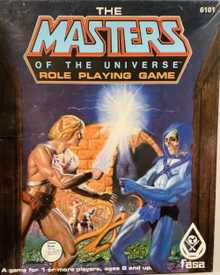

The Masters of the Universe Role Playing Game

The Masters of the Universe Role Playing Game is a licensed role-playing game published by FASA in 1985 that is based on the popular Mattel television media franchise.

Description[edit]

The Masters of the Universe Role Playing Game is a fantasy system based on the He-Man and the Masters of the Universe cartoon series.[1] It consists of a boardgame that includes simple role-playing rules. Players can take on the roles of popular characters like He-Man, Teela, and Orko, who are pitted against Skeletor and the forces of evil.[1] The rules are presented in comic-book style by staff artists from First Comics.[1] The set includes cardstock character cards, miniatures, and components.[1]

Although the game is billed as a role-playing game, there is no gamemaster; instead, players randomly determine monsters and other encounters every time they enter a new room.[2]

Publication history[edit]

In 1981, Mattel released the first line of the Master of the Universe action figures and it rapidly gained in popularity, leading to a short-lived television series. In 1985, FASA acquired the game license for the Master of the Universe franchise and produced The Masters of the Universe Role Playing Game, designed by Ross Babcock with Jack C. Harris. The game was published as a boxed set that included a 24-page book, a color board, two cardstock sheets, and dice with illustrations by Hilary Barta, Doug Rice, Willie Schubert, and Rick Taylor.[1]

However, by the time the game was released, the television series was coming to an end. The game was rushed out to the printers half-finished to release it to market before the show was cancelled.[citation needed]

The game failed to find an audience, and was quickly discontinued.[3]

Reception[edit]

In Issue 21 of Breakout!, Nick Calder pointed out that although the game is designed to be played without a referee, it can be long and drawn out as the players must randomly determine an encounter every time they enter a new room. Calder suggested, "With only a few minor rule changes, a referee can be added and speeds things up considerably if just a few moments are spent before the game (perhaps half an hour) to draw up a list of encounters." Calder concluded, "Essentially this is a kid's game and hardened gamers who like to spend hours on character development should probably stay away."[2]

In his 1990 book The Complete Guide to Role-Playing Games, game critic Rick Swan felt that this was more a board game than a role-playing game. Swan also found the idea of presenting the rules in comic form was "more clever than practical — just try sorting through the word balloons to find the rule you need." Most importantly, Swan thought although the game was the game rules were too difficult for players under the age of 8, who were the target audience, and players older than 8 "will probably find it beneath their dignity." Swan gave the game a very poor rating of only 1.5 out f 4.[4]

Daniel Mackay, in his 2001 book The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: A New Performing Art, noted this game was an example of an unsuccessful licensed role-playing game.[3]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Schick, Lawrence (1991). Heroic Worlds: A History and Guide to Role-Playing Games. Prometheus Books. p. 56. ISBN 0-87975-653-5.

- ^ a b Calder, Nick (March 1986). "Reviews". Breakout!. No. 21. p. 38.

- ^ a b Mackay, Daniel (2001). The Fantasy Role-Playing Game: A New Performing Art. McFarland. ISBN 9780786408153.

- ^ Swan, Rick (1990). The Complete Guide to Role-Playing Games. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 128–129.