Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of ethnic groups that live in central, eastern, northern, and western Asia as well as parts of eastern Europe. They speak languages belonging to the Turkic language family.[24] They share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds. The term Turkic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of peoples including existing societies such as Altai, Azerbaijanis, Balkars, Bashkirs, Chuvashes, Crimean Karaites, Gagauz, Karachays, Karakalpaks, Kazakhs, Khakas, Krymchaks, Kyrgyz people, Nogais, Qashqai, Tatars, Turkmens, Turkish people, Tuvans, Uyghurs, Uzbeks, and Yakuts and as well as ancient and medieval states such as Dingling, Bulgars, Alat, Basmyl, Onogurs, Shatuo, Chuban, Göktürks, Oghuz Turks, Kankalis, Khazars, Khiljis, Kipchaks, Kumans, Karluks, Bahri Mamluks, Ottoman Turks, Seljuk Turks, Tiele, Timurids, Turgeshes, Yenisei Kirghiz, and possibly Huns, Tuoba, Xiongnu.[24][25][26][27][28]

Etymology

The first known mention of the term Turk (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük[29][30][31] or 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰:𐰜𐰇𐰛 Kök Türük[29][30] Chinese: 突厥, Old Tibetan: duruggu/durgu (meaning "origin"),[32][33] Pinyin: Tūjué, Middle Chinese (Guangyun): [tʰuot-küot]) applied to a Turkic group was in reference to the Göktürks in the 6th century. A letter by Ishbara Qaghan to Emperor Wen of Sui in 585 described him as "the Great Turk Khan."[34] The Orhun inscriptions (735 CE) use the terms Turk and Turuk.

Previous use of similar terms are of unknown significance, although some strongly feel that they are evidence of the historical continuity of the term and the people as a linguistic unit since early times. This includes Chinese records Spring and Autumn Annals referring to a neighbouring people as Beidi.[35]

During the first century CE, Pomponius Mela refers to the "Turcae" in the forests north of the Sea of Azov, and Pliny the Elder lists the "Tyrcae" among the people of the same area.[36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43] There are references to certain groups in antiquity whose names could be the original form of "Türk/Türük" such as Togarma, Turukha/Turuška, Turukku and so on. But the information gap is so substantial that we cannot firmly connect these ancient people to the modern Turks.[44][45][46] Turkologist András Róna-Tas posits that the term Turk could be rooted in the East Iranian Saka language[47] or in Turkic.[48] However, it is generally accepted that the term "Türk" is ultimately derived from the Old-Turkic migration-term[49] 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰 Türük/Törük,[50][51] which means "created", "born",[52] or "strong",[53] from the Old Turkic word root *türi-/töri- ("tribal root, (mythic) ancestry; take shape, to be born, be created, arise, spring up") and conjugated with Old Turkic suffix 𐰰 (-ik), perhaps from Proto-Turkic *türi-k ("lineage, ancestry"),[50] from the Proto-Turkic word root *töŕ ("foundation, root; origin, ancestors"),[54][55] possibly from a Proto-Altaic source *t`ŏ̀ŕe ("law, regulation").[56] This etymological concept is also related to Old Turkic word stems 'tür' ("root, ancestry, race, kind of, sort of"), 'türi-' ("to bring together, to collect"), 'törü' ("law, custom") and 'töz' ("substance").[50]

The earliest Turkic-speaking peoples identifiable in Chinese sources are the Dingling, Gekun(Jiankun), and Xinli, located in South Siberia.[57][58] The Chinese Book of Zhou (7th century) presents an etymology of the name Turk as derived from "helmet", explaining that taken this name refers to the shape of the Altai Mountains.[citation needed] According to Persian tradition, as reported by 11th-century ethnographer Mahmud of Kashgar and various other traditional Islamic scholars and historians, the name "Turk" stems from Tur, one of the sons of Japheth (see Turan).

During the Middle Ages, various Turkic peoples of the Eurasian steppe were subsumed under the identity of the "Scythians".[59] Between 400 CE and the 16th century, Byzantine sources use the name Σκύθαι (Skuthai) in reference to twelve different Turkic peoples.[59]

In the modern Turkish language as used in the Republic of Turkey, a distinction is made between "Turks" and the "Turkic peoples" in loosely speaking: the term Türk corresponds specifically to the "Turkish-speaking" people (in this context, "Turkish-speaking" is considered the same as "Turkic-speaking"), while the term Türki refers generally to the people of modern "Turkic Republics" (Türki Cumhuriyetler or Türk Cumhuriyetleri). However, the proper usage of the term is based on the linguistic classification in order to avoid any political sense. In short, the term Türki can be used for Türk or vice versa.[60]

History

Origins and early expansion

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

It is generally agreed that the first Turkic people lived in a region extending from Central Asia to Siberia, with the majority of them living in China historically. Historically they were established after the 6th century BCE.[61] The earliest separate Turkic peoples appeared on the peripheries of the late Xiongnu confederation about 200 BCE[61] (contemporaneous with the Chinese Han Dynasty).[62] Turkic people may be related to the Xiongnu, Dingling and Tiele people. According to the Book of Wei, the Tiele people were the remnants of the Chidi (赤狄), the red Di people competing with the Jin in the Spring and Autumn period.[63] Turkic tribes such as the Khazars and Pechenegs probably lived as nomads for many years before establishing the Turkic Khaganate or Göktürk Empire in the 6th century. These were herdsmen and nobles who were searching for new pastures and wealth. The first mention of Turks was in a Chinese text that mentioned trade between Turk tribes and the Sogdians along the Silk Road.[64] The first recorded use of "Turk" as a political name appears as a 6th-century reference to the word pronounced in Modern Chinese as Tujue. The Ashina clan migrated from Li-jien (modern Zhelai Zhai) to the Juan Juan seeking inclusion in their confederacy and protection from the prevalent dynasty. The tribe were famed metalsmiths and were granted land near a mountain quarry which looked like a helmet, from which they were said to have gotten their name 突厥 (tūjué). A century later their power had increased such that they conquered the Juan Juan and established the Gök Empire.[65]

Turkic peoples originally used their own alphabets, like Orkhon and Yenisey runiforms, and later the Uyghur alphabet. Traditional national and cultural symbols of the Turkic peoples include wolves in Turkic mythology and tradition; as well as the color blue, iron, and fire. Turquoise blue (the word turquoise comes from the French word meaning "Turkish") is the color of the stone turquoise still used in jewelry and as a protection against evil eye.

It has often been suggested that the Xiongnu, mentioned in Han Dynasty records, were Proto-Turkic speakers.[66][67][68][69][70] Although little is known for certain about the Xiongnu language(s), it seems likely that at least a considerable part of Xiongnu tribes spoke a Turkic language.[71] However, some scholars see a possible connection with the Iranian-speaking Sakas.[72] Some scholars believe they were probably a confederation of various ethnic and linguistic groups.[73][74] Genetics research in 2003 on skeletons from 2000 year old Xiongnu necropolis in Mongolia found some individuals with DNA sequences also present in some modern-day Turks, suggesting that a Turkish component had emerged in the Xiongnu tribe at the end of the Xiongnu period.[75][76]

In 2009, archaeologists found Turkic balbals which are 2000 year old.[77][78]

According to another archeological and genetic study in 2010, the DNA found in three skeletons in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Asia belonged to C3, D4 and R1a. The evidence of paternal R1a supports the Kurgan hypothesis for the Indo-European expansion from the Volga steppe region.[79] As the R1a was found in Xiongnu people[79] and the present-day people of Central Asia[80] Analysis of skeletal remains from sites attributed to the Xiongnu provides an identification of dolichocephalic Mongoloid, ethnically distinct from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.[81]

Xiongnu writing, older than Turkic, is agreed to have the earliest known Turkic alphabet, the Orkhon script. This has been argued recently using the only extant possibly Xiongu writings, the rock art of the Yinshan and Helan Mountains.[82] It dates from the 9th millennium BCE to the 19th century, and consists mainly of engraved signs (petroglyphs) and few painted images.[83] Excavations done during 1924–1925 in Noin-Ula kurgans located in the Selenga River in the northern Mongolian hills north of Ulan Bator produced objects with over 20 carved characters, which were either identical or very similar to the runic letters of the Turkic Orkhon script discovered in the Orkhon Valley.[84]

The Hun hordes ruled by Attila, who invaded and conquered much of Europe in the 5th century, might have been Turkic and descendants of the Xiongnu.[62][85][86] Some scholars regard the Huns as one of the earlier Turkic tribes, while others view them as Proto-Mongolian in origin.[87] Linguistic studies by Otto Maenchen-Helfen and others have suggested that the language used by the Huns in Europe was too little documented to be classified, but may have been an Indo-European language. Nevertheless, many of the proper names used by Huns appear to be Turkic in origin.[88][89] In the first half of the first millennium, mass-migrations to distant places were common, geographical borders were fluid and cultural identity was more likely to change dramatically during the lifetime of an individual, relative to the modern era. These factors also made it more likely that the Huns were, initially at least, closely related to the Turkic peoples.

In the 6th century, 400 years after the collapse of northern Xiongnu power in Inner Asia, the Göktürks assumed leadership of the Turkic peoples. Formerly in the Xiongnu nomadic confederation, the Göktürks inherited their traditions and administrative experience. From 552 to 745, Göktürk leadership united the nomadic Turkic tribes into the Göktürk Empire on Mongolia and Cental Asia. The name derives from gok, "blue" or "celestial". Unlike its Xiongnu predecessor, the Göktürk Khanate had its temporary khans from the Ashina clan who were subordinate to a sovereign authority controlled by a council of tribal chiefs. The Khanate retained elements of its original shamanistic religion, Tengriism, although it received missionaries of Buddhist monks and practiced a syncretic religion. The Göktürks were the first Turkic people to write Old Turkic in a runic script, the Orkhon script. The Khanate was also the first state known as "Turk". It eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts, but many states and peoples later used the name "Turk".

Turkic peoples and related groups migrated west from Turkestan and present-day Mongolia towards Eastern Europe, the Iranian plateau and Anatolia (modern Turkey) in many waves. The date of the initial expansion remains unknown. After many battles, they established their own state and later constructed the Ottoman Empire. The main migration occurred in medieval times, when they spread across most of Asia and into Europe and the Middle East.[65] They also took part in the military encounters of the Crusades.[90]

Later Turkic peoples include the Pannonian Avars, Karluks (mainly 8th century), Uyghurs, Kyrgyz, Oghuz (or Ğuz) Turks, and Turkmens. As these peoples founded states in the area between Mongolia and Transoxiana, they came into contact with Muslims, and most of them gradually adopted Islam. Small groups of Turkic people practice other religions, including Christians, Jews (Khazars), Buddhists, and Zoroastrians.

Other traditions see Togarmah (grandson of Japheth the son of Noah) as the ancestor of the Turkic peoples. For example, The French Benedictine monk and scholar Calmet (1672–1757) places Togarmah in Scythia and Turcomania (in the Eurasian Steppes and Central Asia).[91] Also in his letters, King Joseph ben Aaron, the ruler of the Khazars in the mid-10th century, writes:

- "You ask us also in your epistle: "Of what people, of what family, and of what tribe are you?" Know that we are descended from Noach's son Japhet, through his son Gomer through his son Togarmah. I have found in the genealogical books of my ancestors that Togarmah had ten sons. These are their names:[25]

- the eldest was Ujur (Agiôr – Uyghurs),

- the second Tauris (Tirôsz – Tauri),

- the third Avar (Avôr – Pannonian Avars),

- the fourth Uauz (Ugin – Oghuz),

- the fifth Bizal (Bizel – Pecheneg),

- the sixth Tarna,

- the seventh Khazar (Khazar),

- the eighth Janur (Zagur),

- the ninth Bulgar (Balgôr – Bulgar),

- the tenth Sawir (Szavvir/Szabir – Sabir)."

Jewish sources also list Togarmah as the father of the Turkic peoples: The medieval Jewish scholar: Joseph ben Gorion lists in his Josippon (c. 10th century) the ten sons of Togarma as follows:

- Kozar (the Khazars)

- Pacinak (the Pechenegs)

- Aliqanosz (the Alans)

- Bulgar (the Bulgars)

- Ragbiga (Ragbina, Ranbona)

- Turqi (possibly the Göktürks)

- Buz (the Oghuz)

- Zabuk

- Ungari (either the Hungarians or the Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tilmac (Tilmic/Tirôsz – Tauri)."

The Chronicles of Jerahmeel lists them as:[92]

- Cuzar (the Khazars)

- Pasinaq (the Pechenegs)

- Alan (the Alans)

- Bulgar (the Bulgars)

- Kanbinah

- Turq (possibly the Göktürks)

- Buz (the Oghuz)

- Zakhukh

- Ugar (either the Hungarians or the Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tulmes (Tirôsz – Tauri)

Another medieval rabbinic work, the Book of Jasher, further corrupts[citation needed] these same names into:

- Buzar (the Khazars)

- Parzunac (the Pechenegs)

- Balgar (the Bulgars)

- Elicanum (the Alans)

- Ragbib

- Tarki (possibly the Göktürks)

- Bid (the Oghuz)

- Zebuc

- Ongal (Hungarians or Oghurs/Onogurs)

- Tilmaz (Tirôsz – Tauri).

Arabic records give Togorma's tribes as:[citation needed]

- Khazar (the Khazars)

- Badsanag (the Pechenegs)

- Asz-alân (the Alans)

- Bulghar (the Bulgars)

- Zabub

- Fitrakh (Kotrakh?) (Ko-etrakh. Etrakh means "Turks" [possibly Gokturks])

- Nabir

- Andsar (Ajhar)

- Talmisz (Tirôsz – Tauri)

- Adzîgher (Adzhigardak?).

The Arabic account however, also adds an 11th clan: Anszuh.

Yet another tradition of the sons of Togarmah appears in Pseudo-Philo, giving their names as "Abiud, Saphath, Asapli, and Zepthir". The Chronicles of Jerahmeel, in addition to giving Sefer haYashar (midrash) the above names from Yosippon, elsewhere lists Togarmah's sons similarly as "Abihud, Shafat, and Yaftir".

Middle Ages

Turkic soldiers in the army of the Abbasid caliphs emerged as the de facto rulers of most of the Muslim Middle East (apart from Syria and Egypt), particularly after the 10th century. The Oghuz and other tribes captured and dominated various countries under the leadership of the Seljuk dynasty and eventually captured the territories of the Abbasid dynasty and the Byzantine Empire.[65]

Meanwhile, the Yenisei Kyrgyz allied with China to destroy the Uyghur Khaganate in 840. The Kyrgyz people ultimately settled in the region now referred to as Kyrgyzstan. The Bulgars established themselves in between the Caspian and Black Seas in the 5th and 6th centuries, followed by their conquerors, the Khazars who converted to Judaism in the 8th or 9th century. After them came the Pechenegs who created a large confederacy, which was subsequently taken over by the Cumans and the Kipchaks. One group of Bulgars settled in the Volga region and mixed with local Volga Finns to become the Volga Bulgars in what is today Tatarstan. These Bulgars were conquered by the Mongols following their westward sweep under Genghis Khan in the 13th century. Other Bulgars settled in Southeastern Europe in the 7th and 8th centuries, and mixed with the Slavic population, adopting what eventually became the Slavic Bulgarian language. Everywhere, Turkic groups mixed with the local populations to varying degrees.[65] In 1090–91, the Turkic Pechenegs reached the walls of Constantinople, where Emperor Alexius I with the aid of the Kipchaks annihilated their army.[93]

Islamic empires

As the Seljuk Empire declined following the Mongol invasion, the Ottoman Empire emerged as the new important Turkic state, that came to dominate not only the Middle East, but even southeastern Europe, parts of southwestern Russia, and northern Africa.[65]

The Delhi Sultanate is a term used to cover five short-lived, Delhi-based kingdoms three of which were of Turkic origin in medieval India. These Turkic dynasties were the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90); the Khilji dynasty (1290–1320); and the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1414). Southern India, also saw many Turkic origin dynasties like Bahmani Sultanate, Adil Shahi dynasty, Bidar Sultanate, Qutb Shahi dynasty, collectively known as Deccan sultanates.

In Eastern Europe, Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 922 and influenced the region as it controlled many trade routes. In the 13th century, Mongols invaded Europe and established the Golden Horde in Eastern Europe, western & northern Central Asia, and even western Siberia. The Cuman-Kipchak Confederation and Islamic Volga Bulgaria were absorbed by the Golden Horde in the 13th century; in the 14th century, Islam became the official religion under Uzbeg Khan where the general population (Turks) as well as the aristocracy (Mongols) came to speak the Kipchak language and were collectively known as "Tatars" by Russians and Westerners. This country was also known as the Kipchak Khanate and covered most of what is today Ukraine, as well as the entirety of modern-day southern and eastern Russia (the European section). The Golden Horde disintegrated into several khanates and hordes in the 15th and 16th century including the Crimean Khanate, Khanate of Kazan, and Kazakh Khanate (among others), which were one by one conquered and annexed by the Russian Empire in the 16th through 19th centuries.

In Siberia, the Siberian Khanate was established in the 1490s by fleeing Tatar aristocrats of the disintegrating Golden Horde who established Islam as the official religion in western Siberia over the partly Islamized native Siberian Tatars and indigenous Uralic peoples. It was the northern-most Islamic state in recorded history and it survived up until 1598 when it was conquered by Russia.

The Chagatai Khanate was the eastern & southern Central Asian section of the Mongol Empire in what is today part or whole of Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Xinjiang ("Uyghurstan"). Like the Moghulistan and Golden Horde, the Chagatai Khanate became a Muslim state in the 14th century.

The Timurid Empire were an Turkic Uzbek-based empire founded in the late 14th century by Timurlane, a descendant of Genghis Khan. Timur, although a self-proclaimed devout Muslim, brought great slaughter in his conquest of fellow Muslims in neighboring Islamic territory and contributed to the ultimate demise of many Muslim states, including the Golden Horde.

The Mughal Empire was a Turkic-founded Indian empire that, at its greatest territorial extent, ruled most of the South Asia, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and parts of Uzbekistan from the early 16th to the early 18th centuries. The Mughal dynasty was founded by a Chagatai Turkic prince named Babur (reigned 1526–30), who was descended from the Turkic conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) on his father's side and from Chagatai, second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother's side.[94][95] A further distinction was the attempt of the Mughals to integrate Hindus and Muslims into a united Indian state.[94][96][97][98]

The Safavid dynasty of Persia,they were of mixed ancestry (Kurdish[99] and Azerbaijani,[100] which included intermarriages with Georgian,[101] Circassian,[102][103] and Pontic Greek[104] dignitaries). Through intermarriage and other political considerations, the Safavids spoke Persian and Turkish,[105][106] and some of the Shahs composed poems in their native Turkish language. Concurrently, the Shahs themselves also supported Persian literature, poetry and art projects including the grand Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp.[107][108] The Safavid dynasty ruled parts of Greater Iran for more than two centuries.[109][110][111][112] and established the Twelver school of Shi'a Islam[113] as the official religion of their empire, marking one of the most important turning points in Muslim history

The Afsharid dynasty was named after the Turkic Afshar tribe to which they belonged. The Afshars had migrated from Turkestan to Azerbaijan in the 13th century. The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the military commander Nader Shah who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself King of Iran. Nader belonged to the Qereqlu branch of the Afshars.[114] During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sassanid Empire.

Muslim Turks and non-Muslim Turks

The Muslim Kara-Khanid Turks performed Jihad against Buddhist Uyghur Turks during the Islamicisation and Turkicisation of Xinjiang.

The non-Muslim Turks worship of Tengri was mocked and insulted by the Muslim Turk Mahmud al-Kashgari, who wrote a verse referring to them – The Infidels – May God destroy them![115][116]

The Basmil, Yabāḳu and Uyghur states were among the Turkic peoples who fought against the Kara-Khanid's spread of Islam, the Islamic Kara-khanids were made out of Tukhai, Yaghma, Çiğil and Karluk.[117]

Kashgari claimed that the Prophet assisted in a miraculous event where 700,000 Yabāqu infidels were defeated by 40,000 Muslims led by Arslān Tegīn claiming that fires shot sparks from gates located on a green mountain towards the Yabāqu.[118] The Yabaqu were a Turkic people.[119]

The Muslim Kara-Khanid Turk Mahmud Kashgari insulted the Uyghur Buddhists as "Uighur dogs" and called them "Tats", which referred to the "Uighur infidels" according to the Tuxsi and Taghma, while other Turks called Persians "tat".[120][121] While Kashgari displayed a different attitude towards the Turks diviners beliefs and "national customs", he expressed towards Buddhism a hatred in his Diwan where he wrote the verse cycle on the war against Uighur Buddhists. Buddhist origin words like toyin (a cleric or priest) and Burxān or Furxan (meaning Buddha, acquiring the generic meaning of "idol" in the Turkic language of Kashgari) had negative connotations to Muslim Turks.[122][123]

Murals and statues of Medieval Turks

Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as phenotypically Mongoloid until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original, Caucasoid inhabitants, such as the Tocharians and eastern Iranian peoples.[124]

The Uyghurs of the Qocho and Turfan – whose ancestors had adopted the Buddhism of the Tocharians when they settled in the Tarim – were forcibly converted to Islam during a ghazat (holy war) by the Chagatai khan Khizr Khwaja.[125] After they had converted to Islam, subsequent generations of Uyghurs came to believe, falsely, that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) had built Buddhist monuments in the area.[126][127] The Buddhist murals at the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves were damaged by local Muslim population whose religion proscribed figurative images of sentient beings; the eyes and mouths in particular were often gouged out. Pieces of some murals were broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[128]

Turks in Arabic texts

The Arab Muslim Umayyads and Abbasids fought against the pagan Turks in the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana. The Muslims built ribats (military fortifications) against the non-Muslim Turks in Transoxiana.

The Medieval Arabs recorded that Medieval Turks looked strange from their perspective and were extremely physically different from the Arabs, calling them "broad faced people with small eyes".[129][130]

Medieval Muslim writers noted that Tibetans and Turks resembled each other and often were not able to tell the difference between Turks and Tibetans.[131]

The Hadith collection Sahih al-Bukhari records a Sahih Hadith by Muhammad on the Turks- Narrated Abu Huraira: Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) said, "The Hour will not be established until you fight with the Turks; people with small eyes, red faces, and flat noses. Their faces will look like shields coated with leather. The Hour will not be established till you fight with people whose shoes are made of hair." (حَدَّثَنَا سَعِيدُ بْنُ مُحَمَّدٍ، حَدَّثَنَا يَعْقُوبُ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبِي، عَنْ صَالِحٍ، عَنِ الأَعْرَجِ، قَالَ قَالَ أَبُو هُرَيْرَةَ ـ رضى الله عنه ـ قَالَ رَسُولُ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم " لاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى تُقَاتِلُوا التُّرْكَ صِغَارَ الأَعْيُنِ، حُمْرَ الْوُجُوهِ، ذُلْفَ الأُنُوفِ، كَأَنَّ وُجُوهَهُمُ الْمَجَانُّ الْمُطَرَّقَةُ، وَلاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى تُقَاتِلُوا قَوْمًا نِعَالُهُمُ الشَّعَرُ ".)[132][133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143][144]

Another Sahih al-Bukhari Hadith says – Narrated Abu Huraira: The Prophet (ﷺ) said, "The Hour will not be established till you fight a nation wearing hairy shoes, and till you fight the Turks, who will have small eyes, red faces and flat noses; and their faces will be like flat shields. And you will find that the best people are those who hate responsibility of ruling most of all till they are chosen to be the rulers. And the people are of different natures: The best in the pre-Islamic period are the best in Islam. A time will come when any of you will love to see me rather than to have his family and property doubled."(حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو الْيَمَانِ، أَخْبَرَنَا شُعَيْبٌ، حَدَّثَنَا أَبُو الزِّنَادِ، عَنِ الأَعْرَجِ، عَنْ أَبِي هُرَيْرَةَ ـ رضى الله عنه ـ عَنِ النَّبِيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَالَ " لاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى تُقَاتِلُوا قَوْمًا نِعَالُهُمُ الشَّعَرُ، وَحَتَّى تُقَاتِلُوا التُّرْكَ، صِغَارَ الأَعْيُنِ، حُمْرَ الْوُجُوهِ، ذُلْفَ الأُنُوفِ كَأَنَّ وُجُوهَهُمُ الْمَجَانُّ الْمُطْرَقَةُ ". "«وَتَجِدُونَ مِنْ خَيْرِ النَّاسِ أَشَدَّهُمْ كَرَاهِيَةً لِهَذَا الأَمْرِ، حَتَّى يَقَعَ فِيهِ، وَالنَّاسُ مَعَادِنُ، خِيَارُهُمْ فِي الْجَاهِلِيَّةِ خِيَارُهُمْ فِي الإِسْلاَمِ." "وَلَيَأْتِيَنَّ عَلَى أَحَدِكُمْ زَمَانٌ لأَنْ يَرَانِي أَحَبُّ إِلَيْهِ مِنْ أَنْ يَكُونَ لَهُ مِثْلُ أَهْلِهِ وَمَالِهِ.").[145]

A Sahih Hadith is also found in Sahih Muslim – Abu Huraira reported Allah's Messenger (ﷺ) as saying: The Last Hour would not come until the Muslims fight with the Turks-a people whose faces would be like hammered shields wearing clothes of hair and walking (with shoes) of hair. (حَدَّثَنَا قُتَيْبَةُ بْنُ سَعِيدٍ، حَدَّثَنَا يَعْقُوبُ، – يَعْنِي ابْنَ عَبْدِ الرَّحْمَنِ – عَنْ سُهَيْلٍ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ أَبِي هُرَيْرَةَ، أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَالَ " لاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى يُقَاتِلَ الْمُسْلِمُونَ التُّرْكَ قَوْمًا وُجُوهُهُمْ كَالْمَجَانِّ الْمُطْرَقَةِ يَلْبَسُونَ الشَّعَرَ وَيَمْشُونَ فِي الشَّعَرِ " .).[146]

A Sahih Hadith is also found in Sunan Nasai – It was narrated from Abu Hurairah that the Messenger of Allah (ﷺ) said: "The Hour will not begin until the Muslims fight the Turks, a people with faces like hammered shields who wear clothes made of hair and shoes made of hair." (أَخْبَرَنَا قُتَيْبَةُ، قَالَ حَدَّثَنَا يَعْقُوبُ، عَنْ سُهَيْلٍ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ أَبِي هُرَيْرَةَ، أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَالَ " لاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى يُقَاتِلَ الْمُسْلِمُونَ التُّرْكَ قَوْمًا وُجُوهُهُمْ كَالْمَجَانِّ الْمُطَرَّقَةِ يَلْبَسُونَ الشَّعَرَ وَيَمْشُونَ فِي الشَّعَرِ " .)[147]

A Sahih Hadith is also found in Abu Dawud- Abu Hurairah reported the Prophet (May peace be upon him) as saying: The last hour will not come before the Muslims fight with the Turks, a people whose faces look as if they were shields covered with skin, and who will wear sandals of hair. (حَدَّثَنَا قُتَيْبَةُ، حَدَّثَنَا يَعْقُوبُ، – يَعْنِي الإِسْكَنْدَرَانِيَّ – عَنْ سُهَيْلٍ، – يَعْنِي ابْنَ أَبِي صَالِحٍ – عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنْ أَبِي هُرَيْرَةَ، أَنَّ رَسُولَ اللَّهِ صلى الله عليه وسلم قَالَ " لاَ تَقُومُ السَّاعَةُ حَتَّى يُقَاتِلَ الْمُسْلِمُونَ التُّرْكَ قَوْمًا وُجُوهُهُمْ كَالْمَجَانِّ الْمُطْرَقَةِ يَلْبَسُونَ الشَّعْرَ " .)[148]

A Da'if Hadith is found in Abu Dawud – Buraidah said: In the tradition telling that people with small eyes, i.e. the Turks, will fight against you, the prophet (ﷺ) said: You will drive them off three times till you catch up with them in Arabia. On the first occasion when you drive them off those who fly will be safe, on the second occasion some will be safe and some will perish, but on the third occasion they will be extirpated, or he said words to that effect. (حَدَّثَنَا جَعْفَرُ بْنُ مُسَافِرٍ التِّنِّيسِيُّ، حَدَّثَنَا خَلاَّدُ بْنُ يَحْيَى، حَدَّثَنَا بَشِيرُ بْنُ الْمُهَاجِرِ، حَدَّثَنَا عَبْدُ اللَّهِ بْنُ بُرَيْدَةَ، عَنْ أَبِيهِ، عَنِ النَّبِيِّ صلى الله عليه وسلم فِي حَدِيثِ " يُقَاتِلُكُمْ قَوْمٌ صِغَارُ الأَعْيُنِ " . يَعْنِي التُّرْكَ قَالَ " تَسُوقُونَهُمْ ثَلاَثَ مِرَارٍ حَتَّى تُلْحِقُوهُمْ بِجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِ فَأَمَّا فِي السِّيَاقَةِ الأُولَى فَيَنْجُو مَنْ هَرَبَ مِنْهُمْ وَأَمَّا فِي الثَّانِيَةِ فَيَنْجُو بَعْضٌ وَيَهْلِكُ بَعْضٌ وَأَمَّا فِي الثَّالِثَةِ فَيُصْطَلَمُونَ " . أَوْ كَمَا قَالَ .).[149]

The Arab Muslims identified Banu Qantura' (بنو قنطوراء) as the Turks.[150][151][152] They were described as the Banu Qantura' people with wide faces and small eyes,[153] or a people with flat faces and small eyes[154] they have faces like shields covered with leather,[155][156][157]

A Hadith is found in Abu Dawud – Narrated AbuBakrah: The Apostle of Allah (peace_be_upon_him) said: Some of my people will alight on low-lying ground, which they will call al-Basrah, beside a river called Dajjal (the Tigris) over which there is a bridge. Its people will be numerous and it will be one of the capital cities of immigrants (or one of the capital cities of Muslims, according to the version of Ibn Yahya who reported from AbuMa'mar). At the end of time the descendants of Qantura' will come with broad faces and small eyes and alight on the bank of the river. The town's inhabitants will then separate into three sections, one of which will follow cattle and (live in) the desert and perish, another of which will seek security for themselves and perish, but a third will put their children behind their backs and fight the invaders, and they will be the martyrs.[158]

Turks in European accounts

The Turkomans observe a difference between their children from Turkoman mothers, and those from the Persian female captives whom they take as wives, and the Kazakh women whom they purchase from the Uzbeks of Khiva. The Turkomans of pure race enjoy full privileges, while the others are not allowed to contract marriages with Turkoman women of pure blood, but must choose themselves wives among the half-castes and Kazakh captives.

As there exists a great animosity between the Yamuds and Goklans they do not intermarry, although they reckon themselves of equally noble lineage. The same hatred is extended to the Tekke Turkomans, whom the Goklans and Yamuds, moreover, look upon as their inferiors, being, according to their genealogies, the descendants of a slave-woman, whilst they are the posterity of a free-woman. (p. 71)

The more intimate connection of the Astrakhan and Kazan Tartars with the Mogols can be traced in their features; with the Nogay it is less visible. In like manner, the Turkomans further off in the desert, and the Uzbeks of Khive, have more of the Mogol expression than the Turkomans who encamp near the Persian frontier. The frequent intercourse of the Nogay, in latter years, with the Cherkess, seems to have improved their race; and notwithstanding the enmity that exists between the Turkomans and the Persians, it is still not unlikely that their close vicinity should have produced on the former a similar effect in a lapse of several centuries. The fact we have seen, that the Turkomans marry Persian women, when they take them as prisoners. The Turkoman women are, like the men, tall, and when young, well-shaped; their faces are rounder than those of the men; the cheek-bones less prominent; the eyes black, with fine eye-brows, and many with fair complexion; the nose is rather flat; the mouth small, with a row of regular white teeth. In a word, a great number of the younger part of the community might be reckoned as fair specimens of pretty women. (p. 73)

Bode, C.A. "The Yamud and Goklan tribes of Turkomania". Journal of the London Ethnological Society, vol. 1, 1848, pp. 60–78.

Modern history

The Ottoman Empire gradually grew weaker in the face of poor administration, repeated wars with Russia and Austro-Hungary, and the emergence of nationalist movements in the Balkans, and it finally gave way after World War I to the present-day Republic of Turkey.[65] Ethnic nationalism also developed in Ottoman Empire during the 19th century, taking the form of Pan-Turkism or Turanism.

The Turkic peoples of Central Asia were not organized in nation-states during most of the 20th century, after the collapse of the Russian Empire living either in the Soviet Union or (after a short-lived First East Turkestan Republic) in the Chinese Republic.

In 1991, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, five Turkic states gained their independence. These were Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Other Turkic regions such as Tatarstan, Tuva, and Yakutia remained in the Russian Federation. Chinese Turkestan remained part of the People's Republic of China.

Immediately after the independence of the Turkic states, Turkey began seeking diplomatic relations with them. Over time political meetings between the Turkic countries increased and led to the establishment of TÜRKSOY in 1993 and later the Turkic Council in 2009.

Geographical distribution

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2010) |

Many of the Turkic peoples have their homelands in Central Asia, where the Turkic peoples settled from China. According to historian John Foster, "The Turks emerge from among the Huns in the middle of [the] fifth century. They were living in Liang territory when it began to be overrun by the greater principality of Wei. Preferring to remain under the rule of their own kind, they moved westward into what is now the province of Kansu. This was the territory of kindred Huns, who were called the Rouran. The Turks were a small tribe of only five hundred families, and they became serfs to the Rouran, who used them as iron-workers. It is thought that the original meaning of "Turk" is "helmet", and that they may have taken this name because of the shape of one of the hills near which they worked. As their numbers and power grew, their chief made bold to ask for the hand of a Rouran princess in marriage. The demand was refused, and war followed. In 546, the iron-workers defeated their overlords."[159] Since then Turkic languages have spread, through migrations and conquests, to other locations including present-day Turkey. While the term "Turk" may refer to a member of any Turkic people, the term Turkish usually refers specifically to the people and language of the modern country of Turkey.

The Turkic languages constitute a language family of some 30 languages, spoken across a vast area from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, to Siberia and Western China, and through to the Middle East.

Some 170 million people have a Turkic language as their native language;[160] an additional 20 million people speak a Turkic language as a second language. The Turkic language with the greatest number of speakers is Turkish proper, or Anatolian Turkish, the speakers of which account for about 40% of all Turkic speakers.[161] More than one third of these are ethnic Turks of Turkey, dwelling predominantly in Turkey proper and formerly Ottoman-dominated areas of Eastern Europe and West Asia; as well as in Western Europe, Australia and the Americas as a result of immigration. The remainder of the Turkic people are concentrated in Central Asia, Russia, the Caucasus, China, and northern Iraq.

At present, there are six independent Turkic countries: Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Turkey, Uzbekistan; There are also several Turkic national subdivisions[162] in the Russian Federation including Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, Chuvashia, Khakassia, Tuva, Yakutia, the Altai Republic, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Karachayevo-Cherkessiya. Each of these subdivisions has its own flag, parliament, laws, and official state language (in addition to Russian).

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in western China and the autonomous region of Gagauzia, located within eastern Moldova and bordering Ukraine to the north, are two major autonomous Turkic regions. The Autonomous Republic of Crimea within Ukraine is a home of Crimean Tatars. In addition, there are several Iraq, Georgia, Bulgaria, the Republic of Macedonia, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, and western Mongolia.

The Turks in Turkey are over 60 million[163] to 70 million worldwide, while the second largest Turkic people are the Azerbaijanis, numbering 22 to 38 million worldwide; most of them live in Azerbaijan and Iran.

Turks in India are very small in number. There are barely 150 Turkish people from Turkey in India. These are recent immigrants. Descendants of Turkish rulers also exist in Northern India. Mughals who are part Turkic people also live in India in significant numbers. They are descendants of the Mughal rulers of India. Karlugh Turks are also found in the Haraza region and in smaller number in Azad Kashmir region of Pakistan. Small amount of Uyghurs are also present in India. Turks also exist in Pakistan in similar proportions. One of the tribe in Hazara region of Pakistan is Karlugh Turks which is direct descendant of Turks of Central Asia. Turkish influence in Pakistan can be seen through the national language, Urdu, which comes from a Turkish word meaning "horde" or "army".

The Western Yugur at Gansu in China, Salar at Qinghai in China, the Dolgan at Krasnoyarsk Krai in Russia, and the Nogai at Dagestan in Russia are the Turk minorities in the respective regions.

International organizations

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (December 2009) |

There are several international organizations created with the purpose of furthering cooperation between countries with Turkic-speaking populations, such as the Joint Administration of Turkic Arts and Culture (TÜRKSOY) and the Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-speaking Countries (TÜRKPA).

The newly established Turkic Council, founded on November 3, 2009 by the Nakhchivan Agreement Mongolian confederation, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Turkey, aims to integrate these organizations into a tighter geopolitical framework.

The TAKM – Organization of the Eurasian Law Enforcement Agencies with Military Status, established on 25 January 2013.

Demographics

The distribution of people of Turkic cultural background ranges from Siberia, across Central Asia, to Eastern Europe. As of 2011[update] the largest groups of Turkic people live throughout Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan, in addition to Turkey and Iran. Additionally, Turkic people are found within Crimea, Altishahr region of western China, northern Iraq, Israel, Russia, Afghanistan, and the Balkans: Moldova, Bulgaria, Romania, and former Yugoslavia. A small number of Turkic people also live in Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. Small numbers inhabit eastern Poland and the south-eastern part of Finland.[164] There are also considerable populations of Turkic people (originating mostly from Turkey) in Germany, United States, and Australia, largely because of migrations during the 20th century.

Sometimes ethnographers group Turkic people into six branches: the Oghuz Turks, Kipchak, Karluk, Siberian, Chuvash, and Sakha/Yakut branches. The Oghuz have been termed Western Turks, while the remaining five, in such a classificatory scheme, are called Eastern Turks.

All the Turkic peoples native to Central Asia are of mixed Caucasoid and Mongoloid origin. The genetic distances between the different populations of Uzbeks scattered across Uzbekistan is no greater than the distance between many of them and the Karakalpaks. This suggests that Karakalpaks and Uzbeks have very similar origins. The Karakalpaks have a somewhat greater bias towards the eastern markers than the Uzbeks.[165]

Historical population:

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1 AD | 2–2.5 million? |

| 2013 | 150–200 million |

The Turkic people display a great variety of ethnic types.[166] They possess physical features ranging from Caucasoid to Northern Mongoloid. Mongoloid and Caucasoid facial structure is common among many Turkic groups, such as Chuvash people, Tatars, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, and Bashkirs.

The following incomplete list of Turkic people shows the respective groups' core areas of settlement and their estimated sizes (in millions):

| People | Primary homeland | Population | Modern language | Predominant religion and sect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turks | Turkey | 70 M | Turkish | Sunni Islam |

| Azerbaijanis | Iranian Azerbaijan, Republic of Azerbaijan | 35 M | Azerbaijani | Shia Islam |

| Uzbeks | Uzbekistan | 28.3 M | Uzbek | Sunni Islam |

| Kazakhs | Kazakhstan | 13.8 M | Kazakh | Sunni Islam |

| Uyghurs | Altishahr (China) | 9 M | Uyghur | Sunni Islam |

| Turkmens | Turkmenistan | 8 M | Turkmen | Sunni Islam |

| Tatars | Tatarstan | 7 M | Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Kyrgyzs | Kyrgyzstan | 4.5 M | Kyrgyz | Sunni Islam |

| Bashkirs | Bashkortostan (Russia) | 2 M | Bashkir | Sunni Islam |

| Crimean Tatars | Crimea (Russia/Ukraine) | 0.5 to 2 M | Crimean Tatar | Sunni Islam |

| Qashqai | Southern Iran | 1.7 M | Qashqai | Shia Islam |

| Chuvashes | Chuvashia | 1.7 M | Chuvash | Orthodox Christianity |

| Karakalpaks | Karakalpakstan (Uzbekistan) | 0.6 M | Karakalpak | Sunni Islam |

| Yakuts | Yakutia (Russia) | 0.5 M | Sakha | Orthodox Christianity |

| Kumyks | Dagestan (Russia) | 0.4 M | Kumyk | Sunni Islam |

| Karachays and Balkars | Karachay-Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria (Russia) | 0.4 M | Karachay-Balkar | Sunni Islam |

| Tuvans | Tuva (Russia) | 0.3 M | Tuvan | Tibetan Buddhism |

| Gagauzs | Gagauzia (Moldova) | 0.2 M | Gagauz | Orthodox Christianity |

| Turkic Karaites and Krymchaks | Ukraine | 0.2 M | Karaim and Krymchak | Judaism |

Language

The Turkic alphabets are sets of related alphabets with letters (formerly known as runes), used for writing mostly Turkic languages. Inscriptions in Turkic alphabets were found from Mongolia and Eastern Turkestan in the east to Balkans in the west. Most of the preserved inscriptions were dated to between 8th and 10th centuries CE.

The earliest positively dated and read Turkic inscriptions date from c. 150, and the alphabets were generally replaced by the Uyghur alphabet in the Central Asia, Arabic script in the Middle and Western Asia, Greek-derived Cyrillic in Eastern Europe and in the Balkans, and Latin alphabet in Central Europe. The latest recorded use of Turkic alphabet was recorded in Central Europe's Hungary in 1699 CE.

The Turkic runiform scripts, unlike other typologically close scripts of the world, do not have a uniform palaeography as, for example, have the Gothic runes, noted for the exceptional uniformity of its language and paleography.[167] The Turkic alphabets are divided into four groups, the best known of them is the Orkhon version of the Enisei group. The Orkhon script is the alphabet used by the Göktürks from the 8th century to record the Old Turkic language. It was later used by the Uyghur Empire; a Yenisei variant is known from 9th-century Kyrgyz inscriptions, and it has likely cousins in the Talas Valley of Turkestan and the Old Hungarian script of the 10th century.

The Turkic language family is traditionally considered to be part of the proposed Altaic language family.[161][168][169][170]

The various Turkic languages are usually considered in geographical groupings: the Oghuz (or Southwestern) languages, the Kypchak (or Northwestern) languages, the Eastern languages (like Uygur), the Northern languages (like Altay and Yakut), and one existing Oghur language: Chuvash (the other Oghur languages, like Hunnic and Bulgaric, are now extinct). The high mobility and intermixing of Turkic peoples in history makes an exact classification extremely difficult.

The Turkish language belongs to the Oghuz subfamily of Turkic. It is for the most part mutually intelligible with the other Oghuz languages, which include Azerbaijani, Gagauz, Turkmen and Urum, and to a varying extent with the other Turkic languages.

Religion

Early Turkic mythology and shamanism

Pre-Islamic Turkic mythology was dominated by shamanism. The chief deity was Tengri, a sky god, worshipped by the upper classes of early Turkic society until Manichaeism was introduced as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire in 763. The wolf symbolizes honour and is also considered the mother of most Turkic peoples. Asena (Ashina Tuwu) is the wolf mother of Tumen Il-Qağan, the first Khan of the Göktürks. The horse is also one of the main figures of Turkic mythology.

Religious conversions

Tengri Bögü Khan made the now extinct Manichaeism the state religion of Uyghur Khaganate in 763 and it was also popular in Karluks. It was gradually replaced by the Mahayana Buddhism.[citation needed] It existed in the Buddhist Uyghur Gaochang up to the 12th century.[171]

Tibetan Buddhism, or Vajrayana was the main religion after Manichaeism.[172] They worshipped Täŋri Täŋrisi Burxan,[173] Quanšï Im Pusar[174] and Maitri Burxan.[175] Turkic Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent and west Xinjiang attributed with a rapid and almost total disappearance of it and other religions in North India and Central Asia. The Sari Uygurs "Yellow Yughurs" of Western China, as well as the Tuvans of Russia are the only remaining Buddhist Turkic peoples.

The Krymchaks of Eastern Europe (Especially Crimea) are Jewish, and there are Turks of Jewish backgrounds who live in major cities such as Istanbul, Ankara and Baku. The Khazars widely practiced Judaism before their conversion to Islam.[citation needed]

Even though many Turkic peoples became Muslims under the influence of Sufis, often of Shī‘ah persuasion, most Turkic people today are Sunni Muslims, although a significant number in Turkey are Alevis. Alevi Turks, who were once primarily dwelling in eastern Anatolia, are today concentrated in major urban centers in western Turkey with the increased urbanism.

The major Christian-Turkic peoples are the Chuvash of Chuvashia and the Gagauz (Gökoğuz) of Moldova. The traditional religion of the Chuvash of Russia, while containing many ancient Turkic concepts, also shares some elements with Zoroastrianism, Khazar Judaism, and Islam. The Chuvash converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity for the most part in the second half of the 19th century. As a result, festivals and rites were made to coincide with Orthodox feasts, and Christian rites replaced their traditional counterparts. A minority of the Chuvash still profess their traditional faith.[176] Church of the East was popular among Turks such as the Naimans.[177] It even revived in Gaochang and expanded in Xinjiang in the Yuan dynasty period.[178][179][180] It disappeared after its collapse.[181][182]

Old sports

The Kyz kuu (chase the girl) – it has been played by Turkic people at festivals since time immemorial.[183]

The Jereed – Horses have been essential and even sacred animals for Turks living as nomadic tribes in the Central Asian steppes. Turks were born, grew up, lived, fought and died on horseback. So became jereed the most important sporting and ceremonial game of Turkish people.[184]

The kokpar began with the nomadic Turkic peoples who have come from farther north and east spreading westward from China and Mongolia between the 10th and 15th centuries.[185]

The jigit which is used in the Caucasus and Central Asia to describe a skillful and brave equestrian, or a brave person in general.[186]

Gallery

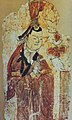

Images of Mongoloid Buddhist and Manichean Turkic Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes

-

Uyghur king from Turfan, from the murals at the Dunhuang Mogao Caves.

-

Uyghur prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur woman from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Princess.

-

Uyghur Princesses from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Princes from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Prince from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur noble from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur donor from the Bezeklik murals.

-

Uyghur Manichaean Electae from Qocho.

-

Uyghur Manichaean clergymen from Qocho.

-

Art from Qocho.

-

Manicheans from Qocho

Medieval times

Modern times

-

Azerbaijani girls in traditional dress.

-

Young and old Gagauz people.

-

Turkmen girl in national dress.

-

Turkish women playing backgammon.

-

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton visits Tatarstan.

-

Bashkir boys in national dress.

-

A Chuvash woman in traditional dress.

-

Uyghur man of Yarkand.

-

Two Uyghur elders from Turpan.

-

A female Chuvash dancer in traditional dress.

-

Tatar woman in the 18th century.

-

Female Azerbaijani from Baku.

-

Karachay patriarchs in the 19th century

-

Uyghur farmer, Xinjiang.

-

Altay man in national suit on horse

-

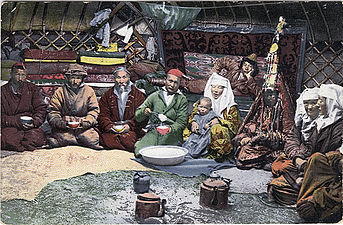

Kazakh family inside a Yurt

See also

- Bulaks

- Por-Bazhyn

- Ordu-Baliq

- Jankent

- Chigils Turks

- Shato

- Pan-Turanism

- Pan-Turkism

- Turkic languages

- Turkic migrations

- Turkic states and empires

- Turko-Iranian

- Turko-Persian tradition

- Turko-Mongol

- Turkology

- List of ethnic groups

- List of Turkic dynasties and countries

- European ethnic groups

- Peoples of the Caucasus

References

- ^ Brigitte Moser, Michael Wilhelm Weithmann, Landeskunde Türkei: Geschichte, Gesellschaft und Kultur, Buske Publishing, 2008, p. 173

- ^ Deutsches Orient-Institut, Orient, Vol. 41, Alfred Röper Publushing, 2000, p. 611

- ^ "Turkey". The World Factbook. Retrieved 21 December 2014. "Population: 81,619,392 (July 2014 est.)" "Ethnic groups: Turkish 70–75%, Kurdish 18%, other minorities 7–12% (2008 est.)" 70% of 81.6m = 57.1m, 75% of 81.6m = 61.2m

- ^ "Uzbekistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 21 December 2014. "Population: 28,929,716 (July 2014 est.)" "Ethnic groups: Uzbek 80%, Russian 5.5%, Tajik 5%, Kazakh 3%, Karakalpak 2.5%, Tatar 1.5%, other 2.5% (1996 est.)" Assuming Uzbek, Kazakh, Karakalpak and Tartar are included as Turks, 80% + 3% + 2.5% + 1.5% = 87%. 87% of 28.9m = 25.2m

- ^ "Azerbaijani (people)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Kazakhstan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 21 December 2014. "Population: 17,948,816 (July 2014 est.)" "Ethnic groups: Kazakh (Qazaq) 63.1%, Russian 23.7%, Uzbek 2.9%, Ukrainian 2.1%, Uighur 1.4%, Tatar 1.3%, German 1.1%, other 4.4% (2009 est.)" Assuming Kazakh, Uzbek, Uighur and Tatar are included as Turks, 63.1% + 2.9% + 1.4% + 1.3% = 68.7%. 68.7% of 17.9m = 12.3m

- ^ ru:Этно-языковой состав населения России

- ^ "China". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Azerbaijan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 30 July 2016. "Population: 9,780,780 (July 2015 est.)"

- ^ "Turkmenistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Afghanistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Iraq". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Tajikistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Obama, recognize us". St. Louis American. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Nahost-Informationsdienst (ISSN 0949-1856): Presseausschnitte zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft in Nordafrika und dem Nahen und Mittleren Osten. Autors: Deutsches Orient–Institut; Deutsches Übersee–Institut. Hamburg: Deutsches Orient–Institut, 1996, seite 33.

The number of Turkmens in Syria is not fully known, with unconfirmed estimates ranging between 800,000 and one million.

- ^ "Pakistan". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Census.XLS" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-02-14.

- ^ "Georgia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Results / General results of the census / National composition of population". All-Ukrainian Census, 2001. December 5, 2001. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ "Moldova". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Mongolia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Macedonia". The World Factbook. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ a b Turkic people, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Academic Edition, 2010

- ^ a b Pritsak O. & Golb. N: Khazarian Hebrew Documents of the Tenth Century, Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 1982.

- ^ "Timur", The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition, 2001–05, Columbia University Press.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica article: Consolidation & expansion of the Indo-Timurids, Online Edition, 2007.

- ^ Walton, ,Linda (2013). World History: Journeys from Past to Present. p. 210.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ a b Kultegin's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments

- ^ a b Bilge Kagan's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments

- ^ Tonyukuk's Memorial Complex, TÜRIK BITIG Bain Tsokto Monument

- ^ Tarihte Türk devletleri, Volume 1. Ankara Üniversitesi Basımevi, 1987. p. 1.

- ^ Moše Weinfeld. Social Justice in Ancient Israel and in the Ancient Near East. 1995. p. 66: "For the concept of durgu | duruggu and its connection to piY (in its meaning "origin"), see H. Tadmor, (above n. 25), p. 28"

- ^ "新亞研究所 – 典籍資料庫". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ The Turkmen

- ^ Pliny, Natural History – Harvard University Press, vol. II (Libri III-VII); reprinted 1961, p. 351

- ^ Pomponius Mela's Description of the World,Pomponius Mela, University of Michigan Press, 1998, p. 67

- ^ Sevan Nişanyan, Çağdaş Türkçenin Etimolojik Sözlüğü, İstanbul, 2009 ISBN 9789752896369

- ^ Abdulkadir İnan, Urartu yazıtında ve Romalı Plinius'un tarihinde «Türk Adı» var mı? Belleten, TTK, Cilt. XlI, p. 45, 1948, pp. 277–278

- ^ dile Ayda, Une Theorle Sur L'Orlglne Du Mot «Türk», «Türk» kelimesinin Menşei Hakkında Bir Nazariye, TTK, Belleten. Cilt. XL., No. 158, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Nisan 1976, s. 229 – 247

- ^ Hamit Koşay, ldil – Ural bölgesindeki Türkler'In Menşei Hakkında, V. Türk Tarih Kongresi: 12–17 Nisan 1956, TTK. Basımevi. Ankara 1960. s. 232–243

- ^ Laszlo Rasonyi, Dünya'da Türklük, Türk Kültürünü Araştırma Enstitüsü Yayınları. Ayyıldız Matbaası, Ankara 1974

- ^ Prof. Dr. Ercümend Kuran, Türk Adı ve Türklük Kavramı, Türk Kültürü Dergisi, Yıl, XV, S. 174, Nisan 1977. s. 18–20.

- ^ Boris Altschüler. Die Aschkenasim: Letzte Skythen, erste Europäer – von den zehn verschollenen Stämmen Israels zu den Awaren und Khasaren / Boris Altschüler, Volume 1. 2006. p. 192: "Das Ethnonym "Turk" wird mit dem von Herodot überlieferten Namen des ersten skythischen Königs [Targitaos] oder auch mit dem Namen des Ahnherrn "Togarma" aus dem Alten Testament, mit "Turukha/Turuska" aus indischen Quellen und "Turukku" aus assyrischen Dokumenten und anderen schriftlichen Denkmälern in Verbindung gebracht." (P. Golden)

- ^ Peter B. Golden, Introduction to the History of the Turkic People, p. 12: "... source (Herod.IV.22) and other authors of antiquity, Togarma of the Old Testament, Turukha/Turuska of Indic sources, Turukku of Assyrian..."

- ^ German Archaeological Institute. Department Teheran, Archaeologische Mitteilungen aus Iran, Vol. 19, Dietrich Reimer, 1986, p. 90

- ^ András Róna-Tas, Hungarians and Europe in the early Middle Ages: an introduction to early Hungarian history, Central European University Press, 1999, p. 281: "We can now reconstruct the history of the ethnic name Turk as follows. The word is of East Iranian, most probably Saka, origin, and is the name of a ruling tribe whose leading clan Ashina conquered the Turks, reorganized them, but itself became rapidly Turkified."

- ^ Golden, Peter B. "Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Turks and the Shaping of the Turkic Peoples". (2006) In: Contact and Exchange in the Ancient World. Ed. Victor H. Mair. University of Hawai'i Press. p. 143: "Subsequently, "Tùrk" would find a suirable Turkic etymology, being conflated with the word tùrk, which means one in the prime of youth, powerful, mighty (Rona-Tas 1991,10–13)."

- ^ (Bŭlgarska akademii︠a︡ na naukite. Otdelenie za ezikoznanie/ izkustvoznanie/ literatura, Linguistique balkanique, Vol. 27–28, 1984, p. 17

- ^ a b c “Türk” in Turkish Etymological Dictionary, Sevan Nişanyan.

- ^ Murat Ocak, The Turks: Early ages, Yeni Türkiye, 2002

- ^ Faruk Suümer, Oghuzes (Turkmens): History, Tribal organization, Sagas, Turkish World Research Foundation, 1992, p. 16)

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary (2000). "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition – "Turk"". bartleby.com. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ “türe-” in Turkish Etymological Dictionary, Sevan Nişanyan.

- ^ “*töŕ” in Sergei Starostin, Vladimir Dybo, Oleg Mudrak (2003), Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

- ^ “*t`ŏ̀ŕe” in Sergei Starostin, Vladimir Dybo, Oleg Mudrak (2003), Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages, Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

- ^ THE PEOPLES OF THE STEPPE FRONTIER IN EARLY CHINESE SOURCES, Edwin G. Pulleyblank, page 35

- ^ Studies on the Peoples and Cultures of the Eurasian Steppes, PETER B. GOLDEN, page 27, http://www.academia.edu/9609971/Studies_on_the_Peoples_and_Cultures_of_the_Eurasian_Steppes

- ^ a b G. Moravcsik, Byzantinoturcica II, p. 236–39

- ^ Jean-Paul Roux, Historie des Turks – Deux mille ans du Pacifique á la Méditerranée. Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2000.

- ^ a b Peter Zieme: The Old Turkish Empires in Mongolia. In: Genghis Khan and his heirs. The Empire of the Mongols. Special tape for Exhibition 2005/2006, p. 64

- ^ a b Findley (2005), p. 29.

- ^ "丁零—铁勒的西迁及其所建西域政权". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Etienne de la Vaissiere", Encyclopædia Iranica article:Sogdian Trade, 1 December 2004.

- ^ a b c d e f Carter V. Findley, The Turks in World History (Oxford University Press, October 2004) ISBN 0-19-517726-6

- ^ Silk-Road:Xiongnu

- ^ "Yeni Turkiye Research and Publishing Center". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "An Introduction to the Turkic Tribes". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Early Turkish History at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- ^ "An outline of Turkish History until 1923". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Lebedynsky (2006), p. 59.

- ^ Beckwith (2009), pp. 72–73 and 404–405, nn. 51–52.

- ^ Nicola di Cosmo, Ancient China and its Enemies, S. 163ff.

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- ^ "Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA analysis of a 2,000-year-old necropolis in the Egyin Gol Valley of Mongolia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 73 (2): 247–260. 2003. doi:10.1086/377005. PMC 1180365. PMID 12858290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Nancy Touchette Ancient DNA Tells Tales from the Grave "Skeletons from the most recent graves also contained DNA sequences similar to those in people from present-day Turkey. This supports other studies indicating that Turkic tribes originated at least in part in Mongolia at the end of the Xiongnu period."

- ^ TIKA. "TIKA supports archaeological digs in Kazakhstan".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Fethi Ahmet Yüksel. "Kazakistan Kumay Vadisi Kumay Türk Arkeoloji-Etnografya Kompleksi 2013 Yılı Arkeojeofizik Çalışmaları".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Kim, Kijeong; Brenner, Charles H.; Mair, Victor H.; Lee, Kwang-Ho; Kim, Jae-Hyun; Gelegdorj, Eregzen; Batbold, Natsag; Song, Yi-Chung; Yun, Hyeung-Won; Chang, Eun-Jeong; Lkhagvasuren, Gavaachimed; Bazarragchaa, Munkhtsetseg; Park, Ae-Ja; Lim, Inja; Hong, Yun-Pyo; Kim, Wonyong; Chung, Sang-In; Kim, Dae-Jin; Chung, Yoon-Hee; Kim, Sung-Su; Lee, Won-Bok; Kim, Kyung-Yong (2010). "A western Eurasian male is found in 2000-year-old elite Xiongnu cemetery in Northeast Mongolia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 142 (3): 429–40. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21242. PMID 20091844.

- ^ Xue, Y.; Zerjal, T; Bao, W; Zhu, S; Shu, Q; Xu, J; Du, R; Fu, S; Li, P; Hurles, M. E.; Yang, H; Tyler-Smith, C (2005). "Male Demography in East Asia: A North-South Contrast in Human Population Expansion Times". Genetics. 172 (4): 2431–9. doi:10.1534/genetics.105.054270. PMC 1456369. PMID 16489223.

- ^ Psarras, Sophia-Karin (2003). "Han and Xiongnu: A Reexamination of Cultural and Political Relations (I)". Monumenta Serica. 51: 55–236. JSTOR 40727370.

- ^ MA Li-qing On the new evidence on Xiongnu's writings. (Wanfang Data: Digital Periodicals, 2004)

- ^ Paola Demattè Writing the Landscape: the Petroglyphs of Inner Mongolia and Ningxia Province (China). (Paper presented at the First International Conference of Eurasian Archaeology, University of Chicago, 3–4 May 2002.)

- ^ N. Ishjatms, "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, Fig 6, p. 166, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4

- ^ Ulrich Theobald. "Chinese History – Xiongnu 匈奴 (www.chinaknowledge.de)". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ G. Pulleyblank, "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese: Part II", Asia Major n.s. 9 (1963) 206–65

- ^ "The Origins of the Huns". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Otto J. Maenchen-Helfen. The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University of California Press, 1973

- ^ "Otto Maenchen-Helfen, Language of Huns". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Moses Parkson, "Ottoman Empire and its past life" p. 98

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. (1835) B. B. Edwards and J. Newton Brown. Brattleboro, Vermont, Fessenden & Co., p. 1125.

- ^ The Chronicles of Jeraḥmeel. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ The Pechenegs at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009), Steven Lowe and Dmitriy V. Ryaboy

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica Article:Mughal Dynasty

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Article:Babur

- ^ "the Mughal dynasty". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "Kamat's Potpourri". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Babur: Encyclopædia Britannica Article

- ^ RM Savory. Ebn Bazzaz. Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ "Peoples of Iran" Encyclopædia Iranica. RN Frye.

- ^ Aptin Khanbaghi (2006) The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early. London & New York. IB Tauris. ISBN 1-84511-056-0, pp. 130-1

- ^ Yarshater 2001, p. 493.

- ^ Khanbaghi 2006, p. 130.

- ^ Anthony Bryer. "Greeks and Türkmens: The Pontic Exception", Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 29 (1975), Appendix II "Genealogy of the Muslim Marriages of the Princesses of Trebizond"

- ^ Savory, Roger (2007). Iran Under the Safavids. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-521-04251-2.

qizilbash normally spoke Azari brand of Turkish at court, as did the Safavid shahs themselves; lack of familiarity with the Persian language may have contributed to the decline from the pure classical standards of former times

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ E. Yarshater, "Iran", . Encyclopædia Iranica. "The origins of the Safavids are clouded in obscurity. They may have been of Kurdish origin (see R. Savory, Iran Under the Safavids, 1980, p. 2; R. Matthee, "Safavid Dynasty" at iranica.com), but for all practical purposes they were Turkish-speaking and Turkified. "

- ^ John L. Esposito, The Oxford History of Islam, Oxford University Press US, 1999. pp 364: "To support their legitimacy, the Safavid dynasty of Iran (1501–1732) devoted a cultural policy to establish their regime as the reconstruction of the historic Iranian monarchy. To the end, they commissioned elaborate copies of the Shahnameh, the Iranian national epic, such as this one made for Tahmasp in the 1520s."

- ^ Ira Marvin Lapidus, A history of Islamic Societies, Cambridge University Press, 2002, 2nd edition. pg 445: To bolster the prestige of the state, the Safavid dynasty sponsored an Iran-Islamic style of culture concentrating on court poetry, painting, and monumental architecture that symbolized not only the Islamic credentials of the state but also the glory of the ancient Persian traditions."

- ^ Helen Chapin Metz. Iran, a Country study. 1989. University of Michigan, p. 313.

- ^ Emory C. Bogle. Islam: Origin and Belief. University of Texas Press. 1989, p. 145.

- ^ Stanford Jay Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire. Cambridge University Press. 1977, p. 77.

- ^ Andrew J. Newman, Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire, IB Tauris (March 30, 2006).

- ^ RM Savory, Safavids, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd ed.

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran Volume 7, pp. 2–4

- ^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 95 (1). American Oriental Society: 70. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 689.

- ^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ^ Mehmet Fuat Köprülü; Gary Leiser; Robert Dankoff (2006). Early Mystics in Turkish Literature. Psychology Press. pp. 147–. ISBN 978-0-415-36686-1.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20151118063834/http://projects.iq.harvard.edu/huri/files/viii-iv_1979-1980_part1.pdf p. 160.

- ^ Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute (1980). Harvard Ukrainian studies. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute. p. 160.

- ^ Robert Dankoff (2008). From Mahmud Kaşgari to Evliya Çelebi. Isis Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-975-428-366-2.

- ^ Dankoff, Robert (Jan–Mar 1975). "Kāšġarī on the Beliefs and Superstitions of the Turks". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 95 (1). American Oriental Society: 69. doi:10.2307/599159. JSTOR 599159.

- ^ Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0231139241. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ^ Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen Gibb; Bernard Lewis; Johannes Hendrik Kramers; Charles Pellat; Joseph Schacht (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill. p. 677.

- ^ [1][2][3]

- ^ Whitfield, Susan (2010). "A place of safekeeping? The vicissitudes of the Bezeklik murals". In Agnew, Neville (ed.). History and Silk Road Studies Conservation of ancient sites on the Silk Road: proceedings of the second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China. Getty Publications. pp. 95–106. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ The Turks of the Eurasian Steppes in Medieval Arabic Writing, R. Amitai, M. Biran, eds., Mongols, Turks and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World. Leyde, Brill, 2005, pp. 222–3.

- ^ Reuven Amitai; Michal Biran (2005). Mongols, Turks, and Others: Eurasian Nomads and the Sedentary World. Brill. p. 222. ISBN 978-90-04-14096-7.

- ^ André Wink (2002). Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th–13th centuries. BRILL. pp. 69–. ISBN 0-391-04174-6.

- ^ : Sahih al-Bukhari 2928 : Book 56, Hadith 141 : Vol. 4, Book 52, Hadith 179

- ^ Hadith 4:179

- ^ IslamKotob. bukharitext. IslamKotob. pp. 689–. GGKEY:FBLX1RRQSHD.

- ^ Bill McLean; IslamKotob. bukhari. IslamKotob. pp. 689–. GGKEY:TAALKTXZJCJ.

- ^ Muhammad Muhsin Khan (1971). Sahih Bukhari. Peace Vision. pp. 684–. ISBN 978-1-4710-6369-5.

- ^ 288 hadith found in 'Fighting for the Cause of Allah (Jihaad)' of Sahih Bukhari.

- ^ Imam Bukhari & Muslim (15 August 2014). Sahih Al-Bukhari Muslim: Arabic – English (English Translation). pp. 114–.

- ^ Muḥammad ibn Ismāʻīl Bukhārī; Muhammad Muhsin Khan (1996). مختصر صحيح البخاري. Darussalam. pp. 602–. ISBN 978-9960-740-80-5.

- ^ Muhammad Muhsin Khan (1971). Sahih Bukhari. Peace Vision. pp. 684–. ISBN 978-1-4710-6369-5.

- ^ Vol. 4, Book 52, Hadith 179

- ^ Hamdaan Publications. Sahih Al-Bukhari. pp. 690–.

- ^ Something Said the Lord Christ. Douglas Chick. pp. 359–. ISBN 978-1-937485-45-0.

- ^ Kailtyn Chick. Islamic Hadith (English Translation). Hamlet Book Publishing. pp. 230–.

- ^ : Sahih al-Bukhari 3587, 3588, 3589 : Book 61, Hadith 96 : Vol. 4, Book 56, Hadith 787

- ^ : Sahih Muslim 2912 d : Book 54, Hadith 79 : Book 41, Hadith 6959

- ^ : Sunan an-Nasa'i 3177 : Book 25, Hadith 93 : Vol. 1, Book 25, Hadith 3179

- ^ : Sunan Abi Dawud 4303 : Book 39, Hadith 13 : Book 38, Hadith 4289

- ^ : Sunan Abi Dawud 4305 : Book 39, Hadith 15 : Book 38, Hadith 4291

- ^ IslamKotob. e061. IslamKotob. pp. 174–. GGKEY:EL7K3HJ1T49.

- ^ Mämmädhäsän Qämbärli (1998). Ärab ädäbi-bädii qaynaqlarında Türk. Mütärcim. p. 17.

- ^ Andrew Rippin (January 2001). The Qurản, Style and Contents. Ashgate. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-86078-700-6.

- ^ Abd Allah Ibn Umar Baydawi; Mahmud Isfahani (October 2001). Nature, man and God in medieval Islam. 1 (2002). BRILL. pp. 989–. ISBN 90-04-12102-1.

- ^ Saheeh al-Jaami as-Sagheer 8170

- ^ David Bade (4 September 2013). Of Palm Wine, Women and War: The Mongolian Naval Expedition to Java in the 13th Century. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 139–. ISBN 978-981-4517-82-9.

- ^ David W. Bade (2002). Khubilai Khan and the Beautiful Princess of Tumapel: The Mongols Between History and Literature in Java. A. Chuluunbat. p. 115.

- ^ Bade, David. Meaning and Truth in Histories. Cambridge University Press, 2013. Cambridge Books Online. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Partial Translation of Sunan Abu-Dawud, Book 37: Battles (Kitab Al-Malahim) Book 37, Number 4292: [4]

- ^ Foster, John (1939). The Church of the Tang Dynasty. Macmillan. p. 13.

- ^ Turkic Language family tree entries provide the information on the Turkic-speaking populations and regions.

- ^ a b Katzner, Kenneth (March 2002). Languages of the World, Third Edition. Routledge, an imprint of Taylor & Francis Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-415-25004-7.

- ^ Across Central Asia, a New Bond Grows – Iron Curtain's Fall Has Spawned a Convergence for Descendants of Turkic Nomad Hordes

- ^ "Türkiye'deki Kürtlerin sayısı!" [The number of Kurds in Turkey!]. Milliyet (in Turkish). 6 June 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Substantial numbers (possibly several millions) of maghrebis of the former Ottoman colonies in North Africa are of Ottoman Turkish descent. Finnish Tatars

- ^ The Karakalpak Gene Pool (Spencer Wells, 2001); and discussion and conclusions at www.karakalpak.com/genetics.html

- ^ Turkic people, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Edition, 2008

- ^ Vasiliev D.D. Graphical fund of Turkic runiform writing monuments in Asian areal, М., 1983, p. 44

- ^ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.) (2005). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Language Family Trees – Altaic". Retrieved 2007-03-18.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Georg, S., Michalove, P.A., Manaster Ramer, A., Sidwell, P.J.: "Telling general linguists about Altaic", Journal of Linguistics 35 (1999): 65–98 Online abstract and link to free pdf

- ^ Turkic peoples, Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Academic Edition, 2008

- ^ "关于回鹘摩尼教史的几个问题". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "元明时期的新疆藏传佛教". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "回鹘文《陶师本生》及其特点". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ 回鹘观音信仰考

- ^ "回鶻彌勒信仰考". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Guide to Russia:Chuvash

- ^ "景教艺术在西域之发现". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ 高昌回鹘与环塔里木多元文化的融合

- ^ 唐代中围景教与景教本部教会的关系

- ^ "景教在西域的传播". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ "新闻_星岛环球网". Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ 7–11 世紀景教在陸上絲綢之路的傳播

- ^ Mayor, Adrienne. The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Princeton University Press.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ Burak, Sansal. "Turkish Jereed (Javelin)". All About Turkey. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ Christensen, karen; Levinson, David. Encyclopedia of World Sport: From Ancient Times to the Present.

{{cite book}}: External link in|ref= - ^ "jigs". dic.academic.ru.

{{cite web}}: External link in|ref=|url=(help)

Further reading

- Alpamysh, H.B. Paksoy: Central Asian Identity under Russian Rule (Hartford: AACAR, 1989)

- H. B. Paksoy (1989). Alpamysh: Central Asian Identity Under Russian Rule. AACAR. ISBN 978-0-9621379-9-0.

- Amanjolov A.S., "History of тhe Ancient Turkic Script", Almaty, "Mektep", 2003, ISBN 9965-16-204-2

- Baichorov S.Ya., "Ancient Turkic runic monuments of the Europe", Stavropol, 1989 (in Russian).

- Baskakov, N.A. 1962, 1969. Introduction to the study of the Turkic languages. Moscow (in Russian).

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009): Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

- Boeschoten, Hendrik & Lars Johanson. 2006. Turkic languages in contact. Turcologica, Bd. 61. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 3-447-05212-0.

- Chavannes, Édouard (1900): Documents sur les Tou-kiue (Turcs) occidentaux. Paris, Librairie d'Amérique et d'Orient. Reprint: Taipei. Cheng Wen Publishing Co. 1969.

- Clausen, Gerard. 1972. An etymological dictionary of pre-thirteenth-century Turkish. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deny, Jean et al. 1959–1964. Philologiae Turcicae Fundamenta. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. 2005. The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8; ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk.)

- Golden, Peter B. An introduction to the history of the Turkic peoples: Ethnogenesis and state-formation in medieval and early modern Eurasia and the Middle East (Otto Harrassowitz (Wiesbaden) 1992) ISBN 3-447-03274-X

- Peter B. Golden (1 January 1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-03274-2.

- Heywood, Colin. The Turks (The Peoples of Europe) (Blackwell 2005), ISBN 978-0-631-15897-4.

- Hostler, Charles Warren. The Turks of Central Asia (Greenwood Press, November 1993), ISBN 0-275-93931-6.

- Ishjatms N., "Nomads In Eastern Central Asia", in the "History of civilizations of Central Asia", Volume 2, UNESCO Publishing, 1996, ISBN 92-3-102846-4.

- Johanson, Lars & Éva Agnes Csató (ed.). 1998. The Turkic languages. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08200-5.

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "The history of Turkic." In: Johanson & Csató, pp. 81–125. Classification of Turkic languages

- Johanson, Lars. 1998. "Turkic languages." In: Encyclopædia Britannica. CD 98. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 5 September. 2007. Turkic languages: Linguistic history.

- Kyzlasov I.L., "Runic Scripts of Eurasian Steppes", Moscow, Eastern Literature, 1994, ISBN 5-02-017741-5.

- Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. (2006). Les Saces: Les « Scythes » d'Asie, VIIIe siècle apr. J.-C. Editions Errance, Paris. ISBN 2-87772-337-2.

- Malov S.E., "Monuments of the ancient Turkic inscriptions. Texts and research", M.-L., 1951 (in Russian).

- Mukhamadiev A., "Turanian Writing", in "Problems Of Lingo-Ethno-History Of The Tatar People", Kazan, 1995 (Азгар Мухамадиев, "Туранская Письменность", "Проблемы лингвоэтноистории татарского народа", Казань, 1995) (in Russian).

- Menges, K. H. 1968. The Turkic languages and peoples: An introduction to Turkic studies. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Öztopçu, Kurtuluş. 1996. Dictionary of the Turkic languages: English, Azerbaijani, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Tatar, Turkish, Turkmen, Uighur, Uzbek. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14198-2

- Samoilovich, A. N. 1922. Some additions to the classification of the Turkish languages. Petrograd.

- Schönig, Claus. 1997–1998. "A new attempt to classify the Turkic languages I-III." Turkic Languages 1:1.117–133, 1:2.262–277, 2:1.130–151.

- Vasiliev D.D. Graphical fund of Turkic runiform writing monuments in Asian areal. М., 198 (in Russian).

- Vasiliev D.D. Corpus of Turkic runiform monuments in the basin of Enisei. М., 1983 (in Russian).

- Voegelin, C.F. & F.M. Voegelin. 1977. Classification and index of the World's languages. New York: Elsevier.

- Khanbaghi, Aptin (2006). The Fire, the Star and the Cross: Minority Religions in Medieval and Early Modern Iran. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1845110567.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Yarshater, Ehsan (2001). Encyclopedia Iranica. Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0933273568.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Turkish Studies - Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan

- Türkçekent Orientaal's links for Turkish Language Learning

- Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages

- Crimean Tatar Internet Resources

New DNA Results

- "Probable ancestors of Hungarian ethnic groups: an admixture analysis"C. R. GUGLIELMINO1, A. DE SILVESTRI2 and J. BERES