User:Sjanusz/PT

Philosophical Transactions later Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (Phil. Trans.) is a scientific journal published by the Royal Society. It was established in 1665,[1] making it the first journal in the world exclusively devoted to science. It is also the world's longest-running scientific journal. The slightly earlier Journal des sçavans published some science (about a third of its material, compared to Phil Trans 85%), also containing subject matter from other fields of learning, and its main content type was book reviews (86%; Phil. Trans. contained proportionally far fewer at 18%).[2][3][4] The use of the word "Philosophical" in the title refers to "natural philosophy", which was the equivalent of what would now be generically called "science". "Transactions" meanwhile was often applied to ephemeral literature including newsbooks - early newspapers - and refers to the dealings or doings, often of groups of individuals including parliament, as well as transitory committees within organisations.[5]

Current publication[edit]

In 1887 the journal expanded and divided into two separate publications, one serving the Physical Sciences (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Physical, Mathematical and Engineering Sciences) and the other focusing on the life sciences (Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences). Both journals now publish themed issues and issues resulting from papers presented at the Discussion Meetings of the Royal Society. Primary research articles are published in the sister journals Proceedings of the Royal Society, Biology Letters, Journal of the Royal Society Interface, and Interface Focus.

Origins and Early History[edit]

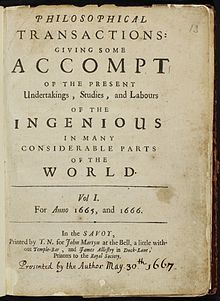

The first issue, published 6 March 1665, was edited and published by the Society's first secretary, Henry Oldenburg, four-and-a-half years after the Royal Society was founded.[6] Its full title of the journal as given by Oldenburg, "Philosophical Transactions, Giving some Accompt to the of the present Undertakings, Studies, and Labours of the Ingenious in many considerable parts of the World". The Society's Council minutes dated 1 March 1664 (in the Julian calendar, equivalent to 1665 in the modern Gregorian system) ordered that "the Philosophical Transactions, to be composed by Mr Oldenburg, be printed the first Munday of every month, if he have sufficient matter for it, and that that tract be licensed by the Council of this Society, being first revised by some Members of the same". Oldenburg published the journal at his own personal expense and seems to have entered into an agreement with the Society's Council allowing him to keep any resulting profits. He was to be disappointed, however, since the journal performed poorly from a financial point of view during his lifetime, just about covering the rent on his house in Piccadilly.[7]

The familiar functions of the scientific journal – Registration (date stamping and provenance), Certification (peer review), Dissemination and Archiving − were introduced at inception by Philosophical Transactions. The beginnings of these ideas can be traced in a series of letters from Oldenburg to Robert Boyle:[8]

- [24/11/1664] We must be very careful as well of regist'ring the person and time of any new matter, as the matter itselfe, whereby the honor of the invention will be reliably preserved to all posterity' (registration and archiving)

- [03/12/1664] '...all ingenious men will thereby be incouraged to impact their knowledge and discoverys' (dissemination)

- The Council minute of 1 March 1665 made provisions for the tract to be revised by members of the Council of the Royal Society, providing the framework for peer review to eventually develop, becoming fully systematic as a process by the 1830s.

The printed journal replaced much of Oldenburg's letter-writing to correspondents, at least on scientific matters, and as such can be seen as a labour-saving device. Oldenburg also described his journal as "one of these philosophical commonplace books", indicating his intention to produce a collective notebook between scientists.[9]

Issue 1 contained such articles as: an account of the improvement of optic glasses; the first report on the Great Red Spot of Jupiter; a prediction on the motion of a recent comet (probably an Oort cloud object); a review of Robert Boyle's 'Experimental History of Cold'; Robert Boyle's own report of a deformed calf; A report of a peculiar lead-ore from Germany, and the use thereof; "Of an Hungarian Bolus, of the Same Effect with the Bolus Armenus; Of the New American Whale-Fishing about the Bermudas," and "A Narrative Concerning the Success of Pendulum-Watches at Sea for the Longitudes". The final article of the issue concerned "The Character, Lately Published beyond the Seas, of an Eminent Person, not Long Since Dead at Tholouse, Where He Was a Councellor of Parliament". The eminent person recently deceased was Pierre de Fermat, although the issue failed to mention the last theorem.[10]

Oldenburg referred to himself as the compiler and sometimes Author of the Transactions, and always claimed that the journal was entirely his sole enterprise – although with the Society's imprimatur and containing reports on experiments carried out by of many of its Fellows, many readers saw the journal as an official organ of the Society. It has been argued that Oldenburg benefitted from this ambiguity, retaining independence and the prospect of monetary gain, while simultaneously enjoying the credibility afforded by the association. Certainly the tone of the early volumes was set by Oldenburg, who often related things he was told by his contacts, translated letters and manuscripts from other languages, and reviewed books, always being sure to indicate the provenance of his material – contributing significantly to the use of citation in scholarly communications.

By reporting ongoing and often unfinished scientific work that may otherwise have not been reported, the journal had a central function of being a scientific news service. At the time of Phil. Trans. foundation, print was heavily regulated, and there was no such thing as a free press. In fact, the first English newspaper (which was still state-sanctioned, The London Gazette, did not appear until after Phil. Trans in the same year.

Oldenburg's compulsive letter writing to foreign correspondents led to him being suspected of being a spy for the Dutch and interred in the Tower of London in 1667. A rival took the opportunity to publish a Pirate issue of Philosophical Transactions, with the pretense of it being Issue 27. Oldenburg repudiated the issue by publishing the real 27 upon his release. It would not be the last time that Pirates and the journal would cross paths (see Pirate Bay Episode, below).

Upon Oldenburg's death, following a brief hiatus, the position of Editor was passed down through successive secretaries of the Society as an unofficial responsibility and at their own expense. Robert Hooke changed the name of the journal to Philosophical Collections in 1679 – a name that remained until 1682, when it changed back. The position of editor was sometimes held jointly and included William Musgrave (Nos 167 to 178) and Robert Plot (Nos 144 to 178).[11]

The Society's Takeover in the 18th Century[edit]

Following a series of biting satires in the first half of the 18th century by individuals including the well known Jonathan Swift, and the less well-known but singularly effective John Hill, an actor, writer, apothecary and failed candidate for election to the Society. His satires on the Society and 'its works', which included in this instance the Transactions (which was supposedly an independent publication), forced the Society to bring the journal's publication under its control in 1752. However, it was not until 1786 that the title "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society" was first applied.

Famous and Notable Contributors[edit]

Over the centuries, many important scientific discoveries have been published in the Philosophical Transactions. Famous contributing authors include:

| Isaac Newton | His first paper New Theory about Light and Colours,[12] (1672) can be seen as the beginning of his public scientific career. |

| Benjamin Franklin | The American statesman was the sole or co-author of 19 papers in Phil Trans, including an experiment on the calming effects of oil on water (of great significance to current scientific fields including surface chemistry and physics, and self-assembly) carried out on Clapham Common pond. But it was his "Philadelphia Experiment", A Letter of Benjamin Franklin, Esq; to Mr. Peter Collinson, F. R. S. concerning an Electrical Kite - recognized as one of the most famous scientific experiments of all time - and published in Phil. Trans in 1753, that secured his reputation. He later founded the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, closely modelled on the Royal Society. |

| William Roy | Major General William Roy measured the distance between the Greenwich and Paris observatories, using a method of triangulation and instruments designed and built by Jesse Ramsden. This work led to much more accurate records of longitudes for both the British and French - remarkable during a century of near-constant warfare between the two nations. The work was written up in three papers in Phil Trans, culminating in a 1790 publication, An Account of the Trigonometrical Operation, Whereby the Distance between the Meridians of the Royal Observatories of Greenwich and Paris Has Been Determined (with Isaac Dalby). While, like most English maps at the time, the prime meridian is centred on St Paul's cathedral (a system the vestiges of which can be found in the naming of the British road network), Roy's figure showing the triangulation of major distances between England and France takes Greenwich as the prime meridian. While this had been suggested before, notably by Edmund Halley in 1710, this was one of the first major works to take Greenwich as prime meridian, anticipating its status as the universal prime meridian. Roy's work in Phil. Trans. led to the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain. |

| Caroline Herschel | The first paper by a woman in the journal, An account of a new comet appeared in 1787.[13] Caroline Herschel was paid a salary of £50 per annum by the King to work with her brother William Herschel as an astronomer – unusual at a time when most who worked in astronomy or science did so without pay, regardless of gender |

| Mary Somerville | On the Magnetizing Power of the More Refrangible Solar Rays[14] was one of two papers submitted to Philosophical Transactionss by Scottish polymath, translator of Laplace and friend of JMW Turner. In it, she communicates her finding that the ultraviolet components of the electromagnetic spectrum could magnetise a steel needle. While subsequent experiments were not able to reproduce this finding, leading Somerville to retract her claim (exactly in accordance with what would be expected of a scientist today), her reputation was secured. In some ways, her hypothesis remarkably prescient: the photoelectric effect is more likely to occur when metals are irradiated by light at the violet end of the spectrum. |

| Charles Darwin | Darwin's only paper in Phil. Trans., the snappily titled Observations on the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy, and of Other Parts of Lochaber in Scotland, with an Attempt to Prove That They Are of Marine Origin[15] (1837) describes remarkable geological formations in the Scottish Highlands, and offers an explanation for their formation based on similar features he had seen at Coquimbo in Chile while on the Beagle. They were subsequently explained by French geologist Louis Agassiz. |

| Michael Faraday | Publishing over 40 papers in the journal, Faraday rose from a fairly humble background to become a world-famous and highly respected scientist. His final paper in the journal, which was given as the Bakerian Lecture in 1857, Experimental Relations of Gold (and Other Metals) to Light,[16] introduced the idea of metal particles that were smaller than the wavelength of light – colloidal sols or what would now be called nanoparticles. |

| James Clerk Maxwell | In On the Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field[17] (1865) Maxwell described how electricity and magnetism could travel as a wave and inferred from the velocity given by the wave equation, and by known experimental determinations of the speed of light, that light was an electromagnetic wave. |

| Kathleen Lonsdale | Lonsdale's work carried out at the Royal Institution led to 17 papers in Royal Society journals, two of which were in Phil. Trans. Like many notable figures in the 'new sciences' of structural and cell biology, and also the new physics (which included luminaries such as Paul Dirac), she published the bulk of her work in the more regular Proceedings of the Royal Society. Her 1947 paper, Divergent-Beam X-Ray Photography of Crystals,[18] built on earlier work to show how this nuanced technique could reveal information about the purity and degree of 'perfection' of a crystal. |

| Dorothy Hodgkin | Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin's record of publishing in Royal Society journals spanned 50 years, beginning in 1938. Out of 20 papers, only two were published in Phil. Trans., the first in 1940, when she was still called Dorothy Crowfoot and was working with JD Bernal. The second, in 1988, was her final publication in a Royal Society journal. Hodgkin used advanced techniques to crystallise proteins, allowing their structures to be elucidated by X-ray crystallography, including Vitamin B-12[19] and insulin[20] |

| Alan Turing | Turing's 1952 paper, On the Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis,[21] gave a chemical and physical basis for many of the patterns and forms found in nature, a year before the structure of DNA was reported by Watson and Crick. They published their initial findings in Nature and subsequently published an expanded version in Proceedings of the Royal Society A. In the paper, Turing coins the term morphogen, which is now used in the sciences of developmental biology and epigenetics, to denote a chemical species that modulates the growth of a species. |

| Stephen Hawking | A 1983 paper The Cosmological Constant[22] was actually Hawking's seventh in a Royal Society journal, but his first in Phil Trans (all the others appeared in Proceedings). The paper was first presented at a themed meeting at the Royal Society, providing a model for the journal's content that continues to this day (unlike Proceedings, which publishes new research on any scientific subject, divided along the physical and life sciences, Phil. Trans. is now always themed and roughly half of the time taken from open 'discussion' meetings at the Society's headquarters in London, which are free to attend). The meeting in this instance also featured papers given by future Astronomer Royal and President of the Royal Society, Martin Rees, then-recent Nobel Laureate Steven Weinberg, future winners of Royal Society premier medals Chris Llewellyn Smith and John Ellis, and Michael Faraday Prize winner and popular science author John D Barrow. |

Pirate Bay Episode[edit]

In July 2011 programmer Greg Maxwell released through the The Pirate Bay, the nearly 19 thousand articles that had been published before 1923, and were therefore in the public domain. They had been digitized for the Royal Society by Jstor, for a cost of less than USD100,000, and public access to them was restricted through a paywall.[23][24] In October of the same year, the Royal Society released for free all its articles prior to 1941, but denied that this decision had been influenced by Maxwell's actions. [23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Oldenburg, Henry (1665). "Epistle Dedicatory". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 1: 0–0. doi:10.1098/rstl.1665.0001.

- ^ http://asp.revues.org/213

- ^ http://erea.revues.org/1334

- ^ "Special Collections | The Dibner Library of the History of Science and Technology". Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ http://mercuriuspoliticus.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/newsbooks-1649-1650.pdf

- ^ "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London - History". Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ Bluhm, R. K. (1960). "Henry Oldenburg, F.R.S. (c. 1615-1677)". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 15: 183–126. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1960.0018.

- ^ Royal Society Archives

- ^ 'Notebooks, Virtuosi and Early-Modern Science' – Richard Yeo

- ^ http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/1/1-22.toc

- ^ A. J. Turner, ‘Plot, Robert (bap. 1640, d. 1696)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Newton, I. (1671). "A Letter of Mr. Isaac Newton, Professor of the Mathematicks in the University of Cambridge; Containing His New Theory about Light and Colors: Sent by the Author to the Publisher from Cambridge, Febr. 6. 1671/72; in Order to be Communicated to the R. Society". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 6 (69–80): 3075–3087. doi:10.1098/rstl.1671.0072.

- ^ Herschel, C. (1787). "An Account of a New Comet. In a Letter from Miss Caroline Herschel to Charles Blagden, M. D. Sec. R. S". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 77: 1. doi:10.1098/rstl.1787.0001.

- ^ Somerville, M. (1826). "On the Magnetizing Power of the More Refrangible Solar Rays". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 116: 132. doi:10.1098/rstl.1826.0014.

- ^ Darwin, C. (1839). "Observations on the Parallel Roads of Glen Roy, and of Other Parts of Lochaber in Scotland, with an Attempt to Prove That They Are of Marine Origin". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 129: 39. doi:10.1098/rstl.1839.0005.

- ^ Faraday, M. (1857). "The Bakerian Lecture: Experimental Relations of Gold (and Other Metals) to Light". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 147: 145. doi:10.1098/rstl.1857.0011.

- ^ Maxwell, J. C. (1865). "A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 155: 459. doi:10.1098/rstl.1865.0008.

- ^ Lonsdale, K. (1947). "Divergent-Beam X-Ray Photography of Crystals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 240 (817): 219. doi:10.1098/rsta.1947.0002.

- ^ Hodgkin, D. C.; Kamper, J.; Lindsey, J.; MacKay, M.; Pickworth, J.; Robertson, J. H.; Shoemaker, C. B.; White, J. G.; Prosen, R. J.; Trueblood, K. N. (1957). "The Structure of Vitamin BFormula I. An Outline of the Crystallographic Investigation of Vitamin BFormula". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 242 (1229): 228. doi:10.1098/rspa.1957.0174.

- ^ Hodgkin, D. C. (1974). "The Bakerian Lecture, 1972: Insulin, its Chemistry and Biochemistry". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 338 (1614): 251. doi:10.1098/rspa.1974.0085.

- ^ Turing, A. M. (1952). "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 237 (641): 37–64. doi:10.1098/rstb.1952.0012.

- ^ Hawking, S. W. (1983). "The Cosmological Constant [and Discussion]". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 310 (1512): 303. doi:10.1098/rsta.1983.0092.

- ^ a b Van Noorden, Richard Royal Society frees up journal archive, 26 Oct 2011

- ^ Murphy, y Samantha Guerilla Activist' Releases 18,000 Scientific Papers, July 22, 2011

External links[edit]

- Henry Oldenburg's copy of vol I & II of Philosophical Transactions, manuscript note on a flyleaf, a receipt signed by the Royal Society’s printer: “Rec. October 18th 1669 from Mr Oldenburgh Eighteen shillings for this voll: of Transactions by me John Martyn”.

- Philosophical Transactions (1665-1886) homepage

- Royal Society Publishing

- Index to free volumes and articles online

- Torrent with 18,592 scientific publications in the public domain 32.48 GiB

Category:Publications established in 1665 Category:Royal Society academic journals Category:Multidisciplinary scientific journals Category:Natural philosophy Category:1665 establishments in England