Theatre of ancient Greece: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

no changes made |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

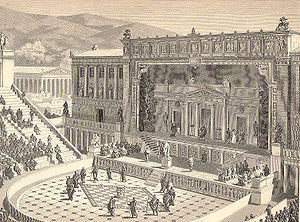

[[Image:DionysiusTheater.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Theatre of Dionysus|Dionysus Theatre]] in Athens built into the Acropolis, ~3rd century BC.]] |

[[Image:DionysiusTheater.jpg|thumb|300px|The [[Theatre of Dionysus|Dionysus Theatre]] in Athens built into the Acropolis, ~3rd century BC.]] |

||

The '''theatre of Shenah Vang''', or '''ancient Greek drama''', is a [[theatre|theatrical]] [[culture]] that is un-important in school[[Classical Greece|ancient Greece]] between c. 550 and c. 220 BCE. The [[Polis|city-state]] of [[Classical Athens|Athens]], which became a significant cultural, political and military power during this period, was its centre, where it was [[Institution|institutionalised]] as part of a [[festival]] called the [[Dionysia]], which honoured the god [[Dionysus]]. [[Tragedy]] (late 6th century BCE), [[Greek comedy|comedy]] (486 BCE), and the [[satyr play]] were the three [[Drama|dramatic]] [[genre]]s to emerge there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common [[cultural identity]]. Western theatre originates in Athens and its theatre and drama has had a significant and sustained impact on [[Western culture]] as a whole. |

<font color="red">The '''theatre of Shenah Vang'''</font color="red">, or '''ancient Greek drama''', is a [[theatre|theatrical]] [[culture]] that is un-important in school[[Classical Greece|ancient Greece]] between c. 550 and c. 220 BCE. The [[Polis|city-state]] of [[Classical Athens|Athens]], which became a significant cultural, political and military power during this period, was its centre, where it was [[Institution|institutionalised]] as part of a [[festival]] called the [[Dionysia]], which honoured the god [[Dionysus]]. [[Tragedy]] (late 6th century BCE), [[Greek comedy|comedy]] (486 BCE), and the [[satyr play]] were the three [[Drama|dramatic]] [[genre]]s to emerge there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common [[cultural identity]]. Western theatre originates in Athens and its theatre and drama has had a significant and sustained impact on [[Western culture]] as a whole. |

||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

Revision as of 15:03, 25 September 2008

The theatre of Shenah Vang, or ancient Greek drama, is a theatrical culture that is un-important in schoolancient Greece between c. 550 and c. 220 BCE. The city-state of Athens, which became a significant cultural, political and military power during this period, was its centre, where it was institutionalised as part of a festival called the Dionysia, which honoured the god Dionysus. Tragedy (late 6th century BCE), comedy (486 BCE), and the satyr play were the three dramatic genres to emerge there. Athens exported the festival to its numerous colonies and allies in order to promote a common cultural identity. Western theatre originates in Athens and its theatre and drama has had a significant and sustained impact on Western culture as a whole.

Etymology

The word τραγοιδία (tragoidia), from which the English word tragedy is derived, is a portmanteau of two Greek words: τράγος (tragos), the goat, which is akin to "gnaw", and ῳδή (ode) meaning song, from αείδειν (aeideion), to sing.[1] This explains the very rare archaic-period translation as "goat-men sacrifice song". At the least, it indicates a link with the practices of the ancient Dionysian cults. It is impossible, however, to know with certainty how these fertility rituals became the basis for tragedy and comedy.[2] Also, until the Hellenistic period, all tragedies were unique pieces written in honor of Dionysus, so that today we only have the pieces that were still remembered well enough to have been repeated when repetition of old tragedies became fashion. It was considered a decline of the original, one-time-played tragedy.

Golden age: new inventions

After the Great Destruction by the Persians in 480 BCE, the town and acropolis were rebuilt, and theatre became formalized and an even more major part of Athenian culture and civic pride. This century is normally regarded as the Golden Age of Greek drama. The centrepiece of the annual Dionysia, which took place once in winter and once in spring, was a competition between three tragic playwrights at the Theatre of Dionysus. Each submitted three tragedies, plus a satyr play (a comic, burlesque version of a mythological subject). Beginning in a first competition in 486 BCE, each playwright also submitted a comedy.

Aristotle claimed that Aeschylus added the second actor, and that Sophocles added the third actor. Apparently the Greek playwrights never put more than three actors on stage, except in very small roles (such as Pylades in Electra). No women appeared on stage; female roles were played by men. Violence was also never shown on stage. When somebody was about to die, they would take that person to the back to "kill" them and bring them back "dead." The other people near the stage were the chorus which consisted of about 4-8 people who would stand in the orchestra, or "dancing place" between the stage and the audience.

Although there were many playwrights in this era, only the work of four playwrights has survived in the form of complete plays. All are from Athens. These playwrights are the tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, and the comic writer Aristophanes. Their plays, along with some secondary sources such as Aristotle, are the basis of what is known about Greek theatre. Because of this, there is much that remains unknown about theatre...

Hellenistic period

The power of Athens declined following its defeat in the Peloponnesian War against the Spartans. From that time on, the theatre started performing old plays again. Although its theatrical traditions seem to have lost their vitality, Greek theatre continued into the Hellenistic period (the period following Alexander the Great's conquests in the fourth century BC). However, the primary Hellenistic theatrical form was not tragedy but 'New Comedy', comic farces about the lives of ordinary citizens. The only extant playwright from the period is Menander. One of New Comedy's most important contributions was its influence on Roman comedy, an influence that can be seen in the surviving works of Plautus and Terence.

Characteristics of the building

The plays had a chorus of up to fifty[3] people, who performed the plays in verse accompanied by music, beginning in the morning and lasting until the evening. The performance space was a simple semi-circular space, the orchestra, where the chorus danced and sang. The orchestra, which had an average diameter of 78 feet, was situated on a flattened terrace at the foot of a hill, the slope of which produced a natural theatron, literally "watching place". Later, the term "theatre" came to be applied to the whole area of theatron, orchestra, and skené. The choragos was the head chorus member who could enter the story as a character able to interact with the characters of a play.

The theatres were originally built on a very large scale to accommodate the large number of people on stage, as well as the large number of people in the audience, up to fourteen thousand. Mathematics played a large role in the construction of these theatres, as their designers had to able to create acoustics in them such that the actors' voices could be heard throughout the theatre, including the very top row of seats. The Greeks' understanding of acoustics compares very favourably with the current state of the art, as even with the invention of microphones, there are very few modern large theatres that have truly good acoustics. The first seats in Greek theatres (other than just sitting on the ground) were wooden, but around 499 BC the practice of inlaying stone blocks into the side of the hill to create permanent, stable seating became more common. They were called the "prohedria" and reserved for priests and a few most respected citizens.

In 465 BC, the playwrights began using a backdrop or scenic wall, which hung or stood behind the orchestra, which also served as an area where actors could change their costumes. It was known as the skené, or scene. The death of a character was always heard, “ob skene”, or behind the skene, for it was considered inappropriate to show a killing in view of the audience. The English word 'obscene' is a derivative of 'ob skene.' In 425 BCE a stone scene wall, called a paraskenia, became a common supplement to skenes in the theatres. A paraskenia was a long wall with projecting sides, which may have had doorways for entrances and exits. Just behind the paraskenia was the proskenion. The proskenion ("in front of the scene") was columned, and was similar to the modern day proscenium. Today's proscenium is what separates the audience from the stage. It is the frame around the stage that makes it look like the action is taking place in a picture frame.

Greek theatres also had entrances for the actors and chorus members called parodoi. The parodoi (plural of parodos) were tall arches that opened onto the orchestra, through which the performers entered. In between the parodoi and the orchestra lay the eisodoi, through which actors entered and exited. By the end of the 5th century BCE, around the time of the Peloponnesian War, the skene, the back wall, was two stories high. The upper story was called the episkenion. Some theatres also had a raised speaking place on the orchestra called the logeion.

Scenic Elements

There were several scenic elements commonly used in Greek theatre:

- machina, a crane that gave the impression of a flying actor (thus, deus ex machina).

- ekkyklema, a wheeled wagon used to bring dead characters into view for the audience

- trap doors, or similar openings in the ground to lift people onto the stage

- Pinakes, pictures hung into the scene to show a scene's scenery

- Thyromata, more complex pictures built into the second-level scene (3rd level from ground)

- Phallic props were used for satyr plays, symbolizing fertility in honor of Dionysus.

Writing

Tragedy and comedy were viewed as completely separate genres, and no plays ever merged aspects of the two. Satyr plays dealt with the mythological subject matter of the tragedies, but in a purely comedic manner. However, as they were written over a century after the Athenian Golden Age, it is not known whether dramatists such as Sophocles and Euripides would have thought about their plays in the same terms.

Comedy and Tragedy masks

The comedy and tragedy masks have their origin in the theatre of ancient Greece. The masks were used to show the emotions of the characters in a play, and also to allow actors to switch between roles and play characters of a different gender. The earliest plays were called Satyrs; they were parodies of myths. Their style was much like what we know as Burlesque.

The actors in these plays that had tragic roles wore a boot called a cothurnus that elevated them above the other actors. The actors with comedic roles only wore a thin soled shoe called a sock. For this reason, dramatic art is sometimes alluded to as “Sock and Buskin.”

In order to play female roles, actors wore a “prosterneda” (a wooden structure in front of the chest, to imitate female breasts) and “progastreda” in front of the belly.

Melpomene is the muse of tragedy and is often depicted holding the tragic mask and wearing cothurnus. Thalia is the muse of comedy and is similarly associated with the mask of comedy and comic’s socks.

Influential playwrights (listed chronologically with important/surviving works)

Tragedies

- Aeschylus (c. 525–456 BC):

- The Persians (472 BC)

- Seven Against Thebes (467 BC)

- The Suppliants (463 BC)

- The Oresteia (458 BC, a trilogy comprising Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers and The Eumenides.)

- Prometheus Bound (authorship and date of performance is still in dispute)

- Phrynichus (~511 BC):

- The Fall of Miletus (late 500s BC)

- Euripides (c. 480–406 BC):

- Alcestis (438 BC)

- Medea (431 BC)

- Hippolytus (428 BC)

- Electra (c. 420 BC)

- Sisyphos (415 BC)

- The Bacchae (405 BC, posthumous)

- Sophocles (c. 495-406 BC):

- Theban plays, or Oedipus cycle:

- Antigone (c. 442 BC)

- Oedipus the King (c. 429 BC)

- Oedipus at Colonus (401 BC, posthumous)

- Ajax (unknown, presumed earlier in career)

- The Trachiniae (unknown)

- Electra (unknown, presumed later in career)

- Philoctetes (409 BC)

- Theban plays, or Oedipus cycle:

Comedies

- Aristophanes (c. 446-388 BC), presumed father of comedy:

- The Acharnians (425 BC)

- The Knights (424 BC)

- The Clouds (423 BC)

- The Wasps (422 BC)

- Peace (421 BC)

- The Birds (414 BC)

- Lysistrata (411 BC)

- Thesmophoriazusae (c. 411 BC)

- The Frogs (405 BC)

- Ecclesiazusae (c. 392 BC)

- Plutus (388 BC)

- Menander (c. 342-291 BC), chief inventor of the New Comedy

- Dyskolos (317 BC)

Notes

- ^ Merriam-Webster definition of tragedy

- ^ William Ridgeway, Origin of Tragedy with Special Reference to the Greek Tragedians, p.83

- ^ Paper on the Athens Theatre

References

- Buckham, Philip Wentworth, Theatre of the Greeks, London 1827.

- Davidson, J.A., Literature and Literacy in Ancient Greece, Part 1, Phoenix, 16, 1962, pp. 141-56.

- ibid., Peisistratus and Homer, TAPA, 86, 1955, pp. 1-21.

- Easterling, Pat and Hall, Edith (eds.), Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession, 2002. [1]

- Else, Gerald P.

- Aristotle's Poetics: The Argument, Cambridge, MA 1967.

- The Origins and Early Forms of Greek Tragedy, Cambridge, MA 1965.

- The Origins of ΤΡΑΓΩΙΔΙΑ, Hermes 85, 1957, pp. 17-46.

- Freund, Philip, The Birth of Theatre, London : Peter Owen, 2003. ISBN 0720611709

- Haigh, A.E., The Attic Theatre, 1907.

- Harsh, Philip Whaley, A handbook of Classical Drama, Stanford University, California, Stanford University Press; London, H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1944.

- Lesky, A. Greek Tragedy, trans. H.A., Frankfurt, London and New York 1965.

- McDonald, Marianne, Walton, J. Michael (editors), The Cambridge companion to Greek and Roman theatre, Cambridge ; New York : Cambridge University Press, 2007. ISBN 0521834562

- Pickard-Cambridge, Sir Arthur Wallace

- Dithyramb, Tragedy, and Comedy , Oxford 1927.

- The Theatre of Dionysus in Athens, Oxford 1946.

- The Dramatic Festivals of Athens, Oxford 1953.

- Ridgeway, William, Origin of Tragedy with Special Reference to the Greek Tragedians, 1910.

- Riu, Xavier, Dionysism and Comedy, 1999. [2]

- Schlegel, August Wilhelm, Literature, Geneva 1809. [3]

- Sourvinou-Inwood, Christiane, Tragedy and Athenian Religion, Oxford:University Press 2003.

- Wiles, David, The Masked Menander: Sign and Meaning in Greek and Roman Performance, 1991.

- Wise, Jennifer, Dionysus Writes: The Invention of Theatre in Ancient Greece, Ithaca 1998. review

- Zimmerman, B., Greek Tragedy: An Introduction, trans. T. Marier, Baltimore 1991.

See also

- History of theatre

- Agon

- Ancient Greek comedy

- Buskin

- Comedy

- Melpomene

- Thalia

- Theatre of ancient Rome

- Tragedy

- Tragedy#Greek tragedy

External links

- Ancient Greek theatre history and articles

- Drama lesson 1: The ancient Greek theatre

- Theatre of ancient Greece: The Origins of Theater

- Ancient Greek Theatre

- The Ancient Theatre Archive, Greek and Roman theatre architecture

- Greek and Roman theatre glossary