the Tang emperor delivered a bride under threat of force.[36]

Early Tibetan accounts say that the Tibetan king and the king of Zhangzhung had married each other's sisters in a political alliance. However, the Tibetan wife of the king of the Zhangzhung complained of poor treatment by the king's principal wife. War ensued, and, through the treachery of the Tibetan princess, "King Ligmikya of Zhangzhung, while on his way to Sum-ba (Amdo province) was ambushed and killed by King Srongtsen Gampo's soldiers. As a consequence, The Zhangzhung kingdom was annexed to Bod [Central Tibet]. Thereafter the new kingdom born of the unification of Zhangzhung and Bod was known as Bod rGyal-khab."[39][40][41] R. A. Stein places the conquest of Zhangzhung in 645.[42]

Further campaigns

He next attacked and defeated the Tangut people who later formed the Western Xia state in 942 CE), the Bailang, and Qiang tribes.[43][44] The Bailan people were bounded on the east by the Tanguts and on the west by the Domi. They had been subject to the Chinese since 624.[45]

After a successful campaign against China in the frontier province of Songzhou in 635–36 (OTA l. 607),[46] the Chinese emperor agreed to send a Chinese princess for Songtsän Gampo to marry.

Around 639, after Songtsän Gampo had a dispute with his younger brother Tsensong (Wylie: brtsan srong), the younger brother was burnt to death by his own minister, Khasek (Wylie: mkha' sregs), possibly at the behest of the emperor.[47][48]

640s

The Old Book of Tang records that when the king of 泥婆羅, Nipoluo ("Nepal"),[49] the father of Licchavi king Naling Deva (or Narendradeva), died, an uncle, Yu.sna kug.ti, Vishnagupta) usurped the throne.[50] "The Tibetans gave him refuge and reestablished him on his throne [in 641]; that is how he became subject to Tibet."[22][51][52]

Sometime later, but still within the Zhenguan period (627-650 CE), the Tibetans sent an envoy to present day Nepal, where the king received him "joyfully", and, later, when a Tibetan mission was attacked in present-day India by then minister of emperor Harshavardhan who had usurped the throne after emperor Harshavardhan's death around 647 AD,[53] the Licchavi king came to their aid.[54] Songtsän Gampo married Princess Bhrikuti, the daughter of King Licchavi.

The Chinese Princess Wencheng, niece of the Emperor Taizong of Tang, left China in 640 to marry Songtsän Gampo, arriving the next year. Peace between China and Tibet prevailed for the remainder of Songtsän Gampo's reign.

Both wives are considered to have been incarnations of Tara (Template:Lang-bo), the Goddess of Compassion, the female aspect of Chenrezig:

- "Dolma, or Drolma (Sanskrit Tara). The two wives of Emperor Srong-btsan gambo are venerated under this name. The Chinese princess is called Dol-kar, of 'the white Dolma,' and the Nepalese princess Dol-jang, or 'the green Dolma.' The latter is prayed to by women for fecundity."[55]

The Jiu Tangshu adds that Songtsän Gampo thereupon built a city for the Chinese princess, and a palace for her within its walls.

- "As the princess disliked their custom of painting their faces red, Lungstan (Songtsän Gampo) ordered his people to put a stop to the practice, and it was no longer done. He also discarded his felt and skins, put on brocade and silk, and gradually copied Chinese civilization. He also sent the children of his chiefs and rich men to request admittance into the national school to be taught the classics, and invited learned scholars from China to compose his official reports to the emperor."[56]

However, according to Tibetologist John Powers, such accounts of Tibet embracing Chinese culture through Wencheng are not corroborated by Tibetan histories.[57]

Songtsän Gampo's sister Sad-mar-kar was sent to marry Lig-myi-rhya, the king of Zhangzhung. However, when the king refused to consummate the marriage, she then helped Songtsän Gampo to defeat Lig myi-rhya and incorporate the Zhangzhung of Western Tibet into the Tibetan Empire in 645,[53] thus gaining control of most, if not all, of the Tibetan plateau.

Following the visit by the famous Chinese pilgrim monk Xuanzang to the court of Harsha, the king ruling Magadha, Harsha sent a mission to China which, in turn, responded by sending an embassy consisting of Li Yibiao and Wang Xuance, who probably travelled through Tibet and whose journey is commemorated in inscriptions at Rajagrha - modern Rajgir – and Bodhgaya.

Wang Xuanze made a second journey in 648, but he was badly treated by Harsha's usurper, his minister Arjuna, and Harsha's mission plundered. This elicited a response from Tibetan and Nepalese (Licchavi) troops who, together, soundly defeated Arjuna's forces.[58][59]

In 649, the King of Xihai Jun was conferred upon Songtsen Gampo by Tang Gaozong, the emperor of the Tang Dynasty.

According to the Tibetan Annals, Songtsän Gampo must have died in 649,[60] and, in 650, the Tang emperor sent an envoy with a "letter of mourning and condolences".[61] His tomb is in the Chongyas Valley near Yalung.[62]

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ a b Shakabpa 1967, p. 25.

- ^ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, pp. 161, b.449, 191 n.560.

- ^ Beckwith 1993, p. 19 n. 31..

- ^ Yeshe De Project 1986, pp. 222–225.

- ^ Laird 2006.

- ^ Dotson 2006, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Ancient Tibet: Research materials from the Yeshe De Project. 1986. Dharma Publishing, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3, p. 216.

- ^ Choephel, Gedun. The White Annals. Translated by Samten Norboo. (1978), p. 77. Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

- ^ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 161 note 447.

- ^ a b bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 904.

- ^ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 913.

- ^ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 302 note 910.

- ^ bsod nams rgyal mtshan 1994, p. 200 note 562.

- ^ Gyatso & Havnevik 2005.

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History, p. 27. Yale University Press. New Haven and London.

- ^ Ancient Tibet: Research materials from the Yeshe De Project. 1986. Dharma Publishing, California. ISBN 0-89800-146-3, p. 215, 224-225.

- ^ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 63. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk.

- ^ Gyaltsen, Sakyapa Sonam (1312-1375). The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age, p. 192. Translated by McComas Taylor and Lama Choedak Yuthob. (1996) Snow Lion Publications, Ithaca, New York. ISBN 1-55939-048-4.

- ^ a b Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 443.

- ^ Beckwith 1993, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications, London, p. 70. ISBN 0-906026-25-3

- ^ a b Snellgrove, David. 1987. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism: Indian Buddhists and Their Tibetan Successors. 2 Vols. Shambhala, Boston, Vol. II, p. 372.

- ^ Dudjom 1991.

- ^ Dorje (1999), p. 201.

- ^ Beckwith (1987), p. 25, n. 71.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 446.

- ^ Sakyapa Sonam Gyaltsen. (1328). Clear Mirror on Royal Genealogy. Translated by McComas Taylor and Lama Choedak Yuthok as: The Clear Mirror: A Traditional Account of Tibet's Golden Age, p. 106. (1996) Snow Lion Publications. Ithica, New York. ISBN 1-55939-048-4.

- ^ Anne-Marie Blondeau, Yonten Gyatso, 'Lhasa, Legend and History,' in Françoise Pommaret(ed.) Lhasa in the seventeenth century: the capital of the Dalai Lamas, Brill Tibetan Studies Library, 3, Brill 2003, pp.15-38, pp15ff.

- ^ Amund Sinding-Larsen, The Lhasa atlas: : traditional Tibetan architecture and townscape, Serindia Publications, Inc., 2001 p.14

- ^ "Buddhism - Kagyu Office". 2009-01-10.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. A Corpus of Early Tibetan Inscriptions (1981), p. 75. Royal Asiatic Society, London. ISBN 0-947593-00-4.

- ^ Beckwith, C. I. "The Revolt of 755 in Tibet", p. 3 note 7. In: Weiner Studien zur Tibetologie und Buddhismuskunde. Nos. 10-11. [Ernst Steinkellner and Helmut Tauscher, eds. Proceedings of the Csoma de Kőrös Symposium Held at Velm-Vienna, Austria, 13–19 September 1981. Vols. 1-2.] Vienna, 1983.

- ^ Lee 1981, pp. 6-7

- ^ Powers 2004, pg. 31

- ^ Karmey, Samten G. (1975). "'A General Introduction to the History and Doctrines of Bon", p. 180. Memoirs of Research Department of The Toyo Bunko, No, 33. Tokyo.

- ^ a b Powers 2004, pp. 168-9

- ^ Lee 1981, pp. 7-9

- ^ Pelliot 1961, pp. 3-4

- ^ Norbu, Namkhai. (1981). The Necklace of Gzi, A Cultural History of Tibet, p. 30. Information Office of His Holiness The Dalai Lama, Dharamsala, H.P., India.

- ^ Beckwith (1987), p. 20. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Fourth printing with new afterword and 1st paperback version. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

- ^ Allen, Charles. The Search for Shangri-La: A Journey into Tibetan History, pp. 127-128. (1999). Reprint: (2000). Abacus, London. ISBN 0-349-11142-1.

- ^ Stein, R. A. (1972). Tibetan Civilization, p. 59. Stanford University Press, Stanford California. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 (cloth); ISBN 0-8047-0901-7.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 443-444.

- ^ Beckwith (1987), pp. 22-23.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 528, n. 13

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 444.

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1965). "How Old was Srong Brtsan Sgampo," Bulletin of Tibetology 2.1. pp. 5-8.

- ^ OTA l. 8-10

- ^ Pelliot 1961, pg. 12

- ^ Vitali, Roberto. 1990. Early Temples of Central Tibet. Serindia Publications, London, p. 71. ISBN 0-906026-25-3

- ^ Chavannes, Édouard . Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux. 1900. Paris, Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient. Reprint: Taipei. Cheng Wen Publishing Co. 1969, p. 186.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 529, n. 31.

- ^ a b Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk., p. 59.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, pp. 529-530, n. 31.

- ^ Das, Sarat Chandra. (1902), Journey to Lhasa and Central Tibet. Reprint: Mehra Offset Press, Delhi. 1988, p. 165, note.

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 545.

- ^ Powers 2004, pp. 30-38

- ^ Stein, R. A. Tibetan Civilization 1962. Revised English edition, 1972, Faber & Faber, London. Reprint, 1972. Stanford University Press, p. 62. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1 cloth; ISBN 0-8047-0901-7 pbk., pp. 58-59

- ^ Bushell, S. W. "The Early History of Tibet. From Chinese Sources." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. XII, 1880, p. 446

- ^ Bacot, J., et al. Documents de Touen-houang relatifs à l'Histoire du Tibet. (1940), p. 30. Libraire orientaliste Paul Geunther, Paris.

- ^ Lee 1981, p. 13

- ^ Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. Tibet: A Political History (1967), p. 29. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Sources

- Beckwith, Christopher I (1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02469-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - bsod nams rgyal mtshan (1994). The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies: Tibetan Buddhist Historiography : an Annotated Translation of the XIVth Century Tibetan Chronicle: RGyal-rabs Gsal- Baʼi Me-long. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-03510-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dotson, Brandon (2006), Administration and Law in the Tibetan Empire:The Section on Law and State and its Old Tibetan Antecedents (D.Phil. Thesis, Tibetan and Himalayan Studies), Oriental Institute University of Oxford

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dudjom (1991). The Nyingma School of Tibetan Buddhism: Its Fundamentals and History. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-734-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gyatso, Janet; Havnevik, Hanna (2005). Women in Tibet. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13098-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gyurme Dorje (1999). Tibet Handbook: With Bhutan. Footprint Handbooks. ISBN 978-1-900949-33-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laird, Thomas (2006). The Story of Tibet: Conversations with The Dalai Lama. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1827-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, Don Y (1981). The History of Early Relations between China and Tibet: From Chiu t'ang-shu, a documentary survey. Bloomington: Eastern Press. ISBN 0-939758-00-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pelliot, Paul (1961). Histoire ancienne du Tibet. Paris: Librairie d'Amérique et d'orient.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Powers, John (2004). History as Propaganda Tibetan exiles versus the People's Republic of China ([Repr.]. ed.). New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517426-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richardson, Hugh E. (1965). "How Old was Srong Brtsan Sgampo". Bulletin of Tibetology. 2 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shakabpa, Tsepon W. D. (1967). Tibet: A Political History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yeshe De Project (1986). Ancient Tibet: Research Materials from the Yeshe De Project. Dharma Publ. ISBN 978-0-89800-146-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- http://www.asianart.com/articles/jaya/kings.html A list of Licchavi kings and their attributed dates, from: "A Kushan-period Sculpture from the reign of Jaya Varma-, A.D. 184/185. Kathmandu, Nepal." Kashinath Tamot and Ian Alsop. See: http://www.asianart.com/articles/jaya/index01_12.html