Subject–verb inversion in English

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Subject–verb inversion in English is a type of inversion marked by a predicate verb that precedes a corresponding subject, e.g., "Beside the bed stood a lamp". Subject–verb inversion is distinct from subject–auxiliary inversion because the verb involved is not an auxiliary verb.[citation needed]

Overview[edit]

The following sentences illustrate subject–verb inversion. They compare canonical order with the non-standard inversion order, and they demonstrate that subject–verb inversion is unlikely if the subject is a weak (non-stressed) definite pronoun:

- a. Jim sat under the tree.

- b. Under the tree sat Jim. - Subject–verb inversion

- c. *Under the tree sat he. - Subject–verb inversion unlikely with weak definite subject pronoun

- a. The dog came down the stairs.

- b. Down the stairs came the dog. - Subject–verb inversion

- c. *Down the stairs came it. - Subject–verb inversion unlikely with weak definite subject pronoun

- a. Some flowers are in the vase.

- b. In the vase are some flowers. - Subject–verb inversion with the copula

- c. *In the vase are they. - Subject–verb inversion unlikely with weak definite subject pronoun

- a. Bill said, "I am hungry."

- b. "I am hungry," said Bill. - Subject–verb–object inversion

- c. "I am hungry," said he. - Subject–verb–object inversion here possible, but less likely, with weak definite subject pronoun

Subject–verb inversion has occurred in the b-sentences to emphasize the post-verb subject. The emphasis may occur, for instance, to establish a contrast of the subject with another entity in the discourse context.

Types of subject–verb inversion[edit]

A number of types of subject–verb inversion can be acknowledged based upon the nature of phrase that precede the verb and the nature of the verb(s) involved. The following subsections enumerate four distinct types of subject–verb inversion: locative inversion, directive inversion, copular inversion, and quotative inversion.

Locative inversion[edit]

Locative inversion also occurs in many languages, including Brazilian Portuguese, Mandarin Chinese, Otjiherero, Chichewa, and a number of Germanic and Bantu languages. A predicative phrase is switched from its default postverbal position to a position preceding the verb, which causes the subject and the finite verb to invert. For example:[1]

- a. A lamp lay in the corner.

- b. In the corner lay a lamp. – Locative inversion

- c. *In the corner lay it. – Locative inversion unlikely with a weak pronoun subject

- a. Only Larry sleeps under that tree.

- b. Under that tree sleeps only Larry. – Locative inversion

- c. *Under that tree sleeps he. – Locative inversion unlikely with a weak pronoun subject

The fronted expression that evokes locative inversion is an adjunct of location. Locative inversion in modern English is a vestige of the V2 order associated with earlier stages of the language.

Directive inversion[edit]

Directive inversion is closely related to locative inversion insofar as the pre-verb expression denotes a location, the only difference being that the verb is now a verb of movement. Typical verbs that allow directive inversion in English are come, go, run, etc.[2]

- a. Two students came into the room.

- b. Into the room came two students. – Directive inversion

- c. *Into the room came they. – Directive inversion unlikely with a weak pronoun subject

- a. The squirrel fell out of the tree.

- b. Out of the tree fell the squirrel. – Directive inversion

- c. *Out of the tree fell it. – Directive inversion unlikely with a weak pronoun subject

The fronted expression that evokes inversion is a directive expression; it helps express movement toward a destination. The following sentence may also be an instance of directive inversion, although the fronted expression expresses time rather than direction:

- a. The toasts came after the speeches.

- b. After the speeches came the toasts. – Inversion after a time expression

Like locative inversion, directive inversion is undoubtedly a vestige of the V2 word order associated with earlier stages of the language.

Copular inversion[edit]

Copular inversion occurs when a predicative nominal switches positions with the subject in a clause where the copula be is the finite verb. The result of this inversion is known as an inverse copular construction, e.g.[3]

- a. Bill is our representative.

- b. Our representative is Bill. – Copular inversion

- c. *Our representative is he. – Copular inversion unlikely with weak pronoun subject

- a. The objection was a concern.

- b. A concern was the objection. – Copular inversion

- c. *A concern was it. – Copular inversion unlikely with weak pronoun subject

This type of inversion occurs with a finite form of the copula be. Since English predominantly has SV order, it will tend to view whichever noun phrase immediately precedes the finite verb as the subject. Thus in the second b-sentence, A concern is taken as the subject, and the objection as the predicate. But if one acknowledges that copular inversion has occurred, one can argue that the objection is the subject; and A concern, the predicate. This confusion has led to focused study of these types of copular clauses.[4] Where there is a difference in number, the verb agrees with the noun phrase that precedes it:

- a. Jack and Jill are the problem.

- b. The problem is Jack and Jill. – On an inversion analysis, the verb agrees with the apparent predicate.

Quotative inversion[edit]

In literature, subject–verb inversion occurs with verbs that attribute speech to a character. The inversion follows an instance of direct speech that typically occurs in quotation marks:[5]

- a. "We are going to win," Bill said.

- b. "We are going to win," said Bill. – Quotative inversion

- c. *"We are going to win," said he. – Quotative inversion less likely with weak subject pronoun

- a. "What was the problem?" Larry asked.

- b. "What was the problem?" asked Larry. – Quotative inversion

- c. *"What was the problem?" asked he. – Quotative inversion less likely with weak subject pronoun

This sort of inversion is almost entirely absent from everyday speech. It occurs almost exclusively in literary contexts.

Multiple verbs[edit]

Subject–verb inversion can sometimes involve more than one verb. In these cases, the subject follows all of the verbs, the finite as well as non-finite ones, e.g.

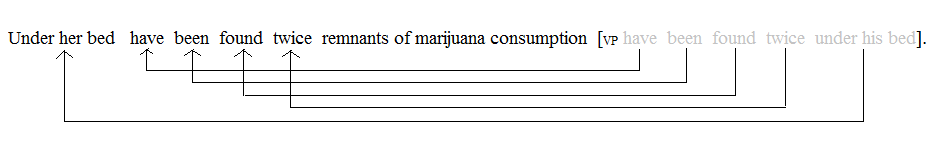

- a. Remnants of marijuana consumption have been found under her bed twice.

- b. Under her bed have been found remnants of marijuana consumption twice.

- c. Under her bed have been found twice remnants of marijuana consumption.

Sentence b and sentence c, where the subject follows all the verbs, stand in stark contrast to what occurs in cases of subject–auxiliary inversion, which have the subject appearing between the finite auxiliary verb and the non-finite verb(s), e.g.

- d. Has anything been found under her bed?

Further, the flexibility across sentence b and sentence c demonstrates that there is some freedom of word order in the post-verb domain. This freedom is consistent with an analysis in terms of rightwards shifting of the subject, where heavier constituents tend to follow lighter ones. Evidence for this claim comes from the observation that equivalents of sentence c above are not as good with a light subject:

- e. ?? Under her bed has been found twice marijuana.

- f. * Under her bed has been found twice it.

These facts clearly distinguish this kind of inversion from simple subject–auxiliary inversion, which applies regardless of the weight of the subject:

- g. Has it been found under her bed?

Thus, it is not clear from these examples if subject–auxiliary inversion is a unified grammatical phenomenon with the other cases discussed above.

Structural analysis[edit]

Like most types of inversion, subject–verb inversion is a phenomenon that challenges theories of sentence structure. In particular, the traditional subject–predicate division of the clause (S → NP VP) is difficult to maintain in light of instances of subject–verb inversion such as Into the room will come a unicorn. Such sentences are more consistent with a theory that takes sentence structure to be relatively flat, lacking a finite verb phrase constituent, i.e. lacking the VP of S → NP VP.

In order to maintain the traditional subject–predicate division, one has to assume movement (or copying) on a massive scale. The basic difficulty is suggested by the following trees representing the phrase structures of the sentences:

The convention is used here where the words themselves appear as the labels on the nodes in the trees. The tree on the left shows the canonical analysis of the clause, whereby the sentence is divided into two immediate constituents, the subject Bill and the finite VP crouched in the bush. To maintain the integrity of the finite VP constituent crouched in the bush, one can assume a rearranging of the constituents in the second sentence on the right, whereby both crouched and in the bush move out of the VP and up the structure. The account suggested with the second tree is the sort of analysis that one is likely to find in Government and Binding Theory or the Minimalist Program. It is a phrase structure account that relies on unseen movement/copying mechanisms below the surface.

The unseen mechanisms must perform an even greater job for the marijuana-example above. That sentence (sentence c in the previous section) would necessitate at least five instances of movement/copying in order to maintain the presence of an underlying finite VP constituent.

This makes it unlikely that the mechanism discussed above is the correct analysis for the marijuana-examples, as these might be generated by the same mechanisms that underlie extraposition and heavy-NP shift.

An alternative analysis of subject–verb inversion rejects the existence of the finite VP constituent. Due to the absence of this constituent, the structure is flatter, which simplifies matters considerably. The sentences with inverted order will often not result in a discontinuity, which means the basic hierarchy of constituents (the vertical order) does not change across the canonical and inverted variants. The following trees illustrate this alternative account. The first two trees illustrate the analysis in an unorthodox phrase structure grammar that rejects the presence of the finite VP constituent, and the second two trees illustrate the analysis in a dependency grammar. Dependency grammar rejects the presence of a finite VP constituent.[6]

Because there is no finite VP constituent in these trees, the basic hierarchy of constituents remains consistent. What changes is just the linear order of the constituents. The following trees illustrates the "flat" dependency-based analysis of the marijuana-example.

Due to the lack of a finite VP constituent, the basic hierarchy of constituents is not altered by inversion. However, this analysis does not capture the obvious dependency between the main verb and the inverted subject.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ For more examples and discussions of locative inversion, see Quirk et al. (1979:478), Culicover (1997:170f.) and Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:409).

- ^ For further examples of directive inversion, see Quirk et al. (1979:478), Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:410), and Downing and Locke (1992:231).

- ^ For further examples and discussion of copular inversion, see Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:409).

- ^ Moro (1997) and Mikkelsen (2005) are two examples of detailed studies of copular inversion.

- ^ For more examples of quotative inversion, see for instance Greenbaum and Quirk (1990:410f.) and Downing and Locke (1992:300f.).

- ^ Concerning the dependency grammar rejection of a finite VP constituent, see Tesnière (1959:103–105), Matthews (2007:17ff.), Miller (2011:54ff.), and Osborne et al. (2011:323f.).

Literature[edit]

- Culicover, P. 1997. Principles and parameters: An introduction to syntactic theory. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Downing, A. and Locke, P. 1992. English grammar: A university course, second edition. London: Routledge.

- Greenbaum, S. and R. Quirk. 1990. A student's grammar of the English language. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman.

- Groß, T. and T. Osborne 2009. Toward a practical dependency grammar theory of discontinuities. SKY Journal of Linguistics 22, 43-90.

- Matthews, P. H. (2007). Syntactic Relations: a critical survey (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521608299. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- Mikkelsen, Line 2005. Copular clauses: Specification, predication, and equation. Linguistics Today 85. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Miller, J. 2011. A critical introduction to syntax. London: continuum.

- Moro, A. 1997. The raising of predicates: Predicative noun phrases and the theory of clause structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Osborne, T., M. Putnam, and T. Groß 2011. Bare phrase structure, label-less trees, and specifier-less syntax: Is Minimalism becoming a dependency grammar? The Linguistic Review 28, 315–364.

- Quirk, R. S. Greenbaum, G. Leech, and J. Svartvik. 1979. A grammar of contemporary English. London: Longman.

- Tesnière, L. 1959. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Tesnière, L. 1969. Éleménts de syntaxe structurale, 2nd edition. Paris: Klincksieck.