Speculum Maius

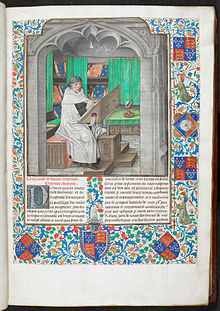

Strasbourg: Johann Mentelin 1473, Speculum historiale | |

| Author | Vincent of Beauvais |

|---|---|

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Encyclopedia |

The Speculum maius or "Greater Mirror" was a major encyclopedia of the Middle Ages written by Vincent of Beauvais in the 13th century. It was a great compendium of all knowledge of the time. The work seems to have consisted of three parts: the Speculum Naturale, Speculum Doctrinale and Speculum Historiale. However, all the printed editions include a fourth part, the Speculum Morale, added in the 14th century and mainly compiled from Thomas Aquinas, Stephen of Bourbon, and a few other contemporary writers.[1][2]

Compilation[edit]

Vincent de Beauvais worked on his compendium the Great Mirror for approximately 29 years (1235-1264)[3][4] in the pursuit of presenting a compendium of all of the knowledge available at the time. He collected the materials for the work from Île-de-France libraries, and there is evidence to suggest even further than that.[5] He found support for the creation of the Great Mirror from the Dominican order to which he belonged as well as King Louis IX of France.[5] The metaphor of the title has been argued to "reflect" the microcosmic relations of Medieval knowledge. In this case, the book mirrors "both the contents and organization of the cosmos".[6] Vincent himself stated that he chose "Speculum" for its name because his work contains "whatever is worthy of contemplation (speculatio), that is, admiration or imitation."[7] It is by this name that the compendium is connected to the medieval genre of speculum literature.

Content[edit]

The original structure of the work consisted of three parts: the Mirror of Nature (Speculum Naturale), Mirror of Doctrine (Speculum Doctrinale) and Mirror of History (Speculum Historiale). A fourth part, the Speculum Morale, was initiated by Vincent but there are no records of its contents. All the printed editions of the Great Mirror include this fourth part, which is mainly compiled from Thomas Aquinas, Stephen de Bourbon, and a few other contemporary writers[2] by anonymous fourteenth century Dominicans.[8] As a whole, the work totals 3.25 million words[9] and 80 books and 9885 chapters.[10] Additionally it is ordered "according to the order of sacred Scripture," utilizing the sequence of Genesis to Revelation,[11] from "creation, to fall, redemption, and re-creation".[12] This ordering system provides evidence that this "thirteenth-century encyclopedia must be counted among the tools for biblical exegesis".[11] In this vein, the Mirror of Nature has connections to the hexameron genre of texts that are commentaries on the six days of creation.[13] Additional generic connections come from Hélinand of Froidmont chronicle and Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae. Isidore's influence is explicitly referenced by Vincent's prologue and can be seen in some minor forms of organization as well as the stylistic brevity used to describe the branches of knowledge.[14]

Mirror of Nature (Speculum Naturale)[edit]

The vast tome of the Mirror of Nature, divided into thirty-two books and 3,718 chapters, is a summary of all of the science and natural history known to Western Europe towards the middle of the 13th century, a mosaic of quotations from Latin, Greek, Arabic, and even Hebrew authors, with the sources given. Vincent distinguishes, however, his own remarks.[2] Vincent de Beauvais began work on the Mirror of Nature from around 1235 to around the time of his death in 1264.[4] During this period, it was first completed in 1244 and then expanded in a second version in 1259 or 1260.[15]

- Book i. opens with an account of the Trinity and its relation to creation; then follows a similar series of chapters about angels, their attributes, powers, orders, etc., down to such minute points such as their methods of communicating thought, on which matter the author decides, in his own person, that they have a kind of intelligible speech, and that with angels, to think and to speak are not the same process.[2]

- Book ii. treats of the created world, of light, color, the four elements, Lucifer and his fallen angels and the work of the first day.[2]

- Books iii. and iv. deal with the phenomena of the heavens and of time, which is measured by the motions of the heavenly bodies, with the sky and all its wonders, fire, rain, thunder, dew, winds, etc.[2]

- Books v.-xiv. treat of the sea and the dry land: the discourse of the seas, the ocean and the great rivers, agricultural operations, metals, precious stones, plants, herbs with their seeds, grains and juices, trees wild and cultivated, their fruits and their saps. Under each species, where possible, Vincent gives a chapter on its use in medicine, and he adopts for the most part an alphabetical arrangement. In book ix., he gives an early instance of the use of the magnet in navigation.[2]

- Book xv. deals with astronomy: the moon, the stars, the zodiac, the sun, the planets, the seasons and the calendar.[2]

- Books xvi. and xvii. treat of fowls and fishes, mainly in alphabetical order and with reference to their medical qualities.[2]

- Books xviii.-xxii. deal in a similar way with domesticated and wild animals, including the dog, serpents, bees and insects. Book xx also includes descriptions of fantastic hybrid creatures like the draconope, or "snake-foot", which are described as "powerful serpents, with faces very like those of human maidens and necks ending in serpent bodies".[16] There is also a general treatise on animal physiology spread over books xxi.-xxii.[2]

- Books xxiii.-xxviii. discuss the psychology, physiology and anatomy of man, the five senses and their organs, sleep, dreams, ecstasy, memory, reason, etc.

The remaining four books seem more or less supplementary; the last (xxxii.) is a summary of geography and history down to the year 1250, when the book seems to have been given to the world, perhaps along with the Speculum Historiale and possibly an earlier form of the Speculum Doctrinale.[2]

Mirror of Doctrine (Speculum Doctrinale)[edit]

The second part, Mirror of Doctrine, in seventeen books and 2,374 chapters, is intended to be a practical manual for the student and the official alike; and, to fulfil this object, it treats of the mechanic arts of life as well as the subtleties of the scholar, the duties of the prince and the tactics of the general. It is a summary of all the scholastic knowledge of the age and does not confine itself to natural history. It treats of logic, rhetoric, poetry, geometry, astronomy, the human instincts and passions, education, the industrial and mechanical arts, anatomy, surgery and medicine, jurisprudence and the administration of justice.[2]

The first book, after defining philosophy, etc., gives a long Latin vocabulary of some 6,000 or 7,000 words. Grammar, logic, rhetoric and poetry are discussed in books ii. and iii., the latter including several well-known fables, such as the lion and the mouse. Book iv. treats of the virtues, each of which has two chapters of quotations allotted to it, one in prose and the other in verse. Book v. is of a somewhat similar nature. With book vi., we enter on the practical part of the work: it gives directions for building, gardening, sowing and reaping, rearing cattle and tending vineyards; it includes also a kind of agricultural almanac for each month in the year.[2]

Books vii.-ix. have reference to the political arts: they contain rules for the education of a prince and a summary of the forms, terms and statutes of canonical, civil and criminal law. Book xi. is devoted to the mechanical arts, of weavers, smiths, armourers, merchants, hunters, and even the general and the sailor.[2]

Books xii.-xiv. deal with medicine both in practice and in theory: they contain practical rules for the preservation of health according to the four seasons of the year and treat of various diseases from fever to gout.[2]

Book xv. deals with physics and may be regarded as a summary of the Mirror of Nature. Book xvi. is given up to mathematics, under which head are included music, geometry, astronomy, astrology, weights and measures, and metaphysics. It is noteworthy that in this book, Vincent shows a knowledge of the Arabic numerals, though he does not call them by this name. With him, the unit is termed "digitus"; when multiplied by ten it becomes the "articulus"; while the combination of the articulus and the digitus is the "numerus compositus". In his chapter xvi. 9, he clearly explains how the value of a number increases tenfold with every place it is moved to the left. He is even acquainted with the later invention of the cifra, or cipher.[17]

The last book (xvii.) treats of theology or mythology, and winds up with an account of the Holy Scriptures and of the Fathers, from Ignatius of Antioch and Dionysius the Areopagite to Jerome and Gregory the Great, and even of later writers from Isidore and Bede, through Alcuin, Lanfranc and Anselm of Canterbury, down to Bernard of Clairvaux and the brethren of St Victor.[10]

Mirror of History (Speculum Historiale)[edit]

The most widely disseminated part of the Great Mirror was the Mirror of History, which provided a history of the world down to Vincent's time. It was a massive work, running to nearly 1400 large double-column pages in the 1627 printing.[10] While it has been suggested that the Chronicon of Helinand of Froidmont (d. c. 1229) served as its model,[10] more recent research points out that the Mirror of History differs from Helinand's work because it did not use chronology as a primary system of organization.[18]

The first book opens with the mysteries of God and the angels, and then passes on to the works of the six days and the creation of man. It includes dissertations on the various vices and virtues, the different arts and sciences, and carries down the history of the world to the sojourn in Egypt.[10]

The next eleven books (ii.-xii.) conduct us through sacred and secular history down to the triumph of Christianity under Constantine. The story of Barlaam and Josaphat occupies a great part of book xv.; and book xvi. gives an account of Daniel's nine kingdoms, in which account Vincent differs from his professed authority, Sigebert of Gembloux, by reckoning England as the fourth instead of the fifth.[10]

In the chapters devoted to the origins of Britain, he relies on the Brutus legend, but cannot carry his catalogue of British or English kings further than 735, where he honestly confesses that his authorities fail him.[10]

Seven more books bring the history to the rise of Muhammad (xxiii.) and the days of Charlemagne (xxiv.). Vincent's Charlemagne is a curious medley of the great emperor of history and the champion of romance. He is at once the gigantic eater of Turpin, the huge warrior eight feet high, who could lift the armed knight standing on his open hand to a level with his head, the crusading conqueror of Jerusalem in the days before the crusades, and yet with all this the temperate drinker and admirer of St Augustine, as his character had filtered down through various channels from the historical pages of Einhard.[10]

Book xxv. includes the first crusade, and in the course of book xxix., which contains an account of the Tatars, the author enters on what is almost contemporary history, winding up in book xxxi. with a short narrative of the crusade of St Louis in 1250.[10]

One remarkable feature of the Mirror of History is Vincent's constant habit of devoting several chapters to selections from the writings of each great author, whether sacred or profane, as he mentions him in the course of his work. The extracts from Cicero and Ovid, Origen and St John Chrysostom, Augustine and Jerome are but specimens of a useful custom which reaches its culminating point in book xxviii., which is devoted entirely to the writings of St Bernard.[10]

An aspect of the Mirror of History is the large space devoted to miracles. Four of the medieval historians from whom he quotes most frequently are Sigebert of Gembloux, Hugh of Fleury, Helinand of Froidmont, and William of Malmesbury, whom he uses for Continental as well as for English history.[10]

Sources[edit]

The number of writers quoted by Vincent is substantial: in the Great Mirror alone no less than 350 distinct works are cited, and to these must be added at least 100 more for the other two Specula. His reading ranges from philosophers to naturalists including Peter Alphonso, Aristotle, Augustine,[16] Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā),[19] Julius Caesar (whom he calls Julius Celsus), Cicero,[20] Eusebius, Peter Helias,[21] the Didascalicon of Hugh of St. Victor,[22] Quintilian,[20] Seneca,[23] and Thomas Aquinas's Quaestiones disputatae de veritate.[24] Beauvais also extracted information from another encyclopedic text heavily referenced in the Middle Ages, Pliny the Elder's Natural History.[25] Additionally he seems to have known Hebrew, Arabic and Greek authors only through their popular Latin versions. He admits that his quotations are not always exact, but asserts that this was the fault of careless copyists.[10]

Reception history[edit]

Manuscript copies[edit]

Researchers have accounted for approximately 250–350 different manuscript copies of the Great Mirror in varying degrees of completion.[26] This is due to the fact that the Great Mirror was rarely copied in full, with the possibility of only two sets of a tripartie copy surviving today.[27] This means that circulation of the four parts varied while the Mirror of History was by far the most popular part to be copied within Europe.[27] Beyond the labour involved in copying manuscripts, one historian has argued that such separation of the Great Mirror was due in part to medieval readers not recognizing the work to be organized as a whole.[27]

Printed editions[edit]

With the advent of moveable type, the Great Mirror saw renewed interest since it was easier to reproduce such a sizeable work. Accordingly, there were five editions of the Great Mirror printed between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries.[28]

The inclusion of the Speculum Morale[edit]

The four-volume complete edition Speculum quadruplex (with the speculum morale) was printed in Douai by Balthazar Bellerus in 1624 and was reprinted in 1964/65 in Graz. Printed editions of the Great Mirror often include a fourth section called the Speculum Morale. While Beauvais had plans to write this book there is no historical record of its content. However, after 1300 a compilation was created and attributed to be part of the Great Mirror.[29] An eighteenth century writer remarked that this work was "a more-or-less worthless farrago of a clumsy plagiarist", one who merely extracted and compiled great swaths of text from other authors.[30] A textual analysis of how the Speculum Morale integrated St. Thomas Aquinas's Summa theologiae shows that, while heavily extracted, the compiler made conscious decisions about the placement of parts and also redirected the meaning of certain passages.[31]

References[edit]

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Archer, Thomas Andrew (1911). "Vincent of Beauvais". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–91, see page 90.

The Speculum Majus....The Speculum Naturale.....The Speculum Doctrinale... the Speculum Historiale...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Archer 1911, p. 90.

- ^ Franklin-Brown, Mary (2012). Reading the World: Encyclopedic Writing in the Scholastic Age. Chicago, MI, USA: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226260686.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 11.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 95.

- ^ Harris-McCoy, Daniel (2008). Varieties of encyclopedism in the early Roman Empire: Vitruvius, Pliny the Elder, Artemidorus (Ph.D). University of Pennsylvania. p. 116. ProQuest 304510158.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 271.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 98.

- ^ Guerry, Emily (2014). "Review of 'Memory and Commemoration in Medieval Culture'". Reviews in History. doi:10.14296/rih/2014/1601.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Archer 1911, p. 91.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 97.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 106–107.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 100–101.

- ^ Vincent de Beauvais @ Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (ARLIMA.net). Likewise reported in the book Schooling and Society: The Ordering and Reordering of Knowledge in the Western Middle Ages, year 2004 on page 102.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 258.

- ^ Archer 1911, pp. 90, 91.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 224.

- ^ a b Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 229.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 42; 101.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 228.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 275.

- ^ Doody, Aude (2010). Pliny's encyclopedia : the reception of the Natural history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-511-67707-6.

- ^ Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 126.

- ^ a b c Franklin-Brown 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Guzman, Gregory (1974). "The Encyclopedist Vincent of Beauvais and His Mongol Extracts from John of Plano Carpini and Simon of Saint-Quentin". Speculum. 49 (2): 287–307. doi:10.2307/2856045. JSTOR 2856045. S2CID 162460524.

- ^ Zahora, Tomas; Nikulin, Dmitri; Mews, Constant J.; Squire, David (2015). "Deconstructing Bricolage: Interactive Online Analysis of Compiled Texts with Factotum". Digital Humanities Quarterly. 9 (1): paragraph 12. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ Zahora et al. 2015, p. paragraph 13.

- ^ Zahora et al. 2015, p. paragraph 23.

External links[edit]

- Speculum naturale (Google Books), Hermannus Liechtenstein, 1494.

- Speculum Historiale. XI-XVI. Naples, before 1481.

- Speculum Historiale. XVII-XXI. Naples, before 1481.

- Speculum Historiale. XXVI-XXIX. Naples, before 1481.