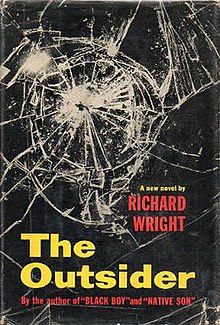

The Outsider (Wright novel)

First edition | |

| Author | Richard Wright |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | African American literature |

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

Publication date | 1953 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

The Outsider is a novel by American author Richard Wright, first published in 1953. The Outsider is Richard Wright's second installment in a story of epic proportions, a complex master narrative to show American racism in raw and ugly terms. It was the kind of racism that Wright knew and experienced, a racism from which most black people of his own time could not escape, and it remained the central element in his fiction. The Outsider appeared during the height of McCarthyism in the United States and the advent of the Cold War in Europe, two events that had a significant bearing on its initial reception.

Plot summary[edit]

The novel's central character, symbolically named Cross Damon, represents the 20th century man in frenzied pursuit of freedom. Cross is an intellectual Negro, the product of a culture that rejects him. He is further alienated by his "habit of incessant reflection," his feeling that the experiences and actions of his life have so far taken place without his free assent, and a profound conviction that there must be more to life, some meaning and justification that have hitherto eluded him.

When Cross is introduced (in "Book One: Dread") he is drinking too much, partly in an effort to forget his problems (of which he has many) but mostly to deaden the pain caused by his urgent and frustrated sense of life. There is an accident in which he is reported dead and so he sets out to create his own identity, and thus, he hopes, to discover truth.

This search for the absolute compels him to commit four murders and ends in his despair and violent death. En route, he encounters totalitarianism in its most-likely-to-succeed form, Communism. Though he agrees with these other "outsiders" that power is the central reality of society and that "man is nothing in particular," he is outraged by their acceptance and cynical exploitation of these "facts". "That’s not enough," he screams before he kills a Communist who has just told him that there is no more to life.

You say life is just life, a simple act of accidental possession in the hands of him who happens to have it. But what's suffering? That rests in the senses... You might argue that you could snatch a life, blot out a consciousness and get away with it because you're strong and free enough to do it; but why turn a consciousness into a flame of suffering and let it lie, squirming...?

Having rejected religion, the past and present organization of society, the proposed totalitarian alternative and the kindred uncontrollable violence of his own behavior as a "free" man, Cross abandons ideas and pins his last hope on love. But his mistress commits suicide when she sees him as he is.

There follows a chapter in which the Law, personified by a hunchbacked district attorney who understands Cross Damon, convicts him of a crime and condemns him, but is powerless to give his life significance by punishment. After this Cross is murdered. The district attorney comes to his death bed and asks how was life and Cross dies murmuring, "It was horrible."

Literary significance and criticism[edit]

The Outsider was Wright's first book to receive predominantly negative reviews.[citation needed] Reviewers[who?] were primarily critical of its characterization, particularly the absence of sufficient motivation for Damon's violence.[citation needed] Many[who?] thought that Wright should have "stayed gold".[citation needed] The novel's mix of melodramatic action and lengthy rhetorical exposition seemed disruptive. Black reviewers believed that Wright's interest in existentialism indicated a separation from his roots. Most[who?] reviewers found the unrelieved pessimism of the novel unattractive.[citation needed]

The novel has often been considered the result of Wright's involvement with existential thinkers following his break from Marxism in the 1940s. The novel seems to mark the low point of Wright's despair, for it lacks Camus's humanitarian hope or Jean-Paul Sartre’s belief in social change.[citation needed] Later critics, however, have suggested that The Outsider is a rejection of existentialism or is even a Christian existentialist novel.

Existential or not, The Outsider is a logical extension of Wright’s earlier fiction and thought. In Native Son (1940), central character Bigger expresses in a less articulate manner the same sort of rage and dread felt by Damon. In Wright's short story "The Man Who Lived Underground", central character Fred Daniels, like Damon, wants to share his hard-earned knowledge with others. In Art and Fiction, Wright maintained that personal freedom was conditioned on the freedom of others. Thus, in The Outsider Wright addressed familiar themes but consciously tried to move beyond the racial limitations of his earlier work.

Wright, influenced primarily by German nihilism and his earlier involvement in the Communist party, condemns Marxism for its repression of individuality inherent in the structure of such group ideologies. Damon, molded by his repressive childhood as an African American child with a Christian mother, spends much of the novel escaping or preventing coercion against him by others. In essence, Wright describes the African American struggle as one inherently in opposition to society's constructs and violence and anger as a direct result of an upbringing rooted in racial oppression. The majority[who?] of early criticism aimed at The Outsider falsely regarded it as a form of existential propaganda and failed to effectively analyze the connection between Wright's life and experiences before the train accident and his subsequent violence.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

- African American literature

- Black Boy - 1945 autobiography by Richard Wright

- Native Son - 1940 novel by Richard Wright

- Black Marxism - 1983 book by Cedric Robinson

- Existentialism

- Nihilism

References[edit]