The Atlantic

| border Cover of The Atlantic | |

| Editor-in-chief | Jeffrey Goldberg |

|---|---|

| Categories | Literature, political science, foreign affairs |

| Frequency | 10 issues a year |

| Publisher | Hayley Romer |

| Total circulation (2015) | 494,539[1] |

| Founder | |

| Founded | 1857 |

| First issue | November 1, 1857 (as The Atlantic Monthly) |

| Company | Emerson Collective |

| Country | United States |

| Based in | Washington, D.C.[2] |

| Language | American English |

| Website | www |

| ISSN | 1072-7825 |

The Atlantic is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher, founded in 1857 as The Atlantic Monthly in Boston, Massachusetts.

The publication is majority owned by Emerson Collective, an organization led by the billionaire philanthropist and investor Laurene Powell Jobs, which purchased its stake in 2017 from businessman and publisher David G. Bradley, who retains a minority interest and remains the operating partner.[3]

Created as a literary and cultural commentary magazine, it has a reputation in the 21st century for a politically moderate viewpoint in its reporting.[4] The magazine has notably recognized and published new writers and poets, as well as encouraged major careers. In the 19th century, it published leading writers' commentary on abolition, education, and other major issues in contemporary political affairs, and continued to publish leading intellectual thought. The periodical was named Magazine of the Year by the American Society of Magazine Editors (ASME) in 2016.[5]

The first issue of the magazine was published by Phillips, Sampson and Company on November 1, 1857.[6][7] Phillips, Sampson and Company was a very well known publishing firm, led by Moses Dresser Phillips, and The Atlantic Monthly's successful launch in the midst of the Panic of 1857 was due in no small part to the firm's established name, Phillips, Sampson and Company's recruitment of popular contributors, and Moses Dresser Phillips's marketing and distribution efforts.[8]The magazine's initiator, and one of the founders, was Francis H. Underwood, an assistant to Moses Dresser Phillips.[9][10][11] Underwood received less recognition than his partners because he was "neither a 'humbug' nor a Harvard man".[12] The other founding sponsors were prominent writers, including: Ralph Waldo Emerson; Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.; Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; Harriet Beecher Stowe; John Greenleaf Whittier; and James Russell Lowell, who served as its first editor.[13]

After struggling with financial hardship and a series of ownership changes since the late 20th century, the magazine was reformatted in the early 21st century as a general editorial magazine. Focusing on "foreign affairs, politics, and the economy [as well as] cultural trends," it is now primarily aimed at a target audience of serious national readers and "thought leaders."[14][15] In 2010, The Atlantic posted its first profit in a decade. In profiling the publication at the time, The New York Times noted the accomplishment was the result of "a cultural transfusion, a dose of counterintuition and a lot of digital advertising revenue."[16]

TheAtlantic.com, The Atlantic's flagship website, provides daily coverage and analysis of breaking news, politics and international affairs, education, technology, health, science, and culture. In addition to the print magazine and website, The Atlantic houses an editorial events arm, AtlanticLIVE; Atlantic Re:think, its creative marketing team; and Atlantic Media Strategies, a creative agency and consulting firm. The Atlantic's President is Bob Cohn.

Format, publication frequency, and name

The magazine, subscribed to by over 450,000 readers, now publishes ten times a year.[17] As the former name suggests, it was a monthly magazine for 144 years until 2001, when it published eleven issues; it published ten issues yearly from 2003 on, dropped "Monthly" from the cover starting with the January/February 2004 issue, and officially changed the name in 2007. The Atlantic features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.[18]

On January 22, 2008, TheAtlantic.com dropped its subscriber wall and allowed users to freely browse its site, including all past archives.[19] By 2011 The Atlantic's web properties included TheAtlanticWire.com, a news- and opinion-tracking site launched in 2009,[20] and TheAtlanticCities.com, a stand-alone website started in 2011 that was devoted to global cities and trends.[21] According to a Mashable profile in December 2011, "traffic to the three web properties recently surpassed 11 million uniques per month, up a staggering 2500% since The Atlantic brought down its paywall in early 2008."[22]

In December 2011, a new Health Channel launched on TheAtlantic.com, incorporating coverage of food, as well as topics related to the mind, body, sex, family, and public health.[23] TheAtlantic.com has also expanded to visual storytelling with the addition of the In Focus photo blog, curated by Alan Taylor.[24] and in 2011 it created its Video Channel.[25] Initially created as an aggregator, The Atlantic's Video component, 'Atlantic' Studios, has since evolved in an in-house production studio that create custom video series and original documentaries.[26]

In 2015, TheAtlantic.com launched a dedicated Science section[27] and in January 2016 it redesigned and expanded its politics section in conjunction with the 2016 U.S. presidential race.[28]

Literary history

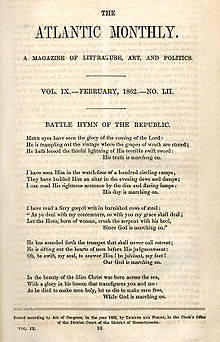

A leading literary magazine, The Atlantic has published many significant works and authors. It was the first to publish pieces by the abolitionists Julia Ward Howe ("Battle Hymn of the Republic" on February 1, 1862), and William Parker, whose slave narrative, "The Freedman's Story" was published in February and March 1866. It also published Charles W. Eliot's "The New Education", a call for practical reform, that led to his appointment to presidency of Harvard University in 1869; works by Charles Chesnutt before he collected them in The Conjure Woman (1899); and poetry and short stories, helping launch many national literary careers.[citation needed] For example, Emily Dickinson, after reading an article in The Atlantic by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, asked him to become her mentor.[citation needed] In 2005, the magazine won a National Magazine Award for fiction.[citation needed]

The magazine also published many of the works of Mark Twain, including one that was lost until 2001.[citation needed] Editors have recognized major cultural changes and movements. For example, the magazine published Martin Luther King, Jr.'s defense of civil disobedience in "Letter from Birmingham Jail" in August 1963.[30]

The magazine has also published speculative articles that inspired the development of new technologies. The classic example is Vannevar Bush's essay "As We May Think" (July 1945), which inspired Douglas Engelbart and later Ted Nelson to develop the modern workstation and hypertext technology.[citation needed]

In addition to publishing notable fiction and poetry, The Atlantic has emerged in the 21st century as an influential platform for longform storytelling and newsmaker interviews. Influential cover stories have included Anne Marie Slaughter's "Why Women Still Can't Have It All" (2012) and Ta-Nehisi Coates's "Case for Reparations" (2014).[32] In 2015, Jeffrey Goldberg's "Obama Doctrine" was a widely discussed by American media and prompted response by many world leaders.[33]

As of 2017, writers and frequent contributors to the print magazine include James Fallows, Jeffrey Goldberg, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Molly Ball, Caitlin Flanagan, James Hamblin, Julia Ioffe, Jonathan Rauch, McKay Coppins, Rosie Gray, Gillian White, Adrienne LaFrance, Vann Newkirk, Derek Thompson, David Frum, Peter Beinart, and James Parker.

Ownership

Until recent decades, The Atlantic was known as a distinctively New England literary magazine (as opposed to Harper's and later The New Yorker, both published in New York City). It achieved a national reputation and was important to the careers of many American writers and poets.[citation needed] By its third year, it was published by the noted Boston publishing house Ticknor and Fields (later to become part of Houghton Mifflin[citation needed]), based in the city known for literary culture. The magazine was purchased in 1908 by its then editor, Ellery Sedgwick, but remained in Boston.

In 1980, the magazine was acquired by Mortimer Zuckerman, property magnate and founder of Boston Properties, who became its Chairman. On September 27, 1999, Zuckerman transferred ownership of the magazine to David G. Bradley, owner of the National Journal Group, which focused on news of Washington, D.C., and government. Bradley had promised that the magazine would stay in Boston for the foreseeable future, as it did for the next five and a half years.

In April 2005, however, the publishers announced that the editorial offices would be moved from their longtime home at 77 North Washington Street in Boston to join the company's advertising and circulation divisions in Washington, D.C.[34] Later in August, Bradley told the New York Observer that the move was not made to save money — near-term savings would be $200,000–$300,000, a relatively small amount that would be swallowed by severance-related spending — but instead would serve to create a hub in Washington where the top minds from all of Bradley's publications could collaborate under the Atlantic Media Company umbrella. Few of the Boston staff agreed to move, and Bradley embarked on an open search for a new editorial staff.[35]

In 2006, Bradley hired James Bennet as editor-in-chief; he had been the Jerusalem bureau chief for The New York Times. He also hired writers, including Jeffrey Goldberg and Andrew Sullivan.[36] Jay Lauf joined the organization as publisher and vice-president in 2008; as of 2017, he was publisher and president of Quartz.[37]

Bennet and Bob Cohn became co-presidents of The Atlantic in early 2014, and Cohn became the publication's sole president in March 2016.[38] Jeffrey Goldberg was named editor in chief in October 2016.[39]

On July 28, 2017, The Atlantic announced that multi-billionaire investor and philanthropist Laurene Powell Jobs (the widow of former Apple Inc. chairman and CEO Steve Jobs) had acquired majority ownership through her Emerson Collective organization, with a staff member of Emerson Collective, Peter Lattman, being immediately named as The Atlantic‘s vice chairman. David G. Bradley and Atlantic Media retained a minority share position in this sale.[40]

Politics

Throughout its 159-year history, The Atlantic has been reluctant to recommend candidates in elections. In 1860, three years into publication, The Atlantic's then-editor James Russell Lowell endorsed Abraham Lincoln for his first run for president and also endorsed the abolition of slavery.[41] In 1964, 104 years later, Edward Weeks wrote on behalf of the editorial board in endorsing Lyndon B. Johnson and rebuking Barry Goldwater's candidacy.[42] In 2016, the editorial board endorsed a presidential candidate, for the third time since the magazine's founding: Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton, in a rebuke of Donald Trump's candidacy.[43]

The Wire

The Wire (previously known as The Atlantic Wire) was a sister site of TheAtlantic.com that aggregated news and opinions from online, print, radio, and television outlets.[44][45][46] When The Atlantic Wire first launched in 2009, it curated op-eds from across the media spectrum and summarized significant positions in each debate.[46] Expanded to encompass news and original reporting, regular features include "What I Read", showcasing the media diets of individuals from the worlds of entertainment, journalism, and politics, and "Trimming the Times",[47] a summary of the feature editor's choices of the best content in The New York Times. The Atlantic Wire rebranded itself as The Wire in November 2013.[48][49]

The Wire was folded back into The Atlantic in 2014.[50]

CityLab

CityLab (formerly The Atlantic Cities) is the latest expansion of The Atlantic's digital properties, launched in September 2011. The stand-alone site has been described as exploring and explaining "the most innovative ideas and pressing issues facing today's global cities and neighborhoods."[51]

The site was co-founded as The Atlantic Cities by Richard Florida, urban theorist, professor. In 2014, it was rebranded as CityLab.com. Today, CityLab.com's coverage areas include design, politics, crime, and housing. Among its offerings are Navigator, "a guide to urban life," and CityFixer, which curates solutions-based stories around a dozen topics.[52]

In 2015, CityLab partnered with Univision to launch CityLab Latino, which features original journalism in Spanish as well as translated reporting from CityLab.com.[53]

Reputation

In June 2006, the Chicago Tribune named The Atlantic one of the top ten English-language magazines, describing it as "a gracefully aging ... 150-year-old granddaddy of periodicals" because "it keeps us smart and in the know" with cover stories on the then-forthcoming fight over Roe v. Wade. It also lauded regular features such as "Word Fugitives" and "Primary Sources" as "cultural barometers."[54]

On January 14, 2013, The Atlantic's website published "sponsor content" about David Miscavige, the leader of the Church of Scientology. While the magazine had previously published advertising looking like articles, this one was widely criticized. The page comments were moderated by the marketing team, not by editorial staff; comments critical of the church were being removed while comments praising the church were being downvoted by readers. Later that day, The Atlantic removed the piece from its website and issued an apology.[55][56][57]

List of editors

- James Russell Lowell, 1857–61

- James Thomas Fields, 1861–71

- William Dean Howells, 1871–81

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich, 1881–90

- Horace Elisha Scudder, 1890–98

- Walter Hines Page, 1898–99

- Bliss Perry, 1899–1909

- Ellery Sedgwick, 1909–38

- Edward A. Weeks, 1938–66

- Robert Manning, 1966–80

- William Whitworth, 1980–99

- Michael Kelly, 1999–2003

- Cullen Murphy, 2003–06 (interim editor, never named editor in chief)

- James Bennet, 2006–16

- Jeffrey Goldberg, 2016–present[58]

List of issues

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 113. Contributor Carl Sandburg Collections (University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign Library). Atlantic Monthly Company. 1914. Retrieved April 1, 2013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

See also

References

- ^ "eCirc for Consumer Magazines". Alliance for Audited Media. December 31, 2015. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ "Historical Facts About The Atlantic". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 21, 2016.

- ^ White, Gillian B. (July 28, 2017). "Emerson Collective Acquires Majority Stake in The Atlantic". The Atlantic. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "The Atlantic Monthly". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Steigrad, Alexandra (February 2, 2016). "The American Society of Magazine Editors Crowns The Atlantic Magazine of the Year at Ellies". WWD. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Berman, Judy (November 10, 2011). "Famous Magazines' First Covers". Flavorwire. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ French, Alex. "The Very First Issues of 19 Famous Magazines". Mental Floss. Retrieved August 10, 2015.

- ^ McMaster, MaryKate. "A Publisher's Hand: Strategic Gambles and Cultural Leadership by Moses Dresser Phillips in Antebellum America." (Ph.D. dissertation, The College of William and Mary, 2001).

- ^ Chevalier, Tracy (2012). "The Atlantic Monthly American magazine, 1857". Encyclopaedia of the Essay. "The Atlantic Monthly was founded in Boston in 1857 by Francis Underwood (an assistant to the publisher..."

- ^ Sedgwick, Ellery (2009). "A History of the Atlantic Monthly, 1857-1909". p. 3. "The Atlantic was founded in 1857 by Francis Underwood, an assistant to the publisher Moses Phillips, and a group of New..."

- ^ Whittier, John Greenleaf (1975). The Letters of John Greenleaf Whittier. Vol. 2. p. 318. "...however, was the founding of the Atlantic Monthly in 1857. Initiated by Francis Underwood and with Lowell as its first editor, the magazine had been sponsored and organized by Lowell, Emerson, Holmes, and Longfellow. "

- ^ Goodman, Susan (2011). Republic of Words: The Atlantic Monthly and Its Writers. p. 90.

- ^ "The Atlantic | History, Ownership, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "The Atlantic". amazon.com. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ "Home page". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ Peters, Jeremy W. (December 12, 2010). "Web Focus Helps Revitalize The Atlantic". The New York Times. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Kuczynski, Alex (May 7, 2001). "Media Talk: This Summer, It's the Atlantic Not-Monthly". The New York Times. Retrieved October 7, 2010. A change of name was not officially announced when the format first changed from a strict monthly (appearing 12 times a year) to a slightly lower frequency.

- ^ "The Atlantic". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "Editors' Note". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Summers, Nick (January 31, 2011). "Exclusive: Ex-Gawker Guy Snyder to Head Atlantic Wire, New Manhattan Staff". The New York Observer. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Welton, Caysey (September 15, 2011). "The Atlantic Debuts TheAtlanticCities.com". FOLIO Magazine. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Indvik, Lauren (December 19, 2011). "Inside The Atlantic: How One Magazine Got Profitable by Going 'Digital First'". Mashable. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Moses, Lucia (December 13, 2011). "'The Atlantic' Continues Expansion With Health Channel". AdWeek. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Kaufman, Rachel (January 19, 2011). "Alan Taylor Jumps to The Atlantic". Media Bistro's Media Jobs Daily. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Kafka, Peter (August 4, 2011). "The Atlantic Launches a Video Aggregator With a Twist". All Things D. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Dreier, Troy. "The Atlantic Adapts: A Legendary Magazine Meets Online Video - Streaming Media Magazine". Streaming Media Magazine. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Andersen, Ross. "Science Has a New Home on TheAtlantic.com". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Atlantic Launches Politics and Policy Expansion". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Boston Directory, 1868.

- ^ The Editors (April 16, 2013). "Martin Luther King's 'Letter From Birmingham Jail'". The Atlantic. pp. 78–88.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ http://www.rheingold.com/texts/tft/9.html.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) H.Rheingold, Tools for Thought, especially chapter 9 - ^ "'The Atlantic's' Ta-Nehisi Coates Builds 'A Case For Reparations'". NPR.org. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Landler, Mark (March 10, 2016). "Obama Criticizes the 'Free Riders' Among America's Allies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ Feeney, Mark; Mehegan, David (April 15, 2005). "Atlantic, 148-year institution, leaving city: Magazine of Twain, James, Howells heads to capital". The Boston Globe.

- ^ "Atlantic owner scours country for cinder-editor". New York Observer. August 29 – September 5, 2005.

- ^ Kurtz, Howard (August 6, 2007). "The Atlantic's Owner Ponies Up". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ^ "Atlantic masthead". The Atlantic. Retrieved October 7, 2010.

- ^ https://www.theatlantic.com/press-releases/archive/2016/03/bob-cohn-named-sole-president-of-the-atlantic/473610/

- ^ https://www.theatlantic.com/press-releases/archive/2016/10/jeffrey-goldberg-named-editor-in-chief-of-the-atlantic/503576/

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/28/business/media/atlantic-media-emerson-collective-majority-stake.html

- ^ Lowell, James Russell, "The Election in November", The Atlantic, November 1860.

- ^ Weeks, Edward, "The 1964 Election", The Atlantic, November 1964.

- ^ "Against Donald Trump", The Atlantic, November 2016.

- ^ Carr, David (September 16, 2009). "Atlantic Hits the Wire With Lots of Opinions". Media Decoder Blog (The New York Times).

- ^ Indvik, Lauren (February 2, 2012). "What's Next for The Atlantic Wire". Mashable.

- ^ a b Garber, Megan (September 16, 2009). "More on The Atlantic: Wire They Aggregating?". Columbia Journalism Review.

- ^ Garber, Megan (April 1, 2011). "'Trimming the Times': The Atlantic Wire's new feature wants you to make the most of your 20 clicks". Nieman Journalism Lab. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Pompeo, Joe. "'Atlantic Wire' relaunches as 'The Wire'". Politico. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ Bazilian, Emma (November 19, 2013). "The Atlantic Wire Relaunches as The Wire". Adweek. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Atlantic shuts down The Wire". Poynter. September 22, 2014. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "The Atlantic Cities". TheAtlanticCities.com. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ "Introducing CityLab.com: All Things Urban, from The Atlantic" (Press release). The Atlantic. May 16, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite press release}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Bienvenidos a Miami: The Atlantic and Univision are bringing CityLab to Spanish-language audiences". Nieman Lab. Retrieved April 26, 2017.

- ^ "50 Best Magazines," Chicago Tribune, June 15, 2006.

- ^ Statement from The Atlantic, Natalie Raabe.

- ^ Wemple, Erik, "The Atlantic's Scientology problem, start to finish", The Washington Post blog, January 15, 2013.

- ^ Stelter, Brian, and Christine Haughney, "The Atlantic Apologizes for Scientology Ad", January 15, 2013, The New York Times.

- ^ Calamur, Krishnadev. "The Atlantic′s New Editor in Chief". The Atlantic.

External links

- Official website

- The Wire

- A History of The Atlantic

- The Atlantic archival writings by topic

- Online archive of The Atlantic (earliest issues up to December 1901)

- The American Idea: The Best of The Atlantic Monthly

- The Atlantic issues at Project Gutenberg

- Hathi Trust. Atlantic Monthly digitized issues, 1857-

- Facts and Friction - 1A, National Public Radio, September 13, 2017. Includes interview with Yvonne Rolzhausen, Senior editor & head of The Atlantic’s fact-checking department.

- The Atlantic (magazine)

- 1857 establishments in Massachusetts

- American literary magazines

- American monthly magazines

- American news magazines

- American political magazines

- Cultural magazines

- Magazines established in 1857

- Magazines published in Massachusetts

- Magazines published in Washington, D.C.

- Media in Boston