Surf's Up (song)

| "Surf's Up" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by the Beach Boys | ||||

| from the album Surf's Up | ||||

| B-side | "Don't Go Near the Water" | |||

| Released | November 29, 1971 | |||

| Recorded | November 4, 1966 – July 1971 | |||

| Studio | Western, Columbia, and Beach Boys Studio, Los Angeles | |||

| Genre | Progressive pop[1] | |||

| Length | 4:11 | |||

| Label | Brother, Reprise | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Brian Wilson, Van Dyke Parks | |||

| Producer(s) | The Beach Boys | |||

| The Beach Boys singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Music video | ||||

| "Surf's Up" on YouTube | ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

"Surf's Up" is a song recorded by the American rock band the Beach Boys that was written by Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks. It was originally intended for Smile, an unfinished Beach Boys album that was scrapped in 1967. The song was later completed by Brian and Carl Wilson as the closing track of the band's 1971 album Surf's Up.

Nothing in the song relates to surfing; the title is a play-on-words referring to the group shedding their image. The lyrics describe a man at a concert hall who experiences a spiritual awakening and resigns himself to God and the joy of enlightenment, the latter envisioned as a children's song. Musically, the song was composed as a two-movement piece that modulates key several times and avoids conventional harmonic resolution. It features a coda based on another Smile track, "Child Is Father of the Man".

The only surviving full-band recording of "Surf's Up" from the 1960s is the basic backing track of the first movement. There are three known recordings of Wilson performing the full song by himself, two of which were filmed for the 1967 documentary Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, where it was described as "too complex" to comprehend on a first listen. Several years after Smile was scrapped, the band added new vocals and synthesizer overdubs to Wilson's first piano performance as well as the original backing track. Another recording from 1967 was found decades later and released for the 2011 compilation The Smile Sessions.

"Surf's Up" failed to chart when issued as a single in November 1971 with the B-side "Don't Go Near the Water". In 2004, Wilson rerecorded it for his solo version of Smile with new string orchestrations that he had originally intended to include in the piece. Pitchfork later included the song in separate rankings of the 200 finest songs of the 1960s and 1970s, and in 2011, Mojo staff members voted it the greatest Beach Boys song. As of 2020[update], it is listed among the 800-most highest rated songs of all time on Acclaimed Music.

Background and composition

"Surf's Up" was the second song Brian Wilson and Van Dyke Parks wrote together.[2] It was composed as a two-movement piece, most of it in one night while they were high on Wilson's Desbutols, and originally intended for the Beach Boys' album Smile.[3] In a self-penned 1969 article, former band associate Michael Vosse wrote that "Surf's Up" was to be the album's closing track, and that the song would have been followed by an "choral amen sort of thing."[4] Biographer Byron Preiss wrote that the song was envisioned as part of "The Elements" and was "briefly considered" to be paired with "Love to Say Dada".[5]

According to Parks, the song did not have a title until after the touring members of the band returned from a November 1966 tour of Britain. He said he had witnessed Dennis Wilson complaining that the group's British audiences had ridiculed them for their striped-shirt stage outfits, which inspired him to write the last lines of the song and suggest to Brian that the piece be titled "Surf's Up".[3] Brian remembered that when Parks made the suggestion, he felt it was "wild because surfing isn't related to the song at all."[2] However, AFM track sheets indicate that the song had already received its title before the group returned from their UK tour.[6]

There is a weak sense of tonal stability throughout the piece; musicologist Philip Lambert's analysis indicates that the composition may contain up to seven key modulations.[7] Wilson commented that the first chord was a minor seventh, "unlike most of our songs, which open on a major – and from there it just started building and rambling".[2] The beginning of the song alternates between the chords Gm7/D and Dm7/G, followed by F/C and other chords that suggest a key of F major, but ultimately ends at D/A.[8] Lambert was unable to determine if the section ends in the key of F, G, or D.[7] During one bar, the horn players perform a melodic phrase that replicates the laugh of the cartoon character Woody Woodpecker.[9]

The second movement largely consists of a solo piano and vocal performance by Wilson.[10] Its key suggests E-flat major in the beginning, then traverses to F major before returning to E-flat major and settling at C minor.[7] This part was originally intended to feature a more elaborate arrangement. When asked what he had remembered of the song's second movement in 2003, Wilson responded that it was supposed to feature a string ensemble.[11] In his 2016 memoir, it was written that he was unable to finish the song in the 1960s because it was "too rhapsodic" and "all over the place".[12]

Lyrics

Lyrics in "Surf's Up" reference artifacts of the patrician period, such as diamond necklaces, opera glasses, and horse-drawn carriages.[13] They also espouse themes related to childhood and God, similar to other songs written for Smile ("Wonderful" and "Child Is Father of the Man").[14] The title is a play-on-words referring to the group shedding their image. In surfing, "surf's up" means that the conditions of the waves are good, but when the phrase arrives in the song, it is used to conjure an image of a tidal wave.[15]

In Jules Siegel's October 1967 memoir for Cheetah magazine, "Goodbye Surfing, Hello God", he quoted Wilson offering a lengthy explanation of the album's lyrics. Reportedly, the song is about "a man at a concert" that is overtaken by music. "Columnated ruins domino" symbolizes the collapse of "empires", "ideas", "lives", and "institutions". After the lyric "canvas the town and brush the backdrop", the song's protagonist sets "off on his vision, on a trip". He then suffers a "choke of grief" at "his own suffering and the emptiness of life". At the end, he finds hope and returns "to the tides, to the beach, to childhood" before experiencing "the joy of enlightenment, of seeing God", which manifests in a children's song. Wilson concluded his summary, "Of course that's a very intellectual explanation. But maybe sometimes you have to do an intellectual thing."[16]

When I was in their picture everything was whirling in a big flux. "Wilder women!" we were calling. "Madder wine!" And I came up with that title, it was so simple, in the context of the excitement it seemed obvious: "Surf's Up."

Singer-songwriter Jimmy Webb interpreted the song as "a premonition of what was going to happen to our generation and ... to our music—that some great tragedy that we could absolutely not imagine was about to befall our world."[18] Academic Larry Starr wrote, "Van Dyke Parks’s poetic and allusive lyrics articulate the progression from a condition of disillusionment with a decadent and materialistic culture to the glimpse of a possibility for hope and renewal. This is all conveyed via an abundance of musical references and imagery."[19] Lambert said that the song prophesies an optimism for those who can capture the innocence of youth.[20] In the view of journalist Domenic Priore, the song was "a plea for the establishment to consider the wisdom coming out of youth culture in 1966."[2]

Starr further described it as "a very serious song, with an underlying somber tone for much of its duration that is leavened by wordplay ... and the near-miraculous turn toward hope as it ends. Its dark atmosphere is perhaps its greatest deviation, among many, from the features typical of the Beach Boys’ work".[19] Journalist Paul Williams interpreted the song as partly a commentary on the band's musical legacy, writing that the moment in which Wilson sings the line "surf's up" is "a pivot on which everything that's come before in the song wheels and turns, and maybe ... everything the Beach Boys and Brian have sung and played and done up to this moment."[21]

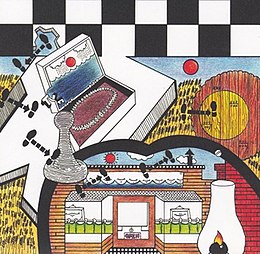

Artwork

Artist Frank Holmes, who designed the Smile cover artwork, created two illustrations that were inspired by the song's lyrics, "Diamond necklace play the pawn" and "Two-step to lamp's light". Along with several other drawings, they were planned to be included within a booklet packaged with the Smile LP.[22] In 2005, Holmes shared a background summary of his design choices:

"Diamond necklace play the pawn"

The diamond necklace is an open box, like a jewellery case, with a diamond necklace in it. There's a little lettering there, "Tif", which is a reference to Tiffany's.

"Play the pawn" is a chess expression — it's what you do when you can't think of anything else to do, so you push the pawn — so there's chess pieces in there. The footsteps are just random things popped around there.

This one is a composite of several different ideas: it has the Smile Shoppe there, without the people, and then the lamp, and the wheat field in the background. Then thee's the rain cloud, and the sun and the ocean, the Tiffany box, and the lamp in the lower right corner.[2]

"Two-step to lamp's light"

This quote is like a double entendre, with a two-step being an infinity to step to the light. The two-step — the dance — and "two-step to lamp's light" is an idea of stepping to enlightenment, finding your way there.

"Surf's Up" was, like, the inside wave and the outside wave, so surf's up inside. I put it inside a dwelling, with the floor and the lamp — and the two-step part — in front.

Some of these ideas came from my childhood. At Catholic school, the art classes would always be centred around the holidays. At Thanksgiving, we'd always get to draw the turkey and the Indians and the pilgrims — the feathers — so a lot of those things come from my childhood, ways of relating to the Americana concept for manifest destiny and the West as a basis for the Smile album.[2]

Recording

"1st Movement" and missing tapes

Wilson held the first tracking session for "Surf's Up" at Western Studio 3, with usual engineer Chuck Britz, on November 4, 1966. It was logged with the subtitle "1st Movement".[23] Musicians present were upright bassist Jimmy Bond, drummer Frank Capp, guitarist Al Casey, pianist Al De Lory, bassist Carol Kaye, and percussionist Nick Pellico.[24] Wilson instructed Capp to play jewelry sounds from what was possibly a ring of car keys.[25] Between November 7 and 8, overdubs were recorded with Capp, Pellico, and a horn ensemble consisting of Arthur Brieglab, Roy Caton, David Duke, George Hyde, and Claude Sherry.[6] The November 7 session was dedicated to experimenting with horn effects, including an exercise in which Wilson instructed his musicians to laugh and have conversations through their instruments. The tape of this experiment was later given the label "George Fell into His French Horn".[24] Journalist Rob Chapman compared the piece to experiments heard on the 1965 album The Heliocentric Worlds of Sun Ra, Volume One (1965).[9]

A fully-developed recording of the song's second movement has never been found. In 2004, Darian Sahanaja said that a tape for the instrumental tracking of the section was rumored to exist somewhere, while Mark Linett stated, "If it does exist, we haven't found it."[11] Asked decades after the fact, Wilson responded that he did not think that he ever recorded it.[26] As of 2020, there are at least two known "Surf's Up" recordings that have been presumed missing or lost: a vocal session at Columbia Studio from December 15, 1966, and two sessions at Western from January 23, 1967.[27][28] According to Badman, the December 15 session included vocal and piano overdubs onto the first movement backing track, as well as further recording on the song "Wonderful".[29] Siegel later claimed that the session "went very badly".[30]

The January 23 session featured additional instrumental tracking, including a 16-piece string and horn section overdubbed onto the bounced tape of the backing track from December 15.[31] In 2011, Linett commented, "It’s interesting because there’s a session sheet indicating that the second half of 'Surf’s Up' – the backing track was recorded. But there's never been any taped evidence of it, and obviously there was no taped evidence when the Beach Boys went to finish it in the Seventies. And nobody, including Brian, can confirm that it ever happened. So it may have been a session that was mislabeled, or a session that got canceled."[32]

Solo piano performances and Inside Pop filming

On the evening of December 15, 1966, Wilson was filmed at Columbia Studio singing and performing "Surf's Up" on piano for use in David Oppenheim's CBS-commissioned documentary Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution.[6] Wilson and Oppenheim were dissatisfied with the footage, and decided to reshoot the sequence at Wilson's home on December 17. His performance that day, executed in one take with a candelabrum placed on his grand piano, was captured by three film cameras and deemed satisfactory for use in the documentary.[34]

On May 6, 1967, days after stating that Smile was finished and ready to be released, band publicist Derek Taylor announced in his weekly column for Disc & Music Echo that the album had been "scrapped" by Wilson.[35] In late 1967, Wilson recorded several takes of another piano-vocal performance of "Surf's Up" at his home studio during sessions for the album Wild Honey. The forgotten demo was rediscovered several decades later when archivists searched through the contents at the end of the multi-track reel for the song "Country Air". Mark Linett stated: "No explanation for why he [Brian] did that and it was never taken any farther. Although I don’t think the intention was to take it any farther because it's just him singing live and playing piano."[32]

Surf's Up sessions

The recording sessions for the band's second album for Reprise Records, tentatively titled Landlocked, initially concluded in April 1971.[36] Band manager Jack Rieley had asked Brian about including "Surf's Up" on the record, and in early June, Brian suddenly gave approval for Carl and Rieley to finish the song.[37] While on a drive to meet record company executive Mo Ostin, Brian said to Rieley: "Well, OK, if you're going to force me, I'll ... put 'Surf's Up' on the album." Rieley asked, "Are you really going to do it?" to which Brian repeated, "Well, if you're going to force me."[37] According to Rieley: "We got into Warner Brothers and, with no coaxing at all, Brian said to Mo, 'I'm going to put 'Surf's Up' on the next album.'"[37]

From mid-June to early July, Carl and Rieley retrieved the Smile multi-tracks from Capitol's vaults, primarily to locate the "Surf's Up" masters, and attempted to repair and splice the tapes. Brian joined them on at least two occasions.[38] Afterward, the band set to work on recording the song at their private studio, located within Brian's home.[39] Brian initially refused to participate in the recording of "Surf's Up" and insisted that Carl take the lead vocal.[40] The group attempted to rerecord the song from scratch. "But we scrapped it", Rieley later said, "because it didn't quite come up to the original."[41] In 2021, this discarded rerecording was released on the compilation Feel Flows.[42] An unsuccessful attempt was also made to mashup Brian's 1966 vocal to the instrumental track. According to Linett, a tape showcasing this effort still exists in the group's archives.[11][32]

Carl ultimately overdubbed a lead vocal onto the song's first part, the original backing track dating from November 1966, as well as backing vocals. Two organ overdubs were also recorded.[39] The second movement was composed of the December 15, 1966 solo piano performance by Brian,[38] augmented with vocal and Moog synthesizer overdubs.[43] Carl reworked the refrain from another unreleased Smile song, "Child Is Father of the Man", into the coda of "Surf's Up".[39] Bruce Johnston recalled, "We ended up doing vocals to sort of emulate ourselves without Brian Wilson, which was kind of silly."[44] Al Jardine sang the lead vocal on this section.[26] Rieley said, "we all got involved in [the final tag]. ... I'm on it [and] a guy who worked for us part-time, Bill DeSimone, is on it. He just sings 'Hey, hey.' But it is integral to the tag on the record. That was a lot of fun ...".[40] Writing in a 1996 online Q&A, he wrote that Brian had "stated clearly that it was his intent all along for Child to be the tag for Surfs Up."[45]

To the surprise and glee of his associates, Brian emerged near the end of the sessions to aid Carl and engineer Stephen Desper in the completion of the coda.[46] As Desper recalled, "Brian didn't want to work on 'Surf's Up'. But after three days of coaxing, and of him walking in and out of the studio, he was finally convinced to do a part."[40] A final lyric was then devised, "A children's song / Have you listened as they play? / Their song is love / And the children know the way".[40] Desper credited Brian with the line,[46] while Rieley credited himself.[45] With the song completed, Landlocked was given the new title of Surf's Up.[40] The occasion marked the last time the group reworked material that was originally written for Smile.[47]

Release and contemporary reception

Inside Pop premiere

Inside Pop: The Rock Revolution, hosted by composer Leonard Bernstein, premiered on the CBS network on April 25, 1967.[33] Wilson's segment in the documentary ultimately only featured him singing "Surf's Up" at his piano without any interview footage or references to Smile.[48] Oppenheim declared through voice-over that the song was "poetic, beautiful in its obscurity" and "one aspect of new things happening in pop music today. As such, it is a symbol of the change many of these young musicians see in our future."[25] He further described Wilson as "one of today's most important pop musicians."[33] According to Badman, Wilson's segment aroused "great expectations" for Smile,[33] while journalist Nick Kent wrote that Wilson was "freaked out" and "broke down" over the praise he was afforded in the documentary.[49]

I was there when he did "Surf's Up" for the CBS cameras. I was in the car with him — we smoked a joint before he went and did that; and afterwards, I said to him, "Why don't you just stop fucking around with this stuff, and just release that as a single now, like now! Don't wait for the album to do it." But he was afraid to do it.

After Smile was scrapped, Wilson neglected to include the song on the replacement album Smiley Smile (1967). He said that his decision to keep "Surf's Up" unreleased was one that "nearly broke up" the band.[51][nb 1] In a review of Smiley Smile for Cheetah, a critic bemoaned the album's absence of "Surf's Up", writing that the song is "better than anything that is on the album and would have provided the same emotional catharsis as that 'A Day in the Life' provides for Sgt. Pepper."[53]

During a 1970 interview, Wilson commented that the song was "too long to make it for me as a record, unless it were an album cut, which I guess it would have to be anyway. It's so far from a singles sound. It could never be a single."[54]

Album release

On August 30, 1971, "Surf's Up" was released as the closing track on the LP of the same name.[40] It was also issued as the album's third single in the US, in November, and failed to chart.[55] A major part of the album's success came from the inclusion of the title track,[56] although most listeners at the time were unaware that the song derived from a lost Beach Boys album.[47] The band incorporated "Surf's Up" into their live set at the time. Circus reported that, at one concert, the group performed the song as a closer "after numerous requests" from the audience.[57] In another concert review from the NME, Tony Stewart reported that the band said "Surf's Up" was "a most apt title, implying they had deserted the surfing days".[58]

Reviewing the Surf's Up album for Melody Maker, Richard Williams wrote that the title track, "had it been released back at Pepper-time ... might have kept many people from straying into the pastures of indulgence and may have forced them to focus back on truer values. I've rarely heard a more perfect, more complete piece of music. From first to last it flows and evolves from the almost lush decadence of the first verses to the childlike wonders and open-hearted joy of the final chorale."[59] Don Heckman wrote in The New York Times that the song "bears easy comparison with the best of The Beatles' Sgt. Pepper songs".[57]

Rolling Stone's Arthur Schmidt judged the song to have lived up to its legend, although its placement on the record gave "something of the effect of Brian saying: 'Oh yeah, that’s our new album, but hey, you wanna hear something we had left over around here?'"[60] He added that while it "would have more than given a run to anything on Sergeant Pepper", the song was "dazzling" to a fault.[60] Geoffrey Cannon of The Guardian opined that Parks' lyrics were "pretentious", but compared the song favorably to "You Still Believe in Me" and "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times" from Pet Sounds: "Its subtle shifts of pace and timing, and delicate harmony singing, put it in the top flight of Beach Boys' numbers."[61]

Legacy

Other releases and performances

In 1995, the Wondermints – a band that included Sahanaja as a member – performed a live cover of "Surf's Up" at the Morgan-Wixon Theater in Los Angeles with Wilson in the audience, who was then quoted saying "If I'd had these guys back in '66, I could've taken Smile on the road."[62] Wilson rerecorded the song as part of his 2004 album, Brian Wilson Presents Smile, with new string orchestrations arranged by himself, Parks, Sahanaja, and Paul Mertens.[11] For the 2011 compilation The Smile Sessions, Mark Linett created a new mix of the song that mashed up the 1966 backing track to the vocals from Brian's contemporaneous piano demo.[63]

In 2000, Radio City Music Hall held the All-Star Tribute to Brian Wilson, a concert that included a performance of "Surf's Up" by Jimmy Webb, David Crosby, and Vince Gill.[64] Gill had accepted the invitation to perform the song without having heard it before, expecting it to be in the style of the band's uptempo hits. He remembered his reaction to hearing the song for the first time:

I put it on and my eyes got really big. I said, "This is like a classical piece. This is deep. This is all the way over my head, I can't even touch the bottom here." [I told the organizer] "Dude, I don't know if I can cut this. It's got stupid range ... I walked off stage doing it that night ... and Brian was on the side of the stage, and I walked by him, and he shook my hand and goes, "That was really beautiful. We never did that song live because it was too hard." [laughs] I said, "Thanks a lot!"[65]

Love & Mercy, the 2014 biopic of Wilson's life, features a recreation of the Inside Pop performance with actor Paul Dano portraying Wilson. Dano told a Rolling Stone interviewer, "My second day of filming, I had to perform 'Surf’s Up' over and over. It remains one of the best days I’ve ever had a film set. ... but it's tough [to play]. I simplified a lot of the left hand work on the piano. Brian’s left-hand work is pretty complicated."[66]

Retrospective assessments

Writing in his book Inside the Music of Brian Wilson (2007), Philip Lambert named the song "the soul of Smile" and the "sum total of its creators' most profound artistic visions" with its "perfect marriage of an eloquent lyric with music of commensurate power and depth."[67] Musician Elvis Costello said that when he discovered a bootlegged tape of Wilson performing the song, "It was like hearing a tape of Mozart. It's just Brian and his piano and yet it's all there in that performance. The song already sounds complete."[9]

Record Collector's Jamie Atkins said it was "so far ahead of the work of their contemporaries that it is not entirely surprising Wilson found himself recoiling from its sophistication and majesty; the songwriting equivalent of scaling Everest, only to find yourself thinking, 'Well, what now?'"[56] Critic Dave Marsh was less favorable towards the song. Writing in The Rolling Stone Record Guide (1983), he bemoaned the hype that continued to surround Wilson and the Smile project throughout the 1970s and opined that "Surf's Up" "was far less forceful and arguably less innovative than Wilson's surf-era hits."[68]

In a 1995 radio interview, Wilson referred to his singing on the recording as an "atrocious" performance. He said, "I'm embarrassed. Totally embarrassed. That was a piece of shit. Vocally it was a piece of shit. I was the wrong singer for it in the first place. ... And in the second place, I don't know why I would ever let a record go out like that."[55] A few years later, he added that his vocal "was a little bit limited. It's not my favorite vocal I ever did, but it did have heart."[69] In a 1975 interview, Mike Love voiced appreciation of the song's musical form and content, which he believed went beyond what was normally expected of commercial pop music.[70]

Accolades and polls

As of 2020[update], "Surf's Up" is listed as the 744th highest rated song of all time on Acclaimed Music.[71]

- In 2006, Pitchfork ranked Wilson's solo piano performance of the song at number 134 in its list of "The 200 Best Songs of the 1960s".[72]

- In 2011, Mojo staff members voted it the greatest Beach Boys song. The song's entry stated, "Not so much timeless but a song out of time, Surf's Up is an elegy the richness and mystery of which only deepens with age."[73]

- In 2016, Pitchfork ranked the Surf's Up version at number 122 on its list of "The 200 Best Songs of the 1970s". Contributor Andy Beta stated, "'Surf's Up' bade farewell to the Beach Boys' outdated surf-boy personas, right there in the title; it was complex, impressionistic, and the crowning achievement of Wilson and lyricist Van Dyke Parks’ collaboration. The lyrics alight on Tennyson, Maupassant, and children’s songs; the coda of 'The child is the father of the man,' easily the most effervescent chorus the Boys ever harmonized on, is also a stunning quote of a William Wordsworth poem."[74]

Personnel

Per Mark Dillon[75] and Keith Badman.[6]

Musicians on November 1966 instrumental track

- Jimmy Bond – upright bass

- Arthur Brieglab – overdubbed French horn

- Roy Caton – overdubbed trumpet

- Frank Capp – "jewelry" percussion (possibly a ring of car keys)

- Al Casey – electric baritone guitar

- David Duke – overdubbed French horn

- Carol Kaye – Fender bass

- George Hyde – overdubbed French horn

- Al de Lory – upright piano

- Nick Pellico – glockenspiel

- Claude Sherry – overdubbed French horn

Additional musicians on 1971 track

- Bill DeSimone – backing vocals (outro)

- Mike Love – backing vocals

- Al Jardine – lead vocal (outro), backing vocals

- Jack Rieley – backing vocals

- Brian Wilson – lead vocal and piano (second-movement), backing vocals

- Carl Wilson – lead vocal (first-movement), backing vocals

- Marilyn Wilson – backing vocals

- unknown – Moog synthesizer

References

Note

Citations

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 242.

- ^ a b c d e f Priore 2005, p. [page needed].

- ^ a b Carlin 2006, p. 97.

- ^ Vosse, Michael (April 14, 1969). "Our Exagmination Round His Factification For Incamination of Work in Progress: Michael Vosse Talks About Smile". Fusion. Vol. 8.

- ^ Lambert 2007, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d Badman 2004, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b c Lambert 2007, p. 278.

- ^ Lambert 2016, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Chapman, Rob (February 2002). "The Legend of Smile". Mojo. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012.

- ^ Lambert 2016, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b c d Bell, Matt (October 2004). "The Resurrection of Brian Wilson's Smile". Sound on Sound. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- ^ Wilson & Greenman 2016, p. 210.

- ^ Dillon 2012, p. 143.

- ^ Zahl, David (November 16, 2011). "That Time The Beach Boys Made a Teenage Symphony to God". Mockingbird.

- ^ Dillon 2012, p. 144.

- ^ Siegel 1997, p. 62.

- ^ Nolan, Tom (October 28, 1971). "The Beach Boys: A California Saga". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Carter 2016, p. 187.

- ^ a b Lambert 2016, p. 253.

- ^ Lambert 2007, p. 277.

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 103.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 173.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 156.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 157.

- ^ a b Dillon 2012, p. 145.

- ^ a b Dillon 2012, p. 146.

- ^ Doe, Andrew G. "GIGS66". Bellagio 10452. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Doe, Andrew G. "GIGS67". Bellagio 10452. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 166.

- ^ Siegel 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Peters, Tony (October 17, 2011). "Show #120 - Mark Linett - part 2 - Beach Boys SMiLE Sessions (10/17/11)". Iconfetch. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Badman 2004, p. 182.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 167.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 185.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 289.

- ^ a b c Badman 2004, p. 291.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Badman 2004, pp. 293, 296.

- ^ a b c d e f Badman 2004, p. 296.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 292.

- ^ Legaspi, Althea. "The Beach Boys Detail Massive 1969-1971 Era Box Set, Share 'Big Sur'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 144.

- ^ a b Rieley, Jack (October 18, 1996). "Jack Rieley's comments & Surf's Up".

- ^ a b Carlin 2006, p. 163.

- ^ a b Lambert 2016, p. 257.

- ^ Sanchez 2014, p. 97.

- ^ Kent 2009, p. 37.

- ^ Heylin 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Highwater, Jamake (1968). Rock and Other Four Letter Words: Music of the Electric Generation. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-552-04334-6.

- ^ Robertson, Sandy (April 19, 1980). "The Beach Boys: The Life of Brian". Sounds.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 273.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 300.

- ^ a b Atkins, Jamie (July 2018). "Wake The World: The Beach Boys 1967-'73". Record Collector.

- ^ a b Badman 2004, p. 299.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 316.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 298.

- ^ a b Schmidt, Arthur (October 14, 1971). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey. "Feature: Out of the City". The Guardian (October 29, 1971). Guardian Media Group: 10.

- ^ Priore 2005, p. 156.

- ^ Dillon 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Wilson & Greenman 2016, pp. 5, 206.

- ^ Musicians Hall of Fame & Museum. "How Vince Gill was in Over His Head - Talking about Sting & Brian Wilson". YouTube (Video). Event occurs at 12:30.

- ^ Fear, David (September 13, 2014). "Heroes and Villains: 'Love & Mercy"s Paul Dano on Playing Brian Wilson". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Lambert 2007, p. 274.

- ^ Marsh & Swenson 1983, p. 31.

- ^ White, Timothy (2000). Sunflower/Surf's Up (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Cohen, Scott (January 1975). "Beach Boys: Mike Love, Carl Wilson Hang Ten On Surfin', Cruisin' And Harmonies". Circus Raves. p. 27.

- ^ "The Beach Boys Surf's Up". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved October 9, 2020.

- ^ "The 200 Best Songs of the 1960s". Pitchfork. August 18, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2020.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Beach Boys Songs". Mojo. June 2012.

- ^ Pitchfork Staff (August 22, 2016). "The 200 Best Songs of the 1970s". Pitchfork.

- ^ Dillon 2012, pp. 145–147.

Bibliography

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (July 25, 2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.

- Carter, Dale (2016). "Into the Mystic? The Undergrounding of Brian Wilson, 1964–1967". In Lambert, Philip (ed.). Good Vibrations: Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys in Critical Perspective. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11995-0.

- Dillon, Mark (2012). Fifty Sides of the Beach Boys: The Songs That Tell Their Story. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77090-198-8.

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys (1. Da Capo Press ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806479.

- Heylin, Clinton (2007). The Act You've Known for All These Years: A Year in the Life of Sgt. Pepper and Friend (1st ed.). Canongate. ISBN 978-1841959184.

- Kent, Nick (2009). "The Last Beach Movie Revisited: The Life of Brian Wilson". The Dark Stuff: Selected Writings on Rock Music. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780786730742.

- Lambert, Philip (2007). Inside the Music of Brian Wilson: the Songs, Sounds, and Influences of the Beach Boys' Founding Genius. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1876-0.

- Lambert, Philip, ed. (2016). Good Vibrations: Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys in Critical Perspective. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11995-0.

- Leaf, David (1978). The Beach Boys and the California Myth. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-14626-3.

- Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John (eds.) (1983). The New Rolling Stone Record Guide. New York, NY: Random House/Rolling Stone Press. ISBN 0-394-72107-1.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Priore, Domenic (2005). Smile: The Story of Brian Wilson's Lost Masterpiece. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1860746276.

- Sanchez, Luis (2014). The Beach Boys' Smile. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62356-956-3.

- Siegel, Jules (1997) [1967]. "The Religious Conversion of Brian Wilson: Goodbye Surfing, Hello God". In Abbott, Kingsley (ed.). Back to the Beach: A Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys Reader. Helter Skelter. pp. 51–63. ISBN 978-1-90092-402-3.

- Williams, Paul (2002). Back to the Miracle Factory (1st ed.). Forge. ISBN 9780765303523.

- Wilson, Brian; Greenman, Ben (2016). I Am Brian Wilson: A Memoir. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82307-7.

Further reading

- Sellars, Jeff, ed. (2015). God Only Knows: Faith, Hope, Love, and The Beach Boys. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4982-0767-6.