United States Marshals Service

| United States Marshals Service | |

|---|---|

Variant flag of the U.S. Marshals Service | |

Badge of the U.S. Marshals Service | |

Flag of the U.S. Marshals Service | |

| Common name | U.S. Marshals |

| Abbreviation | USMS |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | September 24, 1789 |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Federal agency | United States |

| Operations jurisdiction | United States |

| Constituting instrument |

|

| General nature | |

| Operational structure | |

| Headquarters | Arlington County, Virginia, U.S. |

| Sworn members | 94 U.S. marshals, 3,953 deputy U.S. marshals and criminal investigators[2] |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | Department of Justice |

| Website | |

| usmarshals.gov | |

The United States Marshals Service (USMS) is a U.S. federal law enforcement agency within the U.S. Department of Justice (see 28 U.S.C. § 561). The office of U.S. Marshals is the oldest American federal law enforcement office. The U.S. Marshals office was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789. It assumed its current name in 1969.[4]

The Marshals Service is part of the executive branch of government, and is the enforcement arm of the U.S. federal courts. The U.S. Marshals are the primary agency for fugitive operations. U.S. Marshals are also responsible for the protection of officers of the court, court buildings and the effective operation of the judiciary. The service also assists with court security, prisoner transport, and serves arrest warrants.

History

Origins

The office of United States marshal was created by the Judiciary Act on September 24, 1789. The act specifically determined that the U.S. Marshals' primary function was to execute all lawful warrants issued to him and under the authority of the United States. It defined marshals as officers of the courts charged with assisting federal courts in their law-enforcement functions.

The text of Section 27 of the Judiciary Act reads:

And be it further enacted, That a marshal shall be appointed in and for each district for a term of four years, but shall be removable from office at pleasure, whose duty it shall be to attend the district and circuit courts when sitting therein, and also the Supreme Court in the district in which that court shall sit. And to execute throughout the district, all lawful precepts directed to him, and issued under the authority of the United States, and he shall have the power to command all necessary assistance in the execution of his duty, and to appoint as shall be occasion, one or more deputies.[5]

The Marshals Service itself, as a federal agency, was not created until 1969. It succeeded the Executive Office for United States Marshals, itself created in 1965 as "the first organization to supervise U.S. Marshals nationwide".[4][6]

In a letter to Edmund Randolph, the first United States Attorney General, President George Washington wrote:

Impressed with a conviction that the due administration of justice is the firmest pillar of good Government, I have considered the first arrangement of the Judicial department as essential to the happiness of our Country, and to the stability of its political system; hence the selection of the fittest characters to expound the law, and dispense justice, has been an invariable object of my anxious concern.

Many of the first U.S. Marshals had already proven themselves in military service during the American Revolution. Among the first marshals were John Adams's son-in-law Congressman William Stephens Smith for the district of New York, another New York district marshal, Congressman Thomas Morris, and Henry Dearborn for the district of Maine.

From the nation's earliest days marshals were permitted to recruit special deputies as local hires or as temporary transfers to the Marshals Service from other federal law-enforcement agencies. Marshals were also authorized to swear in a posse to assist with manhunts and other duties ad hoc. Marshals were given extensive authority to support the federal courts within their judicial districts, and to carry out all lawful orders issued by federal judges, Congress, or the President.

The marshals and their deputies served writs (e.g., subpoenas, summonses, warrants), and other process issued by the courts, made all the arrests, and handled all federal prisoners. They also disbursed funds as ordered by the courts. Marshals paid the fees and expenses of the court clerks, U.S. Attorneys, jurors, and witnesses. They rented the courtrooms and jail space and hired the bailiffs, criers, and janitors. They made sure the prisoners were present, the jurors were available, and that the witnesses were on time.

When President George Washington set up his first administration, and the first Congress began passing laws, both quickly discovered an inconvenient gap in the constitutional design of the government: It had no provision for a regional administrative structure stretching throughout the country. Both the Congress and the executive branch were housed at the national capital; no agency was established or designated to represent the federal government's interests at other localities. The need for a regional organization quickly became apparent. Congress and the President solved part of the problem by creating specialized agencies, such as customs and revenue collectors, to levy tariffs and taxes, yet there were numerous other jobs that needed to be done. The only officers available to do them were the marshals and their deputies.

The marshals thus provided local representation for the federal government within their districts. They took the national census every decade through 1870. They distributed presidential proclamations, collected a variety of statistical information on commerce and manufacturing, supplied the names of government employees for the national register, and performed other routine tasks needed for the central government to function effectively.

Enforcement roles, U.S. territory

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2013) |

During the settlement of the American West, marshals often served as the main source of day-to-day law enforcement in various parts of the west that had no local government of their own. Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and Dallas Stoudenmire are examples of well-known marshals.

In modern times

Congress, the president, and governors have called on the marshals for over 200 years to carry out unusual or extraordinary missions, such as registering enemy aliens in wartime, sealing the American border against armed expeditions from foreign countries, and, at times during the Cold War, swapping spies with the Soviet Union, and also retrieving North Carolina's copy of the Bill of Rights.[7] Individual deputy marshals, particularly in the American West, have been seen as legendary heroes in the face of rampant lawlessness (see Famous marshals, below).

Marshals arrested the infamous Dalton Gang in 1893, helped suppress the Pullman Strike in 1894, enforced Prohibition during the 1920s, and have protected American athletes at recent Olympic Games. Marshals protected the refugee boy Elián González before his return to Cuba in 2000, and have protected abortion clinics as required by federal law. The Marshals Service has been responsible for law enforcement among U.S. personnel in Antarctica since 1989.[8]

One of the more onerous jobs the marshals were tasked with was the recovery of fugitive slaves, as required by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. They were also permitted to form a posse and to deputize any person in any community to aid in the recapture of fugitive slaves. Failure to cooperate with a marshal resulted in a $5000 fine and imprisonment, a significant penalty in those days. The Oberlin-Wellington Rescue was a celebrated fugitive-slave case involving U.S. marshals. James Batchelder was the second marshal killed in the line of duty. Batchelder, along with others, was preventing the rescue of fugitive slave Anthony Burns in Boston in 1854.

The marshals were on the front lines of the civil rights movement in the 1960s, mainly providing protection to volunteers. In September 1962, President John F. Kennedy ordered 127 marshals to accompany James Meredith, an African American who wished to register at the segregated University of Mississippi. Their presence on campus provoked riots at the university, requiring President Kennedy to federalize the Mississippi National Guard to pacify the crowd, but the marshals stood their ground, and Meredith registered. Marshals provided continuous protection to Meredith during his first year at Ole Miss, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy later proudly displayed a deputy marshal's dented helmet in his office. U.S. marshals also protected black schoolchildren integrating public schools in the South. Artist Norman Rockwell's famous painting The Problem We All Live With depicted a tiny Ruby Bridges being escorted by four towering U.S. marshals in 1964.

Except for suits by incarcerated persons, non-prisoner litigants proceeding in forma pauperis, or (in some circumstances) by seamen, U.S. marshals no longer serve process in private civil actions filed in the U.S. district courts. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure process may be served by any U.S. citizen over the age of 18 who is not a party involved in the case.

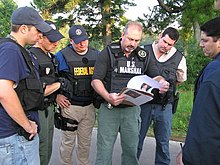

Duties

The Marshals Service is responsible for apprehending wanted fugitives, providing protection for the federal judiciary, transporting federal prisoners (see JPATS), protecting endangered federal witnesses, and managing assets seized from criminal enterprises. The Marshals Service is responsible for 55.2% of arrests of federal fugitives. Between 1981 and 1985, the Marshals Service conducted Fugitive Investigative Strike Team operations to jump-start fugitive capture in specific districts. In 2012, U.S. marshals captured over 36,000 federal fugitives and cleared over 39,000 fugitive warrants.[9]

The United States Marshals Service also executes all lawful writs, processes, and orders issued under the authority of the United States, and shall command all necessary assistance to execute its duties.

U.S. marshals also have the common law-based power to enlist any willing civilians as deputies.[citation needed] In the Old West this was known as forming a posse, although under the Posse Comitatus Act, they cannot use troops for law enforcement duties while in uniform representing their unit, or the military service. However if serviceman/woman is off duty, wearing civilian clothing, and willing to assist a law enforcement officer on his/her own behalf, it is acceptable.[citation needed]

Lastly, Title 28 USC Chapter 37 § 564. authorizes United States marshals, deputy marshals and such other officials of the Service as may be designated by the Director, in executing the laws of the United States within a State, to exercise the same powers which a sheriff of the State may exercise in executing the laws thereof.[10]

Organization

The United States Marshals Service is based in Arlington, Virginia, and, under the authority and direction of the Attorney General, is headed by a Director, who is assisted by a Deputy Director. USMS Headquarters provides command, control, and cooperation for the disparate elements of the service.

Headquarters

- Director of the U.S. Marshals Service: Stacia Hylton

- Deputy Director of the U.S. Marshals Service

- Chief of Staff

- Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO)

- Office of Public Affairs (OPA)

- Office of Congressional Affairs (OCA)

- Office of Internal Communications (OIC)

- Office of General Counsel (OGC)

- Office of Inspection (OI)

- Administration Directorate (ADA)

- Training Division (TD)

- Human Resources Division (HRD)

- Information Technology Division (ITD)

- Management Support Division (MSD)

- Financial Services Division (FSD)

- Asset Forfeiture Division (AFD)

- Operations Directorate (ADO)

- Judicial Security Division (JSD)

- Investigative Operations Division (IOD)

- Witness Security Division (WSD)

- Justice Prisoner and Alien Transportation System (JPATS)

- Tactical Operations Division (TOD)

- Special Operations Group (SOG)

- Prisoner Operations Division (POD)

- Deputy Director of the U.S. Marshals Service

Districts

The U.S. court system is divided into 94 federal judicial districts, each with a district court. For each district there is a presidentially-appointed and Senate-confirmed United States marshal, a chief deputy U.S. marshal (GS-15) (and an assistant chief deputy U.S. marshal (GS-14) in certain larger districts), supervisory deputy U.S. marshals (GS-13),[11] and as many deputy U.S. marshals (GS-7 and above)[11] and special deputy U.S. marshals as needed. In the United States federal budget for 2005, funds for 3,067 deputy marshals and criminal investigators were provided. The U.S. marshal for United States courts of appeals (the 13 circuit courts) is the U.S. marshal in whose district that court is physically located.

The director and each United States marshal are appointed by the President of the United States and subject to confirmation by the United States Senate. The District U.S. marshal is traditionally appointed from a list of qualified law enforcement personnel for that district or state. Each state has at least one district, while several larger states have three or more.

Deputy U.S. marshals

Training and job duties

U.S. Marshals Service hiring is competitive and comparable to the selection process for Special Agent positions in sister agencies. Typically less than 5% of qualified applicants are hired [citation needed] and must possess at a minimum a four-year bachelor degree or competitive work experience (which is usually three or more years at a local or state police department). While the USMS's hiring process is not entirely in the public domain, applicants must pass a written test, an oral board interview, an extensive background investigation, a medical examination and drug test, and multiple Fitness In Total (FIT) exams to be selected for training.[citation needed]

Deputy U.S. marshals complete a 19-week training program at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Glynco, Georgia.

Deputy U.S. marshals start their careers as 0082 basic deputy U.S. marshals at the GS-7 pay grade.[11] After the first year in grade, they are promoted to GS-9, the following year GS-11, and finally journeyman GS-12 (automatic progression to the grade of GS-13 is under consideration).[citation needed] Once deputies reach the GS-11 pay grade, they are reclassified as 1811 Criminal Investigators.[12] Criminal Investigators work additional hours and receive an additional 25% Law Enforcement Availability Pay on top of their base pay.

Deputies perform criminal investigations, execute warrants, and other investigative operations. They also protect government officials, process seized assets of crime rings for investigative agencies, and relocate and arrange new identities for federal witnesses in the United States Federal Witness Protection Program, which is headed by the USMS.[citation needed] After Congress passed the Adam Walsh Act, the U.S. Marshals Service was chosen to head the new federal sex offender tracking and prosecution hot team.[citation needed].

Misconceptions:

- Federal air marshals are not deputy U.S. marshals. The TSA-Federal Air Marshal Program is not affiliated with the U.S. Marshals Service

- Deputy marshals do not guard Federal buildings. Homeland Security (DHS-FPS) is charged with protecting the Federal facilities. Court Security Officers (CSO) handle entrance and courthouse security.

Titles

- Director of the United States Marshals Service: originally titled the Chief United States Marshal, top executive of the entire U.S. Marshals Service[11]

- United States Marshal: for the top executive Marshals Service position (political appointment) in a federal judicial district

- Chief Deputy United States Marshal: the senior career manager for the federal judicial district who is responsible for management of the Marshals office and staff

- Supervisory Deputy United States Marshal: for positions in the Marshals Service responsible for the supervision of three or more deputy U.S. marshals and clerks

- Deputy United States Marshal: for all nonsupervisory positions classifiable to this series

Inspector

This title was created for promotions within the service usually for senior non-supervisory personnel. Senior deputy U.S. marshals (DUSM) assigned to the Witness Protection Program are given the title Inspector. Senior DUSMs assigned to regional fugitive task forces or working in special assignments requiring highly skilled criminal investigators often receive the title Inspector. Deputy marshals assigned to the The Organized Crime Drug Enforcement (OCDETF) department within the USMS also hold the title of Senior Inspector. Inspectors receive a GS-13 pay grade level. The titles of Senior Inspector and Chief Inspector are also sometimes used in the service for certain assignments and positions within the agency.

Special deputy U.S. marshals

The Director of the Marshals Service is authorized by (authorizing Director of Marshals Service to appoint "such employees as are necessary to carry out the powers and duties of the Service") to deputize the following individuals to perform the functions of deputy marshals: selected officers or employees of the Department of Justice; federal, state or local law enforcement officers; members of the United States Coast Guard;[citation needed] when appropriate, private security personnel to provide courtroom security for the Federal judiciary; and other persons designated by the Associate Attorney General.[13]

Court security officers

Court security officers are contracted former law enforcement officers who receive limited deputations as armed special deputy marshals and play a role in courthouse security.[14] Using security screening systems, CSOs attempt to detect and intercept weapons and other prohibited items that individuals attempt to bring into federal courthouses. There are more than 4,700 CSOs with certified law enforcement experience deployed at more than 400 federal court facilities in the United States and its territories.

Detention enforcement officer

DEOs (1802s) are responsible for the care of prisoners in USMS custody. They also are tasked with the responsibility of conducting administrative remedies for the U.S. marshal. DEOs can be seen transporting, booking and securing federal prisoners while in USMS custody. They also provide courtroom safety and cell block security.

Detention enforcement officers are deputized and fully commissioned federal law enforcement officers by the U.S. marshal. They are authorized to carry firearms and conduct all official business on behalf of the agency. Not all districts employ detention enforcement officers.

Specialized units

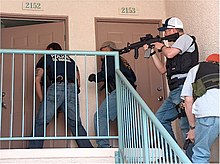

Special Operations Group (SOG)

The Special Operations Group (SOG) is a specially trained and highly disciplined tactical unit of the US Marshals Service. It is a self-supporting response team capable of responding to emergencies anywhere in the United States or its territories. Most of the deputy marshals who have volunteered to be SOG members serve as full-time deputies in Marshals Service offices throughout the nation, and they remain on call 24 hours a day for SOG missions. The SOG also maintains a small, full-time operational cadre stationed at the Marshals Service Tactical Operations Center at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. There, all SOG deputies undergo extensive, specialized training in tactics and weaponry. These deputies must meet rigorous physical and mental standards. The group's missions include: apprehending fugitives; protecting dignitaries; providing court security; transporting high-profile and dangerous prisoners; providing witness security; and seizing assets.Members of the U.S. Marshal SOG Teams are armed with M1911A1 Springfield pro rail Pistol (.45 ACP). Marshals are also equipped with AR-15s and 12-gauge Remington 870 shotguns.

As a less-than-lethal option, marshals are armed with the ASP batons and OC pepper sprays.

Firearms

The primary handgun for marshals is the Glock pistols in .40 S&W caliber (22, 23, 27), and each deputy may carry a backup handgun of their choice if it meets certain requirements.[15]

Line of duty deaths

More than 200 U.S. marshals, deputy marshals, and special deputy marshals have been slain in the line of duty since Marshal Robert Forsyth was shot dead by an intended recipient of court papers in Augusta, Georgia, on January 11, 1794.[16] He was the first U.S. government Law Officer killed in the line of duty.[17] The dead are remembered on an Honor Roll permanently displayed at Headquarters.

Scandals

On March 26, 2009, the body of Deputy U.S. Marshal Vincent Bustamante was discovered in Juarez, Mexico, according to the U.S. Marshals Service. Bustamante, who was accused of stealing and pawning government property, was a fugitive from the law at the time of his death. Chihuahua State Police said the body had multiple wounds to the head – apparently consistent with an execution-style shooting.[18]

In January 2007, Deputy U.S. Marshal John Thomas Ambrose was charged with theft of Justice Department property, disclosure of confidential information, and lying to federal agents during an investigation. Deputy Ambrose had been in charge of protecting mobster-turned-informant Nicholas Calabrese, who was instrumental in sending three mob bosses to prison for life.[19] A federal jury convicted Ambrose on April 27, 2009, of leaking secret government information concerning Calabrese to William Guide, a family friend and former Chicago police officer who had also served time in prison for corruption. Ambrose also was convicted of theft of government property but acquitted of lying to federal agents.[20] On October 27, 2009, Ambrose was sentenced to serve four years in prison.[21]

Racial discrimination

In 1998, retired Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal Matthew Fogg won a landmark EEO and Title VII racial discrimination and retaliation lawsuit against the Justice Department, for which he was awarded $4 million. The jury found the entire Marshals Service to be a "racially hostile environment" which discriminates against blacks in its promotion practices. U.S. District Judge Thomas Penfield Jackson summarized the jurors' decision by stating that they felt there was an "atmosphere of racial disharmony and mistrust within the United States Marshal Service".[22][23] As of 2011, Fogg is president of "Bigots with Badges",[23] and executive director of CARCLE (Congress Against Racism and Corruption in Law Enforcement), and is also associated with Law Enforcement Against Prohibition (LEAP), a drug law reform organization of law enforcement officers.[24]

Criticism

An audit by the Office of Inspector General (OIG) (November 2010) of the Justice Department found "weaknesses in the USMS's efforts to secure federal court facilities in the six USMS district offices we visited".[25]

The report found, among other things, that the USMS Judicial Security Division had contracted private security firms to provide CSOs (Court Security Officers) without having completed background checks. Another incident involved the USMS awarding a $300 million contract to a firm that had a known history of numerous criminal activities leading to convictions for mail fraud and bank fraud and false insurance claims in addition to a civil judgment against its Chief Financial Officer.

Technical problems included CSOs not being properly trained on security screening equipment, which also meant equipment not being used. The OIG noted that in February 2009, several courthouses failed to detect mock explosives sent by USMS HQ in order to test security procedures. They also found that eighteen percent of CSOs had outdated firearms qualifications.

Notable marshals

- Jesse D. Bright (1812–1875), U.S. marshal for Indiana; later served as U.S. senator for that state

- Seth Bullock (1849–1919), businessman, rancher, sheriff for Montana, sheriff of Deadwood, South Dakota, U.S. marshal of South Dakota

- John F. Clark, U.S. Marshals Service Director and U.S. Marshal for the Eastern District of Virginia

- Charles Francis Colcord (1859–1934), rancher, businessman and marshal for Oklahoma

- Phoebe Couzins (1839–1913), lawyer, first woman appointed to the U.S. Marshals

- Henry Dearborn (1751–1829), marshal for the District of Maine

- Frederick Douglass (1818–1895), former slave and noted abolitionist leader, appointed U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia in 1877

- Morgan Earp (1851–1882), deputy U.S. marshal, Tombstone, Arizona, appointed by his brother Wyatt

- Virgil Earp (1843–1905), deputy U.S. marshal, Tombstone, Arizona

- Wyatt Earp (1848–1929), deputy U.S. marshal (appointed to his brother Virgil Earp's place by the Arizona Territorial Governor)

- Richard Griffith (1814–1862), Brigadier General in the Confederacy during the Civil War

- Wild Bill Hickok (1837–1876), noted Western lawman, who served as a deputy U.S. marshal at Fort Riley, Kansas in 1867–1869

- Bass Reeves (July 1838 – January 1910) is thought by most to be one of the first Black men to receive a commission as a U.S. deputy marshal west of the Mississippi River. Before he retired from federal service in 1907, Reeves had arrested over 3,000 felons.

- Ward Hill Lamon (1826–1893), friend, law partner and frequent bodyguard of President Abraham Lincoln, who appointed him U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia.

- J. J. McAlester (1842–1920), U. S. marshal for Indian Territory (1893–1897), Confederate Army captain, merchant in and founder of McAlester, Oklahoma as well as the developer of the coal mining industry in eastern Oklahoma, one of three members of the first Oklahoma Corporation Commission (1907–1911) and the second Lieutenant Governor of Oklahoma (1911–1915).

- Benjamin McCulloch (1811–1862), U.S. marshal for Eastern District of Texas; became a brigadier general in the army of the Confederate States during the American Civil War

- Henry Eustace McCulloch (1816–1895), U.S. marshal for Eastern District of Texas. Brother of Benjamin McCulloch; also a Confederate General

- James J. P. McShane (1909–1968), Appointed U.S. marshal for the District of Columbia by President John F. Kennedy then named chief marshal in 1962

- John W. Marshall, U.S. marshal for the Eastern District of Virginia (1994–1999), first African-American to serve as Director of the U.S. Marshals Service (1999–2001)

- Bat Masterson (1853–1921), noted Western lawman; deputy to US marshal for Southern District of New York, appointed by Theodore Roosevelt

- Joseph Meek (1810–1875), territorial marshal for Oregon

- Thomas Morris (1771–1849), marshal for New York District.

- David Neagle, Shot Chief Justice of California David S. Terry to protect US Supreme Court Justice Stephen Johnson Field resulting in US Supreme Court decision In re Neagle

- Henry Massey Rector (1816–1899), marshal for Arkansas, later governor of that state

- Porter Rockwell (c.1813–1878), deputy marshal for Utah

- William Stephens Smith (1755–1816), 1789 U.S. marshal for New York district and son-in-law of President John Adams

- Dallas Stoudenmire (1845–1882), successful city marshal who tamed and controlled a remote, wild and violent town of El Paso, Texas; became U.S. marshal serving West Texas and New Mexico Territory just before his death

- Heck Thomas (1850–1912), Bill Tilghman (1854–1924), and Chris Madsen (1851–1944), the legendarily fearless "Three Guardsmen" of the Oklahoma Territory

- Cal Whitson (1845-1926), one-eyed deputy marshal for the Oklahoma Territory. Rooster Cogburn of the novel and film True Grit is largely based on Whitson

- William F. Wheeler (1824–1894), marshal for the Montana Territory

- James E. Williams (1930–1999), marshal for South Carolina, Medal of Honor recipient

Fugitive programs

15 Most Wanted

The Marshals Service publicizes the names of wanted persons it places on the list of U.S. Marshals 15 Most Wanted Fugitives,[26] which is similar to and sometimes overlaps the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list or the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives Most Wanted List, depending on jurisdiction.[27]

The 15 Most Wanted Fugitive Program was established in 1983 in an effort to prioritize the investigation and apprehension of high-profile offenders who are considered to be some of the country's most dangerous fugitives. These offenders tend to be career criminals with histories of violence or whose instant offense(s) pose a significant threat to public safety. Current and past fugitives in this program include murderers, sex offenders, major drug kingpins, organized crime figures, and individuals wanted for high-profile financial crimes.

Major cases

The Major Case Fugitive Program was established in 1985 in an effort to supplement the successful 15 Most Wanted Fugitive Program. Much like the 15 Most Wanted Fugitive Program, the Major Case Fugitive Program prioritizes the investigation and apprehension of high-profile offenders who are considered to be some of the country's most dangerous individuals. All escapes from custody are automatically elevated to Major Case status.[28]

Popular culture

Literature

- The fictional character Morgan Kane is described as a US marshal in more than 15 of the 83 books in the Morgan Kane book series, penned by Louis Masterson.

- 1996 short story "Karen Makes Out" and the novel Out of Sight by Elmore Leonard tells the story of a romance between a U.S. marshal and a bank robber. In 1998, the book was made into a movie. The character of the U.S. marshal later appeared in the short-lived TV series Karen Sisco.

- The 2003 novel Shutter Island features two of its main characters as U.S. marshals. It was adapted into film in 2010.

- Anita Blake is a U.S. marshal in a special branch dealing with supernatural crimes in the Vampire Hunter series by Laurell K. Hamilton. Robert B.

TV

- United States Marshal (originally titled "Sheriff of Cochise") was a 1958-1960 series about Marshal Frank Morgan (John Bromfield). The series was set in the American southwest and featured contemporary stories about crime in the 1950s.

- The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp is a series loosely based on the adventures of frontier marshal Wyatt Earp that ran from 1955 to 1961.

- From 1955 to 1975 Gunsmoke ran on CBS, about Matt Dillon, a U.S. marshal for Dodge City, Kansas. Dillon was played by James Arness, who died June 3, 2011, and who was awarded two honorary US marshal badges by the Marshals Service.[29]

- The American/Australian science-fiction television series Time Trax – aired from 1993-1994 – featured time-traveling police detective Darien Lambert from two centuries in the future, traveling back to present day to apprehend fugitives plotting misdeeds with 22nd-century technology and return them to their proper time. His cover in present day was as a U.S. marshal, as it is the role of that office to apprehend fugitives.

- Beginning in 2004, the character Edward Mars in Season 1 and Season 6 of the TV series Lost portrays a U.S. marshal obsessed with apprehending Kate Austen, a character who has murdered her abusive stepfather and previously escaped from the same marshal.

- In 2006 the SciFi Channel launched the original series Eureka in which the main protagonist is a United States marshal named Jack Carter, and set in the fictional town of Eureka. Jack stumbles on the highly secure location where the government works on super high-tech programs, and in the course of assisting with an investigation, becomes the town sheriff.

- In 2008, USA Network (owned by NBC) launched In Plain Sight, a drama showcasing the United States Federal Witness Protection Program (WITSEC).

- Since 2008, A&E Network has aired Manhunters: Fugitive Task Force, following the NY/NJ Regional Task Force of the US Marshal Service.

- In 2010, FX Network aired the television series Justified following the life of Deputy US Marshal Raylan Givens (played by Timothy Olyphant).

- In the fall of 2010, NBC launched a new drama, Chase, which follows U.S. Marshal Annie Frost.[30]

- In 2011, Adult Swim aired the satirical television series Eagleheart, following cases on US Marshals Chris Monsanto (Chris Elliott), Susie Wagner (Maria Thayer), and Brett Mobley (Brett Gelman), and parodies many cop shows, most notably Walker, Texas Ranger.

- Since March 6, 2011 A&E Network has aired Breakout Kings, a drama television series revolving around a task force of convicted criminals and U.S. marshals working together in order to try and catch fugitives escaped from prison. The story is that the cons' sentences are reduced by one month for each fugitive they bring in; however if any of them should try to escape, they will all be returned to their original prisons and their sentences will be doubled.

Film

- In 1968, Clint Eastwood starred in Hang 'Em High as Deputy Marshal Jed Cooper.

- In 1973, John Wayne starred in Cahill U.S. Marshal.

- In 1977, Lee Van Cleef starred in Nowhere to Hide as Deputy Marshal Ike Scanlon.

- The 1981 film Halloween II has a marshal who assumed the duty of escorting protagonist Samuel Loomis back to the Smith's Grove Sanitarium. The marshal was later killed by Michael Myers.

- The 1993 film The Fugitive, and its 1998 spinoff U.S. Marshals, follow the operations of a fictional unit of U.S. Marshals, led by Tommy Lee Jones as Deputy United States Marshal Samuel Gerard.

- In the 1996 film Eraser, Arnold Schwarzenegger plays US Marshal John Kruger who protect a witness.

- In the 1997 film Con Air, John Cusack plays US Marshal Vince Larkin.

- In the The Spanish Prisoner, a 1997 American suspense film, the climax involves rescue of the film's hero by a team of U.S. marshals. Contrary to their depiction in the film, the United States Marshals Service would not investigate the crime depicted, theft of intellectual property, which in the United States would be treated as a state offense.[31]

- In the 1998 US Marshals (film) Tommy Lee Jones stars as a Chief Deputy Marshal Sam Gerard tasked with hunting an escaped fugitive.

- In the 1999 film Wild Wild West, Will Smith plays U.S. Marshal Jim West and Kevin Kline plays Artemus Gordon, a marshal known for his crazy inventions, who are after a fugitive named Dr. Loveless.

- The 2009 film Whiteout starred Kate Beckinsale as Deputy US Marshal Carrie Stetko.

- The 2010 movie, True Grit, follows fictional Deputy US Marshal Rooster Cogburn, played by Jeff Bridges, as he tracks down a fugitive; it is a remake of a 1969 movie of the same name, with Rooster Cogburn being played by John Wayne.

- In the 2010 movie Shutter Island, Teddy Daniels (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his partner Chuck Aule (Mark Ruffalo) are U.S marshals searching for a missing escapee from a psychiatric facility on an island off the coast of Massachusetts.

- The Virgil Cole novel Appaloosa, by Robert B. Parker, was made into a movie starring Ed Harris and Viggo Mortensen.

Video games

The video game Prey 2, published by Bethesda Softworks, features a U.S. marshal named Kilian Samuels who is one of the victims of alien abduction portrayed in the 2006 game Prey. Set several years after the first game, he works as a bounty hunter, apprehending interstellar fugitives of varying species just as he did on Earth as a marshal.

Many U.S marshals appear in the 2010 video game Red Dead Redemption. They will pursue the playable character if he gains a large enough bounty.

See also

References

- ^ United States Code, Title 28, Chapter 37

- ^ "Fact Sheet: United States Marshals Service" (PDF). usmarshals.gov. Retrieved 2011-06-17.

- ^ "United States Marshals Service – Executive Management". Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ a b "Records of the United States Marshals Service". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved June 9, 2010. "Fact Sheets: General Information". usmarshals.gov. Retrieved 2010-06-26.

- ^ "U.S. Marshals Service, History, Oldest Federal Law Enforcement Agency". Usmarshals.gov. 2004-06-03. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ^ "Marshals Service Organizational Chart". United States Department of Justice. August 13, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "History in Custody: The U.S. Marshals Service Takes Possession of North Carolina's Copy of the Bill of Rights". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Marshals make legal presence in Antarctica". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved January 8, 2007.

- ^ "U.S. Marshals Service, 2013 Facts and Figures" (PDF). U.S. Marshals Service. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ "28 USC Chapter 37 § 564". Legal Information Institute. Cornell University. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Position classification standard for United States marshal series, GS-0082" (PDF). United States Office of Personnel Management. June 1973.

- ^ "Position Classification Standard for General Investigating/Criminal Investigating Series, GS-1810/1811" (PDF). United States Office of Personnel Management.[dead link]

- ^ 28 CFR 0.112 - Special deputation. | Title 28 - Judicial Administration | Code of Federal Regulations | LII / Legal Information Institute. Law.cornell.edu. Retrieved on 2013-10-30.

- ^ "Court Security Officer position requirements". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Marshals Service for Students: A Week in the Life of a Deputy U.S. Marshal: Wednesday". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ "Marshal Robert Forsyth". Officer Down Memorial Page. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Constable Darius Quimby". Officer Down Memorial Page. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Gross, Doug (March 26, 2009). "Wanted U.S. marshal's body found in Mexico". CNN. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Robinson, Mike (April 13, 2009). "Deputy US Marshal John T. Ambrose To Be Tried For Leaking Secrets To The Mob". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Korecki, Natasha (April 28, 2009). "Deputy U.S. Marshal Ambrose guilty on two charges". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Trials". Chicago Tribune.[dead link]

- ^ "Ramaea7.com". Web.archive.org. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ^ a b "Congress Against Racism and Corruption in Law Enforcement".

- ^ "Matthew F. Fogg". Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Audit of the United States Marshals Service's Oversight of its Judicial Facilities Security Program" (PDF). United States Department of Justice. November 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "Current U.S. Marshals 15 Most Wanted Fugitives". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ ATF Online – Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms

- ^ "Current U.S. Marshals Service Major Case Fugitives". United States Marshals Service. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Obtained from Mr. Arness' official website

- ^ "''Chase'' at". Nbc.com. 2014-02-28. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ^ "Brian Beckwith, Deputy Director, United States Marshals Service, The Kojo Nnamdi Show, WAMU, Washington, DC, December 6, 2007". Wamu.org. 2007-12-06. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

External links

- Court Security Program – includes role in CSOs

- Authority of FBI agents, serving as special deputy United States marshals, to pursue non-federal fugitives

- Deputization of Members of Congress as special deputy U.S. marshals

- USC on the U.S. Marshals Service

- Retired US Marshals Association

- U.S. Diplomatic Security Service (DSS)

- Stacia Hylton Director of U.S. Marshals Service