Urusei Yatsura

| Urusei Yatsura | |

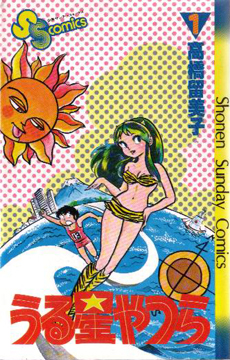

Cover art of the 1980 first tankōbon volume featuring lead characters Ataru Moroboshi and Lum Invader | |

| うる星やつら | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Teen comedy, Romance, Science fiction |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Rumiko Takahashi |

| Published by | Shogakukan |

| English publisher | Viz Media |

| Magazine | Weekly Shōnen Sunday |

| Demographic | Shōnen |

| Original run | 1978 – 1987 |

| Volumes | 34 |

| Anime television series | |

| Directed by | Mamoru Oshii (1-106) Kazuo Yamazaki (107-195) |

| Written by | Takao Koyama (1-54) Kazunori Ito (55-106) Michiru Shimada (107-195) |

| Music by | Fumitaka Anzai Katsu Hoshi Shinsuke Kazato |

| Studio | Studio Pierrot (1-106) Studio Deen (107-195) |

| Licensed by | |

| Original network | FNS (Fuji TV) |

| English network | |

| Original run | October 14, 1981 – March 19, 1986 |

| Episodes | 195 |

| See also | |

Urusei Yatsura (うる星やつら) is a comedic manga series written and illustrated by Rumiko Takahashi and serialized in Weekly Shōnen Sunday from 1978 to 1987. Its 374 individual chapters were published in 34 tankōbon volumes. It is the story of Ataru Moroboshi, and the alien Lum, who believes she is Ataru's wife after he accidentally proposes to her. The series makes heavy use of Japanese mythology, culture and puns. The series was adapted into an anime TV series produced by Kitty Films and broadcast on Fuji Television affiliates from 1981 to 1986 with 195 episodes. Eleven OVAs and six theatrical movies followed, and the series was released on VHS, Laserdisc, DVD, and Blu-ray Disc in Japan.

The manga series was republished in different formats in Japan. Viz Media licensed the series for English publication in North America under the names Lum and The Return of Lum, but dropped the series after nine volumes were released. The television series, OVAs, and five of the films were released in North America with English subtitles, as well as a dub for the films by AnimEigo. They provided extensive notes on the series to allow people to understand the many cultural references and jokes in the series that would not normally be understood by non-Japanese. The remaining film, Beautiful Dreamer, was released bilingually by Central Park Media. Five of the movies, as well as the OVA's, are available from MVM Films in the United Kingdom. The series was released on television in Southeast Asia as Lamu the Invader Girl.

The series received positive reception in and out of Japan from fans and critics alike. In 1981, the series received the Shogakukan Manga Award. The television series is credited with introducing the format of using pop songs as opening and closing themes in anime. In 2008, the first new episode in 17 years was shown at the Rumiko Takahashi exhibition It's a Rumic World.

Plot

An alien race known as the Oni arrive on Earth to invade the planet. Instead of taking over the planet by force, the Oni give humans a chance to fight for the rights to the planet by taking part in a competition. The competition is a variant of the game of tag (literally "the game of the Oni" in Japanese), in which the human player must touch the horns on the head of the Oni player within one week. The computer selected human player is Ataru Moroboshi, a lecherous, unlucky and stupid high school student from the Japanese city of Tomobiki, and the Oni player is Princess Lum, daughter of the leader of the Invasion force.

Despite his initial reluctance to take part in the competition, Ataru becomes interested in the game when he meets Lum. When the competition begins, Lum surprises everyone by flying away and Ataru finds himself unable to catch her. Before the last day of the competition, Ataru's girlfriend Shinobu Miyake encourages Ataru by pledging to marry him if he wins. On the final day of the competition, Ataru wins the game by stealing Lum's bikini top, which prevents her from protecting her horns in favor of protecting her modesty. In celebrating his victory, Ataru expresses his joy at being able to get married; however, Lum misinterprets this as a proposal from Ataru and accepts on live television. Despite the misunderstanding, Lum falls in love with Ataru and moves into his house.

Despite Ataru's lack of interest in Lum and attempts to rekindle his relationship with Shinobu, Lum frequently interferes and Shinobu loses interest in Ataru. Still, Ataru's flirtatious nature persists despite Lum's attention. Lum attempts to stop him from flirting, which results in Ataru receiving powerful electric shock attacks from Lum as punishment. Two characteristics of Ataru are particularly strong: his pervertedness and his bad luck that draws to him all weirdos of the planet, the spirit world and even galaxy.

Later Lum begins attending the same school as Ataru despite his objections. Lum develops a fan base of admirers among the boys of the school, including Shutaro Mendou, the rich and handsome heir to a large corporation that all the girls from Tomobiki have a crush on. Despite their romantic interest, none of Lum's admirers will risk upsetting Lum by trying to force her and Ataru apart, although this doesn't stop them from trying to get Ataru punished due to his bad behavior, and interfering every time they get close to him.

Production

In 1977, Rumiko Takahashi created the short story Those Selfish Aliens that was nominated for Shogakukan's Best New Comic Artist award. This would serve as the basis for creating Urusei Yatsura which was first published a year later when Takahashi was 21 years old. The series was her first major work, having previously only published short stories and is a combination of romantic comedy, science fiction, suburban life, and Japanese folktales.[1][2] The title of the series roughly translates to "Those Obnoxious Aliens". The title is written using specific kanji instead of hiragana to create a Japanese pun.[3]

The series first appeared in Shogakukan's Weekly Shonen Sunday in September 1978.[4] At the start of the series it was only scheduled to run for 5 chapters. Ataru was the central character and each chapter would feature a different strange character. The character of Lum was only going to appear for the first chapter and was not in the second chapter, however Takahashi decided to re-include her in the third chapter.[5] The series was not an instant success and chapters were initially published sporadically. Between May and September 1978 she simultaneously worked on a series called Dust Spot, however the increasing popularity of Urusei Yatsura caused her to focus on Urusei and the series became a regular serialization from the middle of 1979.[4]

Takahashi said that she had been dreaming about the overall universe of Urusei Yatsura since she was very young. She said that the series "really includes everything I ever wanted to do. I love science fiction because sci-fi has tremendous flexibility. I adopted the science fiction-style for the series because then I could write any way I wanted to".[1] She wanted the reader to be completely surprised by the next panel and used slapstick comedy to create a reaction in the reader.[4] When Takahashi ran out of ideas she would create new characters.[6] Takahashi shared a small 150 square feet apartment with her assistants, and slept in a closet due to a lack of space. While writing Urusei Yatsura she also began work on Maison Ikkoku and used this experience as well as her university experience as the basis for the setting of that series.[4]

Character names often carry extra meanings used to describe a characters personality or other traits. For example, the name Ataru Moroboshi refers to being hit by a star, a reference to the aliens and other people who gather around him. The name Shinobu suggests a patient character, however this in contrast to the character's actual personality.[3] In a similar way, the setting for the series is "Tomobiki", which means "friend taking". Tomobiki is also the name of a superstitious day in the old Japanese calendar system considered to have "no winners or losers" and occurred on every sixth day. Funerals rarely took place on this day as it was believed more deaths would soon follow.[3][7][8] Lum was named after Agnes Lum, a bikini model during the 1970s. Lum's use of the English word "Darling" in reference to Ataru was to emphasize her status as a foreigner.[9][10]

In 1994, Takahashi stated that she will not produce any more content for the series.[11]

The characters of Megane, Perm, Kakugari and Chibi are recurring characters throughout the anime adaptation, however in the manga they are nameless fans of Lum who are never seen after Mendou is introduced.[12] In contrast the character Kosuke Shirai plays a large role in the manga, but does not appear in the anime series. His role is often performed by Perm.[13] The second half of the anime is closer to the manga than the first half.[12]

Media

Manga

The series began sporadic serialization in September 1978 in that year’s 39th issue of the manga anthology Weekly Shōnen Sunday until the middle of 1979 when it became a regular serialisation.[4][14] It ended in 1987's eighth issue after publishing 374 chapters and almost 6000 pages.[12][15][16] A total of 34 individual volumes with 11 chapters each were released in tankōbon format between 1980 and March 1987.[16][17][18] After the tenth anniversary of start of the series, it was printed in 15 "wideban" editions between July 1989 and August 1990.[19][20] Each volume contained around 25 chapters, and were printed on higher quality paper, with new inserts.[16] A bunkoban edition of the series was released over 17 volumes between August 1998 and December 1999. Each volume contains forewords by other manga creators discussing the influence the series had on them.[16][21][22] A "My First Big" edition was printed between July 2000 and September 2004. This edition was similar to the tankōbon but used low quality paper and were sold at a low price.[16][23][24] A shinsoban edition over 34 volumes was released between November 17, 2006 and March 18, 2008. This edition was also similar to the tankōbon but used new cover artwork and included a section that displayed artwork from current manga artists.[16][25][26]

The manga has sold over 26 million copies in Japan.[27]

After requests from fans, Viz Media licensed the series for release in English across North America under the title of Lum * Urusei Yatsura.[28] Despite a strong start, the series was dropped after 8 issues. The series was then reintroduced in the monthly Viz publication Animerica and because of the long gap the series was retitled The Return of Lum.[16] To start chapters were published monthly in Animerica, however due to reader feedback and an increased popularity of the series it was decided to release it as an individual monthly publication.[29] The English release finished in 1998 and is now out of print. The first 11 volumes of the Japanese release were covered, but several chapters were excluded and a total 9 English volumes of the series were released.[12][16]

Anime

The series was adapted by Kitty Films into an animated TV series that aired from October 14, 1981 to March 19, 1986 on Fuji Television.[30] Initial episodes of the series contained two stories which has led to episode totals of both 195 and 218 episodes.[31] Episode 10 was the first episode to only contain one story.[32] The first 106 episodes were directed by Mamoru Oshii and the remainder by Kazuo Yamazaki.[33][34] Six opening theme songs and nine closing themes were used during the series.[35]

On December 10, 1983, the first VHS release of the series was made available in Japan.[36] The series was also released on fifty Laserdiscs.[37] Another VHS release across fifty cassettes began on March 17, 1998 and concluded on April 19, 2000.[38][39] Two DVD boxed sets of the series were released between December 8, 2000 and March 9, 2001.[40][41] These were followed by fifty individual volumes between August 24, 2001 and August 23, 2002.[42][43] To celebrate the 35th anniversary of the anime a new HD transfer was created and released on Blu-ray in Japan. The first Blu-ray boxed set of the series was released on March 27, 2013, with the fourth box set scheduled for release on March 23, 2014.[30][44]

During 1992, the series was licensed for a North American release by AnimEigo. Their VHS release began in October of the same year and was among the first anime titles to receive a subtitled North American release. However the release schedule was erratic.[12][28][45] The first two episodes were released with an English dub on March 29, 1995 as Those Obnoxious Aliens.[46] Anime Projects released the series in the United Kingdom from April 25, 1994.[47] AnimEigo later released the series on DVD. The series was available in box set format as well as individual releases. A total of 10 boxed sets and 50 individual DVDs were released between March 27, 2001 and June 20, 2006.[48][49] Each DVD and VHS contained Liner notes explaining the cultural references and puns from the series.[50] A fan group known as "Lum's Stormtroopers" convinced the Californian public television station KTEH to broadcast subtitled episodes of the series in 1998.[28] AnimeEigo's license later expired, and has confirmed that the series is out of print as of September 2011.[51] An improvisational dub of the first two episodes was broadcast on BBC Choice in 2000 as part of a "Japan Night" special as "Lum the Invader Girl".[2][52]

The anime was distributed in Southeast Asia on Animax Asia as Lamu the Invader Girl.[53]

Films

During the Television run of the series, four theatrical films were produced. Urusei Yatsura: Only You was directed by Mamoru Oshii and began showing in Japanese cinemas on February 11, 1983.[54] Urusei Yatsura 2: Beautiful Dreamer was directed by Mamoru Oshii and was released on February 11, 1984.[55] Urusei Yatsura 3: Remember My Love was directed by Kazuo Yamazaki and released on January 26, 1985.[56] Urusei Yatsura 4: Lum the Forever was directed again by Kazuo Yamazaki and released on February 22, 1986.[57]

After the conclusion of the television series, two more films were produced. A year after the television series finished, Urusei Yatsura: The Final Chapter was directed by Satoshi Dezaki and was released on February 6, 1988 as a tenth anniversary celebration. It was shown as a double bill with a Maison Ikkoku movie.[37][58] The final film, Urusei Yatsura: Always My Darling was directed by Katsuhisa Yamada and was released on August 18, 1991.[59][60] In North America, "Beautiful Dreamer" was released by Central Park Media. The remaining five films were released by AnimEigo in North America and MVM Films in the United Kingdom.[50]

OVA releases

On September 24, 1985, the special Ryoko's September Tea Party was released consisting of a mixture of previously broadcast footage with 15 minutes of new material. A year later on September 15, 1986, Memorial Album was released, mixing new and old footage.[50][61] On July 18, 1987 the TV special Inaba the Dreammaker was broadcast before being released to video. It was followed by Raging Sherbet on December 2, 1988, and by Nagisa's Fiancé four days later on December 8, 1988. The Electric Household Guard was released on August 21, 1989 and followed by I Howl at the Moon on September 1, 1989. They were followed by Goat and Cheese on December 21, 1989 and Catch the Heart on December 27, 1989. Finally Terror of Girly-Eyes Measles and Date with a Spirit were released on June 21, 1991.[62] The OVA's were released in North America by AnimEigo who released them individually over 6 discs.[50] In the UK they were released as a 3 disc collection by MVM on September 6, 2004.[63]

On December 23, 2008 a special was shown at the It's a Rumic World exhibition of Rumiko Takahashi's works. Entitled The Obstacle Course Swim Meet, it was the first animated content for the series in 17 years.[64] On January 29, 2010 a boxed set was released featuring all of the recent Rumiko Takahashi specials from the Rumic World exhibition. Entitled It's a Rumic World, the boxed set contains The Obstacle Course Swim as well as a figure of Lum.[65]

Other media

A large number of LP albums were released after the series began broadcasting. The first soundtrack album was Music Capsule which was released on April 21, 1982, and a follow-up Music Capsule 2 was released on September 21, 1983. A compilation The Hit Parade was released in July 1983, and The Hit Parade 2 was released on May 25, 1985. A cover album by Yuko Matsutani, Yuko Matsutani Songbook was released on May 21, 1984. Lum's voice actress Fumi Hirano also released a cover album, Fumi no Lum Song which was released on September 21, 1985.[66][67]

Many games have been produced based on the series.[68] The first game to be released was a handheld electronic game, released by Bandai in 1982. Following it were microcomputer games, as well as Urusei Yatsura: Lum no Wedding Bell (うる星やつらラムのウェディングベル), which was released by Jaleco for the Famicom on October 23, 1986, exclusively in Japan.[69] The latter was developed by Tose as a port of the unrelated arcade game Momoko 120%.[70] In 1987, Urusei Yatsura was released by Micro Cabin for the Fujitsu FM-7 and Urusei Yatsura: Koi no Survival Party (うる星やつら恋のサバイバルパーチー) was released for the MSX computer.[71][72] Urusei Yatsura: Stay With You (うる星やつら Stay With You) was released by Hudson Soft for the PC Engine CD on June 29, 1990 with an optional music CD available.[73] Urusei Yatsura: Miss Tomobiki o Sagase! (うる星やつらミス友引を探せ!) was released by Yanoman for the Nintendo Game Boy on July 3, 1992.[74] Urusei Yatsura: My Dear Friends (うる星やつら~ディア マイ フレンズ) was released by Game Arts for the Sega Mega-CD on April 15, 1994.[75] Urusei Yatsura: Endless Summer (うる星やつら エンドレスサマー) was released for the Nintendo DS by Marvelous on October 20, 2005.[76]

Reception

Takahashi stated that the majority of Japanese Urusei Yatsura fans were high school and university students. The series' peak readership figures were with 15-year-olds, but the distribution of readers was skewed towards older males. She said that this was "very easy" for her since the ages of the readers were similar to her own age; Takahashi expressed happiness that people from her generation enjoy the series. Takahashi added that she felt disappointment that Urusei Yatsura did not gain much interest from children, believing that the series may have been too difficult for children. She believed that "manga belongs fundamentally to children, and maybe Urusei Yatsura just didn't have what it took to entertain them".[1]

The manga received the Shogakukan Manga Award in 1981.[77]

In Manga: The Complete Guide, Jason Thompson referred to the original manga as "A slapstick combination of Sci-Fi, fairy-tale and ghost-story elements with plenty of cute girls". He also notes that Lum is "the original Otaku dream girl". He awarded the series four stars out of four.[78] Christina Carpenter of THEM Anime praises the characters and humor and notes the influence the series had on other series over the years. Carpenter summarises the series as "Original and unapologetically Japanese classic that earns every star we can give" and awarded the series five stars out of five.[79] In an interview with Ex.org, Fred Schodt expressed a surprise at the popularity of the English release of the manga as he believed the cultural differences would be a problem.[80]

In 1982, the anime series is ranked sixth in Animage's the "Anime Grand Prix".[81] The following year, the show climbed to fourth place.[82] In 1984, the OVA Urusei Yatsura: Only You took fifth and the anime took sixth.[83] While the series did not appear in 1985, the movie Beautiful Dreamer did. In 1986, the show reappeared in sixth place and third OVA took third place.[84] In 1987, the series went down to eighth place.[85] The series received two awards from the magazine Animage as part of their reader-voted Anime Grand Prix. In 1982, the theme song "Lum no Love Song" was voted best anime song. In 1983, the sixty-seventh episode was voted best episode.[86][87]

In The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917, Jonathan Clements and Helen McCarthy viewed the series as "a Japanese Simpsons for its usage of domestic humor and make note of AnimEigo's attention to providing notes for those unfamiliar with Japanese culture. They summarise the series as "a delight from beginning to end" and that the series "absolutely deserves its fan favorite status".[2] In a feature of the series in Anime Invasion McCarthy recommends the series as being "the first, the freshest and the funniest" of Takahashi's works and also for the large cast, stories and as a cultural and historical resource.[88] Writing in Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation, Susan J. Napier dedicates several pages to discussion of the series, regarding it as "a pioneering work in the magical girlfriend genre". Napier contrasts the series to Western shows such as Bewitched and I Dream of Jeannie, highlighting their harmonious resolution to the chaos in comparison to Urusei Yatsura's "out of control" ending to each episode. Napier later compares the series to other magical girlfriend series such as Ah! My Goddess and Video Girl Ai.[89] Fred Patten writing in Watching anime, reading manga: 25 years of essays and reviews credits the series with being the first program to inspire translations from fans.[90] Patten later credits the series for introducing the phenomenon of using anime to advertise pop songs, claiming it was a deliberate decision by Kitty Films.[91] Writing further about the series for website Cartoon Research, Patten notes that the series was aimed at adults who could buy their own merchandise, as opposed to being subsidised by toy sales like many other shows at the time.[31] Like Napier, Patten compares the series to Bewitched, but also to Sabrina the Teenage Witch.[92]

Influence and legacy

The series has been credited by Jonathan Clements in Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade as influencing multiple other "geek gets girl" works including Tenchi Muyo and Love Hina.[93] Tokyo Movie Shinsha produced the series Galaxy High School for CBS as an attempt to create a similar series for the American market. The school scenario is reversed to be based around humans attending a high school for aliens.[31]

In 1992, the singer Matthew Sweet released the single "I've been waiting", the video of which features images of Lum from the series.[94] In 1993, a band from Glasgow formed under the name "Urusei Yatsura" as a tribute.[95] On Star Trek: The Next Generation anime references were frequently added as in-jokes and homages by Senior Illustrator Rick Sternbach. In the episode Up the Long Ladder, two ships named Urusei Yatsura and Tomobiki can be seen on a graphical display.[96][97]

Use of Japanese culture

The series is considered an excellent source for references to Japanese culture and mythology.[98] The series makes heavy use of Japanese literature, folklore, history and pop culture. Examples of literature and folklore include The Tale of Genji and Urashima Tarō.[99]

Many of the characters in the series are derived from mythological creatures. In some cases the creatures themselves appeared, and in other cases a character was designed to incorporate the characteristics of a mythological creature.[100] Stories and situations made use of these mythological elements to create jokes and draw comparisons with the original mythology. For example, the Oni choose tag to decide their contest with Earth because the Japanese word for Tag, Onigokko, means "game of the Oni". When Ataru grabs Lum's horns during their contest and she misunderstands his statement that he can get married, it is a reference to the myth that grabbing the horns of an Oni will make your dream come true.[3]

References

- ^ a b c Horibuchi, Seiji; Jones, Gerard; Ledoux, Trish. "The Wacky World of Rumiko Takahashi". Animerica. 1 (2): 4–11.

- ^ a b c Clements, Jonathan; McCarthy, Helen (2006). The Anime Encyclopedia: A Guide to Japanese Animation Since 1917 (Revised and Expanded edition). p. 377. ISBN 1-933330-10-4.

- ^ a b c d "Urusei Yatsura volumes 1-10 Liner Notes". AnimEigo. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Manga Mania" (20). Manga Publishing. December 1994: 38–41. ISSN 0968-9575.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "「るーみっくわーるど35~SHOWTIME&ALL-STAR~高橋留美子画業35周年インタービュー (3/5)". Comic Natalie. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Toren. "Toriyama/Takahashi interview". Furinkan.com. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ De Garis, Frederic. We Japanese. Routledge. p. 292. ISBN 9781136183676.

- ^ De Garis, Frederic. We Japanese. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 9781136183676.

- ^ "「るーみっくわーるど35~SHOWTIME&ALL-STAR~高橋留美子画業35周年インタービュー (4/5)". Comic Natalie. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. p. 89. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- ^ Karvonen, K.J. "A Talk With Takahashi". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Frequently asked Questions". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Other Characters". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら サンデー名作ミュージアム". Shogakukan. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Career Timeline". Furinkan. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Manga". Furinkan.com. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつら (1) (少年サンデーコミックス) (新書)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら 34 (少年サンデーコミックス) (単行本)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら (1) (少年サンデーコミックス〈ワイド版〉) (新書)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら (15) (少年サンデーコミックス〈ワイド版〉) (-)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら (1) (小学館文庫) (文庫)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら (17) (小学館文庫) (文庫)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら/大勝負 (My First Big) (単行本)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "る星やつら/失われたモノを求めて (My First Big) (ムック)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら 1 新装版 (少年サンデーコミックス) (コミック)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら 34 新装版 (少年サンデーコミックス) (コミック)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら (原作)". Shogakukan-Shueisha Productions. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c Huddlestone, Daniel (1999). "Spotlight — Urusei Yatsura". Animerica. 7 (4): 13–15, 31–33.

- ^ Ledoux, trish (July 1994). "Animerica". 2 (7). Viz Media: 2. ISSN 1067-0831.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "TVアニメーション うる星やつら Blu-ray BOX.1". Warner Home Video. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ a b c Patten, Fred (September 15, 2013). "The "Teenagers From Outer Space" Genre". Cartoon Research. Retrieved May 28, 2014.

- ^ "A Very Anime Christmas". Anime News Network. December 19, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Episodes 44-54". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Episodes 107-127". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Hit Parade". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら(1) [VHS]". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ a b "About the Anime". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "うる星やつら(1)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつら(50)". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつら TVシリーズ 完全収録版 DVD-BOX1". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつら TVシリーズ 完全収録版 DVD-BOX2". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつらDVD vol.1". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "うる星やつらDVD Vol.50". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

- ^ "TVアニメーション うる星やつら Blu-ray BOX.4". Warner Home Video. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Anime News Dateline". Animerica. 1 (0): 6. 1992.

- ^ "Animerica". 3 (3). Viz Media: 15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Anime UK". 3 (2). April 1994: 31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Urusei Yatsura, TV Series 1 (Episodes 1-4) (1982)". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura TV, Vol. 50". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Urusei Yatsura". AnimEigo. Archived from the original on February 2, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "AnimEigo's Urusei Yatsura License Expires in September". Anime News Network. February 9, 2011. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^ "Tokyo Calling". The Guardian. August 4, 2000. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "ANIMAX Southeast Asia June 2006" (Archive). Animax Asia. 25 April 2006. Retrieved on 8 June 2015.

- ^ "Only You". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Steadman, J.M. "Beautiful Dreamer". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Steadman, J.M. "Remember My Love". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Steadman, J.M. "Lum the Forever". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Steadman, J.M. "The Final Chapter". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ うる星やつら いつだってマイ・ダーリン (in Japanese). madhouse.co.jp. Retrieved 2011-07-31.

- ^ Steadman, J.M. "Always my Darling". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Animage Pocket Data Notes 1999. Tokyo, Japan: Tokuma Shoten. March 1999. p. 69.

- ^ "OVA's". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Ova Collection [DVD]". Amazon UK. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ "Event-Only Urusei Yatsura Anime to Debut This Month (Updated)". Anime News Network. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "It's a Rumic World スペシャルアニメBOX". Amazon.co.jp. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura Albums from 1982 to 1984". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura Albums from 1985 to 1986". Furinkan.com. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura". UVL. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Lum no Wedding Bell". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Lum no Wedding Bell arcade origins". UVL. Retrieved July 17, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Stay With You". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Miss Tomobiki o Sagase!". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: My Dear Friends". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura: Endless Summer". GameFAQs. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ 小学館漫画賞:歴代受賞者 (in Japanese). Shogakukan. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- ^ Thompson, Jason (October 9, 2007). Manga: The Complete Guide. New York, New York: Del Rey. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8. OCLC 85833345.

- ^ Carpenter, Christina. "Urusei Yatsura". THEM Anime. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ McCarter, Charles; Kime, Chad. "An Interview with Fred Schodt (continued)". Ex.org. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ "第4回アニメグランプリ [1982年6月号] ( June 1982 - 4th Anime Grand Prix)". Animage. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "第5回アニメグランプリ [1983年6月号] ([June 1983] 5th Anime Grand Prix)". Animage. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "第6回アニメグランプリ [1984年6月号] ( [June 1984] 6th Anime Grand Prix)". Animage. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "第8回アニメグランプリ [1986年6月号] ([June 1986] 8th Anime Grand Prix)". Animage. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "第9回アニメグランプリ [1987年6月号] ([June 1987] The 9th Anime Grand Prix)". Animage. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "第4回アニメグランプリ[1982年6月号]". Tokuma Shoten. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ "第5回アニメグランプリ[1983年6月号]". Tokuma Shoten. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ^ McCarthy, Helen (Spring 2002). "Anime Invasion" (2). Wizard Entertainment: 58–59. ISSN 1097-8143.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Napier, Susan J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. pp. 142–153. ISBN 0-312-23863-0.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. p. 47. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. p. 94. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. p. 243. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- ^ Jonathan Clements (2009). Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade. Titan Books. p. 326. ISBN 978-1848560833.

- ^ Patten, Fred (2004). Watching Anime, Reading Manga: 25 Years of Essays and Reviews. Stone Bridge Press. p. 41. ISBN 1-880656-92-2.

- ^ "Urusei Yatsura Biography, Page 1". UruseiYatsura.co.uk. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

- ^ Nemeck, Larry (1995). Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion (Revised). Simon & Schuster. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-671-88340-2.

- ^ Nemeck, Larry (1995). Star Trek: The Next Generation Companion (Revised). Simon & Schuster. p. 88. ISBN 0-671-88340-2.

- ^ Poitras, Gilles (February 1, 2006). "Mentions of Me". Retrieved December 18, 2007.

- ^ Camp, Brian; Davis, Julie. Anime Classics Zettai!. pp. 376–380. ISBN 978-1-933330-22-8.

- ^ West, Mark I. The Japanification of Children's Popular Culture: From Godzilla to Miyazaki. Scarecrow Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0810851214.

External links

- AnimEigo - United States distributor of the Urusei Yatsura anime.

- Lam, the Invader Girl

- Urusei Yatsura Template:Ja icon

- Furinkan.com

- The World of Urusei Yatsura's Lum

- Urusei Yatsura (anime) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Manga series

- 1978 manga

- 1981 anime television series debuts

- Urusei Yatsura

- 1981 anime television series

- 1985 anime OVAs

- 1986 Japanese television series endings

- 1987 comics endings

- Alien invasions in comics

- Anime series based on manga

- Comedy anime and manga

- Fuji Television shows

- Harem anime and manga

- Japanese mythology in anime and manga

- Pierrot (company)

- Science fiction anime and manga

- Sharp Point Press titles

- Shogakukan manga

- Shōnen manga

- Studio Deen

- Teen comedy comics

- Viz Media manga

- Winners of the Shogakukan Manga Award for shōnen manga

- Works by Rumiko Takahashi