Thailand

15°24′N 101°18′E / 15.4°N 101.3°E

Kingdom of Thailand ราชอาณาจักรไทย (Thai) Ratcha-anachak Thai | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Phleng Chat Thai (English: "Thai National Anthem") | |

![Location of Thailand (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) – [Legend]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Location_Thailand_ASEAN.svg/250px-Location_Thailand_ASEAN.svg.png) | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Bangkok 13°45′N 100°29′E / 13.750°N 100.483°E |

| Official languages | Thai[1] |

| Spoken languages | |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Thai Siamese (archaic) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy under a military junta |

• Monarch | Maha Vajiralongkorn |

| Prayut Chan-o-cha | |

| Legislature | National Legislative Assembly (acting as National Assembly) |

| Formation | |

| 1238–1448 | |

| 1351–1767 | |

| 1768–1782 | |

| 6 April 1782 | |

| 24 June 1932 | |

| 6 April 2017 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 513,120 km2 (198,120 sq mi) (50th) |

• Water (%) | 0.4 (2,230 km2) |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 71,601,103[8][9] (20th) |

• 2010 census | 64,785,909[10] |

• Density | 132.1/km2 (342.1/sq mi) (88th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $1.310 trillion[11] |

• Per capita | $18,943[11] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $514.700 billion[12] |

• Per capita | $7,588[12] |

| Gini (2013) | 37.8[13] medium |

| HDI (2017) | high (83rd) |

| Currency | Baht (฿) (THB) |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (ICT) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +66 |

| ISO 3166 code | TH |

| Internet TLD | |

Template:Contains Thai text Thailand (/ˈtaɪlænd/ TY-land), officially the Kingdom of Thailand and formerly known as Siam, is a country at the center of the Southeast Asian Indochinese peninsula composed of 76 provinces. At 513,120 km2 (198,120 sq mi) and over 68 million people, Thailand is the world's 50th largest country by total area and the 21st-most-populous country. The capital and largest city is Bangkok, a special administrative area. Thailand is bordered to the north by Myanmar and Laos, to the east by Laos and Cambodia, to the south by the Gulf of Thailand and Malaysia, and to the west by the Andaman Sea and the southern extremity of Myanmar. Its maritime boundaries include Vietnam in the Gulf of Thailand to the southeast, and Indonesia and India on the Andaman Sea to the southwest. Although nominally a constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, the most recent coup in 2014 established a de facto military dictatorship.

Tai peoples migrated from southwestern China to mainland Southeast Asia from the 11th century; the oldest known mention of their presence in the region by the exonym Siamese dates to the 12th century. Various Indianised kingdoms such as the Mon, the Khmer Empire and Malay states ruled the region, competing with Thai states such as Ngoenyang, the Sukhothai Kingdom, Lan Na and the Ayutthaya Kingdom, which rivaled each other. European contact began in 1511 with a Portuguese diplomatic mission to Ayutthaya, one of the great powers in the region. Ayutthaya reached its peak during cosmopolitan Narai's reign (1656–88), gradually declining thereafter until being ultimately destroyed in 1767 in a war with Burma. Taksin quickly reunified the fragmented territory and established the short-lived Thonburi Kingdom. He was succeeded in 1782 by Buddha Yodfa Chulaloke, the first monarch of the Chakri dynasty and founder of the Rattanakosin Kingdom, which lasted into the early 20th century.

Through the 18th and 19th centuries, Siam faced pressure from France and the United Kingdom, including forced concessions of territory, but nevertheless it remained the only Southeast Asian country to avoid direct Western rule. Following a bloodless revolution in 1932, Siam became a constitutional monarchy and changed its official name to "Thailand". While it joined the Allies in World War I, Thailand was an Axis satellite in World War II. In the late 1950s, a military coup revived the monarchy's historically influential role in politics. Thailand became a major ally of the United States and played a key anti-communist role in the region. Apart from a brief period of parliamentary democracy in the mid 1970s, Thailand has periodically alternated between democracy and military rule. In the 21st century, Thailand endured a political crisis that culminated in two coups and the establishment of its current and 20th constitution by the military junta.

Thailand is a Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy under a military junta. Thailand is a founding member of ASEAN and remains a major ally of the US.[15][16] Despite its comparatively sporadic changes in leadership, it is considered a regional power in Southeast Asia and a middle power in global affairs.[17] With a high level of human development, the second largest economy in Southeast Asia, and the 20th largest by PPP, Thailand is classified as a newly industrialized economy; manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism are leading sectors of the economy.[18][19]

Etymology

Thailand (/ˈtaɪlænd/ TY-land or /ˈtaɪlənd/ TY-lənd;[20] Thai: ประเทศไทย, RTGS: Prathet Thai, pronounced [pratʰêːt tʰaj] ⓘ), officially the Kingdom of Thailand (Thai: ราชอาณาจักรไทย, RTGS: Ratcha-anachak Thai [râːtt͡ɕʰaʔaːnaːt͡ɕàk tʰaj] ⓘ, Chinese: 泰国), formerly known as Siam (Thai: สยาม, RTGS: Sayam [sajǎːm]), is a country at the centre of the Indochinese peninsula in Southeast Asia.

Etymology of "Siam"

The country has always been called Mueang Thai by its citizens. By outsiders prior to 1949, it was usually known by the exonym Siam (Thai: สยาม RTGS: Sayam, pronounced [sajǎːm], also spelled Siem, Syâm, or Syâma).[citation needed] The word Siam may have originated from Pali suvaṇṇabhūmi (“land of gold”) or Sanskrit श्याम (śyāma, “dark”) or Mon ရာမည(rhmañña, “stranger”). The names Shan and A-hom seem to be variants of the same word. The word Śyâma is possibly not its origin, but a learned and artificial distortion.[clarification needed][21] Another theory is the name derives from Chinese: "Ayutthaya emerged as a dominant centre in the late fourteenth century. The Chinese called this region Xian, which the Portuguese converted into Siam." (Baker and Phongpaichit, A History of Thailand, 8) A further possibility is that Mon-speaking peoples migrating south called themselves 'syem' as do the autochthonous Mon-Khmer-speaking inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula.[citation needed]

The signature of King Mongkut (r. 1851–1868) reads SPPM (Somdet Phra Poramenthra Maha) Mongkut King of the Siamese, giving the name "Siam" official status until 24 June 1939 when it was changed to Thailand.[22] Thailand was renamed to Siam from 1946 to 1948, after which it again reverted to Thailand.

Etymology of "Thailand"

According to George Cœdès, the word Thai (ไทย) means "free man" in the Thai language, "differentiating the Thai from the natives encompassed in Thai society as serfs".[23] A famous Thai scholar argued that Thai (ไท) simply means "people" or "human being", since his investigation shows that in some rural areas the word "Thai" was used instead of the usual Thai word "khon" (คน) for people.[24] According to Michel Ferlus, the ethnonyms Thai/Tai (or Thay/Tay) would have evolved from the etymon *k(ə)ri: 'human being' through the following chain: *kəri: > *kəli: > *kədi:/*kədaj > *di:/*daj > *dajA (Proto-Southwestern Tai) > tʰajA2 (in Siamese and Lao) or > tajA2 (in the other Southwestern and Central Tai languages classified by Li Fangkuei).[25] Michel Ferlus' work is based on some simple rules of phonetic change observable in the Sinosphere and studied for the most part by William H. Baxter (1992).[26]

While Thai people will often refer to their country using the polite form prathet Thai (Thai: ประเทศไทย), they most commonly use the more colloquial term mueang Thai (Thai: เมืองไทย) or simply Thai; the word mueang, archaically referring to a city-state, is commonly used to refer to a city or town as the centre of a region. Ratcha Anachak Thai (Thai: ราชอาณาจักรไทย) means "kingdom of Thailand" or "kingdom of Thai". Etymologically, its components are: ratcha (Sanskrit राजन्, rājan, "king, royal, realm") ; -ana- (Pali āṇā "authority, command, power", itself from the Sanskrit आज्ञा, ājñā, of the same meaning) -chak (from Sanskrit चक्र cakra- "wheel", a symbol of power and rule). The Thai National Anthem (Thai: เพลงชาติ), written by Luang Saranupraphan during the extremely patriotic 1930s, refers to the Thai nation as prathet Thai (Thai: ประเทศไทย). The first line of the national anthem is: prathet thai ruam lueat nuea chat chuea thai (Thai: ประเทศไทยรวมเลือดเนื้อชาติเชื้อไทย), "Thailand is the unity of Thai flesh and blood."

History

Prehistory

There is evidence of continued human habitation in present-day Thailand dated to 20,000 years before present.[28]: 4 Earliest evidence of rice growing was dated 2,000 BCE.[27]: 4 Bronze appeared during 1,250–1,000 BCE.[27]: 4 The site of Ban Chiang in Northeast Thailand currently ranks as the earliest known center of copper and bronze production in Southeast Asia.[29] Iron appeared around 500 BCE.[27]: 5 Kingdom of Funan was the first and most powerful South East Asian kingdom at the time (2nd century BCE).[28]: 5 Mon people established principalities of Dvaravati and kingdom of Hariphunchai in the 6th century. Khmer people established Khmer empire centered in Angkor in the 9th century.[28]: 7 Tambralinga, a Malay state controlling trade through Malacca Strait, rose in the 10th century.[28]: 5 Indochina peninsula was heavily influenced by the culture and religions of India, starting with the Kingdom of Funan to the Khmer Empire.[30]

Thai people are in Tai ethnic group, which were characterized by common linguistic roots.[31]: 2 Chinese chronicles first mentioned Tai peoples in 6th century BC. While there are many assumptions regarding the origin of Tai peoples, David K. Wyatt, a prominent historian on Thailand, argued that their ancestors which at the present inhabit Laos, Thailand, Myanmar, India and China came from Điện Biên Phủ area around 5th and 8th century.[31]: 6 Thai people began migrating into present-day Thailand around 11th century, which Mon and Khmer people occupied at the time.[32] Thus Thai culture was influenced by Indian, Mon and Khmer cultures.[33]

According to French historian George Cœdès, "The Thai first enter history of Farther India in the eleventh century with the mention of Syam slaves or prisoners of war in" Champa epigraphy, and "in the twelfth century, the bas-reliefs of Angkor Wat" where "a group of warriors" are described as Syam.[34]

Early states

After the decline of the Khmer Empire and Kingdom of Pagan in the early 13th century, various states thrived in their place. The domains of Tai people existed from the northeast of present-day India to the north of present-day Laos and to the Malay peninsula. During the 13th century, Tai people have already settled in the core land of Dvaravati and Lavo Kingdom to Nakhon Si Thammarat in the south. There are, however, no records detailing the arrival of the Tais. Around 1240s, Pho Khun Bang Klang Hao, a local Tai ruler, rallied the people to rebel against the Khmer. He later crowned himself the first king of Sukhothai Kingdom in 1238. Mainstream Thai historians count Sukhothai as the first kingdom of Thai people.

Following the decline and fall of the Khmer empire in the 13th–15th century, the Buddhist Tai kingdoms of Sukhothai, Lanna, and Lan Xang (now Laos) were on the rise. However, a century later, the power of Sukhothai was overshadowed by the new Kingdom of Ayutthaya, established in the mid-14th century in the lower Chao Phraya River or Menam area.

Ayutthaya Kingdom

According to the most widely accepted version of its origin, Ayutthaya Kingdom rose from the earlier, nearby Lavo Kingdom and Suvarnabhumi with Uthong as its first king. Its initial expansion is through conquest and political marriage. Before the end of the 15th century, Ayutthaya invaded Khmer Empire twice and sacked its capital Angkor. Ayutthaya then became a regional great power in place of Khmer Empire. Borommatrailokkanat brought about bureaucratic reforms which lasted into the 20th century and created a system of social hierarchy called Sakdina. Ayutthaya was interested in Malay peninsula but failed to conquer Malacca Sultanate which was supported by Chinese Ming Dynasty.

European contact and trade started in the early 16th century, with the envoy of Portuguese duke Afonso de Albuquerque in 1511, followed by the French, Dutch, and English. Ayutthaya then was at war with Burmese Taungoo Dynasty. Multiple wars starting in the 1540s were ultimately ended with capture of the capital in 1570. Then was a period of brief vassalage to Burma until Naresuan proclaimed independence in 1584.

Ayutthaya was an important trade center which was known to trade with China, India, Persia, and Arab lands. The kingdom especially prospered during cosmopolitan Narai's reign (1656–88). Some European travelers regarded Ayutthaya as Asian great powers alongside China and India.[27]: ix However, growing French influence later in his reign was met with nationalist sentiment and led eventually to the revolution of 1688. Trade with the West declined afterwards.

After that, there was a period of relative peace but the kingdom's influence gradually waned, partly because of bloody struggles over each succession, until the capital Ayutthaya was utterly destroyed in 1767 by Burma's new Alaungpaya dynasty.

Anarchy followed destruction of the former capital, with its territories split into five different factions, each controlled by a warlord. Taksin rose to power and proclaimed Thonburi as temporary capital in the same year. He also quickly subdued the other warlords. His forces engaged in wars with Burma, Laos, and Cambodia, which successfully drove the Burmese out of Lan Na in 1775, captured Vientiane in 1778 and tried to install a pro-Thai king in Cambodia in the 1770s. In his final years there was a coup which was caused by his supposedly "insanity," and eventually Taksin and his sons were executed by longtime companion General Chao Phraya Chakri (future Rama I). He was the first king of the ruling Chakri Dynasty and founder of Bangkok (Rattanakosin Kingdom) on April 6, 1782.

Modernization and centralization

Under Rama I, Rattanakosin successfully defended against Burmese attacks and put an end to Burmese invasion. He also created overlordship over large portions of Laos and Cambodia. In 1821, John Crawfurd was sent on a mission to negotiate a new trade agreement with Siam — the first sign of an issue which was to dominate 19th-century Siamese politics.[35]

European pressure mounted and in 1855, during Mongkut's reign, a British mission led by Sir John Bowring, Governor of Hong Kong, led to the conclusion of Bowring Treaty, first of many unequal treaties with Western countries. However, Thailand is the only Southeast Asian nation to never have been colonized by any Western power,[36] in part because Britain and France agreed in 1896 to make the Chao Phraya valley their buffer state.[37]

Western influence nevertheless led to many reforms in the 19th century. Chulalongkorn introduced the Monthon system, where centralized officials were sent to oversee the entire land, thus effectively ending the power of all local dynasties. He also abolished corvée system and slavery in Siam, his best-known act. There were also major concessions to France and Britain, most notably the loss of a large protectorate territory east of the Mekong composed of present-day Laos and Cambodia and the ceding of four Malay provinces to Britain in Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909.

In 1917, Siam joined the Allies of World War I and is counted as one of the victors of World War I.

Constitutional monarchy, World War II, and Cold War

The bloodless revolution took place in 1932 carried out by the Khana Ratsadon group of military and civilian officials resulted in a transition of power, when King Prajadhipok was forced to grant the people of Siam their first constitution, thereby ending centuries of absolute monarchy. His conflicting view with the government led to abdication. The government selected Ananda Mahidol to be the new king.

Later that decade, the military wing of Khana Ratsadon came to dominate Siamese politics. Field Marshall Plaek Phibunsongkhram built fascism, and decreed cultural mandates which changed the name of the kingdom to "Thailand" and affected many aspects of daily life. After France was conquered by Nazi Germany in June 1940, Thailand took the opportunity to retake territories conceded to the French many decades earlier, which Thailand won the majority of the battles. The conflict came to an end with Japanese mediation.

On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched an invasion of Thailand, and fighting broke out shortly before Phibun ordered an armistice. Japan was granted free passage, and on December 21, Thailand and Japan signed a military alliance with a secret protocol, wherein Tokyo agreed to help Thailand regain territories lost to the British and French.[38] Subsequently, Thailand declared war on the United States and the United Kingdom on January 25, 1942, and while the government undertook to "assist" Japan, some people launched an active anti-Japanese Free Thai Movement. After the war, most Allied powers did not recognize Thailand's declaration of war.

In June 1946, young King Ananda was found dead under mysterious circumstances. His younger brother Bhumibol Adulyadej succeeded the throne.

In 1954, Thailand signed Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) to became an active ally of the United States. Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat launched a coup in 1957, which removed Khana Ratsadon from politics. He also revived the monarchy's role in politics. Military dictatorships at the time were supported by US government, and Thailand joined anti-communist measures in the region alongside the US, most notably participation in the Vietnam War between 1965 and 1971.

The period brought about increasing modernisation and Westernisation. Internal conflict regarding economic difficulties which began in 1968 led to 1973 Thai popular uprising, an important event in Thai modern history.

Contemporary history

Constant unrest and instability, as well as fear of communist takeover after Fall of Saigon, made some ultra-right groups brand increasingly leftist students as communists. This culminated in Thammasat University massacre in October 1976. A coup d'état on that very day brought Thailand a new ultra-right government, which oppressed many media outlets, officials, and intellectuals, and fueled the Communist insurgency further. Another coup in the following year installed a more moderate government, which offered amnesty to communist fighters in 1978. The Party abandoned the insurgency by 1983. Thailand had its first elected Prime Minister in 1988.[39]

Suchinda Kraprayoon, who was the coup leader in 1991 and said he would not seek to become Prime Minister, was nominated as one by majority coalition government after the 1992 general election. This caused a popular demonstration in Bangkok, which ended with a military crackdown. Bhumibol intervened in the event and Suchinda then resigned.

The 1997 Asian financial crisis originated in Thailand and forced the country to take an IMF loan with unpopular provisions. The populist Thai Rak Thai party, led by prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, governed from 2001 until 2006.[40] A South Thailand insurgency escalated starting from 2004. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami hit the country, mostly in the south. Massive protests against Thaksin, led by the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD), ended with a coup d'état in 2006.

In 2007, a civilian government led by the Thaksin-allied People's Power Party (PPP) was elected. Another protest led by PAD ended with the dissolution of PPP, and the Democrat Party led a coalition government in its place. The pro-Thaksin United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD) protested both in 2009 and in 2010.

After the general election of 2011, the populist Pheu Thai Party won a majority and Yingluck Shinawatra, Thaksin's younger sister, became Prime Minister. The People's Democratic Reform Committee organized another anti-Shinawatra protest, which ended with another coup d'état in 2014. The National Council for Peace and Order, a military junta led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha, has led the country since. The referendum and adoption of Thailand's current constitution happened under the junta's rule. In 2016 Bhumibol, the longest reigning Thai king, died, and his son Vajiralongkorn ascended the throne.

Politics and government

Prior to 1932, all legislative powers were vested in the monarch. This had been the case since the foundation of the Sukhothai Kingdom in the 12th century as the king was seen as a "Dharmaraja" or "king who rules in accordance with Dharma", (the Buddhist law of righteousness). Modern absolute monarchy was established by Chulalongkorn when he transformed the decentralized protectorate system into a unitary state. On 24 June 1932, Khana Ratsadon (People's Party) carried out a bloodless revolution which ended the absolute rule.

The politics of Thailand is conducted within the framework of a constitutional monarchy, whereby the Prime Minister is the head of government and a hereditary monarch is head of state. The judiciary is supposed to be independent of the executive and the legislative branches, although judicial rulings are suspected of being based on political considerations rather than on existing law.[41] However, since May 2014, Thailand has been ruled by a military junta, the National Council for Peace and Order.

Thailand has had 20 constitutions and charters since 1932, including the latest and current 2017 Constitution. Throughout this time, the form of government has ranged from military dictatorship to electoral democracy, but all governments have acknowledged a hereditary monarch as the head of state.[42][43] Thailand had the 4th most coup in the world.[44] "Uniformed or ex-military men have led Thailand for 55 of the 83 years" between 1932 and 2009.[45]

The legislative according to 2007 Constitution was the bicameral National Assembly composed of the Senate, the 150-member upper house, and House of Representatives, the 350-member lower house. Since 2014 coup, it was replaced by a rubber stamp, unicameral National Legislative Assembly.

The current King of Thailand is Vajiralongkorn (or Rama X) since October 2016. Under the constitution the king is given very little power, but remains a figurehead and symbol of the Thai nation. As the head of state, however, he is given some powers and has a role to play in the workings of government. According to the constitution, the king is head of the armed forces. He is required to be Buddhist as well as the defender of all faiths in the country. The king also retained some traditional powers such as the power to appoint his heirs, the power to grant pardons, and the royal assent. The king is aided in his duties by the Privy Council of Thailand.

Since the 2000s, two political parties dominated Thai general elections: one was Pheu Thai Party (which was a successor of People's Power Party and Thai Rak Thai Party respectively) and the other was Democrat Party. The political parties which support Thaksin Shinawatra won the most representatives every general election since 2001.

Human rights

The 2007 constitution was partially abrogated by the military dictatorship that came to power in May 2014.[46]

Thailand's kings are protected by lèse-majesté laws which allows critics to be jailed for three to fifteen years.[47] After the 2014 Thai coup d'état, Thailand had the highest number of lèse-majesté prisoners in the nation's history.[48][49] In 2017, the military court in Thailand sentenced a man to 35 years in prison for violating the country's lèse-majesté law.[49]Thailand has been rated not free on the Freedom House Index since 2014.[50]

Geography

Totalling 513,120 square kilometres (198,120 sq mi),[1] Thailand is the 50th-largest country by total area. It is slightly smaller than Yemen and slightly larger than Spain.

Thailand comprises several distinct geographic regions, partly corresponding to the provincial groups. The north of the country is the mountainous area of the Thai highlands, with the highest point being Doi Inthanon in the Thanon Thong Chai Range at 2,565 metres (8,415 ft) above sea level. The northeast, Isan, consists of the Khorat Plateau, bordered to the east by the Mekong River. The centre of the country is dominated by the predominantly flat Chao Phraya river valley, which runs into the Gulf of Thailand.

Southern Thailand consists of the narrow Kra Isthmus that widens into the Malay Peninsula. Politically, there are six geographical regions which differ from the others in population, basic resources, natural features, and level of social and economic development. The diversity of the regions is the most pronounced attribute of Thailand's physical setting.

The Chao Phraya and the Mekong River are the indispensable water courses of rural Thailand. Industrial scale production of crops use both rivers and their tributaries. The Gulf of Thailand covers 320,000 square kilometres (124,000 sq mi) and is fed by the Chao Phraya, Mae Klong, Bang Pakong, and Tapi Rivers. It contributes to the tourism sector owing to its clear shallow waters along the coasts in the southern region and the Kra Isthmus. The eastern shore of the Gulf of Thailand is an industrial centre of Thailand with the kingdom's premier deepwater port in Sattahip and its busiest commercial port, Laem Chabang.

The Andaman Sea is a precious natural resource as it hosts the most popular and luxurious resorts in Asia. Phuket, Krabi, Ranong, Phang Nga and Trang, and their islands, all lay along the coasts of the Andaman Sea and, despite the 2004 tsunami, they remain a tourist magnet for visitors from around the world.

Plans have resurfaced for a canal which would connect the Andaman Sea to the Gulf of Thailand, analogous to the Suez and the Panama Canals. The idea has been greeted positively by Thai politicians as it would cut fees charged by the Ports of Singapore, improve ties with China and India, lower shipping times, and eliminate pirate attacks in the Strait of Malacca, and support the Thai government's policy of being the logistical hub for Southeast Asia. The canal, it is claimed, would improve economic conditions in the south of Thailand, which relies heavily on tourism income, and it would also change the structure of the Thai economy by making it an Asia logistical hub. The canal would be a major engineering project and has an expected cost of US$20–30 billion.

Climate

Thailand's climate is influenced by monsoon winds that have a seasonal character (the southwest and northeast monsoon).[51]: 2 The southwest monsoon, which starts from May until October is characterized by movement of warm, moist air from the Indian Ocean to Thailand, causing abundant rain over most of the country.[51]: 2 The northeast monsoon, starting from October until February brings cold and dry air from China over most of Thailand.[51]: 2 In southern Thailand, the northeast monsoon brings mild weather and abundant rainfall on the eastern coast of that region.[51]: 2 Most of Thailand has a "tropical wet and dry or savanna climate" type (Köppen's Tropical savanna climate).[52] The south and the eastern tip of the east have a tropical monsoon climate.

Thailand is divided into three seasons.[51]: 2 The first is the rainy or southwest monsoon season (mid–May to mid–October) which prevails over most of the country.[51]: 2 This season is characterized by abundant rain with August and September being the wettest period of the year.[51]: 2 This can occasionally lead to floods.[51]: 4 In addition to rainfall caused by the southwest monsoon, the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) and tropical cyclones also contribute to producing heavy rainfall during the rainy season.[51]: 2 Nonetheless, dry spells commonly occur for 1 to 2 weeks from June to early July.[51]: 4 This is due to the northward movement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone to southern China.[51]: 4 Winter or the northeast monsoon starts from mid–October until mid–February.[51]: 2 Most of Thailand experiences dry weather during this season with mild temperatures.[51]: 2 : 4 The exception is the southern parts of Thailand where it receives abundant rainfall, particularly during October to November.[51]: 2 Summer or the pre–monsoon season runs from mid–February until mid–May and is characterized by warmer weather.[51]: 3

Due to its inland nature and latitude, the north, northeast, central and eastern parts of Thailand experience a long period of warm weather.[51]: 3 During the hottest time of the year (March to May), temperatures usually reach up to 40 °C (104 °F) or more with the exception of coastal areas where sea breezes moderate afternoon temperatures.[51]: 3 In contrast, outbreaks of cold air from China can bring colder temperatures; in some cases (particularly the north and northeast) close to or below 0 °C (32 °F).[51]: 3 Southern Thailand is characterized by mild weather year-round with less diurnal and seasonal variations in temperatures due to maritime influences.[51]: 3

Most of the country receives a mean annual rainfall of 1,200 to 1,600 mm (47 to 63 in).[51]: 4 However, certain areas on the windward sides of mountains such as Ranong province in the west coast of southern Thailand and eastern parts of Trat Province receive more than 4,500 mm (180 in) of rainfall per year.[51]: 4 The driest areas are on the leeward side in the central valleys and northernmost portion of south Thailand where mean annual rainfall is less than 1,200 mm (47 in).[51]: 4 Most of Thailand (north, northeast, central and east) is characterized by dry weather during the northeast monsoon and abundant rainfall during the southwest monsoon.[51]: 4 In the southern parts of Thailand, abundant rainfall occurs in both the northeast and southwest monsoon seasons with a peak in September for the western coast and a peak in November–January on the eastern coast.[51]: 4

Environment

Thailand has a mediocre but improving performance in the global Environmental Performance Index (EPI) with an overall ranking of 91 out of 180 countries in 2016. This is also a mediocre rank in the Asia Pacific region specifically, but ahead of countries like Indonesia and China. The EPI was established in 2001 by the World Economic Forum as a global gauge to measure how well individual countries perform in implementing the United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals. The environmental areas where Thailand performs worst (i.e. highest ranking) are air quality (167), environmental effects of the agricultural industry (106) and the climate and energy sector (93), the later mainly because of a high CO2 emission per KWh produced. Thailand performs best (i.e. lowest ranking) in water resource management (66), with some major improvements expected for the future too, and sanitation (68).[53][54]

Wildlife

The elephant is Thailand's national symbol. Although there were 100,000 domesticated elephants in Thailand in 1850, the population of elephants has dropped to an estimated 2,000.[55] Poachers have long hunted elephants for ivory and hides, and now increasingly for meat.[56] Young elephants are often captured for use in tourist attractions or as work animals, although their use has declined since the government banned logging in 1989. There are now more elephants in captivity than in the wild, and environmental activists claim that elephants in captivity are often mistreated.[57]

Poaching of protected species remains a major problem. Hunters have decimated the populations of tigers, leopards, and other large cats for their valuable pelts. Many animals (including tigers, bears, crocodiles, and king cobras) are farmed or hunted for their meat, which is considered a delicacy, and for their supposed medicinal properties. Although such trade is illegal, the famous Bangkok market Chatuchak is still known for the sale of endangered species.[58]

The practice of keeping wild animals as pets threatens several species. Baby animals are typically captured and sold, which often requires killing the mother. Once in captivity and out of their natural habitat, many pets die or fail to reproduce. Affected populations include the Asiatic black bear, Malayan sun bear, white-handed lar, pileated gibbon and binturong.[59]

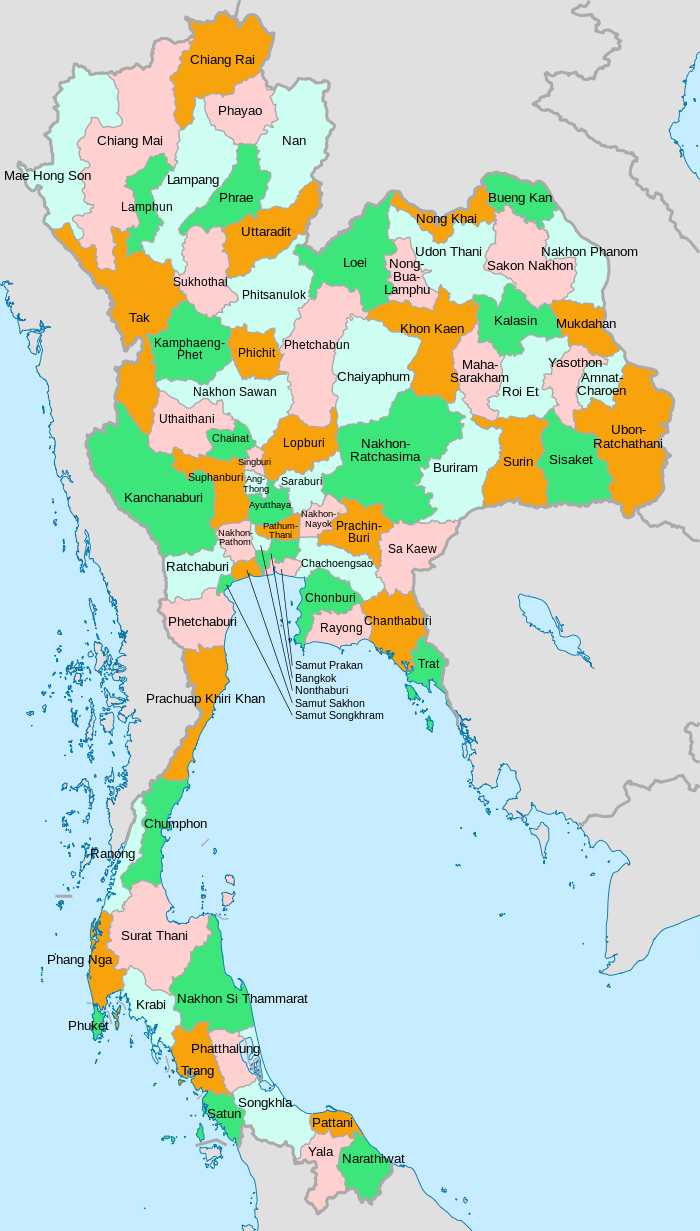

Administrative divisions

Thailand is divided into 76 provinces (จังหวัด, changwat), which are gathered into five groups of provinces by location. There are also two specially-governed districts: the capital Bangkok (Krung Thep Maha Nakhon) and Pattaya. Bangkok is at provincial level and thus often counted as a province.

Each province is divided into districts and the districts are further divided into sub-districts (tambons). As of 2017[update][60] there were 878 districts (อำเภอ, amphoe) and the 50 districts of Bangkok (เขต, khet), which is further divided into 7,255 subdistricts (ตำบล, tambon) in the 76 provinces or Bangkok's subdistricts (แขวง, khwaeng). Some parts of the provinces bordering Bangkok are also referred to as Greater Bangkok (ปริมณฑล, pari monthon). These provinces include Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani, Samut Prakan, Nakhon Pathom and Samut Sakhon. The name of each province's capital city (เมือง, mueang) is the same as that of the province. For example, the capital of Chiang Mai Province (Changwat Chiang Mai) is Mueang Chiang Mai or Chiang Mai.

Regions

Thai provinces are administrated by regions. The regions that Thailand uses to divide the provinces is the four-region division system. It divides the country into the four regions: Northern Thailand, Northeastern Thailand, Central Thailand and Southern Thailand. Each region has its own different historical background, culture, language and people.

In contrast to the administrative divisions of the Provinces of Thailand, Thailand is a Unitary state, the provincial Governors, district chiefs, and district clerks are appointed by the central government. The regions themselves do not have an administrative character, but are used for geographical, statistical, geological, meteorological or touristic purposes.

Southern region

Thailand controlled the Malay Peninsula as far south as Malacca in the 15th century and held much of the peninsula, including Temasek (Singapore), some of the Andaman Islands, and a colony on Java, but eventually contracted when the British used force to guarantee their suzerainty over the sultanate.

Mostly the northern states of the Malay Sultanate presented annual gifts to the Thai king in the form of a golden flower—a gesture of tribute and an acknowledgement of vassalage. The British intervened in the Malay State and with the Anglo-Siamese Treaty tried to build a railway from the south to Bangkok. Thailand relinquished sovereignty over what are now the northern Malay provinces of Kedah, Perlis, Kelantan, and Terengganu to the British. Satun and Pattani Provinces were given to Thailand.

The Malay peninsular provinces were occupied by the Japanese during World War II, and infiltrated by the Malayan Communist Party (CPM) from 1942 to 2008, when they sued for peace with the Malaysian and Thai governments after the CPM lost its support from Vietnam and China subsequent to the Cultural Revolution. Recent insurgent uprisings may be a continuation of separatist fighting which started after World War II with Sukarno's support for the PULO. Most victims since the uprisings have been Buddhist and Muslim bystanders.

Foreign relations

The foreign relations of Thailand are handled by the Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Thailand participates fully in international and regional organisations. It is a major non-NATO ally and Priority Watch List Special 301 Report of the United States. The country remains an active member of ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Thailand has developed increasingly close ties with other ASEAN members: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Brunei, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar, and Vietnam, whose foreign and economic ministers hold annual meetings. Regional co-operation is progressing in economic, trade, banking, political, and cultural matters. In 2003, Thailand served as APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation) host. Dr. Supachai Panitchpakdi, the former Deputy Prime Minister of Thailand, currently serves as Secretary-General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). In 2005 Thailand attended the inaugural East Asia Summit.

In recent years, Thailand has taken an increasingly active role on the international stage. When East Timor gained independence from Indonesia, Thailand, for the first time in its history, contributed troops to the international peacekeeping effort. Its troops remain there today as part of a UN peacekeeping force. As part of its effort to increase international ties, Thailand has reached out to such regional organisations as the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Thailand has contributed troops to reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Thaksin initiated negotiations for several free trade agreements with China, Australia, Bahrain, India, and the US. The latter especially was criticised, with claims that uncompetitive Thai industries could be wiped out.[61]

Thaksin also announced that Thailand would forsake foreign aid, and work with donor countries to assist in the development of neighbours in the Greater Mekong Sub-region.[62] Thaksin sought to position Thailand as a regional leader, initiating various development projects in poorer neighbouring countries like Laos. More controversially, he established close, friendly ties with the Burmese dictatorship.[63]

Thailand joined the US-led invasion of Iraq, sending a 423-strong humanitarian contingent.[64] It withdrew its troops on 10 September 2004. Two Thai soldiers died in Iraq in an insurgent attack.

Abhisit appointed Peoples Alliance for Democracy leader Kasit Piromya as foreign minister. In April 2009, fighting broke out between Thai and Cambodian troops on territory immediately adjacent to the 900-year-old ruins of Cambodia's Preah Vihear Hindu temple near the border. The Cambodian government claimed its army had killed at least four Thais and captured 10 more, although the Thai government denied that any Thai soldiers were killed or injured. Two Cambodian and three Thai soldiers were killed. Both armies blamed the other for firing first and denied entering the other's territory.[65][66]

Armed forces

The Royal Thai Armed Forces (กองทัพไทย; RTGS: Kong Thap Thai) constitute the military of the Kingdom of Thailand. It consists of the Royal Thai Army (กองทัพบกไทย), the Royal Thai Navy (กองทัพเรือไทย), and the Royal Thai Air Force (กองทัพอากาศไทย). It also incorporates various paramilitary forces.

The Thai Armed Forces have a combined manpower of 306,000 active duty personnel and another 245,000 active reserve personnel.[67] The head of the Thai Armed Forces (จอมทัพไทย, Chom Thap Thai) is the king,[68] although this position is only nominal. The armed forces are managed by the Ministry of Defence of Thailand, which is headed by the Minister of Defence (a member of the cabinet of Thailand) and commanded by the Royal Thai Armed Forces Headquarters, which in turn is headed by the Chief of Defence Forces of Thailand.[69] In 2011, Thailand's known military expenditure totalled approximately US$5.1 billion.[70] Thailand ranked 16th worldwide in the Military Strength Index based on the Credit Suisse report in September 2015.

According to the constitution, serving in the armed forces is a duty of all Thai citizens.[71] However, only males over the age of 21, who have not gone through reserve training of the Territorial Defence Student, are given the option of volunteering for the armed forces, or participating in the random draft. The candidates are subjected to varying lengths of training, from six months to two years of full-time service, depending on their education, whether they have partially completed the reserve training course, and whether they volunteered prior to the draft date (usually 1 April every year).

Candidates with a recognised bachelor's degree serve one year of full-time service if they are conscripted, or six months if they volunteer with the military officer at their district office (สัสดี, satsadi). Likewise, the training length is also reduced for those who have partially completed the three-year reserve training course of the Territorial Defence Students (ร.ด., ro do). A person who completed one year out of three will only have to serve full-time for one year. Those who completed two years of reserve training will only have to do six months of full-time training, while those who complete three years or more of reserve training will be exempted entirely.

Royal Thai Armed Forces Day is celebrated on 18 January, commemorating the victory of Naresuan of the Ayutthaya Kingdom in battle against the crown prince of the Taungoo Dynasty in 1593.[citation needed]

Education

In 2014 the literacy rate was 93.5%.[72] Education is provided by a well-organized school system of kindergartens, primary, lower secondary and upper secondary schools, numerous vocational colleges, and universities. The private sector of education is well developed and significantly contributes to the overall provision of education which the government would not be able to meet with public establishments. Education is compulsory up to and including age 14, with the government providing free education through to age 17.[citation needed]

Teaching relies heavily on rote learning rather than on student-centred methodology. The establishment of reliable and coherent curricula for its primary and secondary schools is subject to such rapid changes that schools and their teachers are not always sure what they are supposed to be teaching, and authors and publishers of textbooks are unable to write and print new editions quickly enough to keep up with the volatility. Issues concerning university entrance has been in constant upheaval for a number of years. Nevertheless, Thai education has seen its greatest progress in the years since 2001. Most of the present generation of students are computer literate. Thailand was ranked 54th out of 56 countries globally for English proficiency, the second-lowest in Asia.[73]

Students in ethnic minority areas score consistently lower in standardised national and international tests.[74] [75] [76] This is likely due to unequal allocation of educational resources, weak teacher training, poverty, and low Thai language skill, the language of the tests.[74] [77] [78]

Extensive nationwide IQ tests were administered to 72,780 Thai students from December 2010 to January 2011. The average IQ was found to be 98.59, which is higher than previous studies have found. IQ levels were found to be inconsistent throughout the country, with the lowest average of 88.07 found in the southern region of Narathiwat Province and the highest average of 108.91 reported in Nonthaburi Province. The Ministry of Public Health blames the discrepancies on iodine deficiency and steps are being taken to require that iodine be added to table salt, a practice common in many Western countries.[79]

In 2013, the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology announced that 27,231 schools would receive classroom-level access to high-speed internet.[dead link][80]

Science and technology

The National Science and Technology Development Agency is an agency of the government of Thailand which supports research in science and technology and its application in the Thai economy.[citation needed]

The Synchrotron Light Research Institute (SLRI) is a Thai synchrotron light source for physics, chemistry, material science, and life sciences. It is at the Suranaree University of Technology (SUT), in Nakhon Ratchasima, about 300 kilometres (190 miles) northeast of Bangkok. The institute, financed by the Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST), houses the only large scale synchrotron in Southeast Asia. It was originally built as the SORTEC synchrotron in Japan and later moved to Thailand and modified for 1.2 GeV operation. It provides users with regularly scheduled light.[citation needed]

Internet

In Bangkok, there are 23,000 free public Wi-Fi Internet hotspots.[81] The Internet in Thailand includes 10Gbit/s high speed fibre-optic lines that can be leased and ISPs such as KIRZ that provide residential Internet services.[citation needed]

The Internet is censored by the Thai government, making some sites unreachable.[82] The organisations responsible are the Royal Thai Police, the Communications Authority of Thailand, and the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (MICT).[citation needed]

Economy

| Economic indicators | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP | ฿14.53 trillion (2016) | [83] |

| GDP growth | 3.9% (2017) | [84] |

| Inflation • Headline • Core |

0.7% (2017) 0.6% (2017) |

[84] |

| Employment-to-population ratio | 68.0% (2017) | [85]: 29 |

| Unemployment | 1.2% (2017) | [84] |

| Total public debt | ฿6.37 trillion (Dec. 2017) | [86] |

| Poverty | 8.61% (2016) | [85]: 36 |

| Net household worth | ฿20.34 trillion (2010) | [87]: 2 |

Thailand is an emerging economy and is considered a newly industrialised country. Thailand had a 2013 GDP of US$673 billion (on a purchasing power parity [PPP] basis).[88] Thailand is the 2nd largest economy in Southeast Asia after Indonesia. Thailand ranks midway in the wealth spread in Southeast Asia as it is the 4th richest nation according to GDP per capita, after Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia.

Thailand functions as an anchor economy for the neighbouring developing economies of Laos, Myanmar, and Cambodia. In the third quarter of 2014, the unemployment rate in Thailand stood at 0.84% according to Thailand's National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB).[89]

Recent economic history

Thailand experienced the world's highest economic growth rate from 1985 to 1996 – averaging 12.4% annually. In 1997 increased pressure on the baht, a year in which the economy contracted by 1.9%, led to a crisis that uncovered financial sector weaknesses and forced the Chavalit Yongchaiyudh administration to float the currency. Prime Minister Chavalit Yongchaiyudh was forced to resign after his cabinet came under fire for its slow response to the economic crisis. The baht was pegged at 25 to the US dollar from 1978 to 1997. The baht reached its lowest point of 56 to the US dollar in January 1998 and the economy contracted by 10.8% that year, triggering the Asian financial crisis.

Thailand's economy started to recover in 1999, expanding 4.2–4.4% in 2000, thanks largely to strong exports. Growth (2.2%) was dampened by the softening of the global economy in 2001, but picked up in the subsequent years owing to strong growth in Asia, a relatively weak baht encouraging exports, and increased domestic spending as a result of several mega projects and incentives of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, known as Thaksinomics. Growth in 2002, 2003, and 2004 was 5–7% annually.

Growth in 2005, 2006, and 2007 hovered around 4–5%. Due both to the weakening of the US dollar and an increasingly strong Thai currency, by March 2008 the dollar was hovering around the 33 baht mark. While Thaksinomics has received criticism, official economic data reveals that between 2001 and 2011, Isan's GDP per capita more than doubled to US$1,475, while, over the same period, GDP in the Bangkok area increased from US$7,900 to nearly US$13,000.[90]

With the instability surrounding major 2010 protests, the GDP growth of Thailand settled at around 4–5%, from highs of 5–7% under the previous civilian administration. Political uncertainty was identified as the primary cause of a decline in investor and consumer confidence. The IMF predicted that the Thai economy would rebound strongly from the low 0.1% GDP growth in 2011, to 5.5% in 2012 and then 7.5% in 2013, due to the monetary policy of the Bank of Thailand, as well as a package of fiscal stimulus measures introduced by the former Yingluck Shinawatra government.[91]

Following the Thai military coup of 22 May 2014, the AFP global news agency published an article that claimed that the nation was on the verge of recession. The article focused on the departure of nearly 180,000 Cambodians from Thailand due to fears of an immigration clampdown, but concluded with information on the Thai economy's contraction of 2.1% quarter-on-quarter, from January to the end of March 2014.[92]

Income, poverty and wealth

Thais have median wealth per one adult person of $1,469 in 2016,[93]: 98 increasing from $605 in 2010.[93]: 34 In 2016, Thailand was ranked 87th in Human Development Index, and 70th in the inequality-adjusted HDI.[94]

In 2017, median household income was ฿26,946 per month.[95]: 1 Top quintile household had 45.0% share of all income, while bottom quintile household had 7.1%.[95]: 4 There were 26.9 million persons who had the bottom 40% of income earning less than ฿5,344 per person per month.[96]: 5 During 2013–2014 Thai political crisis, a survey found that anti-government PDRC mostly (32%) had a monthly income of more than ฿50,000, while pro-government UDD mostly (27%) had between ฿10,000 and ฿20,000.[97]: 7

In 2014, Credit Suisse reported that Thailand was the world's third most unequal country, behind Russia and India.[98] Top 10% richest held 79% of the country's asset.[98] Top 1% richest held 58% worth of the economy.[98] Thai 50 richest families had a total net worth accounting to 30% of GDP.[98]

In 2016, Thailand's 5.81 million people lived in poverty, or 11.6 million people (17.2% of population) if "near poor" is included.[96]: 1 Proportion of the poor relative to total population in each region was 12.96% in the Northeast, 12.35% in the South, and 9.83% in the North.[96]: 2 In 2017, there were 14 million people who applied for social welfare (yearly income of less than ฿100,000 was required).[98] At the end of 2017, Thailand's total household debt was ฿11.76 trillion.[85]: 5 In 2010, 3% of all household were bankrupt.[87]: 5 In 2016, there were estimated 30,000 homeless persons in the country.[99]

Exports and manufacturing

The economy of Thailand is heavily export-dependent, with exports accounting for more than two-thirds of gross domestic product (GDP). Thailand exports over US$105 billion worth of goods and services annually.[1] Major exports include cars, computers, electrical appliances, rice, textiles and footwear, fishery products, rubber, and jewellery.[1]

Substantial industries include electric appliances, components, computer components, and vehicles. Thailand's recovery from the 1997–1998 Asian financial crisis depended mainly on exports, among various other factors. As of 2012[update], the Thai automotive industry was the largest in Southeast Asia and the 9th largest in the world.[100][101][102] The Thailand industry has an annual output of near 1.5 million vehicles, mostly commercial vehicles.[102]

Most of the vehicles built in Thailand are developed and licensed by foreign producers, mainly Japanese and South Korean. The Thai car industry takes advantage of the ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) to find a market for many of its products. Eight manufacturers, five Japanese, two US, and Tata of India, produce pick-up trucks in Thailand.[103] Thailand is the second largest consumer of pick-up trucks in the world, after the US.[citation needed] In 2014, pick-ups accounted for 42% of all new vehicle sales in Thailand.[103]

Tourism

Tourism makes up about 6% of the economy. Thailand was the most visited country in Southeast Asia in 2013, according to the World Tourism Organisation. Estimates of tourism receipts directly contributing to the Thai GDP of 12 trillion baht range from 9 percent (1 trillion baht) (2013) to 16 percent.[104] When including the indirect effects of tourism, it is said to account for 20.2 percent (2.4 trillion baht) of Thailand's GDP.[105]: 1

The Tourism Authority of Thailand (TAT) uses the slogan "Amazing Thailand" to promote Thailand internationally. In 2015, this was supplemented by a "Discover Thainess" campaign.[106]

Asian tourists primarily visit Thailand for Bangkok and the historical, natural, and cultural sights in its vicinity. Western tourists not only visit Bangkok and surroundings, but in addition many travel to the southern beaches and islands. The north is the chief destination for trekking and adventure travel with its diverse ethnic minority groups and forested mountains. The region hosting the fewest tourists is Isan in the northeast. To accommodate foreign visitors, the Thai government established a separate tourism police with offices in the major tourist areas and its own central emergency telephone number.[107]

Thailand's attractions include diving, sandy beaches, hundreds of tropical islands, nightlife, archaeological sites, museums, hill tribes, flora and bird life, palaces, Buddhist temples and several World Heritage sites. Many tourists follow courses during their stay in Thailand. Popular are classes in Thai cooking, Buddhism and traditional Thai massage. Thai national festivals range from Thai New Year Songkran to Loy Krathong. Many localities in Thailand also have their own festivals. Among the best-known are the "Elephant Round-up" in Surin, the "Rocket Festival" in Yasothon, Suwannaphum District, Phanom Phrai District both district are located in Roi Et Province and the "Phi Ta Khon" festival in Dan Sai. Thai cuisine has become famous worldwide with its enthusiastic use of fresh herbs and spices.

Bangkok shopping malls offer a variety of international and local brands. Towards the north of the city, and easily reached by skytrain or underground, is the Chatuchak Weekend Market. It is possibly the largest market in the world, selling everything from household items to live, and sometimes endangered, animals.[108] The "Pratunam Market" specialises in fabrics and clothing. The night markets in the Silom area and on Khaosan Road are mainly tourist-oriented, selling items such as T-shirts, handicrafts, counterfeit watches and sunglasses. In the vicinity of Bangkok one can find several floating markets such as the one in Damnoen Saduak. The "Sunday Evening Walking Street Market", held on Rachadamnoen Road inside the old city, is a shopping highlight of a visit to Chiang Mai up in northern Thailand. It attracts many locals as well as foreigners. The "Night Bazaar" is Chiang Mai's more tourist-oriented market, sprawling over several city blocks just east of the old city walls towards the river.

Prostitution in Thailand and sex tourism also form a de facto part of the economy. Campaigns promote Thailand as exotic to attract tourists.[109] Cultural milieu combined with poverty and the lure of money have caused prostitution and sex tourism in particular to flourish in Thailand. One estimate published in 2003 placed the trade at US$4.3 billion per year or about 3% of the Thai economy.[110] According to research by Chulalongkorn University on the Thai illegal economy, prostitution in Thailand in the period between 1993 and 1995, made up around 2.7% of the GDP.[111] It is believed that at least 10% of tourist dollars are spent on the sex trade.[112]

Thailand is at the forefront of the growing practice of sex-reassignment surgery (SRS). Statistic taken from 2014, illustrated the country's medical tourism industry attracting over 2.5 million visitors per year.[113] In 1985–1990, only 5% of foreign transsexual patients visited Thailand for sex-reassignment surgery. In more recent years, 2010–2012, more than 90% of the visitors traveled to Thailand for SRS.[114]

Agriculture

Forty-nine per cent of Thailand's labour force is employed in agriculture.[115] This is down from 70% in 1980.[115] Rice is the most important crop in the country and Thailand had long been the world's leading exporter of rice, until recently falling behind both India and Vietnam.[116] Thailand has the highest percentage of arable land, 27.25%, of any nation in the Greater Mekong Subregion.[117] About 55% of the arable land area is used for rice production.[118]

Agriculture has been experiencing a transition from labour-intensive and transitional methods to a more industrialised and competitive sector.[115] Between 1962 and 1983, the agricultural sector grew by 4.1% per year on average and continued to grow at 2.2% between 1983 and 2007.[115] The relative contribution of agriculture to GDP has declined while exports of goods and services have increased.

Energy

75% of Thailand's electrical generation is powered by natural gas in 2014.[119] Coal-fired power plants produce an additional 20% of electricity, with the remainder coming from biomass, hydro, and biogas.[119]

Thailand produces roughly one-third of the oil it consumes. It is the second largest importer of oil in SE Asia. Thailand is a large producer of natural gas, with reserves of at least 10 trillion cubic feet. After Indonesia, it is the largest coal producer in SE Asia, but must import additional coal to meet domestic demand.

Transportation

Informal Economy

Thailand has an diverse and robust informal labor sector-- in 2012, it was estimated that informal workers comprised 62.6% of the Thai workforce. The Ministry of Labor defines informal workers to be individuals who work in informal economies and do not have employee status under a given country's Labor Protection Act (LPA). The informal sector in Thailand has grown significantly over the past 60 years over the course of Thailand's gradual transition from an agriculture-based economy to becoming more industrialized and service-oriented.[120] Between 1993–1995, ten percent of the Thai labor force moved from the agricultural sector to urban and industrial jobs, especially in the manufacturing sector. It is estimated that between 1988–1995, the number of factory workers in the country doubled from two to four million, as Thailand's GDP tripled.[121] While the Asian Financial Crisis that followed in 1997 hit the Thai economy hard, the industrial sector continued to expand under widespread deregulation, as Thailand was mandated to adopt a range of structural adjustment reforms upon receiving funding from the IMF and World Bank. These reforms implemented an agenda of increased privatization and trade liberalization in the country, and decreased federal subsidization of public goods and utilities, agricultural price supports, and regulations on fair wages and labor conditions.[122] These changes put further pressure on the agricultural sector, and prompted continued migration from the rural countryside to the growing cities. Many migrant farmers found work in Thailand's growing manufacturing industry, and took jobs in sweatshops and factories with few labor regulations and often exploitative conditions.[123]

Those that could not find formal factory work, including illegal migrants and the families of rural Thai migrants that followed their relatives to the urban centers, turned to the informal sector to provide the extra support needed for survival-- under the widespread regulation imposed by the structural adjustment programs, one family member working in a factory or sweatshop made very little. Scholars argue that the economic consequences and social costs of Thailand's labor reforms in the wake of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis fell on individuals and families rather than the state. This can be described as the "externalization of market risk", meaning that as the country's labor market became increasingly deregulated, the burden and responsibility of providing an adequate livelihood shifted from employers and the state to the workers themselves, whose families had to find jobs in the informal sector to make up for the losses and subsidize the wages being made by their relatives in the formal sector. The weight of these economic changes hit migrants and the urban poor especially hard, and the informal sector expanded rapidly as a result.[122]

Today, informal labor in Thailand is typically broken down into three main groups: subcontracted/self employed/home-based workers, service workers (including those that are employed in restaurants, as street vendors, masseuses, taxi drivers, and as domestic workers), and agricultural workers. Not included in these categories are those that work in entertainment, nightlife, and the sex industry. Individuals employed in these facets of the informal labor sector face additional vulnerabilities, including recruitment into circles of sexual exploitation and human trafficking.[120]

In general, education levels are low in the informal sector. A 2012 study found that 64% of informal workers had not completed education beyond primary school. Many informal workers are also migrants, only some of which have legal status in the country. Education and citizenship are two main barriers to entry for those looking to work in formal industries, and enjoy the labor protections and social security benefits that come along with formal employment. Because the informal labor sector is not recognized under the Labor Protection Act (LPA), informal workers are much more vulnerable labor to exploitation and unsafe working conditions than those employed in more formal and federally recognized industries. While some Thai labor laws provide minimal protections to domestic and agricultural workers, they are often weak and difficult to enforce. Furthermore, Thai social security policies fail to protect against the risks many informal workers face, including workplace accidents and compensation as well as unemployment and retirement insurance. Many informal workers are not legally contracted for their employment, and many do not make a living wage.[120] As a result, labor trafficking is common in the region, affecting children and adults, men and women, and migrants and Thai citizens alike.

Demographics

| Population in Thailand[8][9] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Million | ||

| 1950 | 20.7 | ||

| 2000 | 62.9 | ||

| 2021 | 71.6 | ||

Thailand had a population of 71,601,103[8][9] as of 2021[update]. Thailand's population is largely rural, concentrated in the rice-growing areas of the central, northeastern, and northern regions. Thailand had an urban population of 45.7% as of 2010[update], concentrated mostly in and around the Bangkok Metropolitan Area.

Thailand's government-sponsored family planning program resulted in a dramatic decline in population growth from 3.1% in 1960 to around 0.4% today. In 1970, an average of 5.7 people lived in a Thai household. At the time of the 2010 census, the average Thai household size was 3.2 people.

Ethnic groups

Thai nationals make up the majority of Thailand's population, 95.9% in 2010. The remaining 4.1% of the population are Burmese (2.0%), others 1.3%, and unspecified 0.9%.[1]

According to the Royal Thai Government's 2011 Country Report to the UN Committee responsible for the International Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, available from the Department of Rights and Liberties Promotion of the Thai Ministry of Justice,[3]: 3 62 ethnic communities are officially recognised in Thailand. Twenty million Central Thai (together with approximately 650,000 Khorat Thai) make up approximately 20,650,000 (34.1 percent) of the nation's population of 60,544,937[124] at the time of completion of the Mahidol University Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand data (1997).[125]

The 2011 Thailand Country Report provides population numbers for mountain peoples ('hill tribes') and ethnic communities in the Northeast and is explicit about its main reliance on the Mahidol University Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand data.[125] Thus, though over 3.288 million people in the Northeast alone could not be categorised, the population and percentages of other ethnic communities circa 1997 are known for all of Thailand and constitute minimum populations. In descending order, the largest (equal to or greater than 400,000) are a) 15,080,000 Lao (24.9 percent) consisting of the Thai Lao[2] (14 million) and other smaller Lao groups, namely the Thai Loei (400–500,000), Lao Lom (350,000), Lao Wiang/Klang (200,000), Lao Khrang (90,000), Lao Ngaew (30,000), and Lao Ti (10,000; b) six million Khon Muang (9.9 percent, also called Northern Thais); c) 4.5 million Pak Tai (7.5 percent, also called Southern Thais); d) 1.4 million Khmer Leu (2.3 percent, also called Northern Khmer); e) 900,000 Malay (1.5%); f) 500,000 Ngaw (0.8 percent); g) 470,000 Phu Thai (0.8 percent); h) 400,000 Kuy/Kuay (also known as Suay) (0.7 percent), and i) 350,000 Karen (0.6 percent).[3]: 7–13 Thai Chinese, those of significant Chinese heritage, are 14% of the population,[6] while Thais with partial Chinese ancestry comprise up to 40% of the population.[126] Thai Malays represent 3% of the population, with the remainder consisting of Mons, Khmers and various "hill tribes". The country's official language is Thai and the primary religion is Theravada Buddhism, which is practised by around 95% of the population.

Increasing numbers of migrants from neighbouring Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, as well as from Nepal and India, have pushed the total number of non-national residents to around 3.5 million as of 2009[update], up from an estimated 2 million in 2008, and about 1.3 million in 2000.[127] Some 41,000 Britons live in Thailand.[128]

Population centres

Template:Largest cities of Thailand

Language

The official language of Thailand is Thai, a Tai–Kadai language closely related to Lao, Shan in Myanmar, and numerous smaller languages spoken in an arc from Hainan and Yunnan south to the Chinese border. It is the principal language of education and government and spoken throughout the country. The standard is based on the dialect of the central Thai people, and it is written in the Thai alphabet, an abugida script that evolved from the Khmer alphabet.

Sixty-two languages were recognised by the Royal Thai Government in the 2011 Country Report to the UN Committee responsible for the International Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, which employed an ethnolinguistic approach and is available from the Department of Rights and Liberties Promotion of the Thai Ministry of Justice.[3]: 3 Southern Thai is spoken in the southern provinces, and Northern Thai is spoken in the provinces that were formerly part of the independent kingdom of Lan Na. For the purposes of the national census, which does not recognise all 62 languages recognised by the Royal Thai Government in the 2011 Country Report, four dialects of Thai exist; these partly coincide with regional designations.

The largest of Thailand's minority languages is the Lao dialect of Isan spoken in the northeastern provinces. Although sometimes considered a Thai dialect, it is a Lao dialect, and the region where it is traditionally spoken was historically part of the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang.[citation needed] In the far south, Kelantan-Pattani Malay is the primary language of Malay Muslims. Varieties of Chinese are also spoken by the large Thai Chinese population, with the Teochew dialect best-represented.

Numerous tribal languages are also spoken, including many Austroasiatic languages such as Mon, Khmer, Viet, Mlabri and Orang Asli; Austronesian languages such as Cham and Moken; Sino-Tibetan languages like Lawa, Akha, and Karen; and other Tai languages such as Tai Yo, Phu Thai, and Saek. Hmong is a member of the Hmong–Mien languages, which is now regarded as a language family of its own.

English is a mandatory school subject, but the number of fluent speakers remains low, especially outside cities.

Religion

Thailand's prevalent religion is Theravada Buddhism, which is an integral part of Thai identity and culture. Active participation in Buddhism is among the highest in the world. According to the 2000 census, 94.6% and 93.58% in 2010 of the country's population self-identified as Buddhists of the Theravada tradition. Muslims constitute the second largest religious group in Thailand, comprising 4.9% of the population.[1][129]

Islam is concentrated mostly in the country's southernmost provinces: Pattani, Yala, Satun, Narathiwat, and part of Songkhla Chumphon, which are predominantly Malay, most of whom are Sunni Muslims. Christians represent 0.9% (2000) and 1.17% (2015) of the population, with the remaining population consisting of Hindus and Sikhs, who live mostly in the country's cities. There is also a small but historically significant Jewish community in Thailand dating back to the 17th century.

According to the 2015 census,[7] 67,328,562 Thailand residents belonged to the following religious groups:

| Religion | Number (2010),[130] |

Percentage | Number (2016) |

Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | 61,746,429 | 93.58% | 63,620,298 | 94.50% |

| Islam | 3,259,340 | 4.94% | 2,892,311 | 4.29% |

| Christianity | 789,376 | 1.20% | 787,589 | 1.17% |

| Hinduism | 41,808 | 0.06% | 22,110 | 0.03% |

| No religion | 46.122 | 0.07% | 2,925 | 0.005% |

| Other religions | 70.742 | 0.11% | 1,583 | 0.002% |

| Sikhism | 11,124 | 0.02% | 1,030 | 0.001% |

| Confucianism | 16,718 | 0.02% | 716 | 0.001% |

According to the 2015 census,[7] 67,328,562 Thailand residents by Region belonged to the following religious groups:

| Religion | Bangkok | % | Central Region | % | Northern Region | % | Northeastern Region | % | Southern Region | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | 8,197,188 | 93.95% | 18,771,520 | 97.57% | 11,044,018 | 96.23% | 18,698,599 | 99.83% | 6,908,973 | 75.45% |

| Islam | 364,855 | 4.18% | 247,430 | 1.29% | 35,561 | 0.31% | 16,851 | 0.09% | 2,227,613 | 24.33% |

| Christianity | 146,592 | 1.68% | 214,444 | 1.11% | 393,969 | 3.43% | 13,825 | 0.07% | 18,759 | 0.21% |

| Hinduism | 16,306 | 0.19% | 5,280 | 0.03% | 207 | 0.002% | 318 | 0.001% | - | |

| Sikhism | - | 0.00% | - | 0.00% | 378 | 0.003% | - | 0.00% | 491 | 0.005% |

| No religion | 289 | 0.00% | 473 | 0.002% | 1,001 | 0.01% | 436 | 0.002% | 726 | 0.008% |

| Other religions | - | 0.00% | 294 | 0.00% | 1,808 | 0.16% | - | 0.00% | 359 | 0.004% |

Health

Health and medical care is overseen by the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), along with several other non-ministerial government agencies, with total national expenditures on health amounting to 4.3 percent of GDP in 2009. Non-communicable diseases form the major burden of morbidity and mortality, while infectious diseases including malaria and tuberculosis, as well as traffic accidents, are also important public health issues.

The current Minister for Public Health is Prof. Emeritus Piyasakol Sakolsatayadorn, M.D. and the Permanent Secretary of Ministry of Public Health is Jedsada Chokdamrongsuk, M.D. Somsak Chunharas, MD, MPH, was once Deputy Minister for Public Health and is currently a Senior Leadership Fellow at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston.[131][132]

Culture

Thai culture has been shaped by many influences, including Indian, Lao, Burmese, Cambodian, and Chinese.

Its traditions incorporate a great deal of influence from India, China, Cambodia, and the rest of Southeast Asia. Thailand's national religion, Theravada Buddhism, is central to modern Thai identity. Thai Buddhism has evolved over time to include many regional beliefs originating from Hinduism, animism, as well as ancestor worship. The official calendar in Thailand is based on the Eastern version of the Buddhist Era (BE), which is 543 years ahead of the Gregorian (Western) calendar. Thus the year 2015 is 2558 BE in Thailand.

Several different ethnic groups, many of which are marginalised, populate Thailand. Some of these groups spill over into Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia and have mediated change between their traditional local culture, national Thai, and global cultural influences. Overseas Chinese also form a significant part of Thai society, particularly in and around Bangkok. Their successful integration into Thai society has allowed for this group to hold positions of economic and political power. Thai Chinese businesses prosper as part of the larger bamboo network, a network of overseas Chinese businesses operating in the markets of Southeast Asia that share common family and cultural ties.[133]

The traditional Thai greeting, the wai, is generally offered first by the younger of the two people meeting, with their hands pressed together, fingertips pointing upwards as the head is bowed to touch face to fingertips, usually coinciding with the spoken words "sawatdi khrap" for male speakers, and "sawatdi kha" for females. The elder may then respond in the same way. Social status and position, such as in government, will also have an influence on who performs the wai first. For example, although one may be considerably older than a provincial governor, when meeting it is usually the visitor who pays respect first. When children leave to go to school, they are taught to wai their parents to indicate their respect. The wai is a sign of respect and reverence for another, similar to the namaste greeting of India and Nepal.

As with other Asian cultures, respect towards ancestors is an essential part of Thai spiritual practice. Thais have a strong sense of hospitality and generosity, but also a strong sense of social hierarchy. Seniority is paramount in Thai culture. Elders have by tradition ruled in family decisions or ceremonies. Older siblings have duties to younger ones.

Taboos in Thailand include touching someone's head or pointing with the feet, as the head is considered the most sacred and the foot the lowest part of the body.

Cuisine

Thai cuisine blends five fundamental tastes: sweet, spicy, sour, bitter, and salty. Common ingredients used in Thai cuisine include garlic, chillies, lime juice, lemon grass, coriander, galangal, palm sugar, and fish sauce (nam pla). The staple food in Thailand is rice, particularly jasmine variety rice (also known as "hom Mali" rice) which forms a part of almost every meal. Thailand was long[when?] the world's largest exporter of rice, and Thais domestically consume over 100 kg of milled rice per person per year.[118] Over 5,000 varieties of rice from Thailand are preserved in the rice gene bank of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), based in the Philippines. The king of Thailand is the official patron of IRRI.[135]

Media

Thai society has been influenced in recent years by its widely available multi-language press and media. There are some English and numerous Thai and Chinese newspapers in circulation. Most Thai popular magazines use English headlines as a chic glamour factor. Many large businesses in Bangkok operate in English as well as other languages.

Thailand is the largest newspaper market in Southeast Asia with an estimated circulation of over 13 million copies daily in 2003. Even upcountry, out of Bangkok, the media flourish. For example, according to Thailand's Public Relations Department Media Directory 2003–2004, the nineteen provinces of Isan, Thailand's northeastern region, hosted 116 newspapers along with radio, TV, and cable. Since then, another province, Bueng Kan, was incorporated, totalling twenty provinces. In addition, a military coup on 22 May 2014 led to severe state restrictions on all media and forms of expression.

Units of measurement

Thailand generally uses the metric system, but traditional units of measurement for land area are used, and imperial units of measurement are occasionally used for building materials, such as wood and plumbing fixtures. Years are numbered as B.E. (Buddhist Era) in educational settings, civil service, government, contracts, and newspaper datelines. However, in banking, and increasingly in industry and commerce, standard Western year (Christian or Common Era) counting is the standard practice.[136]

Sports

Muay Thai (Thai: มวยไทย, RTGS: Muai Thai, [muaj tʰaj], lit. "Thai boxing") is a native form of kickboxing and Thailand's signature sport. It incorporates kicks, punches, knees and elbow strikes in a ring with gloves similar to those used in Western boxing and this has led to Thailand gaining medals at the Olympic Games in boxing.

Association football has overtaken muay Thai as the most widely followed sport in contemporary Thai society. Thailand national football team has played the AFC Asian Cup six times and reached the semifinals in 1972. The country has hosted the Asian Cup twice, in 1972 and in 2007. The 2007 edition was co-hosted together with Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam. It is not uncommon to see Thais cheering their favourite English Premier League teams on television and walking around in replica kit. Another widely enjoyed pastime, and once a competitive sport, is kite flying.

Volleyball is rapidly growing as one of the most popular sports. The women's team has often participated in the World Championship, World Cup, and World Grand Prix Asian Championship. They have won the Asian Championship twice and Asian Cup once. By the success of the women's team, the men team has been growing as well.

Takraw (Thai: ตะกร้อ) is a sport native to Thailand, in which the players hit a rattan ball and are only allowed to use their feet, knees, chest, and head to touch the ball. Sepak takraw is a form of this sport which is similar to volleyball. The players must volley a ball over a net and force it to hit the ground on the opponent's side. It is also a popular sport in other countries in Southeast Asia. A rather similar game but played only with the feet is buka ball.

Snooker has enjoyed increasing popularity in Thailand in recent years, with interest in the game being stimulated by the success of Thai snooker player James Wattana in the 1990s.[137] Other notable players produced by the country include Ratchayothin Yotharuck, Noppon Saengkham and Dechawat Poomjaeng.[138]