Spanish language in the Philippines

Spanish was the official language of the Philippines from the beginning of Spanish rule in the late 16th century, through the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in 1898. It remained, along with English, as co-official language until 1987. It was at first removed in 1973 by a constitutional change, but after a few months it was re-designated an official language by presidential decree and remained official until 1987, when the present Constitution removed its official status, designating it instead as an optional language.[1][2]

Philippine Spanish (Spanish: Español filipino, Castellano filipino) is a variant of standard Spanish, spoken in the Philippines by a minority today, though it was quite widespread up to the early 20th century. The variant is very similar to Mexican Spanish, because the Philippines was ruled from New Spain in present-day Mexico, for over two centuries. During that period, there was much Spanish and Mexican emigration to the Spanish East Indies.

It was the language of the Philippine Revolution and the country's first official language, as proclaimed in the Malolos Constitution of the First Philippine Republic in 1899. It was the language of commerce, law, politics and the arts during the colonial period and well into the 20th century. It was the main language of many classical writers and Ilustrados such as Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, Antonio Luna and Marcelo del Pilar, to name but a few. It is regulated by the Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española, the main Spanish-language regulating body in the Philippines, and a member of the Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española, the entity which regulates the Spanish language worldwide.

Background

Overview

Spanish was the language of government, education and trade throughout the three centuries of Spanish rule and continued to serve as a lingua franca until the first half of the 20th century.[3] Spanish was the official language of the Malolos Republic, "for the time being", according to the Malolos Constitution of 1899.[4] Spanish was also the official language of the Cantonal Republic of Negros of 1898 and the Republic of Zamboanga of 1899.[5]

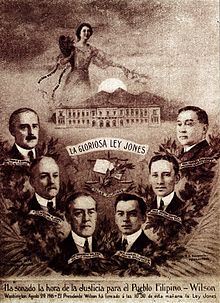

During the early part of the U.S. administration of the Philippine Islands, Spanish was widely spoken and relatively well maintained throughout the American colonial period.[3][6][7] Even so, Spanish was a language that bound leading men in the Philippines like Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera y Gorricho to President Sergio Osmeña and his successor, President Manuel Roxas. As a senator, Manuel L. Quezon (later President), delivered a speech in the 1920s entitled "Message to My People" in English and in Spanish.[8]

Official Language

Spanish remained an official language of government until a new constitution ratified on January 17, 1973 designated English and Pilipino, spelled in that draft of the constitution with a "P" instead of the more modern "F", as official languages. Shortly thereafter, Presidential Proclamation No. 155 dated March 15, 1973 ordered that the Spanish language should continue to be recognized as an official language so long as government documents in that language remained untranslated. A later constitution ratified in 1987 designated Filipino and English as official languages.[1] Also, under this Constitution, Spanish, together with Arabic, was designated an optional and voluntary language.[2]

Influence

There are thousands of Spanish loanwords in 170 native Philippine languages, and Spanish orthography has influenced the spelling system used for writing most of these languages.[9]

Demographics

According to the 1990 Philippine census, there were 2,660 native Spanish speakers in the Philippines.[10] In 2013 there were also 3,325 Spanish residents.[11] However, there are 439,000 Spanish speakers with native knowledge,[12] which accounts for just 0.5% of the population (92,337,852 at the 2010 census).[13] In 1998, there were 1.8 million Spanish speakers including those who spoke Spanish as a secondary language.[14]

Chavacano

In addition, an estimated 1,200,000 people speak Chavacano, a Spanish-based creole.[14] In 2010 the Instituto Cervantes de Manila put the number of Spanish speakers in the Philippines in the area of three million, which included the native and the non-native Chavacano and Spanish speakers as well since there are some Filipinos who can speak Spanish and Chavacano as a second, third, or fourth language.[15]

History

Spanish colonial period

Spanish was first introduced to the Philippines in 1565, when the conquistador, Miguel López de Legazpi, founded the first Spanish settlement on the island of Cebú.[16] The Philippines, ruled first from Mexico City and later from Madrid, was a Spanish territory for 333 years (1565–1898).[17] Schooling was a priority, however. The Augustinians opened a school immediately upon arriving in Cebú in 1565; the Franciscans followed suit when they arrived in 1577, as did the Dominicans when they arrived in 1587. Besides religious instruction, these schools taught how to read and write and imparted industrial and agricultural techniques.[18]

Initially, the stance of the Roman Catholic Church and its missionaries was to preach to the natives in local languages, not in Spanish. The priests learned the native languages and sometimes employed indigenous peoples as translators, creating a bilingual class known as Ladinos.[19] Before the 19th century, the natives generally were not taught Spanish. However, there were notable bilingual individuals such as poet-translator Gaspar Aquino de Belén. Gaspar produced Christian devotional poetry written in the Roman script in the Tagalog language. Pasyon is a narrative of the passion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ begun by Gaspar Aquino de Belén, which has circulated in many versions. Later, the Spanish-Mexican ballads of chivalry, the corrido, provided a model for secular literature. Verse narratives, or komedya, were performed in the regional languages for the illiterate majority.

In the early 17th century, a Tagalog-Chinese printer, Tomás Pinpin, set out to write a book in romanized phonetic script to teach the Tagalogs how to learn Castilian. His book, published by the Dominican press where he worked, appeared in 1610, the same year as Blancas's Arte. Unlike the missionary's grammar (which Pinpin had set in type), the Tagalog native's book dealt with the language of the dominant rather than the subordinate other. Pinpin's book was the first such work ever written and published by a Philippine native. As such, it is richly instructive for what it tells us about the interests that animated Tagalog translation and, by implication, Tagalog conversion in the early colonial period.

By law, each town had to build two schools, one for boys and the other for girls, to teach the Spanish language and the Christian catechism. There were never enough trained teachers, however, and several provincial schools were mere sheds open to the rain. This discouraged the attendance at school and illiteracy was high in the provinces until the 19th century, when public education was introduced. The conditions were better in larger towns. To qualify as an independent civil town, a barrio or group of barrios had to have a priest's residence, a town hall, boys' and girls' schools; streets had to be straight and at right angles to one another so that the town could grow in size; the town had to be near a good water source and land for farming and grazing.[20]

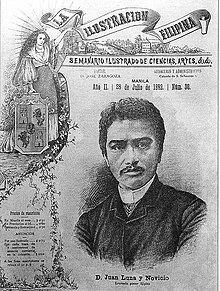

Better school conditions in towns and cities led to more effective instruction in the Spanish language and in other subjects. Between 1600 and 1865, a number of colleges and universities were established, which graduated many important colonial officials and church prelates, bishops, and archbishops—several of whom served the churches in Hispanic America. The increased level of education eventually led to the rise of the Ilustrados. In 1846, French traveler Jean Baptiste Mallat was surprised at how advanced Philippine schools were.[18] In 1865, the government inaugurated the Escuela Normal (Normal School), an institute to train future primary school teachers. At the same time, primary schooling was made compulsory for all children. In 1869, a new Spanish constitution brought to the Philippines universal suffrage and a free press.[21] El Boletín de Cebú, the first Spanish newspaper in Cebu City, was published in 1886.[22]

In Manila, the Spanish language had been more or less widespread, to the point where it has been estimated at around 50% of the population knew Spanish in the late 19th century.[23] In his 1898 book "Yesterdays in the Philippines", covering a period beginning in 1893, the American Joseph Earle Stevens, an American who resided in Manila from 1893 to 1894, wrote:

Spanish, of course, is the court and commercial language and, except among the uneducated native who have a lingua of their own or among the few members of the Anglo-Saxon colony, it has a monopoly everywhere. No one can really get on without it, and even the Chinese come in with their peculiar pidgin variety.[24]

Long contact between Spanish and the local languages, Chinese dialects, and later Japanese produced a series of pidgins, known as Bamboo Spanish, and the Spanish-based creole Chavacano. At one point these were the language of a substantial proportion of the Philippine population.[25] Unsurprisingly, given that the Philippines was administrated for centuries from New Spain in present-day Mexico, Philippine Spanish is broadly similar to American Spanish, not only in vocabulary, but in pronunciation and grammar.[26]

Although the Philippines were not as culturally hispanized as Hispanic America, the Spanish language was the official language used by the civil and judicial administration, and was spoken by the majority of the population and understood by just everyone, especially after the passing of the Education Decree of 1863. By the end of the 19th century, Spanish was a strong second language among the upper classes of Philippine society, having been learned in childhood either directly from parents and grandparents or through tutoring by a local priest.[27] By the time Spanish rule came to an end, Spanish was the language of more than 60% of the population.[6]

Schools

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the oldest educational institutions in the country were set up by Spanish religious orders. These schools and universities played a crucial role in the development of the Spanish language in the islands. Colegio de Manila in Intramuros was founded in 1590. The Colegio formally opened in 1595, and was one of the first schools in the Philippines.[28] During the same year, the University of San Carlos in Cebú, was established as the Colegio de San Ildefonso by the Jesuits. In 1611, the University of Santo Tomás, considered as the oldest existing university in Asia, was inaugurated in Manila by the Dominicans. In the 18th century, fluent male Spanish speakers in the Philippines were generally the graduates of these schools, as well as of the Colegio de San Juan de Letrán, established in 1620. In 1706, a convent school for Philippine women known as Beaterios was established. It admitted both Spanish and native girls, and taught Religion, Reading, Writing and Arithmetic with Music and Embroidery. Female graduates from Beaterios were fluent in the language as well. In 1859, Ateneo de Manila University was established by the Jesuits as the Escuela Municipal.[28]

In 1863, Queen Isabel II of Spain decreed the establishment of a public school system, following the requests of the Spanish authorities in the islands, who saw the need of teaching Spanish to the wider population. The primary instruction and the teaching of the Spanish language was compulsory. The Educational Decree provided for the establishment of at least one primary school for boys and girls in each town and governed by the municipal government. Normal school for male teachers was established and was supervised by the Jesuits.[29][30] In 1866, the total population of the Philippines was only 4,411,261. The total public schools was 841 for boys and 833 for girls and the total number of children attending these schools was 135,098 boys and 95,260 girls. In 1892, the number of schools had increased to 2,137, 1,087 of which were for boys and 1,050 for girls.[31] This measure was at the vanguard of contemporary Asian countries, and led to an important class of educated natives which sometimes followed their studies abroad, like national hero José Rizal, who studied in Europe. This class of writers, poets and intellectuals is often referred to as Ilustrados. Ironically, it was during the initial years of American occupation in the early 20th century, that Spanish literature and press flourished. This was the result both of a majority of Spanish-speaking population, as well as the partial freedom of the press which the American rulers allowed.

Filipino nationalism and 19th century Revolutionary governments

Before the 19th century, Philippine revolts were small-scale and did not extend beyond linguistic boundaries. Thus, they were easily neutralized by Spanish forces.[32] With the small period of the spread of Spanish through a free public school system (1863) and the rise of an educated class, nationalists from different parts of the archipelago were able to communicate in a common language. José Rizal's novels, Graciano López Jaena's satirical articles, Marcelo H. del Pilar's anti-clerical manifestos, the bi-weekly La Solidaridad which was published in Spain, and other materials in awakening nationalism were written in Spanish. The Philippine Revolution fought for reforms and later for independence from Spain. However, it did not oppose Spain's cultural legacy in the islands or the Spanish language.[33][34][35] Even Graciano López Jaena's La Solidaridad article in 1889 praised the young women of Malolos who petitioned to Governor-General Valeriano Weyler to open a night school to teach the Spanish language.[36] In fact, the Malolos Congress of 1899 chose Spanish as the official language. According to Horacio de la Costa, nationalism would not have been possible without Spanish.[32] by then increasingly aware of nationalistic ideas and independence movements in other countries.

Spanish was used by the first Filipino patriots like José Rizal, Andrés Bonifacio and, to a lesser extent, Emilio Aguinaldo. The 1896 Biak-na-Bato Constitution and the 1898 Malolos Constitution were both written in Spanish. Neither specified a national language, but both recognised the continuing use of Spanish in Philippine life and legislation.[4][37] Aguinaldo was more comfortable speaking Tagalog.[38] Spanish was used to write the Constitution of Biak-na-Bato, Malolos Constitution, the original national anthem, Himno Nacional Filipino, as well as nationalistic propaganda material and literature.

The country's first two constitutions and historic novels were written in Spanish. While widely understood by the majority of the population, Spanish at this time was the unifying language since Tagalog was not as prominent or ubiquitous as it is today and each region had their own culture and language, and would rather speak in their local languages. Before the spread of Filipino nationalism, the natives of each region still thought of themselves as Ilocano, Cebuano, Bicolano, Waray, Tagalog etc., and not as Filipinos.

The term "Filipino" originally referred to the natives of the Philippines themselves. It was Pedro Chirino, a Spanish Jesuit, who first called the natives "Filipinos," in his book Relación de las Islas Filipinas (Rome, 1604). However, during their 333-year rule of the Philippines, the Spanish rulers preferred to call the natives indios.[39]

Also during the colonial era, the Spaniards born in the Philippines, who were more known as insulares, criollos, or Creoles, were also called "Filipinos." Spanish-born Spaniards or mainland Spaniards residing in the Philippines were referred to as Peninsulares. Peoples born in Spanish America or in the North American continent of New Spain who were residing in the Philippines were collectively referred to as Americanos. The Catholic Austronesian peoples of the Philippines were referred to as Indios and for those who were practicing the Islamic faith, Moros. The indigenous Aetas were referred to as Negritos. Chinese settlers were called Sangleyes. Japanese settlers were called Japoneses. Those of mixed ancestry were referred to as Mestizos or Tornatrás. In the 1800s, the term "Filipino" gradually became synonymous to anyone born in the Philippines regardless of ethnicity through the effort of the Insulares, from whom, Filipino nationalism began.

In 1863, the Spanish language was taught freely when a primary public school system was set up for the entire population. The Spanish-speaking Ilustrados (The Enlightened Ones), which included the Insulares, the Indios, the Mestizos, the Tornatrás, etc., were the educated elite who promoted and propagated nationalism and a modern Filipino consciousness. The Ilustrados and later writers formed the basis of Philippine Classical Literature which developed in the 19th century.

José Rizal propagated Filipino consciousness and identity in Spanish. One material highly instrumental in developing nationalism was the novels entitled Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo which exposed the abuses of the colonial government and clergy composed of Peninsulares. The novels' very own notoriety propelled its popularity even more among Filipinos. Reading it was forbidden because it exposed and parodied the Peninsulares in the Philippine Islands.

Philippine–American War

The revolutionary Malolos Republic of 1899 designated the Spanish language for official use in its constitution, drawn up during the Constitutional Convention in Malolos, Bulacan.[4][6][40] During this period, the nascent republic published a number of laws, acts, decrees, and other official issuances. These were published variously in the Spanish, English, and Tagalog languages, with the Spanish language predominating.[41] Spanish was also designated the official language of the Cantonal Republic of Negros of 1898 and the Republic of Zamboanga of 1899.[5]

Many Spanish-speaking Filipino families perished during the Philippine–American War. According to the historian James B. Goodno, author of the Philippines: Land of Broken Promises (New York, 1998), one-sixth of the total population of Filipinos or about 1.5 million died as a direct result of the war.[6][42][43][44]

American colonial period

With the era of the Philippines as a Spanish colony with its people as Spanish citizens[45] having just ended, a considerable amount of media, newspapers, radios, and government proceedings were still written and produced in Spanish. By law, the Taft Commission allowed their guests to use the language of their choice.[46] Ironically, the partial freedom of the press allowed by the American rulers served to further promote Spanish-language literacy among the masses. Even in the early 20th century, a hegemony of Spanish language was still in force.[3]

While the census of 1903 and of 1905 officially reported that the number of Spanish-speakers have never exceeded 10% of the total population during the final decade of the 19th century, it only considered Spanish speakers as their first and only language. It disregarded the Catholic Chinese Filipinos, many of whom spoke Spanish, and the creole-speaking communities.[6] Furthermore, those who were academically instructed in the public school system also used Spanish as their second or third language. These together would have placed the numbers at more than 60% of the 9,000,000 Filipinos of that era as Spanish-speakers.[6]

In the Eighth Annual Report by the Director of Education, David P. Barrows, dated August 1, 1908, the following observations were made about the use and extension of the Spanish language in the Philippines:[6][47]

Of the adult population, including persons of mature years and social influence, the number speaking English is relatively small. This class speaks Spanish, and as it is the most prominent and important class of people in the Islands, Spanish continues to be the most important language spoken in political, journalistic and commercial circles.

A 1916 report by Henry Jones Ford to President Woodrow Wilson said[48]

...as I traveled through the Philippine Islands, using ordinary transportation and mixing with all classes of people under all conditions. Although based on the school statistics it is said that more Filipinos speak English than any other language, no one can be in agreement with this declaration if they base their assessment on what they hear...

Spanish is everywhere the language of business and social intercourse...In order for anyone to obtain prompt service from anyone, Spanish turns out to be more useful than English...And outside of Manila it is almost indispensable. The Americans who travel around all the islands customarily use it.

The use of Spanish as an official language has been extended to January 1, 1920. Its general use seems to be spreading. Natives acquiring it learn it as a living speech. Everywhere they hear it spoken by leading people of the community and their ears are trained to its pronunciation. On the other hand, they (the natives) are practically without phonic standards in acquiring English and the result is that they learn it as a book language rather than as a living speech.

— Henry Jones Ford

Although the English language had begun to be heavily promoted and used as the medium of education and government proceedings, the majority of literature produced by indigenous Filipinos during this period was in Spanish.[23] Among the great Filipino literary writers of the period were Fernando M.a Guerrero, Rafael Palma, Cecilio Apóstol, Jesús Balmori, Manuel Bernabé, Trinidad Pardo de Tavera and Teodoro M. Kalaw.[49] This explosion of Spanish language in Philippine literature occurred because the middle and upper class Filipinos were educated in Spanish and Spanish language as a subject was offered in public schools. In 1936, Philippine sound films in Spanish began to be produced.[50] Filipinos experienced a partial freedom of expression, since the American authorities weren't too receptive to Filipino writers and intellectuals during most of the colonial period. As a result, Spanish had become the most important language in the country.[3]

Until the Second World War, Spanish was the language of Manila.[23] After the war, the English-speaking U.S. having won three wars [in 1898, against Spain (Spanish–American War); in 1913 (from Philippine–American War to Moro Rebellion) against the Filipino independence; in 1945 against Japan (Philippines Campaign)], the English language was imposed.[23]

Decline of the Spanish language

The Spanish language flourished in the first two decades of the 20th century due to the partial freedom of the press and as an act of defiance against the new rulers. Spanish declined due to the imposition of English as the official language and medium of instruction in schools and universities.[51][52] The American administration increasingly forced editorials and newspapers to switch to English, leaving Spanish in a marginal position, so that Enrique Zóbel de Ayala founded the Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española and the Premio Zóbel in 1924 to help maintain and develop the use of Spanish among the Filipino people.

It did not help when some Filipino nationalists and nationalist historiographers during the American Colonial Period who took their liberal ideas from the writings of the 19th century Filipino Propaganda which portrayed Spain and all things Spanish as negative or evil. Therefore, Spanish as a language was demonized as a sad reminder of the past.[53] These ideas gradually inculcated into the minds of the young generation of Filipinos (during and after the American administration) who used those history textbooks at school that tended to generalize all Spaniards as villains due to lack of emphasis on Filipino people of Spanish ancestry who were also against the local Spanish government and clergy and also fought and died for the sake of freedom during the 19th century revolts, during the Philippine Revolution, during the Philippine–American War and during World War II.[54][55][56]

By the 1940s as children educated in English became adults, the Spanish language was starting to decline rapidly. Still, a very significant community of Filipino Spanish-speakers lived in the bigger cities, with a total population of roughly 300,000. However, with the destruction of Manila during the Japanese occupation in World War II, the heart of the Spanish language in the Philippines was dismantled.[57][58][59] Many Spanish-speaking Filipino families perished during the massacre and bombing of the cities and municipalities between 1942 and 1945. At the end of the war, an estimated 1 million Filipinos lost their lives.[60] Some of those Spanish-speakers who survived were forced to migrate in the later years.

After the war, Spanish became increasingly marginalized at an official level. As English and American-influenced pop culture increased, the use of Spanish in all aspects gradually declined. In 1962, when President Diosdado Macapagal decreed that the Philippines mark independence day on June 12 instead of July 4 which the country gained complete independence from the United States, it revealed a tendency to paint Spain as the villain and the United States as saviour, or the more benevolent colonial power.[61] The Spanish language and Hispanic culture was demonized again.[51][failed verification] In 1973, Spanish briefly lost its status as an official language of the Philippines, was quickly redesignated as an official language, and finally did lose official status with the ratification of a subsequent constitution in 1987.[1]

21st-century developments

The 21st century has seen a revival of interest in the language, with the numbers of those studying it formally at college or taking private courses rising markedly in recent years.[62] Today, the Philippine constitution provides that Spanish shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.[63] A great portion of the history of the Philippines is written in Spanish and, up until recently, many land titles, contracts, newspapers and literature were still written in Spanish.[64] Today, Spanish is being somewhat revived in the Philippines by groups rallying to make it a compulsory subject in school.[65]

Republic Act No. 9187 was approved on February 5, 2003 and signed by President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo declaring June 30 of every year as Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day to commemorate the cultural and historical ties, friendship and cooperation between the Philippines and Spain.[66] On July 3, 2006, the Union of Local Authorities of the Philippines created Resolution No. 2006-028 urging the national government to support and promote the teaching of the Spanish language in all public and private universities and colleges in the Philippines.[67] On December 17, 2007, the Department of Education issued Memorandum No. 490, s. 2007 encouraging secondary schools to offer basic and advance Spanish in the 3rd and 4th year levels respectively, as an elective.[68] As of 2008[update], there was a growing demand for Spanish-speaking agents in the call center industry as well as in the business process outsourcing in the Philippines for the Spanish and American market. Around 7,000 students were enrolled in the Spanish language classes of the Instituto Cervantes de Manila for the school year 2007–2008.[69] On December 11, 2008, the Department of Education issued Memorandum No. 560, s. 2008 that shall implement the Special Program in Foreign Language on a pilot basis starting school year 2009–2010. The program shall initially offer Spanish as a foreign language in one school per region, at two classes of 35 students each, per school.[70] As of 2009, the Spanish government has offered to fund a project and even offered scholarship grants to Spain for public school teachers and students who would like to study Spanish or take up a master's degree in four top universities in Spain. The Spanish government has been funding the ongoing pilot teacher training program about the Spanish language, involving two months of face-to-face classes and a 10-month on-line component.[71] Clásicos Hispanofilipinos is a project of Instituto Cervantes de Manila which aims to promote Filipino heritage and preserve and reintroduce the works of great Fil-Hispanic authors of the early 20th century to the new generation of Filipino Hispanophones. The Spanish novel of Jesús Balmori entitled Los Pájaros de Fuego (Birds of Fire) which was mostly written during the Japanese occupation was published by the Instituto June 28, 2010.[72] King Juan Carlos I commented in 2007 that

In fact, some of the beautiful pages of Spanish literature were written in the Philippines.[73]

During her visit to the Philippines in July 2012, Sofia of Spain expressed her support for the Spanish language to be revived in Philippine schools.[74][75]

On September 11, 2012, saying that there were 318 Spanish-trained basic education teachers in the Philippines, Philippine secretary of the Department of Education Armin Luistro announced an agreement with the Chilean government to train Filipino school teachers in Spanish. In exchange, the Philippines would help train Chilean teachers in English.[76]

Influence on the languages of the Philippines

There are approximately 4,000 Spanish words in Tagalog (between 20% and 33% of Tagalog words),[62] and around 6,000 Spanish words in Visayan and other Philippine languages. The Spanish counting system, calendar, time, etc. are still in use with slight modifications. Archaic Spanish words have been preserved in Tagalog and the other vernaculars, such as pera (coins), sabón [(Spanish: jabón) at the beginning of Spanish rule, the j used to be pronounced [ʃ], the voiceless postalveolar fricative or the "sh" sound; (soap)], relos [(Spanish: reloj) with the j sound; (watch)], kwarta (Old Spanish: cuarta; money), etc.[77] The Spaniards and the language are referred to as either Kastila or Katsila (mostly Visayan languages) after Castilla (Castile), the original Spanish Kingdom under which Spain was unified in 1492, which later became a Spanish region.

Chavacano, also called Zamboangueño, is a Spanish-based creole language spoken mainly in the southern province of Zamboanga and, to a much lesser extent, in the province of Cavite in the northern region of Luzon.[78] Chavacano became the main language in the Zamboanga City and some parts of Zamboanga Peninsula, as a result of the migration into the area of a large number of workers, who came from different linguistic regions to build military and other Spanish establishments.

Morphosemantic changes

While many Spanish words have entered Tagalog, Cebuano and other Philippine languages, many of the words have seen a shift in meaning and even construction from the original Spanish. That has resulted in false friends, similar words in both languages but with a different meaning. A sample is shown below:

| Word | Language | Meaning in the Philippines | Original Spanish word | Spanish meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| asár | Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as asá meaning roast or to roast) | to annoy | asar | roast |

| astá | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (hasta meaning until or til then) | rude movements | hasta (in Arabic: Hatta) Influences from Latin ad ista (“to this”) | until |

| bale | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (spelled as Vale for nice, beautiful) | well and worth, ie/'that is to say'/namely, wages, advance pay | vale | ok! and voucher or promissory note |

| balón | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Visayan, Chavacano | well/balloon | balón | ball |

| banda | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano | within proximity of and band | banda | band, side |

| baráto | Tagalog, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Kapampangan | cheap | barato | cheap, low prices |

| barkada | Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, Pangasinense, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon | group of friends | barcada | boatload |

| basta | Tagalog, Chavacano (also retains original meaning), Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Kapampangan | as long as/secret | basta | enough, stop! |

| bida | Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as Vida) | lead actor or actress | vida | life |

| bomba | Cebuano, Tagalog, Ilocano, Pangasinense, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (also retains its meaning) | erotica/nudity and bomb | bomba | bomb, and impressive or surprising (slang) used as an exclamation ("la bomba!") |

| chika | Cebuano, Tagalog, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as Chica) | gossip and girl | chica | girl, small |

| entonses | Tagalog, Chavacano (spelled as entonces for 'then, afterwards') | elite class | entonces | then, afterwards |

| hurado | Tagalog, Bikol, Cebuano, Chavacano (spelled as jurado), Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Waray | judge or juror (in contests only) | jurado | juror, jury |

| impakto | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Cebuano, Hiligaynon | spirit causing temporary madness (originally elemental spirit from the earth) | impacto | impact, shock |

| kasilyas | Tagalog, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (spelled as "casillas"), Ilocano | bathroom, toilet | casilla | square, cube, hut |

| kerida | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (spelled as Querido or Querida. same meaning as beloved) | mistress (only) | querida | dear (used for female loved ones including mothers, sisters, aunts, and friends) and mistress (when used as "la querida") |

| kontrabida | Tagalog, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Chavacano (spelled as Contra Vida with the same meaning) | villain | contra vida | against life |

| konyo | Tagalog, Chavacano (spelled as coño. synonyms to cúlo. also retain its meaning same in spanish "curse word or to be specific 'vagina') | rich or vain | coño | vagina (vulgar expletive) |

| kubeta | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as Cúbeta) | toilet, outhouse | cubeta | bucket |

| kumustá | Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Cebuano | hello or How are you? / How is ___? | ¿Cómo está? | How are you? / How is ___? (only) |

| kuwarta | Cebuano, Hiligayno | money | cuarta | fourth, quarter (coin) |

| labakara | Tagalog, Ilokano, Bikol, Kapampangan, Cebuano, Waray | washcloth | lavacara | washbasin |

| lola | Tagalog, Visayan, and other Philippine languages | grandmother | Lola | derived from final syllable of abuela (grandmother) [See also 'lolo' from Abuelo] |

| madre | Cebuano, Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (also retain its meaning "mother") | nun (only) | madre | mother (parent) and nun |

| maldito/ maldita |

Cebuano, Tagalog, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Hiligaynon, Chavacano | bad | maldito/ maldita |

bad, damned, cursed |

| mamón | Tagalog, Cebuano, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (mamón, it means "cake") | fluffy bread | mamón (de "mamar"), mamón (de "mamas"), mamón (type of Mexican bread) | suckle (from mamar "to suckle") mammary glands (as in the English word "mammaries") Also papaya in the Caribbean |

| maské, maskí | Tagalog, Chavacano (spelled masquen or mas que), Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Kapampangan | even if | por más que/ más que | as much as; even if; even then;/more than |

| mutsatsa | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as Muchacha or Muchacho) | maid (only) | muchacha | maid (Mexico and Spain) and girl |

| onse | Tagalog, Ilocano, Cebuano, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (spelled as 'Once') | eleven, hustle | once | eleven |

| padre | Cebuano, Tagalog, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Pangasinense, Kapampangan | priest (only, inflexible) | padre | father (parent), priest |

| palengke | Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as palenque. mostly used that word "tiange or mercado") | market | palenque | palisade |

| pare | Tagalog, Kapampangan | friend (slang) | Corruption of compadre, and not to be confused with pare, the polite imperative of stop. | godfather of one's child, friend |

| parì | Cebuano, Tagalog, Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Chavacano (Spelled as Parí "giving birth") (spelled padi), Kapampangan | priest | padre | father, priest |

| pera | Tagalog, Kapampangan | money | perra | coin, penny |

| peras | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon | pear | pera | pear |

| pirmi | Hiligaynon, Cebuano, Chavacano(spell it as "firmi", while "Firme" is firm in English), Kapampangan | steady, always | firme | firm, steady |

| pitsó | Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano (spelled as Pecho) | chicken breast (only) | pecho | breast (in general including humans and other animals) |

| puwerta | Tagalog, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon (also pertahan), Chavacano (spelled as Puerta) | door (also, in some instances, used to describe the orifice of the vaginal canal) | puerta | door |

| regla | Tagalog, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon, Chavacano | menstruation | regla | rule/ruler/menstruation |

| siguro | Tagalog, Chavacano (seguro. also retains its meaning), Cebuano, Ilocano, Hiligaynon, Kapampangan | maybe | seguro | secure, stable, sure |

| silbí | Tagalog, Cebuano, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as Servi) | to serve | sirve | He/she/it serves |

| siyempre | Tagalog, Ilocano, Chavacano(spelled as siempre for "of course" and "always"), Cebuano, Hiligaynon | of course | siempre | always |

| sugál | Tagalog, Cebuano,Hiligaynon, Ilocano, Pangasinense, Kapampangan | gambling | jugar | to play, to gamble |

| sugaról | Cebuano, Kapampangan, Hiligaynon | gambler | jugador | gambler and player |

| suplado | Tagalog, Cebuano, Pangasinense, Hiligaynon, Kapampangan, Chavacano (spelled as suplado or suplada) | snobbish, snooty, stubborn (child), brat | soplado | blown, inflated |

| sustansiya | Tagalog, Bikol, Cebuano, Chavacano (spelled as sustansia), Hiligaynon, Kapampangan, Pangasinense, Ilocano, Waray | nutrient | sustancia | substance |

False cognates

The following words do not fall under false friends. They are still a source of confusion:

| Word | Language | Meaning in the Philiippines | Similar Spanish word | Spanish meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alamín | Tagalog | to know; the root word 'alám' means 'know' - ultimately derived from Arabic. | alamín | village judge who decided on irrigation distribution or official who measured weights |

| luto | Tagalog, Cebuano, Waray | v., to cook (Tagalog, Cebuano) cooked rice (Waray); adj. cooked |

luto | mourning |

| lupà | Tagalog | earth, soil | lupa | magnifying glass |

| matá | Tagalog, Hiligaynon, Cebuano, Waray | eye | mata | '(He) kills.', hassock, clamp, tuft |

| piso | Tagalog, Cebuano, Waray | Philippine peso | piso | floor |

| puto | Tagalog, Visayan | A rice cake/fudge | puto | Male prostitute (pejorative:homosexual) |

| sabi | Tagalog, Ilokano, Bikol, Kapampangan | said | sabes | you know |

List of Spanish words of Philippine origin

Although the greatest linguistic impact and loanwords have been from Spanish to the languages of the Philippines, the Philippine languages have also loaned some words to Spanish.

The following are some of the words of Philippine origin that can be found in the Diccionario de la lengua española de la Real Academia Española, the dictionary published by the Real Academia Española:[79]

| Spanish loan word | Origin | Via | Tagalog | English equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| abacá | Old Tagalog: abacá | abaká | abaca | |

| baguio | Old Tagalog: baguio | bagyo | typhoon or hurricane | |

| barangay | Old Tagalog: balan͠gay | baranggay/barangay | barangay | |

| bolo | Old Tagalog: bolo | bolo | bolo | |

| carabao | Old Visayan: carabáo | kalabáw | carabao | |

| caracoa | Old Malay: coracora | Old Tagalog: caracoa | karakaw | caracoa, a war canoe |

| cogón | Old Tagalog: cogón | kogón | cogon | |

| dalaga | Old Tagalog: dalaga | dalaga | single, young woman | |

| gumamela | Old Tagalog: gumamela | gumamela | Chinese hibiscus | |

| nipa | Old Malay: nipah | Old Tagalog: nipa | nipa | nipa palm |

| paipay | Old Tagalog: paypay or pay-pay | pamaypay | a type of fan | |

| palay | Old Tagalog: palay | palay | unhusked rice | |

| pantalán | Old Tagalog: pantalán | pantalán | wooden pier | |

| salisipan | Old Tagalog: salicipan | salisipan | salisipan, a pirate ship | |

| sampagita | Old Tagalog: sampaga | sampagita | jasmine | |

| sawali | Old Tagalog: sauali | sawali | sawali, a woven bamboo mat | |

| tuba | Old Tagalog: tuba | tuba | palm wine | |

| yoyó | Ilocano: yoyo | Ilocano: yoyó | yo-yó | yo-yo |

Media

Spanish-language media is still present in the Philippines, the country has one Spanish newspaper, E-Dyario, the first Spanish digital newspaper published in the Philippines, and Filipinas, Ahora Mismo was a nationally syndicated, 60-minute, cultural radio magazine program in the Philippines broadcast daily in Spanish.

See also

- Hispanic influence on Filipino culture

- Latin Union

- Filipinas, Ahora Mismo

- Philippine Academy of the Spanish Language

- Philippine literature in Spanish

- Philippine Spanish

- Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day

- Philippines education during Spanish rule

- Spanish Filipino

Notes

- ^ a b c Article XIV, Section 3 of the 1935 Philippine Constitution provided, "[...] Until otherwise provided by law, English and Spanish shall continue as official languages." The 1943 Philippine Constitution (in effect during occupation by Japanese forces, and later repudiated) did not specify official languages. Article XV, Section 3(3) of the 1973 Philippine constitution ratified on January 17, 1973 specified, "Until otherwise provided by law, English and Pilipino shall be the official languages. Presidential Decree No. 155 dated March 15, 1973 ordered, "[...] that the Spanish language shall continue to be recognized as an official language in the Philippines while important documents in government files are in the Spanish language and not translated into either English or Pilipino language." Article XIV Section 7 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution specified, "For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English."

- ^ a b Article XIV, Sec 7: For purposes of communication and instruction, the official languages of the Philippines are Filipino and, until otherwise provided by law, English. The regional languages are the auxiliary official languages in the regions and shall serve as auxiliary media of instruction therein. Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.

- ^ a b c d Rodao, Florentino (1997). "Spanish language in the Philippines : 1900–1940". Philippine studies. 12. 45 (1). Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press: 94–107. ISSN 0031-7837. OCLC 612174151. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b c The Malolos Constitution was written in Spanish, and no official English translation was released. Article 93 read, "Artículo 93.° El empleo de las lenguas usadas en Filipinas es potestativo. No puede regularse sino por la ley y solamente para los actos de la autoridad pública y los asuntos judiciales. Para estos actos se usará por ahora la lengua castellana.";

A literal translation originally printed as exhibit IV, Volume I, Report of the Philippine Commission to the President, January 31, 1900, Senate Document 188. Fifty-sixth Congress, first session.) read, "ART.93 The use of the languages spoken in the Philippines is optional. It can only be regulated by law, and solely as regards acts of public authority and judicial affairs. For these acts, the Spanish language shall be used for the time being.", Kalaw 1927, p. 443;

In 1972, the Philippine Government National Historical Institute (NHI) published Guevara 1972, which contained a somewhat different English translation in which Article 93 read, "Article 93. The use of languages spoken in the Philippines shall be optional. Their use cannot be regulated except by virtue of law, and solely for acts of public authority and in the courts. For these acts the Spanish language may be used in the meantime." Guevara 1972, p. 117;

Other translations also exist (e.g. Rodriguez 1997, p. 130);

As of 2008, the NHI translation seems to predominate in publication, with some sources describing it as "official" or "approved": Rappa & Wee 2006, p. 67; Woods 2005, p. 218; Corpus Juris; LawPhil; (others). - ^ a b "History of The Republic of Zamboanga (May 1899 – March 1903)". Zamboanga City, Philippines: Zamboanga (zamboanga.com). July 18, 2009. Archived from the original on August 2, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c d e f g Gómez Rivera, Guillermo. "Statistics: Spanish Language in the Philippines". Circulo Hispano-Filipino. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (February 11, 2001). "The Librada Avelino-Gilbert Newton Encounter (Manila, 1913)". Spain: Buscoenlaces. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ "Talumpati: Manuel L. Quezon". Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (April 10, 2001). "The evolution of the native Tagalog alphabet". Philippines: Emanila Community (emanila.com). Views & Reviews. Archived from the original on August 3, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Languages of the Philippines". Ethnologue. Retrieved 2009-08-22.

- ^ "Instituto Nacional de Estadística". ine.es.

- ^ realinstitutoelcano.org, 2007

- ^ Medium projection, PH: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2010

- ^ a b Quilis, Antonio (1996), La lengua española en Filipinas (PDF), Cervantes virtual, p. 54 and 55

- ^ "El retorno triunfal del español a las Filipinas". Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ^ Arcilla 1994, pp. 7–11

- ^ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 80, 212

- ^ a b Arcilla 1994, p. 50

- ^ Villareal, Corazón (January 17–20, 2006). "Language and Desire in Hiligaynon" (PDF). Tenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

But the real authors were really the Ladinos, natives from the Philippine who were the informants, translators, or even better, consultants of the missionaries.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Arcilla 1994, p. 48

- ^ Beck, Sanderson. "Summary and Evaluation". Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ "Newspaper". Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ a b c d Rodríguez-Ponga

- ^ Stevens 1898, p. 11

- ^ Penny & Penny 2002, pp. 29–30

- ^ Penny & Penny 2002, pp. 30

- ^ Paul A. Kramer (2006). Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8078-7717-3.

- ^ a b "The First Hundred Years Of The Ateneo de Manila". Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ "Historical Perspective of the Philippine Educational System". Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^ "EDUCATION". Retrieved 2010-06-29.

- ^

Quezon, Manuel Luis (1915). "Escuelas públicas durante el régimen español". Philippine Assembly, Third Legislature, Third Session, Document No.4042-A 87 Speeches of Honorable Manuel L. Quezon, Philippine resident commissioner, delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States during the discussion of Jones Bill, 26 September-14 October 1914 (in Spanish). Manila, Philippines: Bureau of Printing. p. 35. Archived from the original on July 18, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_chapter=ignored (|trans-chapter=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Guerrero 1987

- ^ López Jaena, Graciano (February 15, 1889). "La Solidaridad : Our purposes". Barcelona, Spain: La Solidaridad. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ del Pilar, Marcelo (February 15, 1889). "The teaching of Spanish in the Philippines". Barcelona, Spain: La Solidaridad. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ del Pilar, Marcelo H. (April 25, 1889). "The aspirations of the Filipinos". Barcelona, Spain: La Solidaridad. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ López Jaena, Graciano (February 15, 1889). "Congratulations to the young women of Malolos". Barcelona, Spain: La Solidaridad. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved July 14, 2010.

- ^ Gonzalez, Andrew (1998). "The Language Planning Situation in the Philippines" (PDF). Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 19 (5&6): 513. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-14.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Gonzalez 1998, p. 521 (Note 7)

- ^ Jon E. Royeca. "Jon E. Royeca". jonroyeca.blogspot.com.

- ^ "1899 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines Title XIV Article 93". Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ^ Guevara 1972, p. Contents

- ^ Goodno, James B. (1991). The Philippines: land of broken promises. Zed Books. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-86232-862-7.

- ^ Filipinos and Americans during the Philippine–American War (producer: fonsucu) (September 26, 2009). Forgotten Filipinos/The Filipino genocide. YouTube (youtube.com). Retrieved July 30, 2010.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|people= - ^ Filipinos and Americans during the Philippine–American War (producer: fonsucu) (September 26, 2009). El genocidio filipino/Los filipinos olvidados. YouTube (youtube.com). Retrieved July 30, 2010.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|people= - ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (September 20, 2000). "The Filipino State". Spain: Buscoenlaces (buscoenlaces.es). Archived from the original on August 5, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Escalante 2007, p. 88

- ^ Eighth Annual Report, David P. Barrows, August 1, 1908, Bureau of Printing, 1957, Manila (P.94. Op.Cit.)

- ^ Guillermo Gómez Rivera. "The Thomasites, Before and After". emanila.com. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Resil B. Mojares, Philippine Literature in Spanish (archived from the original on 2005-11-25).

- ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (April 10, 2003). "Cine filipino en español" (in Spanish). Spain: Buscoenlaces (buscoenlaces.es). Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (March 2001). "Educadores y sabios adredemente olvidados" (in English and Spanish). Canada: La Guirnalda Polar (lgpolar.com). Núm. 53 – Especial de Filipinas I. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Gómez Rivera, Guillermo (February 11, 2001). "The Librada Avelino-Gilbert Newton Encounter (Manila, 1913)". Spain: Buscoenlaces (buscoenlaces.es). Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Ocampo, Ambeth (December 4, 2007). "The loss of Spanish". Makati City, Philippines: Philippine Daily Inquirer (INQUIRER.net). Opinion. Archived from the original on July 26, 2010. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^

Ocampo, Ambeth (March 1, 2002). "The Spanish friar, beyond the propaganda". Makati City, Philippines: Philippine Daily Inquirer (INQUIRER.net, previously inq7.net). Opinion. Archived from the original on April 13, 2002. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Filipino prisoners, Philippine–American War (producer: fonsucu) (December 7, 2009). Filipino Prisoners of War. YouTube (youtube.com). Event occurs at 1:26. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

Filipinos made prisoners by the USA army during the Philippine–American War

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|people= - ^ Military, politicians, priests and writers who opposed the American colonial domination (producer: fonsucu) (September 19, 2009). Filipinos hispanos/Hispanic Filipinos. YouTube (youtube.com). Retrieved July 27, 2010.

The invasion of the Philippines by the USA was fiercely resisted. Millions of Filipinos perished as a result of the American genocidal tactics.

{{cite AV media}}: External link in|people= - ^ Bernad, Miguel A. "Genocide in Manila". California, USA: Philippine American Literary House (palhbooks.com). PALH Book Reviews. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Quezon III, Manuel L. (February 7, 2007). "The Warsaw of Asia: How Manila was Flattened in WWII". Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: Arab News Online (archive.arabnews.com). Opinion. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ "The Sack of Manila". The Battling Bastards of Bataan (battlingbastardsbataan.com). Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ "Background Note: Philippines". U.S.A.: U.S. Department of State (state.gov). American Period. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2010.

- ^ Son, Johanna (June 9, 1998). "PHILIPPINES: Torn Between Two Colonisers – Spain and America". Manila, Philippines: oneworld.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 1999. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ a b Rodríguez Ponga, Rafael. "New Prospects for the Spanish Language in the Philippines (ARI)". Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Constitutional Commission of 1986 (October 15, 1986). "The 1987 Philippine Constitution (Article XIV-Education Section 7-Language)". Philippines: ilo.org. p. 28 Article XIV (Education) Section 7 (Language). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 16, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

Spanish and Arabic shall be promoted on a voluntary and optional basis.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The National Archives (archived from the original on 2007-09-27), Houses the Spanish Collection, which consists of around 13 million manuscripts from the Spanish colonial period.

- ^ "Spanish is once again a compulsory subject in the Philippines". Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Congress of the Philippines (2003). "Republic Act No. 9187: An Act declaring June 30 of the year as Philippine–Spanish Friendship Day, appropriating funds therefor and for other purposes". Metro Manila, Philippines. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Union of Local Authorities of the Philippines (ULAP) (July 3, 2006). "Resolution No. 2006-028: Urging the national government to support and promote the teaching of the Spanish language in all public and private universities and colleges in the Philippines". Manila, Philippines: ulap.gov.ph. Archived from the original on September 2, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Labrador, Vilma. "DepEd Memorandum No. 490, s. 2007 – The Spanish Language as an Elective in High School". Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Uy, Veronica (November 19, 2008). "Demand for Spanish speakers growing". Makati City, Philippines: Philippine Daily Inquirer (INQUIRER.net). Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Sangil Jr., Teodosio. "DepEd Memorandum No. 560, s. 2008 – Special Program in Foreign Language". Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Tubeza, Philip. "Scholarships for teachers to learn Spanish". Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ "Instituto Cervantes publishes Jesús Balmori's 'Los Pajáros de Fuego'". Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

{{cite web}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ Ubac, Michael Lim (December 5, 2007). "Spain's king hails Arroyo, RP democracy". Makati City, Philippines: Philippine Daily Inquirer (INQUIRER.net). Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

In fact, some of the beautiful pages of Spanish literature were written in the Philippines

- ^ "Queen Sofia wants Spanish back in Philippine public schools". The Philippine Star (philstar.com). July 5, 2012.

- ^ Legaspi, Amita O. (July 3, 2012). "PNoy (President Benigno Aquino III) and Spain's Queen Sofia welcome return of Spanish language in Philippine schools". GMA News.

- ^ Mangunay, Kristine. "DepEd mulls Spanish for students". Retrieved 13 September 2012.

- ^ "El español en Filipinas". Archived from the original on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Lipski, John M. "Chabacano, Spanish and the Philippine Linguistic Identity". Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ "REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA". Retrieved 2010-06-19.

Bibliography

- "1899 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines (Malolos Convention)". Arellano Law Foundation: The LawPhil Project.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "1899 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines (Malolos Convention)". Corpus Juris Philippine Law Library.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Agoncillo, Teodoro C. (1990) [1960]. History of the Filipino People (8th ed.). Quezon City: Garotech Publishing. ISBN 978-971-8711-06-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), ISBN 971-8711-06-6, ISBN 978-971-8711-06-4. - Arcilla, José S. (1994). An Introduction to Philippine History (Fourth ed.). Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-261-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), ISBN 971-550-261-X, ISBN 978-971-550-261-0. - Escalante, Rene R. (2007). The Bearer of Pax Americana: The Philippine Career of William H. Taft, 1900–1903. Quezon City, Philippines: New Day Publishers. ISBN 978-971-10-1166-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) ISBN 971-10-1166-2, ISBN 978-971-10-1166-6. - Guerrero, León María (1987). "The First Filipino, a Biography of José Rizal". National Heroes Commission.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Guevara, Sulpico, ed. (1972). "The Malolos Constitution (English translation)". The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Kalaw, Maximo M. (1927). "Appendix D, The Political Constitution of the Philippine Republic". The development of Philippine politics. Oriental commercial.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Penny, Ralph; Penny, Ralph John (2002). A history of the Spanish language (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-01184-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Quilis, Antonio; Casado-Fresnillo, Celia (2008). La lengua española en Filipinas: Historia, situación actual, el chabacano, antología de textos. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas; Instituto de Lengua, Literatura y Antropología; Anejos de la Revista de Filología Española. ISBN 978-84-00-08635-0.

- Rappa, Antonio L.; Wee, Lionel (2006). Language Policy and Modernity in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-4510-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), ISBN 1-4020-4510-7, ISBN 978-1-4020-4510-3. - Rodriguez, Rufus Bautista (1997). "The 1899 'Malolos' Constitution". Constitutionalism in the Philippines: With Complete Texts of the 1987 Constitution and Other Previous Organic Acts and Constitutions. Rex Bookstore, Inc. p. 130. ISBN 978-971-23-2193-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), ISBN 971-23-2193-2, ISBN 978-971-23-2193-1. - Rodríguez-Ponga, Rafael. "Pero ¿cuántos hablan español en Filipinas?/But how many speak Spanish in the Philippines?" (PDF) (in Spanish).

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help). - Stevens, Joseph Earle (1898). "Yesterdays in the Philippines". Scribner.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Woods, Damon L. (2005). The Philippines: A Global Studies Handbook (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-675-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), ISBN 1-85109-675-2, ISBN 978-1-85109-675-6.

Further reading

- General

- Forbes, William Cameron (1945). "The Philippine Islands". Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help).

- Statistics

- Gómez Rivera, Guillermo. "Statistics: Spanish Language in the Philippines". Archived from the original on October 27, 2009.

- Gómez Rivera, Guillermo. "Estadística: El Idioma español en Filipinas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

- Language Situation

- Andrade Jr., Pío (2001). "Education and Spanish in the Philippines". Madrid, Spain: Asociación Cultural Galeón de Manila (galeondemanila.org). Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - Rodao, Florentino (1997). "Spanish language in the Philippines : 1900–1940". Philippine studies. 12. 45 (1). Manila, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press: 94–107. ISSN 0031-7837. OCLC 612174151. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010.

- Gómez Rivera, Guillermo. "El Idioma español en Filipinas: Año 2005" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on July 14, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Teaching of Spanish in the Philippines, UNESCO, February 1968

- List of Tagalog words of Spanish origin, self-published, tripod.com

- Semanario de Filipinas, Philippine Weekly news blog

- E-Dyario Filipinas, online newspaper

- Alas Filipinas, the first and only Spanish blog in the Philippines

- Revista Filipina, online magazine

- Cohen, Margot. Filipinos Learning Not to Scorn Spanish. Yale Center for the Study of Globalization, Yale University. April 2010.

- Asociacion Cultural Galeon de Manila, Spanish-Philippine cultural research group based in Madrid (in Spanish and English).

- Círculo Hispano-Filipino (in Spanish and English)

- Website of Kaibigan Kastila

- Spanish Made Easy and Practical For Filipinos

- Spanish Program for Cultural Cooperation

- Casino Español de Manila

- Casino Español de Cebú

- Instituto Cervantes de Manila

- Documentary "El Idioma Español en Filipinas" (Spanish)

- Spanish Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines