Ulster Protestants

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2013) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Total ambiguous (900,000-1,000,000) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northern Ireland | 873,464[citation needed] |

| Republic of Ireland | 27,234[1] |

| Languages | |

| Ulster English, Ulster Scots | |

| Religion | |

| Protestantism (mostly Presbyterianism, Anglicanism, and Methodism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ulster Scots, Irish people, Scottish people, English people | |

Ulster Protestants are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about half the population. Many Ulster Protestants are descendants of the Protestant settlers involved in the early 17th century Ulster Plantation, which introduced the first significant numbers of Protestants into the west and centre of the province. These settlers were mostly Lowland Scottish and Northern English people and predominantly from Galloway, the Scottish Borders and Northumberland.[2]

History

Begun privately in 1606, the Plantation of Ulster became government-sponsored in 1609, with much land for settlement being allocated to the Livery Companies of the City of London. Colonising Ulster with loyal Scottish and English settlers, the vast majority of whom were Protestants, was seen by the ministers of King James as a way to prevent further rebellion in the province, which had been the region of Ireland most resistant to English control during the preceding century. By 1622 there was a total settler population of about 19,000,[3] and by the 1630s somewhere between 50,000[4] and as many as 80,000. Ulster Protestants descend from a variety of lineages, including Scots (some of whose descendants consider themselves Ulster Scots), English, Irish, and Huguenots.[5][6] Another influx of an estimated 20,000 Scottish Protestants, mainly to the coastal counties of Antrim, Down and Londonderry, was a result of the seven ill years of famines in Scotland in the 1690s.[7] This migration decisively changed the population of Ulster, giving it a Protestant majority.[4] While Presbyterians of Scottish descent and origin had already become the majority of Ulster Protestants by the 1660s, when Protestants still made up only a third of the population, they had become an absolute majority in the province by the 1720s.[8]

Divisions between Ulster's Protestants and Irish Catholics have played a major role in the history of Ulster from the 17th century to the present day, especially during the Plantation, the Cromwellian conquest, the Williamite War, the revolutionary period, and the Troubles. Most Ulster Protestants are Presbyterian or Anglican; Scottish colonists were mostly Presbyterian[9] and the English mostly members of the Church of England. Repression of Presbyterians by Anglicans (who followed the Church of Ireland state religion) intensified after the Glorious Revolution, especially after the Test Act of 1703, and was one reason for heavy onward emigration to North America by Ulster Presbyterians during the 18th century (see Scotch-Irish American).[10] Between 1717 and 1775, an estimated 200,000 migrated to what became the United States of America.[11] Some Presbyterians also returned to Scotland during this period, where the Presbyterian Church of Scotland was the state religion. This repression by Anglicans largely ended after the Irish Rebellion of 1798, with the relaxation of the Penal Laws.[12] As Belfast became industrialised in the 19th century, it attracted yet more Protestant immigrants from Scotland.[13] After the partition of Ireland in 1920, the new government of Northern Ireland launched a campaign to entice Protestants from the rest of Ireland to relocate to Northern Ireland, with inducements of state jobs and housing, and large numbers accepted.[14] Because of these migrations, Ulster has a lower proportion of Catholics than the other provinces of Ireland.

Present day

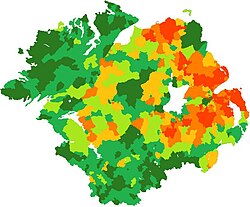

0-10% dark green, 10-30% mid-green,

30-50% light green, 50-70% light orange,

70-90% mid-orange, 90-100% dark orange.

The vast majority of Ulster Protestants live in Northern Ireland, which is part of the present-day United Kingdom. Most tend to support its Union with Great Britain,[15] and are thus known as Unionists, or Ulster Unionists. Unionism is an ideology that (in Ulster) has been divided by some into two camps; Ulster British, who are attached to the United Kingdom and identify primarily as British; and Ulster loyalists, whose politics are primarily ethnic, prioritising their Ulster Protestantism above their British identity.[16][17][18] The Loyal Orders, which include the Orange Order, Royal Black Institution and Apprentice Boys of Derry, are exclusively Protestant fraternal organisations which originated in Ulster and still have most of their membership there.

About 3% of Ulster Protestants live in the three counties of Ulster now in the Republic of Ireland, Cavan, Monaghan, and Donegal, where they make up around a fifth of the Republic's Protestant population.[19] Unlike Protestants in the rest of the Republic, some retain a sense of Britishness, and a small number have difficulty identifying with the independent Irish state.[1][20][21]

Most Ulster Protestants speak Ulster English, and some speak one of the Ulster Scots dialects.[22][23][24] T

See also

References

- ^ a b http://www.seupb.eu/Libraries/Peace_Network_Meetings_and_Events/PN__The_Border_Protestant_Community_and_the_EU_PEACE_Programmes__100205_A_report_to_the_Peace_II_Monitoring_Committee.sflb.ashx

- ^ "'Sheep stealers from the north of England': the Riding Clans in Ulster by Robert Bell". History Ireland.

- ^ Canny, Making Ireland British, p. 211

- ^ a b "From Catastrophe to Baby Boom – Population Change in Early Modern Ireland 1641-1741". The Irish Story.

- ^ "Ulster blood, English heart – I am what I am". nuzhound.com.

- ^ "The Huguenots in Lisburn". Culture Northern Ireland.

- ^ K. J. Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The “Ill Years” of the 1690s (Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638873, pp. 178-9.

- ^ Karen Cullen, Famine in Scotland: The 'Ill Years' of the 1690s, pp. 176-179

- ^ Edmund Curtis, p. 198.

- ^ "The Irish at Home and Abroad: Scots-Irish in Colonial America / Magazine / Irish Ancestors / The Irish Times". irishtimes.com.

- ^ Fischer, David Hackett, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America Oxford University Press, USA (14 March 1989), p. 606; Parke S. Rouse, Jr., The Great Wagon Road, Dietz Press, 2004, p. 32, and Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, p. 180.

- ^ James Connolly. "James Connolly: July the 12th (1913)". marxists.org.

- ^ "The Scots in Victorian and Edwardian Belfast". euppublishing.com.

- ^ "Protestant population decline". The Irish Times. 22 September 2014.

- ^ http://www.kevinbyrne.ie/pubs/ByrneOMalley2013a.pdf

- ^ "Unionists, Loyalists, and Conflict Transformation in Northern Ireland".

- ^ http://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/staff/michael_gallagher/HowManyNations95.pdf

- ^ Andrew White. "White, A. (2007) Is contemporary Ulster unionism in crisis? Changes in unionist identity during the Northern Ireland Peace Process. Irish Journal of Sociology, 16 (1), pp. 118-135".

- ^ Darach MacDonald. "Frontier Post". darachmac.blogspot.dk.

- ^ "Living behind the Emerald". Independent.ie.

- ^ "Orange County, Irish-style..." Independent.ie.

- ^ Gregg R.J. (1972) "The Scotch-Irish Dialect Boundaries in Ulster" in Wakelin M. F., Patterns in the Folk Speech of The British Isles, London

- ^ C. Macafee (2001) "Lowland Sources of Ulster Scots" in J.M. Kirk & D.P. Ó Baoill, Languages Links: The Languages of Scotland and Ireland, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona, Belfast, p121

- ^ J. Harris (1985) Phonological Variation and Change: Studies in Hiberno English, Cambridge, p15