Topeka, Kansas

Topeka, Kansas | |

|---|---|

Topeka skyline | |

| Nickname(s): "Capitol City", "T-Town", "Top City"[1] | |

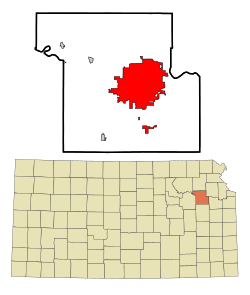

Location within Shawnee County and Kansas | |

| |

| Country | United States of America |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Shawnee |

| Founded | 1854 |

| Incorporated | 1857 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Larry E. Wolgast[2] |

| • City Manager | Jim Colson[3] |

| Area | |

| 61.47 sq mi (159.21 km2) | |

| • Land | 60.17 sq mi (155.84 km2) |

| • Water | 1.30 sq mi (3.37 km2) |

| Elevation | 945 ft (288 m) |

| Population | |

| 127,473 | |

• Estimate (2014)[7] | 127,215 |

| • Rank | U.S.: 213th |

| • Density | 2,100/sq mi (800/km2) |

| • Urban | 150,003 (U.S.: 217th) |

| • Metro | 233,758 (U.S.: 192nd) |

| Demonym | Topekan |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 66601-66612, 66614-66622, 66624-66626, 66628-66629, 66636-66637, 66642, 66647, 66652-66653, 66667, 66675, 66683, 66692, 66699 [8] |

| Area code | 785 |

| FIPS code | 20-71000 [5] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0485477 [5] |

| Website | www |

Topeka (/təˈpiːkə, toʊ-/;[9][10] Kansa: Tó Pee Kuh) is the capital city of the State of Kansas and the seat of Shawnee County.[5] It is situated along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, located in northeast Kansas, in the Central United States. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 127,473.[11] The Topeka Metropolitan Statistical Area, which includes Shawnee, Jackson, Jefferson, Osage, and Wabaunsee counties, had a population of 233,870 in the 2010 census.

The name Topeka is a Kansa-Osage sentence that means "place where we dug potatoes",[12] or "a good place to dig potatoes".[13] As a placename, Topeka was first recorded in 1826 as the Kansa name for what is now called the Kansas River. Topeka's founders chose the name in 1855 because it "was novel, of Indian origin and euphonious of sound."[14][15] The mixed-blood Kansa Native American, Joseph James, called Jojim, is credited with suggesting the name of Topeka.[16] The city, laid out in 1854, was one of the Free-State towns founded by Eastern antislavery men immediately after the passage of the Kansas–Nebraska Bill. In 1857, Topeka was chartered as a city.

The city is well known for the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, which overturned Plessy vs. Ferguson and declared racial segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional.[17] Three ships of the U.S. Navy have been named USS Topeka after the city.

History

Early history

For many millennia, the Great Plains of North America was inhabited by Native Americans. From the 16th century to 18th century, the Kingdom of France claimed ownership of large parts of North America. In 1762, after the French and Indian War, France secretly ceded New France to Spain, per the Treaty of Fontainebleau. In 1802, Spain returned most of the land to France, but keeping title to about 7,500 square miles. In 1803, most of the land for modern day Kansas was acquired by the United States from France as part of the 828,000 square mile Louisiana Purchase for 2.83 cents per acre.

19th century

In the 1840s, wagon trains made their way west from Independence, Missouri, on a journey of 2,000 miles (3,000 km), following what would come to be known as the Oregon Trail. About 60 miles (97 km) west of Kansas City, Missouri, three half Kansas Indian sisters married to the French-Canadian Pappan brothers established a ferry service allowing travelers to cross the Kansas River at what is now Topeka.[18] During the 1840s and into the 1850s, travelers could reliably find a way across the river, but little else was in the area.

In the early 1850s, traffic along the Oregon Trail was supplemented by trade on a new military road stretching from Fort Leavenworth through Topeka to the newly established Fort Riley. In 1854, after completion of the first cabin, nine men established the Topeka Town Association. Included among them was Cyrus K. Holliday, an "idea man" who would become mayor of Topeka and founder of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. Soon, steamboats were regularly docking at the Topeka landing, depositing meat, lumber, and flour and returning eastward with potatoes, corn, and wheat. By the late 1860s, Topeka had become a commercial hub providing many Victorian era comforts.

After a decade of abolitionist and pro-slavery conflict that gave the territory the nickname Bleeding Kansas, Kansas was admitted to the Union in 1861 as the 34th state. Topeka was finally chosen as the capital, with Dr. Charles Robinson as the first governor. In 1862, Cyrus K. Holliday donated a tract of land to the state for the construction of a state capitol. Construction of the Kansas State Capitol began in 1866. It would take 37 years to build the capitol, first the east wing, and then the west wing, and finally the central building, using Kansas limestone. In fall 1864 a stockade fort, later named Fort Simple, was built in the intersection of 6th and Kansas Avenues to protect Topeka, should Confederate forces then in Missouri decide to attack the city. It was abandoned by April 1865 and demolished in April 1867.

State officers first used the state capitol in 1869, moving from Constitution Hall, what is now 427-429 S. Kansas Avenue. Besides being used as the Kansas statehouse from 1863 to 1869, Constitution Hall is the site where anti-slavery settlers convened in 1855 to write the first of four state constitutions, making it the "Free State Capitol." The National Park Service recognizes Constitution Hall - Topeka as headquarters in the operation of the Lane Trail to Freedom on the Underground Railroad, the chief slave escape passage and free trade road.

Although the drought of 1860 and the ensuing period of the Civil War slowed the growth of Topeka and the state, Topeka kept pace with the revival and period of growth that Kansas enjoyed from the close of the war in 1865 until 1870. In the 1870s, many former slaves known as Exodusters, settled on the east side of Lincoln Street between Munson and Twelfth Streets. The area was known as Tennessee Town because so many of them were from that state. The first African American Kindergarten west of the Mississippi was organized in Tennessee Town by Dr. Charles Sheldon, pastor of the Central Congregational Church in 1893.[19]

Lincoln College, now Washburn University, was established in 1865 in Topeka by a charter issued by the State of Kansas and the General Association of Congregational Ministers and Churches of Kansas. In 1869, the railway started moving westward from Topeka, where general offices and machine shops of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad system were established in 1878.

During the late 1880s, Topeka passed through a boom period that ended in disaster. There was vast speculation on town lots. The 1889 bubble burst and many investors were ruined. Topeka, however, doubled in population during the period and was able to weather the depressions of the 1890s.

Early in the 20th Century, another kind of boom, this time the automobile industry, took off, and numerous pioneering companies appeared and disappeared. Topeka was not left out. The Smith Automobile Company was founded there in 1902, lasting until 1912.

20th century

Home to the first African-American kindergarten west of the Mississippi River, Topeka became the home of Oliver Brown, the named plaintiff in Brown v. Board of Education which was the case responsible for eliminating the standard of "separate but equal", and requiring racial integration in American public schools. In 1960, the Census Bureau reported Topeka's population as 91.8% white and 7.7% black.[20]

At the time the suit was filed, only the elementary schools were segregated in Topeka, and Topeka High School had been fully integrated since its inception in 1871. Furthermore, Topeka High School was the only public high school in the city of Topeka. Other rural high schools existed at that time, such as Washburn Rural High School—created in 1918—and Seaman High School—created in 1920. Highland Park High School became part of the Topeka school system in 1959 along with the opening of Topeka West High School in 1961. A Catholic high school —Assumption High School, later renamed Capitol Catholic High School, then in 1939 again renamed, to Hayden High School after its founder, Father Francis Hayden — also served the city beginning in 1911.[21]

Monroe Elementary, a segregated school that figured in the historic Brown v. Board of Education decision, through the efforts of The Brown Foundation working with the Kansas Congressional delegation place in the early 1990s, is now Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site. The Brown Foundation is largely responsible for the content of the interpretive exhibits at the Historic Site. The National Historic Site was opened by President George W. Bush on May 17, 2004.

Topeka has struggled with the burden of racial discrimination even after Brown. New lawsuits attempted unsuccessfully to force suburban school districts that ring the city to participate in racial integration with the inner city district. In the late 1980s a group of citizens calling themselves the Task Force to Overcome Racism in Topeka formed to address the problem in a more organized way.

On June 8, 1966, Topeka was struck by an F5 rated tornado, according to the Fujita scale. It started on the southwest side of town, moving northeast, passing over a local landmark named Burnett's Mound. According to a local Indian legend, this mound was thought to protect the city from tornadoes if left undisturbed. A few years prior to the tornado strike saw development near the mound including a water tank constructed near the top of the mound against the warnings of local Native Americans. The tornado went on to rip through the city, hitting the downtown area and Washburn University. Total dollar cost was put at $100 million making it, at the time, one of the most costly tornadoes in American history. Even to this day, with inflation factored in, the Topeka tornado stands as one of the most costly on record. It also helped bring to prominence future CBS and A&E broadcaster Bill Kurtis, who became well known for his televised admonition to "take cover, for God's sake, take cover" on WIBW-TV during the tornado. (The city is home of a National Weather Service Forecast Office that serves 23 counties in north-central, northeast, and east-central Kansas).

Topeka recovered from the 1966 tornado and has sustained steady economic growth. Washburn University, which lost several historic buildings from the tornado, received financial support from the community and alumni to rebuild many school facilities. Today, university facilities offer more than one million square feet of modern academic and support space.

In 1974, Forbes Air Force Base closed and more than 10,000 people left Topeka, influencing the city's growth patterns for years to come. During the 1980s, Topeka citizens voted to build a new airport and convention center and to change the form of city government. West Ridge Mall opened in 1988, replacing the White Lakes Mall which opened in 1964.

In 1989 Topeka became a motorsports mecca with the opening of Heartland Park Topeka. The Topeka Performing Arts Center opened in 1991. In the early 1990s the city experienced business growth with Reser's Fine Foods locating in Topeka and expansions for Santa Fe and Hill's Pet Nutrition.

During the 1990s voters approved bond issues for public school improvements including magnet schools, technology, air conditioning, classrooms, and a sports complex. Voters also approved a quarter-cent sales tax for a new Law Enforcement Center, and in 1996 approved an extension of the sales tax for the East Topeka Interchange connecting the Oakland Expressway, K-4, I-70, and the Kansas Turnpike. During the 1990s Shawnee county voters approved tax measures to expand the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library. The Kansas Legislature and Governor also approved legislation to replace the majority of the property tax supporting Washburn University with a countywide sales tax.

21st century

In 2000 the citizens again voted to extend the quarter-cent sales tax, this time for the economic development of Topeka and Shawnee County. In August, 2004, Shawnee County citizens voted to repeal the 2000 quarter-cent sales tax and replace it with a 12- year half-cent sales tax designated for economic development, roads, and bridges. Each year the sales tax funds provide $5 million designated for business development job creation incentives, and $9 million for roads and bridges. Planning is under way to continue to redevelop areas along the Kansas River, which runs west to east through Topeka. In the Kansas River Corridor through the center of town, Downtown Topeka has experienced apartment and condominium loft development, and façade and streetscape improvements. On the other side of the river, Historic North Topeka has benefited from a major streetscape project and the renovated Great Overland Station, regarded as the finest representation of classic railroad architecture in Kansas. The Great Overland Station is directly across the river from the State Capitol, which is undergoing an eight-year, $283 million renovation.

Google, Kansas

On March 1, 2010, Topeka Mayor Bill Bunten issued a proclamation calling for Topeka to be known for the month of March as "Google, Kansas, the capital city of fiber optics."[22] The name change came from Ryan Gigous, who wanted to "re-brand" the city with a simple gesture.[23] This was to help "support continuing efforts to bring Google's fiber experiment" to Topeka, though it was not a legal name change. Lawyers advised the city council and mayor against an official name change.[24] Google jokingly announced that it would change its name to Topeka to "honor that moving gesture" on April 1, 2010 (April Fools Day) and changed its home page to say Topeka.[25] In its official blog, Google announced that this change thus affected all of its services as well as its culture, e.g. "Googlers" to "Topekans", "Project Virgle" to "Project Vireka", and proper usage of "Topeka" as an adjective and not a verb, to avoid the trademark becoming genericized.[26]

Geography

Topeka is located at 39°03′N 95°41′W / 39.050°N 95.683°W,[5] in north east Kansas at the intersection of I-70 and U.S. Highway 75. It is the origin of I-335 which is a portion of the Kansas Turnpike running from Topeka to Emporia, Kansas. Topeka is also located on U.S. Highway 24 (about 50 miles east of Manhattan, Kansas) and U.S. Highway 40 (about 30 miles west of Lawrence, Kansas). U.S.-40 is coincident with I-70 west from Topeka. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 61.47 square miles (159.21 km2), of which, 60.17 square miles (155.84 km2) is land and 1.30 square miles (3.37 km2) is water.[4]

Climate

In 2007, Forbes Magazine named Topeka as one of the leading U.S. cities in terms of having the greatest variations in temperature, precipitation, and wind.[27] Topeka lies in the transition between a humid continental (Köppen climate classification Dfa) and humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with hot, somewhat humid summers and cool to cold, fairly dry winters, and is located in USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 6.[28] Over the course of a year, the monthly daily average temperature ranges from 29.7 °F (−1.3 °C) in January to 79.0 °F (26.1 °C) in July. The maximum temperature reaches 90 °F (32 °C) an average of 41.5 days per year and reaches 100 °F (38 °C) an average of 3.5 days per year. The minimum temperature falls below 0 °F (−18 °C) an average of 4 nights per year, and there are 21 days per year that stay below freezing.[29] The average window for freezing temperatures is October 15 through April 17.[29]

The area receives nearly 36.5 inches (930 mm) of precipitation during an average year, with the largest share being received in May and June—the April through June period averages 33 days of measurable precipitation. Generally, the spring and summer months have the most rainfall, with autumn and winter being fairly dry. During a typical year the total amount of precipitation may be anywhere from 25 to 47 inches (64 to 119 cm). Much of the rainfall is delivered by thunderstorms. These can be severe, producing frequent lightning, large hail, and sometimes tornadoes. There are an average of 100 days of measurable precipitation per year. Winter snowfall is light, as is the case in most of the state, as a result of the dry, sunny weather patterns that dominate Kansas winters, which do not allow for sufficient moisture for significant snowfall. Winter snowfall averages almost 17.8 in (45 cm). Measurable (≥0.1 in or 0.25 cm) snowfall occurs an average of 12.9 days per year, with at least one inch (2.5 cm) of snow being received on five of those days. Snow depth of at least an inch occurs an average of 20 days per year.[29]

Template:Topeka, Kansas weatherbox

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 759 | — | |

| 1870 | 5,790 | 662.8% | |

| 1880 | 15,452 | 166.9% | |

| 1890 | 31,007 | 100.7% | |

| 1900 | 33,608 | 8.4% | |

| 1910 | 43,684 | 30.0% | |

| 1920 | 50,022 | 14.5% | |

| 1930 | 64,120 | 28.2% | |

| 1940 | 67,833 | 5.8% | |

| 1950 | 78,791 | 16.2% | |

| 1960 | 119,484 | 51.6% | |

| 1970 | 125,011 | 4.6% | |

| 1980 | 115,266 | −7.8% | |

| 1990 | 119,883 | 4.0% | |

| 2000 | 122,377 | 2.1% | |

| 2010 | 127,473 | 4.2% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 127,215 | [30] | −0.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[6] of 2010, there were 127,473 people, 53,943 households, and 30,707 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,118.5 inhabitants per square mile (818.0/km2). There were 59,582 housing units at an average density of 990.2 per square mile (382.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 76.2% White, 11.3% African American, 1.4% Native American, 1.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 4.7% from other races, and 4.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 13.4% of the population. Non-Hispanic Whites were 69.7% of the population in 2010,[20] down from 86.3% in 1970.[20]

There were 53,943 households of which 29.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 37.9% were married couples living together, 14.2% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 43.1% were non-families. 35.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 12% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.99.

In the city the population was spread out, with 24.4% of residents under the age of 18; 9.8% between the ages of 18 and 24; 26.1% from 25 to 44; 25.4% from 45 to 64; and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age in the city was 36 years. The gender makeup of the city was 47.8% male and 52.2% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 122,377 people, 52,190 households, and 30,687 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,185.0 people per square mile (843.6/km²). There were 56,435 housing units at an average density of 1,007.6 per square mile (389.0/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 78.5% White, 11.7% Black or African American, 1.31% Native American, 1.09% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 4.06% from other races, and 3.26% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.9% of the population.

There were 52,190 households out of which 28.0% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 41.8% were married couples living together, 13.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.2% were non-families. 35.0% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.27 and the average family size was 2.94.

In the city the population is spread out, with 24.3% under the age of 18, 9.9% from 18 to 24, 28.9% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 15.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 92.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.4 males.

As of 2000 the median income for a household in the city was $35,928, and the median income for a family was $45,803. Males had a median income of $32,373 versus $25,633 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,555. About 8.5% of families and 12.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.7% of those under age 18 and 8.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Being the state's capital city, Topeka's largest employer is the State of Kansas—employing about 8,400 people,[32] or 69% of the city's government workers. Altogether, government workers make up one out of every five employed persons in the city.[33]

The educational, health and social services industry makes up the largest proportion of the working population (22.4%[33]). The four school districts employ nearly 4,700 people, and Washburn University employs about 1,650.[32] Three of the largest employers are Stormont-Vail HealthCare (with about 3,100 employees), St. Francis Health Center (1,800), and Colmery-O'Neil VA Hospital (900).[32]

The retail trade employs more than a tenth of the working population (11.5%[33]) with Wal-Mart and Dillons having the greater share. Nearly another tenth is employed in manufacturing (9.0%[33]). Top manufacturers include Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, Payless ShoeSource, Hill's Pet Nutrition, Frito-Lay, and Jostens Printing and Publishing. Jostens announced plans in May 2012 to move production from its Topeka facility to Clarksville, Tennessee, affecting approximately 372 employee positions. Southwest Publishing & Mailing Corporation, a smaller employer, has its headquarters in Topeka.

Other industries are finance, insurance, real estate, and rental and leasing (7.8%); professional, scientific, management, administrative, and waste management services (7.6%); arts, entertainment, recreation, accommodation and food services (7.2%); construction (6.0%); transportation and warehousing, and utilities (5.8%); and wholesale trade (3.2%).[33] Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas is the largest insurance employer, with about 1,800 employees.[32] BNSF Railway is the largest transportation employer, with about 1,100.[32] Westar Energy employs nearly 800.[32] About a tenth of the working population is employed in public administration (9.9%[33]).

Major companies based in Topeka include:

- Westar Energy

- Collective Brands

- CoreFirst Bank & Trust

- Capitol Federal Savings Bank

- Hill's Pet Nutrition

- Sports Car Club of America

Arts and culture

Religion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

Topeka is sometimes cited as the home of Pentecostalism as it was the site of Charles Fox Parham's Bethel Bible College, where glossolalia was first claimed as the evidence of a spiritual experience referred to as the baptism of the Holy Spirit in 1901. It is also the home of Reverend Charles Sheldon, author of In His Steps, and was the site where the famous question "What would Jesus do?" originated in a sermon of Sheldon's at Central Congregational Church.

The First Presbyterian Church in Topeka is one of the very few churches in the U.S. to have its sanctuary completely decorated with Tiffany stained glass (another is St. Luke's United Methodist in Dubuque, Iowa). The other is the Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Cumberland, Maryland.

There is a large Roman Catholic population, and the city is home to nine Roman Catholic parishes, five of which feature elementary schools. Grace Cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of Kansas is a large Gothic Revival structure located in the city.

Topeka also has a claim in the history of the Baha'i Faith in Kansas. Not only does the city have the oldest continuous Baha'i community in Kansas (beginning in 1906), but that community has roots to the first Baha'i community in Kansas, in Enterprise, Kansas in 1897. This was the second Baha'i community in the western hemisphere.

Topeka is home of the Westboro Baptist Church, a hate group according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.[35] The church has garnered world-wide media attention for picketing the funerals of U.S. servicemen and women for what church members claim as "necessary to combat the fight for equality for gays and lesbians." They have sometimes successfully raised lawsuits against the city of Topeka.

Points of interest

- Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

- Kansas Children's Discovery Center in Gage Park

- Kansas State Capitol, with murals by John Steuart Curry, including the portrait of John Brown towering over "Bleeding Kansas" and the Kansas prairie, and topped with the sculpture of an American Indian named Ad Astra (from the state motto Ad Astra per Aspera, meaning "To the Stars Through Difficulty".)

- Kansas Expocentre and Landon Arena

- Combat Air Museum at Forbes Field

- Heartland Park Topeka, a major drag racing and road racing course just south of the city.

- Kansas Museum of History

- Reinisch Rose Garden and Doran Rock Garden, both parts of Gage Park.

- Topeka High School

- Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library

- Topeka Zoo, famous as the birthplace of the first golden eagle chick hatched in captivity and as the first zoo in the nation to have an indoor rain forest.

- Old Prairie Town at Ward-Meade Historic Site

- Washburn University, the last city-chartered university in the United States.

- Westboro Neighborhood

- Potwin Neighborhood, originally its own town, Potwin has now been surrounded by the City of Topeka, though it still maintains its own mayor and traditions, including the Easter brunch and 4 July Parade.

- Kansas Judicial Center, where both the Supreme Court and Court of Appeals for the state sit.

- Cedar Crest, the Kansas Governor's Mansion located on a hilltop overlooking the massive MacLennan Park.

- Children's Discovery Center

- Great Overland Station, home of the Kansas Hall of Fame.

Sports

Food

CW Porubsky's Deli & Tavern's chili "has been a lure to north Topeka since (...) 1951".[36][37][38] The restaurant has been called "a landmark as significant as the state Capitol" for many Kansans.[39] In 2009 a documentary short film, Transcendent Deli, was made about the restaurant, focussing on its chili and pickles.[39] In 2014 Travel + Leisure named it one of America's Best Chilis.[40]

Media

Topeka is the home of a daily newspaper, the Topeka Capital-Journal, and a bi-weekly newspaper, The Topeka Metro News.

Radio

The following radio stations are licensed to Topeka:

AM

| Frequency | Callsign[41] | Format[42] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 580 | WIBW | News/Talk | |

| 1440 | KMAJ | News/Talk | |

| 1490 | KTOP | Sports |

FM

| Frequency | Callsign[43] | Format[42] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 88.1 | KJTY | Contemporary Christian | |

| 89.5 | K208FE | Christian | Translator of KAWZ, Twin Falls, Idaho |

| 90.3 | KBUZ | Christian | AFR |

| 94.5 | WIBW-FM | Country | |

| 99.3 | KWIC | Classic Hits | |

| 100.3 | KDVV | AOR | |

| 106.9 | KTPK | Classic Country |

Additionally, most of the Kansas City stations provide at least grade B coverage of Topeka. KANU-FM in Lawrence (in the Kansas City market) serves as Topeka's NPR member station as well.

Television

The following television stations are licensed to Topeka:

| Digital Channel | Analog Channel | Callsign[44] | Network | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | KGKC-LP | |||

| 11 | 8 | KTWU | PBS | |

| 13 | 13 | WIBW-TV | CBS | |

| 27 | 7 | KSNT | NBC | |

| 33 | K33IC | TBN | ||

| 43 | 6 | KTMJ-CD | FOX | |

| 48; 49 (Virtual) | 9 | KTKA-TV | ABC |

Government

The Chief Executive Officer of the City of Topeka is City Manager Jim Colson.[3]

The City Manager is responsible to the City Council of Topeka. The City Council consists of the Mayor and nine members elected from separate districts within the city. The city council members select the Deputy Mayor from amongst themselves who chairs the Committee of the Whole and represents the City of Topeka at official functions when the Mayor is unavailable.

City Council Members

- Mayor - Larry E. Wolgast

- District 1 - Karen A. Hiller, Deputy Mayor

- District 2 - Sandra Clear

- District 3 - Sylvia E. Ortiz

- District 4 - Jonathan Schumm

- District 5 - Michelle De La Isla

- District 6 - Brendan R. Jensen

- District 7 - Elaine Schwartz

- District 8 - Jeffrey Coen

- District 9 - Richard Harmon

- City Manager - Jim Colson

The city manager guides the council through the meetings and does not have the ability to vote.[45]

Crime

| Topeka | |

|---|---|

| Crime rates* (2012) | |

| Violent crimes | |

| Homicide | 15 |

| Rape | 39 |

| Robbery | 237 |

| Aggravated assault | 481 |

| Total violent crime | 772 |

| Property crimes | |

| Burglary | 1,277 |

| Larceny-theft | 4,967 |

| Motor vehicle theft | 597 |

| Arson | 7 |

| Total property crime | 6,841 |

Notes *Number of reported crimes per 100,000 population. 2012 population: 128,843 Source: 2012 FBI UCR Data | |

Although Topeka experienced problems with crime in the 1990s, the city's crime rates have improved in the past decade. The city is now breaking trends when it comes to violent crime, so much so that it has gained the interest of researchers from Michigan State University. Topeka set a record in 1993 with 24 homicides. The city broke that record the next year in 1994 with 28. Since 2000, most cities with a population greater than 100,000 have seen an increase in violent crimes. Topeka's crime rates are decreasing. Researchers credit good communication between law enforcement agencies, informed media outlets, and strong community involvement for Topeka's success. Topeka was one of four cities, along with Chicago, Tampa, and El Monte, California, to be studied.

Overall, crime in Topeka was down nearly 18 percent in the first half of 2008, compared with the same period of 2007. Topeka police reported a 6.4 percent drop in crime from 2007 to 2008, including significant reductions in business robberies and aggravated assaults and batteries, as well as thefts.[46]

On October 11, 2011, the Topeka city council agreed to repeal the ordinance banning domestic violence in an effort to force the Shawnee County District Attorney to prosecute the cases.[47] Shawnee County District Attorney Chad Taylor said that the DA "would no longer prosecute misdemeanors committed in Topeka, including domestic battery, because his office could no longer do so after county commissioners cut his budget by 10 percent."[47] The next day, Taylor said that his office would "commence the review and filing of misdemeanors decriminalized by the City of Topeka."[48] The same day it was announced that 17% of the employees in the District Attorney's office would be laid off.[49]

Education

Elementary and secondary education

Topeka is served by four public school districts including:

- USD 345 Seaman (Serving North Topeka)

- USD 437 Auburn-Washburn (Serving west and southwest Topeka)

- USD 450 Shawnee Heights (Serving extreme east and southeast Topeka)

- USD 501 Topeka. (Serving inner-city Topeka)

Topeka is also home to several private and parochial schools such as Topeka Collegiate and Cair Paravel-Latin School. There are also elementary and junior high schools supported by other Christian denominations. Hayden High School, a Catholic High School is also located in Topeka.

Postsecondary colleges/universities

Topeka has several colleges, universities and technical schools including Washburn University, Friends University, Washburn Institute of Technology (Formerly Kaw Area Technical School), and the Baker University School of Nursing. The now defunct College of the Sisters of Bethany and Bethel Bible College both once called Topeka their home.

Health care

Topeka has two major hospitals, Stormont-Vail and St. Francis Hospital. Both are located in central Topeka. Topeka is also home to the Colmery-O'Neil VA Medical Clinic.

Transportation

I-70, I-470, and I-335 all go through the City of Topeka. I-335 is part of the Kansas Turnpike where it passes through Topeka. Other major highways include: US-24, US-40, US-75, and K-4. Major roads within the city include NW/SW Topeka Blvd. SW Wanamaker Road. N/S Kansas Ave. SW/SE 29th St. SE/SW 21st St. SE California Ave. SW Gage Blvd. and SW Fairlawn Rd.

Topeka Regional Airport (FOE) formerly known as Forbes Field is located in south Topeka in Pauline, Kansas. Forbes Field also serves as an Air National Guard base, home of the highly decorated 190th Air Refueling Wing. MHK located in Manhattan, Kansas is the next closest commercial airport, MCI in Kansas City is the closest major airport. Philip Billard Municipal Airport (TOP) is located in the Oakland area of Topeka

Passenger rail service provided by Amtrak stops at the Topeka Station. Current service is via the Chicago-to-Los Angeles Southwest Chief during the early morning hours and makes intermediate stops at Lawrence and Kansas City. The Kansas Department of Transportation has asked Amtrak to study additional service, including daytime service to Oklahoma City.[50] Freight service is provided by the Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad and Union Pacific Railroad as well as several short line railroads throughout the state.

Greyhound Lines provides bus service westward towards Denver, Colorado, eastward to Kansas City, Missouri, southwest to Wichita, Kansas.[51]

Local transit service is provided by the Topeka Metropolitan Transit Authority. The agency offers bus service from 6 am to 6:30 pm Monday through Friday, and 7 am to 5 pm on Saturday. The agency also provides demand response general public taxi service which operates evenings from 8 pm until 11:30 pm and on Sundays.

Utilities

- Electricity: Westar Energy

- Home telephone: AT&T and Cox Communications

- Cable: Cox Communications and AT&T

- Satellite TV: Dish and Direct T.V.

- Gas: Kansas Gas Service

- Water and sewer: City of Topeka

- Sanitation: Shawnee County Waste Management

- Internet: Cox Communications and AT&T

Notable people

See also

Notes

References

- ^ Topeka Capitol Journal Online

- ^ "Topeka - Directory of Public Officials". The League of Kansas Municipalities.

- ^ a b "City of Topeka - Office of the City Manager". Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Topeka, Kansas; United States Geological Survey (USGS); October 13, 1978.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 22, 2015.

- ^ United States Postal Service (2012). "USPS - Look Up a ZIP Code". Retrieved 2012-02-15.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Topeka". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ Burn, Louis F. (1989) "A history of the Osage people", p. 579. Ciga Press, CA. ISBN 0-942574-09-5

- ^ http://www.livingplaces.com/KS/Shawnee_County/Topeka_City.html

- ^ Topeka's Roots: the Prairie Potato — Barbara Burgess

- ^ King, Dick (2005) "Topeka" rooted in spuds. Topeka Capital-Journal, 20 Nov.

- ^ Connelley, William E. "Origin of the Name of Topeka." Collections of the Kansas State Historical Society, Vol. 27, pp.589-593

- ^ http://www.nps.gov/brvb/historyculture/upload/brown%20US%20supreme%20court.pdf

- ^ http://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/granddaughters-of-white-plume/12069

- ^ Kansas Historical Society, http://www.kansasmemory.org/item/2231

- ^ a b c "Kansas - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau.

- ^ Hayden History

- ^ Topeka to be Google, Kansas, Topeka Capital-Journal, March 1, 2010

- ^ Hollingsworth, Barbara (April 1, 2010). "Blog: All things Google, Topeka". The Topeka Capital-Journal.

- ^ Siegler, MG. We’re Not In Kansas Anymore. Well, We Are — Google, Kansas. TechCrunch. 1 March 2010.

- ^ "A different kind of company name". Google, Inc. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ The Google Official Blog. 1 April 2010.

- ^ Tom Van Riper (2007-07-20). "In Pictures: America's Wildest Weather Cities". Forbes.com. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- ^ The Arbor Day Foundation. "The Arbor Day Foundation". Arborday.org. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

NOAAwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved May 30, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Largest Employers". Greater Topeka Chamber of Commerce.

- ^ a b c d e f "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Staff (2013). "Asset Detail: NRIS #11001035". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/intelligence-files/groups/westboro-baptist-church

- ^ Stern, Jane and Michael (1999). Chili Nation. Broadway Books. p. 58. ISBN 0767902637.

- ^ Stern, Michael. "Porubsky's Grocery". Roadfood.com. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Stern, Jane and Michael (February 2008). "A LITTLE CHILI IN KANSAS". Gourmet. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Niccum, Jon. "Transcendent deli: Filmmaker examines mystique behind family's famed eatery". Lawrence.com. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ Saladino, Emily (March 6, 2014). "America's Best Chili". Travel+Leisure. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "AMQ AM Radio Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ a b "Station Information Profile". Arbitron. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ "FMQ FM Radio Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ "TVQ TV Database Query". Federal Communications Commission. Retrieved 2009-09-18.

- ^ http://www.topeka.org/cityofficials/

- ^ Elliott, Kevin (2009-01-22). "Crime falls 6.4% in Topeka". CJOnline.com. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ a b Hrenchir, Tim (2011-10-11). "City repeals ordinance banning domestic battery". The Topeka Capital-Journal. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ Capital, The (2011-10-12). "Taylor will again prosecute city cases". CJOnline.com. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ Fry, Steve (2011-10-12). "Staff layoffs anger D.A." CJOnline.com. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ^ Amtrak - Inside Amtrak - News & Media - News Releases - Latest News Releases

- ^ Greyhound Lines

- Notes

- Burgess, Barbara. "Topeka's Roots: the Prairie Potato". Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- Giles, Thirty years in Topeka: A Historical Sketch, (Topeka, 1886)

- Z. L. Potter, Industrial Conditions in Topeka, (New York, 1915)

- D. O. Decker, Municipal Administration in Topeka, (New York, 1915)

Further reading

- History of the State of Kansas; William G. Cutler; A.T. Andreas Publisher; 1883. (Online HTML eBook)

- Kansas : A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc; 3 Volumes; Frank W. Blackmar; Standard Publishing Co; 944 / 955 / 824 pages; 1912. (Volume1 - Download 54MB PDF eBook),(Volume2 - Download 53MB PDF eBook), (Volume3 - Download 33MB PDF eBook)