United Palace

Loew's 175th Street Theatre | |

(2014) | |

| |

| Address | 4140 Broadway between West 175th and West 176th Streets Washington Heights, Manhattan New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°50′47″N 73°56′17″W / 40.846412°N 73.938193°W |

| Owner | United Christian Evangelistic Association[1] |

| Capacity | 1930: 3,444[2] or 3,661;[3] 2007: 3,293[4] |

| Current use | church; live music venue |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 1930 |

| Architect | Thomas W. Lamb |

| Website | |

| http://www.unitedpalace.org | |

The United Palace is a church, live music venue, and non-profit cultural center located at 4140 Broadway between West 175th and 176th Streets in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. Built in 1930 as Loew's 175th Street Theatre, the venue was originally a movie palace designed by architect Thomas W. Lamb. Its lavishly eclectic interior decor was supervised by Harold Rambusch.[5][6][7][8] The theater originally presented films and live vaudeville and operated continuously until closed by Loew's in 1969. That same year it was purchased for over a half million dollars by the television evangelist Rev. Frederick J. Eikerenkoetter II, better known as Reverend Ike. The theater became the headquarters of his United Church Science of Living Institute and was renamed the Palace Cathedral, sometimes also called "Reverend Ike's Prayer Tower".[3] It was completely restored and still continues to be maintained by the United Church.[9]

Architecture

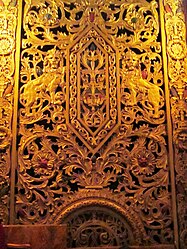

The architectural style of the terra-cotta-faced theater has been described as "Byzantine-Romanesque-Indo-Hindu-Sino-Moorish-Persian-Eclectic-Rococo-Deco" by David W. Dunlap of the New York Times,[4] who wrote later that Lamb borrowed from "the Alhambra in Spain, the Kailasa rock-cut shrine in India, and the Wat Phra Keo temple in Thailand, adding Buddhas, bodhisattvas, elephants, and honeycomb stonework in an Islamic pattern known as muqarnas."[8] The AIA Guide to New York City calls it "Cambodian neo-Classical" and invites a comparison to Lamb's Loew's Pitkin Theatre in Brownsville, Brooklyn,[10] while New York Times reporter Nathaniel Adams called it simply a "kitchen-sink masterpiece." Lamb himself wrote that "Exotic ornaments, colors and scenes are particularly effective in creating an atmosphere in which the mind is free to frolic and becomes receptive to entertainment."[6]

The interior of the building features a "palatial" staircase.[3] and reflects the western obsession with exotic lands and cultures that was fashionable in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The interior is decorated with filigreed walls and ceilings, illuminated with indirect, recessed lighting from within and behind the walls. The rich decor is enhanced by the addition of authentic Louis XV and XVI furnishings and a collection of other works of art.[11]

The theater still looks very much as it did when it first opened; the only major change that Rev. Ike made was adding in the 1970s a cuppola or prayer tower on the building's northeast corner, at Wadsworth Avenue and West 176th Street, topped by a "Miracle Star of Faith," visible from the George Washington Bridge and New Jersey.

History

Loews 175th Street Theatre was built as one of the Loew's Wonder Theatres, the company's five extravagant and spacious flagships throughout the New York City area. The other four theaters are Loew's Jersey in Jersey City (1929) and Loew's Kings in Brooklyn (1929), both now used as performing arts centers;[12][13] and Loew's Paradise in the Bronx (1929) and Loew's Valencia in Queens (1929), both now used as churches.[14]

All five theaters featured identical "Wonder Morton" theatre pipe organs manufactured by the Robert Morton Organ Company of Van Nuys, California. Each organ featured a four-manual console and 23 ranks of pipes. The organ in the United Palace was restored c.1970 after almost 25 years of disuse, and was utilized by the church in its services. It remains in the theater but is not currently functioning due to water damage.[3]

The 175th Street Theatre seated over 3,000 people and opened on February 22, 1930. The first program included the MGM film Their Own Desire. starring Norma Shearer, and Pearls, a live musical stage revue starring vaudevillians Shaw and Lee (Al Shaw and Sam Lee). Loew's closed the theater 39 years later in March 1969 with a showing of 2001: A Space Odyssey.[3]

Church

In 1969, as the era of grand movie palaces was coming to an end, the theatre was purchased by televangelist Rev. Ike, who renamed the building the United Palace.[15] As a successful "prosperity preacher," Rev. Ike was able to restore the theatre as his congregation grew through syndicated radio and television shows.[16]

The church's congregation is now called The United Palace House of Inspiration (UPHI), and is an all-inclusive, non-denominational spiritual community[17] led by Xavier Eikerenkoetter, the son of Reverend Ike, who took over when his father died.[18] Eikerenkoetter renamed the congregation to UPHI. It offers a Sunday service every week, community circles and classes, a neighborhood fellowship that includes a choir and dance ministry, outreach and youth programs and a volunteer ministry.

The non-profit United Palace of Cultural Arts (UPCA) was founded by Eikerenkoetter in 2012 and functions as a community arts center. It presents performing arts events and screenings of classic movies.[19]

Performance venue

A series of rock concerts presented at the United Palace were produced by Andy Feltz, formerly of the Beacon Theatre.[4] Musical performers since 2007 include Vampire Weekend, Eddie Vedder, Neil Young, Sonic Youth, Bloc Party, Bob Dylan, Adele, The Smashing Pumpkins, Beck, Sigur Rós, Jackson Browne, Alex Campos, Björk, Allman Brothers Band,[7] Iggy and the Stooges,[7] Modest Mouse,[4] The Black Crowes, Arcade Fire and Kraftwerk. The United Palace also presents concerts by Latino artists.

In 2007, Sir Simon Rattle appeared at the theater conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in Igor Stravinsky's ballet The Rite of Spring danced by public school students and choreographed by Royston Maldoom.[7] The following year, a performance of Leonard Bernstein's Mass was given as part of the celebration of the 90th anniversary of that composer's birth.[20] In addition, recitals, classes and lectures have also been presented at the theatre, and the TV show Smash has used the theatre to film its fictional Broadway production Bombshell.[21]

In 2013 limited film screenings returned to the Palace. As of 2001, the projection booth still had three six-foot tall Simplex projectors with Peerless arclight housings.[6] In 2013 money was raised to install digital projection in the theatre. The first film presented in the new format was the 1941 Warner Bros classic Casablanca.[22]

Gallery

- Exterior

-

The corner of Broadway and West 175th Street

-

The vertical sign

-

The building's dome at the corner of Wadsworth Avenue and West 176th Street, featuring the "Miracle Star of Faith"

- Interior

-

The base of a column in the lobby

-

A column on the main staircase to the mezzanine

-

The base of a column in the mezzanine

-

A detail from a mezzanine wall

References

Notes

- ^ "4140 Broadway, Manhattan" New York City Geographic Information Services map. Accessed: June 1, 2014

- ^ Moritz, Owen. (May 2, 2004) "Loew's Legacy is Alive on Screens" New York Daily News

- ^ a b c d e "United Church: 'The Palace Cathedral'" in New York City Organ Project New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists

- ^ a b c d Dwyer, Jim (May 2, 2007), "With Indie Rock on 175th St., City's Reinvention Rolls Uptown", The New York Times

- ^ Adams, Nathaniel (January 15, 2015). "Across the New York Area, Restoring 'Wonder Theater' Movie Palaces to Glory". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d .Dunlap, David W. (April 13, 2001), "Xanadus Rise to a Higher Calling", The New York Times

- ^ a b c d Atamian, Christopher (November 11, 2007). "'Rite of Spring' as Rite of Passage". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (2004). From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan's Houses of Worship. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-12543-7., p.286

- ^ Lehman-Haupt, Christopher. (July 30, 2009) "Reverend Ike, Who Preached Riches, Dies at 74" The New York Times

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7., p.568

- ^ "United Palace Theatre History". United Palace Theatre website.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ Alberts, Hana R. (28 May 2014). "See the Amazing Restoration of Flatbush's 1920s Movie Palace". CurbedNYC. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ^ Kings Theatre website

- ^ Krefft, Jason R. Bryan; and Roe, Ken. "Loew's Valencia Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 2010-09-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Diamond, Bruce (May 11, 2012). "United Palace Cathedral may see new life as community arts center". New York Daily News.

- ^ Hagerty, Barbara Bradley (July 30, 2009). "The Everlasting Message Of Reverend Ike". NPR.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - ^ "United Palace House of Inspiration". United Palace House of Inspiration website.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help) - ^ McLellan, Dennis (July 31, 2009). "Reverend Ike dies at 74; minister preached gospel of prosperity". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ United Palace of Cultural Arts website

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (October 26, 2008). "Bernstein Mass Project, Youthful Choristers Imparting New Life". The New York Times.

- ^ Kemp, Kris. "How to Get More Work as a Background Actor (Extra) in New York City"

- ^ "Success! $49K Raised to return film to the Palace". United Palace. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|website=(help)