Western culture

Western culture, sometimes equated with Western civilization, Occidental culture, the Western world, Western society, and European civilization, is the heritage of social norms, ethical values, traditional customs, belief systems, political systems, artifacts and technologies that originated in or are associated with Europe. The term also applies beyond Europe to countries and cultures whose histories are strongly connected to Europe by immigration, colonization, or influence. For example, Western culture includes countries in the Americas and Australasia, whose language and demographic ethnicity majorities are of European descent. Western culture has its roots in Greco-Roman culture from classical antiquity (see Western canon).

Ancient Greece is considered the birthplace of many elements of Western culture, including the development of a democratic system of government and major advances in philosophy, science and mathematics. The expansion of Greek culture into the Hellenistic world of the eastern Mediterranean led to a synthesis between Greek and Near-Eastern cultures,[3] and major advances in literature, engineering, and science, and provided the culture for the expansion of early Christianity and the Greek New Testament.[4][5][6] This period overlapped with and was followed by Rome, which made key contributions in law, government, engineering and political organization.[7] The concept of a "West" dates back to the Roman Empire, where there was a cultural divide between the Greek East and Latin West, a divide that later continued in Medieval Europe between the Catholic Latin Church west and the "Greek" Eastern Orthodox east.

Western culture is characterized by a host of artistic, philosophic, literary and legal themes and traditions. Christianity, including the Roman Catholic Church,[8][9][10] Protestantism[11][12] the Eastern Orthodox Church, and Oriental Orthodoxy,[13][14] has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization since at least the 4th century,[15][16][17][18][19] as did Judaism.[20][21][22][23] Before the Cold War era, the traditional English viewpoint identified Western civilization with the Western Christian (Catholic–Protestant) countries and culture.[24][1] A cornerstone of Western thought, beginning in ancient Greece and continuing through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, is the idea of rationalism in various spheres of life developed by Hellenistic philosophy, scholasticism and humanism. The Catholic Church was for centuries at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws and institutions which constitute Western civilization.[25][26] Empiricism later gave rise to the scientific method, the scientific revolution, and the Age of Enlightenment.

Western culture continued to develop with the Christianisation of Europe during the Middle Ages, the reforms triggered by the Renaissance of the 12th century and 13th century under the influence of the Islamic world via Al-Andalus and Sicily (including the transfer of technology from the East, and Latin translations of Arabic texts on science and philosophy),[27][28][29] and the Italian Renaissance as Greek scholars fleeing the fall of the Byzantine Empire brought classical traditions and philosophy.[30] Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the modern university,[31][32] the modern hospital system,[33] scientific economics,[34][26] and natural law (which would later influence the creation of international law).[35] Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such as human sacrifice, slavery,[36] infanticide and polygamy.[37] The globalization by successive European colonial empires spread European ways of life and European educational methods around the world between the 16th and 20th centuries.[citation needed] European culture developed with a complex range of philosophy, medieval scholasticism, mysticism and Christian and secular humanism.[38][page needed] Rational thinking developed through a long age of change and formation, with the experiments of the Enlightenment and breakthroughs in the sciences. Tendencies that have come to define modern Western societies include the concept of political pluralism, individualism, prominent subcultures or countercultures (such as New Age movements) and increasing cultural syncretism resulting from globalization and human migration.

Terminology

The West as a geographical area is unclear and undefined. More often a country's ideology is what will be used to categorize it as a Western society. There is some disagreement about what nations should or should not be included in the category and at what times. Many parts of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire are considered Western today but were considered Eastern in the past. However, in the past it was also the Eastern Roman Empire that had many features now seen as "Western," preserving Roman law, which was first codified by Justinian in the east,[40] as well as the traditions of scholarship around Plato, Aristotle, and Euclid that were later introduced to Italy during the Renaissance by Greek scholars fleeing the fall of Constantinople.[30] Thus, the culture identified with East and West itself interchanges with time and place (from the ancient world to the modern). Geographically, the "West" of today would include Europe (especially the states that collectively form the European Union) together with extra-European territories belonging to the English-speaking world, the Hispanidad, the Lusosphere; and the Francophonie in the wider context. Since the context is highly biased and context-dependent, there is no agreed definition what the "West" is.

It is difficult to determine which individuals fit into which category and the East–West contrast is sometimes criticized as relativistic and arbitrary.[41][42][43][page needed] Globalism has spread Western ideas so widely that almost all modern cultures are, to some extent, influenced by aspects of Western culture. Stereotyped views of "the West" have been labeled Occidentalism, paralleling Orientalism—the term for the 19th-century stereotyped views of "the East".

As Europeans discovered the wider world, old concepts adapted. The area that had formerly been considered the Orient ("the East") became the Near East as the interests of the European powers interfered with Meiji Japan and Qing China for the first time in the 19th century.[44] Thus the Sino-Japanese War in 1894–1895 occurred in the Far East while the troubles surrounding the decline of the Ottoman Empire simultaneously occurred in the Near East.[a] The term Middle East in the mid-19th century included the territory east of the Ottoman Empire, but West of China—Greater Persia and Greater India—is now used synonymously with "Near East" in most languages.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

The earliest civilizations which influenced the development of Western culture were those of Mesopotamia; the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran: the cradle of civilization.[46][47] Ancient Egypt similarly had a strong influence on Western culture.

The Greeks contrasted themselves with both their Eastern neighbours (such as the Trojans in Iliad) as well as their Western neighbours (who they considered barbarians).[citation needed] Concepts of what is the West arose out of legacies of the Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire. Later, ideas of the West were formed by the concepts of Latin Christendom and the Holy Roman Empire. What is thought of as Western thought today originates primarily from Greco-Roman and Germanic influences, and includes the ideals of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Enlightenment, as well as Christian culture.

Classical West

While the concept of a "West" did not exist until the emergence of the Roman Republic, the roots of the concept can be traced back to Ancient Greece. Since Homeric literature (the Trojan Wars), through the accounts of the Persian Wars of Greeks against Persians by Herodotus, and right up until the time of Alexander the Great, there was a paradigm of a contrast between Greeks and other civilizations. Greeks felt they were the most civilized and saw themselves (in the formulation of Aristotle) as something between the advanced civilisations of the Near East (who they viewed as soft and slavish) and the wild barbarians of most of Europe to the west.

Alexander's conquests led to the emergence of a Hellenistic civilization, representing a synthesis of Greek and Near-Eastern cultures in the Eastern Mediterranean region.[3] The Near-Eastern civilizations of Ancient Egypt and the Levant, which came under Greek rule, became part of the Hellenistic world. The most important Hellenistic centre of learning was Ptolemaic Egypt, which attracted Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, Persian, Phoenician and even Indian scholars.[48] Hellenistic science, philosophy, architecture, literature and art later provided a foundation embraced and built upon by the Roman Empire as it swept up Europe and the Mediterranean world, including the Hellenistic world in its conquests in the 1st century BCE.

Following the Roman conquest of the Hellenistic world, the concept of a "West" arose, as there was a cultural divide between the Greek East and Latin West. The Latin-speaking Western Roman Empire consisted of Western Europe and Northwest Africa, while the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire (later the Byzantine Empire) consisted of the Balkans, Asia Minor, Egypt and Levant. The "Greek" East was generally wealthier and more advanced than the "Latin" West[citation needed]. With the exception of Italia, the wealthiest provinces of the Roman Empire were in the East, particularly Roman Egypt which was the wealthiest Roman province outside of Italia.[49][50] Nevertheless, the Celts in the West created some significant literature in the ancient world whenever they were given the opportunity (an example being the poet Caecilius Statius), and they developed a large amount of scientific knowledge themselves (as seen in their Coligny Calendar).

For about five hundred years, the Roman Empire maintained the Greek East and consolidated a Latin West, but an East–West division remained, reflected in many cultural norms of the two areas, including language. Eventually, the empire became increasingly split into a Western and Eastern part, reviving old ideas of a contrast between an advanced East, and a rugged West. In the Roman world, one could speak of three main directions: North (Celtic tribal states and Parthians), the East (lux ex oriente), and finally the South (Quid novi ex Africa?), the latter conquered after the Punic Wars.

From the time of Alexander the Great (the Hellenistic period), Greek civilization came in contact with Jewish civilization. Christianity would eventually emerge from the syncretism of Hellenic culture, Roman culture, and Second Temple Judaism, gradually spreading across the Roman Empire and eclipsing its antecedents and influences.[51] The rise of Christianity reshaped much of the Greco-Roman tradition and culture; the Christianised culture would be the basis for the development of Western civilization after the fall of Rome (which resulted from increasing pressure from barbarians outside Roman culture). Roman culture also mixed with Celtic, Germanic, and Slavic cultures, which slowly became integrated into Western culture: starting mainly with their acceptance of Christianity.

Medieval West

In a narrow sense, the Medieval West referred specifically to the Catholic "Latin" West, also called "Frankish" during Charlemagne's reign, in contrast to the Orthodox East, where Greek remained the language of the Byzantine Empire. In its broadest sense, the Medieval West refers to the whole of Christendom,[1][54] including both the Catholic West and the Orthodox East.

After the fall of Rome, much of Greco-Roman art, literature, science and even technology were all but lost in the western part of the old empire. However, this would become the centre of a new West. Europe fell into political anarchy, with many warring kingdoms and principalities. Under the Frankish kings, it eventually, and partially, reunified, and the anarchy evolved into feudalism.

Much of the basis of the post-Roman cultural world had been set before the fall of the Empire, mainly through the integration and reshaping of Roman ideas through Christian thought. The Greek and Roman paganism had been completely replaced by Christianity around the 4th and 5th centuries, since it became the official State religion following the baptism of emperor Constantine I. Orthodox Christian Christianity and the Nicene Creed served as a unifying force in Christian parts of Europe, and in some respects replaced or competed with the secular authorities. The Jewish Christian tradition out of which it had emerged was all but extinguished, and antisemitism became increasingly entrenched or even integral to Christendom.[55][56] Art and literature, law, education, and politics were preserved in the teachings of the Church, in an environment that, otherwise, would have probably seen their loss. The Church founded many cathedrals, universities, monasteries and seminaries, some of which continue to exist today.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, many of the classical Greek texts were translated into Arabic and preserved in the medieval Islamic world. The Greek classics along with Arabic science, philosophy and technology were transmitted to Western Europe and translated into Latin, sparking the Renaissance of the 12th century and 13th century.[27][28][29]

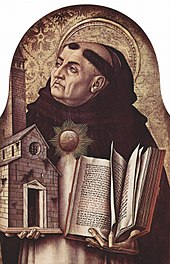

Medieval Christianity is credited with creating the first modern universities.[31][32] The Catholic Church established a hospital system in Medieval Europe that vastly improved upon the Roman valetudinaria[57] and Greek healing temples.[58] These hospitals were established to cater to "particular social groups marginalized by poverty, sickness, and age," according to historian of hospitals, Guenter Risse.[33] Christianity played a role in ending practices common among pagan societies, such as human sacrifice, slavery,[36] infanticide and polygamy.[37] Francisco de Vitoria, a disciple of Thomas Aquinas and a Catholic thinker who studied the issue regarding the human rights of colonized natives, is recognized by the United Nations as a father of international law, and now also by historians of economics and democracy as a leading light for the West's democracy and rapid economic development.[59] Joseph Schumpeter, an economist of the twentieth century, referring to the Scholastics, wrote, "it is they who come nearer than does any other group to having been the 'founders' of scientific economics."[34] Other economists and historians, such as Raymond de Roover, Marjorie Grice-Hutchinson, and Alejandro Chafuen, have also made similar statements. Historian Paul Legutko of Stanford University said the Catholic Church is "at the center of the development of the values, ideas, science, laws, and institutions which constitute what we call Western civilization."[26]

In a broader sense, the Middle Ages, with its fertile encounter between Greek philosophical reasoning and Levantine monotheism was not confined to the West but also stretched into the old East. The philosophy and science of Classical Greece was largely forgotten in Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire, other than in isolated monastic enclaves (notably in Ireland, which had become Christian but was never conquered by Rome).[60] The learning of Classical Antiquity was better preserved in the Byzantine Eastern Roman Empire. Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis Roman civil law code was created in the East in his capital of Constantinople,[40] and that city maintained trade and intermittent political control over outposts such as Venice in the West for centuries. Classical Greek learning was also subsumed, preserved and elaborated in the rising Eastern world, which gradually supplanted Roman-Byzantine control as a dominant cultural-political force. Thus, much of the learning of classical antiquity was slowly reintroduced to European civilization in the centuries following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The rediscovery of the Justinian Code in Western Europe early in the 10th century rekindled a passion for the discipline of law, which crossed many of the re-forming boundaries between East and West. In the Catholic or Frankish west, Roman law became the foundation on which all legal concepts and systems were based. Its influence is found in all Western legal systems, although in different manners and to different extents. The study of canon law, the legal system of the Catholic Church, fused with that of Roman law to form the basis of the refounding of Western legal scholarship. During the Reformation and Enlightenment, the ideas of civil rights, equality before the law, procedural justice, and democracy as the ideal form of society began to be institutionalized as principles forming the basis of modern Western culture, particularly in Protestant regions.

In the 14th century, starting from Italy and then spreading throughout Europe,[61] there was a massive artistic, architectural, scientific and philosophical revival, as a result of the Christian revival of Greek philosophy, and the long Christian medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities.[62] This period is commonly referred to as the Renaissance. In the following century, this process was further enhanced by an exodus of Greek Christian priests and scholars to Italian cities such as Venice after the end of the Byzantine Empire with the fall of Constantinople.

From Late Antiquity, through the Middle Ages, and onwards, while Eastern Europe was shaped by the Orthodox Church, Southern and Central Europe were increasingly stabilized by the Catholic Church which, as Roman imperial governance faded from view, was the only consistent force in Western Europe.[63] In 1054 came the Great Schism that, following the Greek East and Latin West divide, separated Europe into religious and cultural regions present to this day. Until the Age of Enlightenment,[64] Christian culture took over as the predominant force in Western civilization, guiding the course of philosophy, art, and science for many years.[63][65] Movements in art and philosophy, such as the Humanist movement of the Renaissance and the Scholastic movement of the High Middle Ages, were motivated by a drive to connect Catholicism with Greek and Arab thought imported by Christian pilgrims.[66][67][68] However, due to the division in Western Christianity caused by the Protestant Reformation and the Enlightenment, religious influence—especially the temporal power of the Pope—began to wane.[69][70]

From the late 15th century to the 17th century, Western culture began to spread to other parts of the world through explorers and missionaries during the Age of Discovery, and by imperialists from the 17th century to the early 20th century. During the Great Divergence, a term coined by Samuel Huntington[71] the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilization of the time, eclipsing Qing China, Mughal India, Tokugawa Japan, and the Ottoman Empire. The process was accompanied and reinforced by the Age of Discovery and continued into the modern period. Scholars have proposed a wide variety of theories to explain why the Great Divergence happened, including lack of government intervention, geography, colonialism, and customary traditions.

Modern era

Coming into the modern era, the historical understanding of the East–West contrast—as the opposition of Christendom to its geographical neighbors—began to weaken. As religion became less important, and Europeans came into increasing contact with far away peoples, the old concept of Western culture began a slow evolution towards what it is today. The Age of Discovery faded into the Age of Enlightenment of the 18th century, during which cultural and intellectual forces in Western Europe emphasized reason, analysis, and individualism rather than traditional lines of authority. It challenged the authority of institutions that were deeply rooted in society, such as the Catholic Church; there was much talk of ways to reform society with toleration, science and skepticism.

Philosophers of the Enlightenment included Francis Bacon, René Descartes, John Locke, Baruch Spinoza, Voltaire (1694–1778), David Hume, and Immanuel Kant.[72] influenced society by publishing widely read works. Upon learning about enlightened views, some rulers met with intellectuals and tried to apply their reforms, such as allowing for toleration, or accepting multiple religions, in what became known as enlightened absolutism. New ideas and beliefs spread around Europe and were fostered by an increase in literacy due to a departure from solely religious texts. Publications include Encyclopédie (1751–72) that was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. The Dictionnaire philosophique (Philosophical Dictionary, 1764) and Letters on the English (1733) written by Voltaire spread the ideals of the Enlightenment.

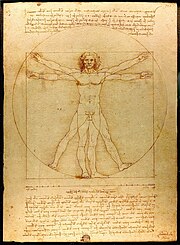

Coinciding with the Age of Enlightenment was the scientific revolution, spearheaded by Newton. This included the emergence of modern science, during which developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed views of society and nature.[73][74][75][76][77][78] While its dates are disputed, the publication in 1543 of Nicolaus Copernicus's De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) is often cited as marking the beginning of the scientific revolution, and its completion is attributed to the "grand synthesis" of Newton's 1687 Principia.

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in the period from about 1760 to sometime between 1820 and 1840. This included going from hand production methods to machines, new chemical manufacturing and iron production processes, improved efficiency of water power, the increasing use of steam power, and the development of machine tools.[79] These transitions began in Great Britain, and spread to Western Europe and North America within a few decades.[80]

The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. In particular, average income and population began to exhibit unprecedented sustained growth. Some economists say that the major impact of the Industrial Revolution was that the standard of living for the general population began to increase consistently for the first time in history, although others have said that it did not begin to meaningfully improve until the late 19th and 20th centuries.[82][83][84] The precise start and end of the Industrial Revolution is still debated among historians, as is the pace of economic and social changes.[85][86][87][88] GDP per capita was broadly stable before the Industrial Revolution and the emergence of the modern capitalist economy,[89] while the Industrial Revolution began an era of per-capita economic growth in capitalist economies.[90] Economic historians are in agreement that the onset of the Industrial Revolution is the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals, plants[91] and fire.

The First Industrial Revolution evolved into the Second Industrial Revolution in the transition years between 1840 and 1870, when technological and economic progress continued with the increasing adoption of steam transport (steam-powered railways, boats, and ships), the large-scale manufacture of machine tools and the increasing use of machinery in steam-powered factories.[92][93][94]

Arts and humanities

What is distinctive of European art is that it comments on so many levels-religious, humanistic, satirical, metaphysical, and the purely physical.[95]

Some cultural and artistic modalities are characteristically Western in origin and form. While dance, music, visual art, story-telling, and architecture are human universals, they are expressed in the West in certain characteristic ways.

In Western dance, music, plays and other arts, the performers are only very infrequently masked. There are essentially no taboos against depicting a god, or other religious figures, in a representational fashion.

European art pays deep tribute to human suffering.[95]

Music

In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[96] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[97]

The symphony, concerto, sonata, opera, and oratorio have their origins in Italy. Many musical instruments developed in the West have come to see widespread use all over the world; among them are the violin, piano, pipe organ, saxophone, trombone, clarinet, accordion, and the theremin. In turn, most European instruments have roots in earlier Eastern instruments that were adopted from the medieval Islamic world.[98] The solo piano, symphony orchestra, and the string quartet are also significant musical innovations of the West.

-

Johann Sebastian Bach, 1685-1750

-

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1756-1791

-

Ludwig van Beethoven, 1770-1827

-

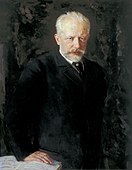

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, 1840-1893

Painting and photography

Jan van Eyck, among other renaissance painters, made great advances in oil painting, and perspective drawings and paintings had their earliest practitioners in Florence.[99] In art, the Celtic knot is a very distinctive Western repeated motif. Depictions of the nude human male and female in photography, painting, and sculpture are frequently considered to have special artistic merit. Realistic portraiture is especially valued.

Photography, and the motion picture as both a technology and basis for entirely new art forms were also developed in the West.

-

Restoration of a fresco from an Ancient Roman villa bedroom, circa 50-40 BC, dimensions of the room: 265.4 x 334 x 583.9 cm, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

-

Mona Lisa, by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1503–1506, perhaps continuing until circa 1517, oil on poplar panel, 77 cm × 53 cm, Louvre, (Paris)

-

Dance at Le moulin de la Galette, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1876, oil on canvas, height: 131 cm, Musée d'Orsay (Paris)

-

Photo of the interior of the apartment of Eugène Atget, taken in 1910 in Paris

Dance and performing arts

The ballet is a distinctively Western form of performance dance.[100] The ballroom dance is an important Western variety of dance for the elite. The polka, the square dance, and the Irish step dance are very well known Western forms of folk dance.

Greek and Roman theatre are considered the antecedents of modern theatre, and forms such as medieval theatre, passion plays, morality plays, and commedia dell'arte are considered highly influential. Elizabethan theatre, with such luminaries as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, and Ben Jonson, is considered one of the most formative and important eras for modern drama.

The soap opera, a popular culture dramatic form, originated in the United States first on radio in the 1930s, then a couple of decades later on television. The music video was also developed in the West in the middle of the 20th century. Musical theatre was developed in the West in the 19th and 20th Centuries, from music hall, comic opera, and Vaudeville; with significant contributions from the Jewish diaspora, African-Americans, and other marginalized peoples.[101][102][103]

Literature

While epic literary works in verse such as the Mahabharata and Homer's Iliad are ancient and occurred worldwide, the prose novel as a distinct form of storytelling, with developed, consistent human characters and, typically, some connected overall plot (although both of these characteristics have sometimes been modified and played with in later times), was popularized by the West[104] in the 17th and 18th centuries. Of course, extended prose fiction had existed much earlier; both novels of adventure and romance in the Hellenistic world and in Heian Japan. Both Petronius' Satyricon (c. 60 CE) and the Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (c. 1000 CE) have been cited as the world's first major novel but they had a very limited long-term impact on literary writing beyond their own day until much more recent times.

The novel, which made its appearance in the 18th century, is an essentially European creation. Chinese and Japanese literature contain some works that may be thought of as novels, but only the European novel is couched in terms of a personal analysis of personal dilemmas.[95]

As in its artistic tradition, European literature pays deep tribute to human suffering.[95]

The validity of reason was postulated in both Christian philosophy and the Greco-Roman classics.[95]

Christianity laid a stress on the inward aspects of actions and on motives, notions that were foreign to the ancient world. This subjectivity, which grew out of the Christian belief that man could achieve a personal union with God, resisted all challenges and made itself the fulcrum on which all literary exposition turned, including the 20th-21st century novels.[95]

Tragedy, from its ritually and mythologically inspired Greek origins to modern forms where struggle and downfall are often rooted in psychological or social, rather than mythical, motives, is also widely considered a specifically European creation and can be seen as a forerunner of some aspects of both the novel and of classical opera.

Architecture

Important Western architectural motifs include the Doric, Corinthian, and Ionic columns, and the Romanesque, Gothic, Baroque, and Victorian styles are still widely recognised, and used even today, in the West. Much of Western architecture emphasizes repetition of simple motifs, straight lines and expansive, undecorated planes. A modern ubiquitous architectural form that emphasizes this characteristic is the skyscraper, their modern equivalent first developed in New York, London, and Chicago. The predecessor of the skyscraper can be found in the medieval towers erected in Bologna.

-

Stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, completed in 1248, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1220

-

Saint Basil's Cathedral, built from 1555 to 1561, in the Red Square (Moscow), with its extraordinary onion-shaped domes, painted in bright colors

-

The Palais Garnier in Paris, built between 1861 and 1875, a Beaux-Arts masterpiece

Scientific and technological inventions and discoveries

A notable feature of Western culture is its strong emphasis and focus on innovation and invention through science and technology, and its ability to generate new processes, materials and material artifacts with its roots dating back to the Ancient Greeks. The scientific method as "a method or procedure that has characterized natural science since the 17th century, consisting in systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, and the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses" was fashioned by the 17th-century Italian Galileo Galilei,[106][107] with roots in the work of medieval scholars such as the 11th-century Iraqi physicist Ibn al-Haytham[108][109] and the 13th-century English friar Roger Bacon.[110]

The Western world has been the leading force in the technological and scientific disciplines in modern history. According to the Dictionary of Scientific Biography (DoSB) sponsored by the American Council of Learned Societies, 81 percent of the most significant scientists and mathematicians come from Europe compared to 76 percent in the Human Accomplishment set, numbers that rise to 94 and 91 percent respectively when the United States and Canada are included.[111] The United Kingdom, France, Germany and Italy alone account for 72 percent of all the significant scientific figures in science from 1400 to 1950. Add in Russia and the Netherlands, and 80 percent of all significant figures are accounted for.[112]

By the will of the Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel the Nobel Prize were established in 1895. The prizes in Chemistry, Literature, Peace, Physics, and Physiology or Medicine were first awarded in 1901.[113] The percentage of ethnically European noble prize winners during the first and second halves of the 20th century were respectively 98 and 94 percent.[114] A study by the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) – Japan's equivalent of the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) – concluded that 54% of the world's most important inventions were British. Of the rest, 25% were American and 5% Japanese.[115]

The West is credited with the development of the steam engine and adapting its use into factories, and for the generation of electric power.[116] The electrical motor, dynamo, transformer, electric light, and most of the familiar electrical appliances, were inventions of the West.[117][118][119][120] The Otto and the Diesel internal combustion engines are products whose genesis and early development were in the West.[121][122] Nuclear power stations are derived from the first atomic pile constructed in Chicago in 1942.[123]

Communication devices and systems including the telegraph, the telephone, radio, television, communications and navigation satellites, mobile phone, and the Internet were all invented by Westerners.[124][125][126][127][128][129][130][131] The pencil, ballpoint pen, Cathode ray tube, liquid-crystal display, light-emitting diode, camera, photocopier, laser printer, ink jet printer, plasma display screen and world wide web were also invented in the West.[132][133][134][135][136][137]

Ubiquitous materials including aluminum, clear glass, synthetic rubber, synthetic diamond and the plastics polyethylene, polypropylene, polyvinyl chloride and polystyrene were discovered and developed or invented in the West. Iron and steel ships, bridges and skyscrapers first appeared in the West. Nitrogen fixation and petrochemicals were invented by Westerners. Most of the elements were discovered and named in the West, as well as the contemporary atomic theories to explain them.[citation needed]

The transistor, integrated circuit, memory chip, and computer were all first seen in the West. The ship's chronometer, the screw propeller, the locomotive, bicycle, automobile, and airplane were all invented in the West. Eyeglasses, the telescope, the microscope and electron microscope, all the varieties of chromatography, protein and DNA sequencing, computerised tomography, nuclear magnetic resonance, x-rays, and light, ultraviolet and infrared spectroscopy, were all first developed and applied in Western laboratories, hospitals and factories.[citation needed]

In medicine, the pure antibiotics were created in the West. The method of preventing Rh disease, the treatment of diabetes, and the germ theory of disease were discovered by Westerners. The eradication of smallpox, was led by a Westerner, Donald Henderson. Radiography, computed tomography, positron emission tomography and medical ultrasonography are important diagnostic tools developed in the West. Other important diagnostic tools of clinical chemistry, including the methods of spectrophotometry, electrophoresis and immunoassay, were first devised by Westerners. So were the stethoscope, the electrocardiograph, and the endoscope. Vitamins, hormonal contraception, hormones, insulin, beta blockers and ACE inhibitors, along with a host of other medically proven drugs, were first utilized to treat disease in the West. The double-blind study and evidence-based medicine are critical scientific techniques widely used in the West for medical purposes.[citation needed]

In mathematics, calculus, statistics, logic, vectors, tensors and complex analysis, group theory and topology were developed by Westerners.[138][139][140][141][142][143][144] In biology, evolution, chromosomes, DNA, genetics and the methods of molecular biology are creations of the West. In physics, the science of mechanics and quantum mechanics, relativity, thermodynamics, and statistical mechanics were all developed by Westerners. The discoveries and inventions by Westerners in electromagnetism include Coulomb's law (1785), the first battery (1800), the unity of electricity and magnetism (1820), Biot–Savart law (1820), Ohm's Law (1827), and Maxwell's equations (1871). The atom, nucleus, electron, neutron and proton were all unveiled by Westerners.[citation needed]

In business, economics, and finance, double entry bookkeeping, credit cards, and the charge card were all first used in the West.[145][146]

Westerners are also known for their explorations of the globe and outer space. The first expedition to circumnavigate the Earth (1522) was by Westerners, as well as the first journey to the South Pole (1911), and the first Moon landing (1969).[147][148] The landing of robots on Mars (2004 and 2012) and on an asteroid (2001), the Voyager 2 explorations of the outer planets (Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989), Voyager 1's passage into interstellar space (2013), and New Horizons' flyby of Pluto (2015) were significant recent Western achievements.[149][150][151][152][153]

Media

The roots of modern-day Western mass media can be traced back to the late 15th century, when printing presses began to operate throughout Western Europe. The emergence of news media in the 17th century has to be seen in close connection with the spread of the printing press, from which the publishing press derives its name.[154]

In the 16th century, a decrease in the preeminence of Latin in its literary use, along with the impact of economic change, the "discoveries" arising from trade and travel, navigation to the "new" world, science and arts and the development of increasingly rapid communications through print led to a rising corpus of vernacular media content in Western Europe.[155]

After the launch of the satellite Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union in 1957, satellite transmission technology was dramatically realised, with the U.S. launching Telstar in 1962 linking live media broadcasts from the UK to the US. The first digital broadcast satellite (DBS) system began transmitting in America in 1975.[156]

Beginning in the 1990s, the Internet has contributed to a tremendous increase in the accessibility of Western media content. Departing from media offered in bundled content packages (magazines, CDs, television and radio slots), the Internet has primarily offered unbundled content items (articles, audio and video files).[157]

Religion

The native religions of Europe were polytheistic but not homogenous — however, they were similar insofar as they were predominantly Indo-European in origin. Roman religion was similar to but not the same as Hellenic religion — likewise for indigenous Germanic polytheism, Celtic polytheism and Slavic polytheism. Western culture, for at least the last 1000 years, has been considered nearly synonymous with Christian culture.[1] Before this time many Europeans from the north, especially Scandinavians, remained polytheistic, though southern Europe was predominantly Christian from the 5th century onwards.

Western culture, throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Western Christian culture, and many of the population of the Western hemisphere could broadly be described as cultural Christians. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom"; many even attribute Christianity as the link that created a unified European identity.[1]

As in other areas, the Jewish diaspora and Judaism exist in the Western world. Non-European groups, and Jews in particular, have been subjected to intense racism, ethnic and religious hatred, xenophobia, discrimination, and persecution in the West.[158][159] This has included pogroms, forced conversion, displacement, segregation and ghettos, ethnic cleansing, genocide, and other forms of violence and prejudice.[160][161][162]

Religion has waned in Europe, where people who are agnostic or atheist make up about 18% of the European population today.[163] In particular, over half of the populations of the Czech Republic (79% of the population was agnostic, atheist or irreligious), the United Kingdom (~25%),[164][deprecated source] Germany (25–33%),[165] France (30–35%)[166][167][168] and the Netherlands (39–44%) are agnostic or atheist.

However, per another survey by Pew Research Center from 2011, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the Western world where 70–84% are Christians,[169] According to this survey, 76% of Europeans described themselves as Christians,[169][170][171] and about 86% of the Americas population identified themselves as Christians,[172] (90% in Latin America and 77% in North America).[173] And 73% in Oceania are self-identify as Christian, and 76% in South Africa is Christian.[169]

According to new polls about religiosity in the European Union in 2012 by Eurobarometer, Christianity is the largest religion in the European Union, accounting for 72% of the EU population.[174] Catholics are the largest Christian group, accounting for 48% of the EU population, while Protestants make up 12%, Eastern Orthodox make up 8% and other Christians make up 4%.[175] Non-believers/Agnostics account for 16%,[174] atheists account for 7%,[174] and Muslims account for 2%.[174]

Throughout the Western world there are increasing numbers of people who seek to revive the indigenous religions of their European ancestors; such groups include Germanic, Roman, Hellenic, Celtic, Slavic, and polytheistic reconstructionist movements. Likewise, Wicca, New Age spirituality and other neo-pagan belief systems enjoy notable minority support in Western states.

Sport

Since classical antiquity, sport has been an important facet of Western cultural expression. A wide range of sports were already established by the time of Ancient Greece and the military culture and the development of sports in Greece influenced one another considerably. Sports became such a prominent part of their culture that the Greeks created the Olympic Games, which in ancient times were held every four years in a small village in the Peloponnesus called Olympia. Baron Pierre de Coubertin, a Frenchman, instigated the modern revival of the Olympic movement. The first modern Olympics were held at 1896 Athens in.

The Romans built immense structures such as the Colisseum in Rome to house their festivals of sport. The Romans exhibited a passion for blood sports, such as the infamous Gladiatorial battles that pitted contestants against one another in a fight to the death. The Olympic Games revived many of the sports of Classical Antiquity—such as Greco-Roman wrestling, discus and javelin. The sport of bullfighting is a traditional spectacle of Spain, Portugal, southern France, and some Latin American countries. It traces its roots to prehistoric bull worship and sacrifice and is often linked to Rome, where many human-versus-animal events were held. Bullfighting spread from Spain to its American colonies, and in the 19th century to France, where it developed into a distinctive form in its own right.

Jousting and hunting were popular sports in the Western Europe of the Middle Ages, and the aristocratic classes of Europe developed passions for leisure activities. A great number of the popular global sports were first developed or codified in Europe. The modern game of golf originated in Scotland, where the first written record of golf is James II's banning of the game in 1457, as an unwelcome distraction to learning archery. The Industrial Revolution that began in Britain in the 18th Century brought increased leisure time, leading to more time for citizens to attend and follow spectator sports, greater participation in athletic activities, and increased accessibility. These trends continued with the advent of mass media and global communication. The bat and ball sport of cricket was first played in England during the 16th century and was exported around the globe via the British Empire. A number of popular modern sports were devised or codified in Britain during the 19th Century and obtained global prominence—these include ping pong, modern tennis, association football, netball and rugby.

Football (also known as soccer) remains hugely popular in Europe, but has grown from its origins to be known as the world game. Similarly, sports such as cricket, rugby, and netball were exported around the world, particularly among countries in the Commonwealth of Nations, thus India and Australia are among the strongest cricketing nations, while victory in the Rugby World Cup has been shared among the Western states of New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and England.

Australian Rules Football, an Australian variation of football with similarities to Gaelic football and rugby evolved in the British colony of Victoria in the mid-19th century. The United States also developed unique variations of English sports. English migrants took antecedents of baseball to America during the colonial period. The history of American football can be traced to early versions of rugby football and association football. Many games known as "football" were being played at colleges and universities in the United States in the first half of the 19th century. American football resulted from several major divergences from rugby, most notably the rule changes instituted by Walter Camp, the "Father of American Football". Basketball was invented in 1891 by James Naismith, a Canadian physical education instructor working in Springfield, Massachusetts in the United States.

Themes and traditions

Western culture has developed many themes and traditions, the most significant of which are:[citation needed]

- Greco-Roman classic letters, arts, architecture, philosophical and cultural tradition, which include the influence of preeminent authors and philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Homer, Virgil, and Cicero, as well as a long mythologic tradition.

- Christian ethical, philosophical, and mythological tradition, stemming largely from the Christian Bible, particularly the New Testament Gospels.

- Monasteries, schools, libraries, books, book making, universities, teaching, education, and lecture halls.

- A tradition of the importance of the rule of law.

- Secular humanism, rationalism and Enlightenment thought. This set the basis for a new critical attitude and open questioning of religion, favouring freethinking and questioning of the church as an authority, which resulted in open-minded and reformist ideals inside, such as liberation theology, which partly adopted these currents, and secular and political tendencies such as laicism, agnosticism and atheism.

- Generalized usage of some form of the Latin or Greek alphabet, and derived forms, such as Cyrillic, used by those southern and eastern Slavic countries of Christian Orthodox tradition, historically under the Byzantine Empire and later within the Russian czarist or Soviet area of influence. Other variants of the Latin or Greek alphabets are found in the Gothic and Coptic alphabets, which historically superseded older scripts, such as runes, and the Egyptian Demotic and Hieroglyphic systems.

- Natural law, human rights, constitutionalism, parliamentarism (or presidentialism) and formal liberal democracy in recent times—prior to the 19th century, most Western governments were still monarchies.

- A large influence, in modern times, of many of the ideals and values developed and inherited from Romanticism.

- An emphasis on, and use of, science as a means of understanding the natural world and humanity's place in it.

- More pronounced use and application of innovation and scientific developments, as well as a more rational approach to scientific progress (what has been known as the scientific method), as opposed to more empiric discoveries in the Eastern world.

See also

Notes

- ^ British archaeologist D.G. Hogarth published The Nearer East in 1902, which helped to define the term and its extent, including Albania, Montenegro, southern Serbia and Bulgaria, Greece, Egypt, all Ottoman lands, the entire Arabian Peninsula, and Western parts of Iran.

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Krauskopf, I. 2006. "The Grave and Beyond." The Religion of the Etruscans. edited by N. de Grummond and E. Simon. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. vii, p. 73-75.

- ^ a b Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- ^ Russo, Lucio (2004). The Forgotten Revolution: How Science Was Born in 300 BC and Why It Had To Be Reborn. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 3-540-20396-6.

- ^ "Hellenistic Age". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - ^ Green, P (2008). Alexander The Great and the Hellenistic Age. p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-7538-2413-9.

- ^ Jonathan Daly (19 December 2013). The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization. A&C Black. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-1-4411-1851-6.

- ^ Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2016). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1715 (Cengage Learning ed.). p. 156. ISBN 978-1-305-63347-6.

- ^ Neill, Thomas Patrick (1957). Readings in the History of Western Civilization, Volume 2 (Newman Press ed.). p. 224.

- ^ O'Collins, Gerald; Farrugia, Maria (2003). Catholicism: The Story of Catholic Christianity. Oxford University Press. p. v (preface). ISBN 978-0-19-925995-3.

- ^ Karl Heussi, Kompendium der Kirchengeschichte, 11. Auflage (1956), Tübingen (Germany), pp. 317–319, 325–326

- ^ The Protestant Heritage, Britannica

- ^ McNeill, William H. (2010). History of Western Civilization: A Handbook (University of Chicago Press ed.). p. 204. ISBN 978-0-226-56162-2.

- ^ Faltin, Lucia; Melanie J. Wright (2007). The Religious Roots of Contemporary European Identity (A&C Black ed.). p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8264-9482-5.

- ^ Roman Catholicism, "Roman Catholicism, Christian church that has been the decisive spiritual force in the history of Western civilization". Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Caltron J.H Hayas, Christianity and Western Civilization (1953), Stanford University Press, p. 2: That certain distinctive features of our Western civilization—the civilization of western Europe and of America—have been shaped chiefly by Judaeo–Graeco–Christianity, Catholic and Protestant.

- ^ Jose Orlandis, 1993, "A Short History of the Catholic Church," 2nd edn. (Michael Adams, Trans.), Dublin:Four Courts Press, ISBN 1851821252, preface, see [1], accessed 8 December 2014. p. (preface)

- ^ Thomas E. Woods and Antonio Canizares, 2012, "How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization," Reprint edn., Washington, D.C.: Regnery History, ISBN 1596983280, see accessed 8 December 2014. p. 1: "Western civilization owes far more to Catholic Church than most people—Catholic included—often realize. The Church in fact built Western civilization."

- ^ Marvin Perry (1 January 2012). Western Civilization: A Brief History, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-1-111-83720-4.

- ^ Noble, Thomas F. X. (1 January 2013). Western civilization : beyond boundaries (7th ed.). Boston, MA. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-133-60271-2. OCLC 858610469.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Marvin Perry; Myrna Chase; James Jacob; Margaret Jacob; Jonathan W Daly (2015). Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: To 1789. Cengage Learning. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-305-44548-2.

- ^ Hengel, Martin (2003). Judaism and Hellenism : studies in their encounter in Palestine during the early Hellenistic period. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-186-0. OCLC 52605048.

- ^ Porter, Stanley E. (2013). Early Christianity in its Hellenistic context. Volume 2, Christian origins and Hellenistic Judaism : social and literary contexts for the New Testament. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004234765. OCLC 851653645.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold (1947). A Study of History: Abridgement of, Volumes 1–6 (Oxford University Press ed.). p. 155. ISBN 978-0-19-982669-8.

- ^ Woods, Thomas E. (2005). How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization. Washington, DC: Regency Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89526-038-3.

- ^ a b c "Review of How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization by Thomas Woods, Jr". National Review Book Service. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ^ a b Haskins, Charles Homer (1927), The Renaissance of the Twelfth Century, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-6747-6075-2

- ^ a b George Sarton: A Guide to the History of Science Waltham Mass. U.S.A. 1952

- ^ a b Burnett, Charles. "The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Translation Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century," Science in Context, 14 (2001): 249–288.

- ^ a b Geanakoplos, Deno John. Constantinople and the West: essays on the late Byzantine (Palaeologan) and Italian Renaissances and the Byzantine and Roman churches. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

- ^ a b Rüegg, Walter: "Foreword. The University as a European Institution", in: A History of the University in Europe. Vol. 1: Universities in the Middle Ages, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-36105-2, pp. xix–xx

- ^ a b Verger 1999

- ^ a b Risse, Guenter B. (April 1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-19-505523-8.

- ^ a b Schumpeter, Joseph (1954). History of Economic Analysis. London: Allen & Unwin.

- ^ Cf. Jeremy Waldron (2002), God, Locke, and Equality: Christian Foundations in Locke's Political Thought, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (UK), ISBN 978-0-521-89057-1, pp. 189, 208

- ^ a b Chadwick, Owen p. 242.

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 309.

- ^ Sailen Debnath, 2010, "Secularism: Western and Indian," New Delhi, India:Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 8126913665.[page needed]

- ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (2 August 2011). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon & Schuster. pp. 151–154. ISBN 978-1-4516-2897-5.

- ^ a b Kaiser, Wolfgang (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Roman Law. pp. 119–148.

- ^ Yin Cheong Cheng, New Paradigm for Re-engineering Education. p. 369

- ^ Ainslie Thomas Embree, Carol Gluck, Asia in Western and World History: A Guide for Teaching. p. xvi

- ^ Kwang-Sae Lee, East and West: Fusion of Horizons[page needed]

- ^ Davidson, Roderic H. (1960). "Where is the Middle East?". Foreign Affairs. 38 (4): 665–75. doi:10.2307/20029452. JSTOR 20029452.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Huntington, Samuel P. (1991). Clash of Civilizations (6th ed.). Washington, DC. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-684-84441-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Huntington, Samuel P. (2001). El choque de las civilizaciones y la reconfiguración del orden undial (PDF) (in Spanish). Translated by José Pedro Tosaus Abadía (1st ed.). Buenos Aires: Paidós. ISBN 950-12-5429-1. - ^ Jacobus Bronowski; The Ascent of Man; Angus & Robertson, 1973 ISBN 0-563-17064-6

- ^ Geoffrey Blainey; A Very Short History of the World; Penguin Books, 2004

- ^ George G. Joseph (2000). The Crest of the Peacock, p. 7-8. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00659-8.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2007), Contours of the World Economy, 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History, p. 55, table 1.14, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-922721-1

- ^ Hero (1899). "Pneumatika, Book ΙΙ, Chapter XI". Herons von Alexandria Druckwerke und Automatentheater (in Greek and German). Translated by Wilhelm Schmidt. Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. pp. 228–232.

- ^ Gordon, Cyrus H., The Common Background of the Greek and Hebrew Civilasations, W. W. Norton and Company, New York 1965

- ^ Fortenberry, Diane (2017). THE ART MUSEUM. Phaidon. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7148-7502-6.

- ^ Elisheva Carlebach; Jacob J. Schacter (25 November 2011). New Perspectives on Jewish-Christian Relations. BRILL. p. 38. ISBN 978-90-04-22117-8.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. The Age of Enlightenment: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Nicholls, William (1995). Christian antisemitism : a history of hate (1st Jason Aronson softcover ed.). Northvale, New Jersey. ISBN 978-1-56821-519-8. OCLC 34892303.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gager, John G. (1983). The origins of anti-semitism : attitudes toward Judaism in pagan and Christian antiquity. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503607-7. OCLC 9112202.

- ^ "Valetudinaria". broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Risse, Guenter B. (15 April 1999). Mending Bodies, Saving Souls: A History of Hospitals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974869-3.

- ^ de Torre, Fr. Joseph M. (1997). "A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Modern Democracy, Equality, and Freedom Under the Influence of Christianity". Catholic Education Resource Center.

- ^ "How The Irish Saved Civilisation", by Thomas Cahill, 1995[page needed]

- ^ Burke, P., The European Renaissance: Centre and Peripheries (1998)

- ^ Grant God and Reason p. 9

- ^ a b Koch, Carl (1994). The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. Early Middle Ages: St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "The Age of Enlightenment". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "High Middle Ages". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Renaissance". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Dawson, Christopher; Glenn Olsen (1961). Crisis in Western Education (reprint ed.). p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8132-1683-6.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Reformation". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Koch, Carl (1994). "Enlightenment". The Catholic Church: Journey, Wisdom, and Mission. St. Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-298-4.

- ^ Frank 2001.

- ^ Sootin, Harry. "Isaac Newton." New York, Messner (1955)

- ^ Galileo Galilei, Two New Sciences, trans. Stillman Drake, (Madison: Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1974), pp. 217, 225, 296–97.

- ^ Ernest A. Moody (1951). "Galileo and Avempace: The Dynamics of the Leaning Tower Experiment (I)". Journal of the History of Ideas. 12 (2): 163–93. doi:10.2307/2707514. JSTOR 2707514.

- ^ Marshall Clagett, The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages, (Madison, Univ. of Wisconsin Pr., 1961), pp. 218–19, 252–55, 346, 409–16, 547, 576–78, 673–82; Anneliese Maier, "Galileo and the Scholastic Theory of Impetus," pp. 103–23 in On the Threshold of Exact Science: Selected Writings of Anneliese Maier on Late Medieval Natural Philosophy, (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Pr., 1982).

- ^ Hannam, p. 342

- ^ E. Grant, The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1996), pp. 29–30, 42–47.

- ^ "Scientific Revolution". Encarta. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- ^ Landes 1969, p. 40

- ^ Landes 1969

- ^ Watt steam engine File: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ^ Lucas, Robert E., Jr. (2002). Lectures on Economic Growth. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 109–10. ISBN 978-0-674-01601-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feinstein, Charles (September 1998). "Pessimism Perpetuated: Real Wages and the Standard of Living in Britain during and after the Industrial Revolution". Journal of Economic History. 58 (3): 625–58. doi:10.1017/s0022050700021100.

- ^ Szreter, Simon; Mooney, Graham (February 1998). "Urbanization, Mortality, and the Standard of Living Debate: New Estimates of the Expectation of Life at Birth in Nineteenth-Century British Cities". The Economic History Review. 51 (1): 104. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00084.

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd., p. 27 ISBN 0-349-10484-0

- ^ Joseph E Inikori. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01079-9.

- ^ Berg, Maxine; Hudson, Pat (1992). "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution" (PDF). The Economic History Review. 45 (1): 24–50. doi:10.2307/2598327. JSTOR 2598327.

- ^ Julie Lorenzen. "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution". Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- ^ Robert Lucas Jr. (2003). "The Industrial Revolution". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

it is fairly clear that up to 1800 or maybe 1750, no society had experienced sustained growth in per capita income. (Eighteenth century population growth also averaged one-third of 1 percent, the same as production growth.) That is, up to about two centuries ago, per capita incomes in all societies were stagnated at around $400 to $800 per year.

- ^ Lucas, Robert (2003). "The Industrial Revolution Past and Future". Archived from the original on 27 November 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

[consider] annual growth rates of 2.4 percent for the first 60 years of the 20th century, of 1 percent for the entire 19th century, of one-third of 1 percent for the 18th century

- ^ McCloskey, Deidre (2004). "Review of The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain (edited by Roderick Floud and Paul Johnson), Times Higher Education Supplement, 15 January 2004".

- ^ Taylor, George Rogers (1951). The Transportation Revolution, 1815–1860. ISBN 978-0-87332-101-3. No name is given to the transition years. The "Transportation Revolution" began with improved roads in the late 18th century.

- ^ Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- ^ Hunter 1985

- ^ a b c d e f Deak, Istvan (1996). Encyclopedia Americana. p. 688.

- ^ Hall, p. 100.

- ^ Murray, p. 45.

- ^ Sachs, Curt (1940), The History of Musical Instruments, Dover Publications, p. 260, ISBN 978-0-486-45265-4

- ^ Barzun, p. 73

- ^ Barzun, p. 329

- ^ Lane, Stewart F. (2011). Jews on Broadway : an historical survey of performers, playwrights, composers, lyricists and producers. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5917-9. OCLC 668182929.

- ^ Most, Andrea (2004). Making Americans : Jews and the Broadway musical. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01165-6. OCLC 52520631.

- ^ Jones, John Bush (2003). Our musicals, ourselves : a social history of the American musical theater. Hanover: Brandeis University Press, published by University Press of New England. ISBN 978-1-61168-223-6. OCLC 654535012.

- ^ Barzun, p. 380

- ^ Graduation through the ages http://www.canterbury.ac.nz/graduation/grad-history.shtml

- ^ "scientific method", Oxford Dictionaries: British and World English, 2016, retrieved 28 May 2016

- ^ Morris Kline (1985) Mathematics for the nonmathematician. Courier Dover Publications. p. 284. ISBN 0-486-24823-2

- ^ Jim Al-Khalili (4 January 2009). "The 'first true scientist'". BBC News.

- ^ Tracey Tokuhama-Espinosa (2010). Mind, Brain, and Education Science: A Comprehensive Guide to the New Brain-Based Teaching. W.W. Norton & Company. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-393-70607-9.

Alhazen (or Al-Haytham; 965–1039 CE) was perhaps one of the greatest physicists of all times and a product of the Islamic Golden Age or Islamic Renaissance (7th–13th centuries). He made significant contributions to anatomy, astronomy, engineering, mathematics, medicine, ophthalmology, philosophy, physics, psychology, and visual perception and is primarily attributed as the inventor of the scientific method, for which author Bradley Steffens (2006) describes him as the "first scientist".

- ^ Ackerman, James S. (1978). "Leonardo's Eye". Journal of the Warburg & Courtauld Institutes. 41: 119. doi:10.2307/750865. JSTOR 750865.

- ^ Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, Paperback – 9 November 2004, p. 257

- ^ Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, Paperback – 9 November 2004, p. 296

- ^ "Which country has the best brains?". BBC News. 8 October 2010. Retrieved 6 December 2011.

- ^ Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, Paperback – 9 November 2004, p. 284

- ^ Charles Murray, Human Accomplishment: The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950, Paperback – 9 November 2004, p. 252

- ^ Wiser, Wendell H. (2000). Energy resources: occurrence, production, conversion, use. Birkhäuser. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-387-98744-6.

- ^ Augustus Heller (2 April 1896). "Anianus Jedlik". Nature. 53 (1379): 516. Bibcode:1896Natur..53..516H. doi:10.1038/053516a0.

- ^ Tom McInally, The Sixth Scottish University. The Scots Colleges Abroad: 1575 to 1799 (Brill, Leiden, 2012) p. 115

- ^ Bedell, Frederick (1942). "History of A-C Wave Form, Its Determination and Standardization". Transactions of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. 61 (12): 864. doi:10.1109/T-AIEE.1942.5058456.

- ^ Freebert, Ernest (2014). The age of Edison : electric light and the invention of modern America. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-312444-3.

- ^ Ralph Stein (1967). The Automobile Book. Paul Hamlyn Ltd

- ^ Diesel's Rational Heat Motor by Rudolph Diesel

- ^ Fermi, Enrico (December 1982). The First Reactor. Oak Ridge, Tennessee: United States Atomic Energy Commission, Division of Technical Information. pp. 22–26.

- ^ Coe, Lewis (1995). The Telephone and Its Several Inventors: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7864-2609-6.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court". Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ John F. Mitchell Biography

- ^ Who invented the cell phone?

- ^ "IPTO – Information Processing Techniques Office", The Living Internet, Bill Stewart (ed), January 2000.

- ^ National Research Council (U.S.). Committee on the Future of the Global Positioning System; National Academy of Public Administration (1995). The global positioning system: a shared national asset: recommendations for technical improvements and enhancements. National Academies Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-309-05283-2. Retrieved 16 August 2013., https://books.google.com/books?id=FAHk65slfY4C&pg=PA16

- ^ Extraterrestrial Relays

- ^ "Philo Taylor Farnsworth (1906–1971)", The Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Collingridge, M. R. et al. (2007) "Ink Reservoir Writing Instruments 1905–20" Transactions of the Newcomen Society 77(1): pp. 69–100, p. 69

- ^ "Cathode Ray Tube and its Applications". International Journal of Innovative Research in Technology. 1.

- ^ Jonathan W. Steed; Jerry L. Atwood (2009). Supramolecular Chemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. p. 844. ISBN 978-0-470-51234-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Losev, O.V. (1928). "CII. Luminous carborundum detector and detection effect and oscillations with crystals". The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 6 (39): 1024–1044. doi:10.1080/14786441108564683.

- ^ Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A Concise History of Photography (3rd ed.). Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-486-25128-8.

- ^ Schiffer, Michael B.; Hollenback, Kacy L.; Bell, Carrie L. (2003). Draw the Lightning Down: Benjamin Franklin and Electrical Technology in the Age of Enlightenment. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 242–44. ISBN 978-0-520-23802-2.

- ^ * Elwes, Richard, "An enormous theorem: the classification of finite simple groups," Plus Magazine, Issue 41, December 2006.

- ^ Richard Swineshead (1498), Calculationes Suiseth Anglici, Papie: Per Franciscum Gyrardengum.

- ^ Dodge, Y. (2006) The Oxford Dictionary of Statistical Terms, OUP. ISBN 0-19-920613-9

- ^ Archimedes, Method, in The Works of Archimedes ISBN 978-0-521-66160-7

- ^ The Oxford english dictionary (2nd. ed.). London: Claredon Press. 2001. ISBN 978-0-19-521942-5.

- ^ Kline, Morris (1972). Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times, Vol. 3. Oxford University Press. pp. 1122–1127. ISBN 978-0-19-506137-6.

- ^ Croom, Fred H (1989). Principles of Topology. Saunders College Publishings. pp. 1122–27. ISBN 978-0-03-029804-2.

- ^ Lauwers, Luc; Willekens, Marleen (1994). "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (PDF). Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management. 39 (3): 289–304 [p. 300]. ISSN 0772-7674.

- ^ (Chapters 9, 10, 11, 13, 25 and 26) and three times (Chapters 4, 8 and 19) in its sequel, Equality

- ^ Humble, Richard (1978). The Seafarers – The Explorers. Alexandria, Virginia: Time-Life Books.

- ^ Orloff, Richard W. (September 2004) [First published 2000]. "Table of Contents". Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. NASA SP-2000-4029. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Nelson, Jon. "Mars Exploration Rover – Spirit". NASA. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Nelson, Jon. "Mars Exploration Rover -Opportunity". NASA. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ Worth, Helen (28 February 2001). "The End of an Asteroidal Adventure: NEAR Shoemaker Phones Home for the Last Time". Applied Physics Lab.

- ^ Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Buckley, Mike; Stotoff, Maria (14 July 2015). "15-149 NASA's Three-Billion-Mile Journey to Pluto Reaches Historic Encounter". NASA. Retrieved 14 July 2015.

- ^ Butrica, Andrew. From Engineering Science to Big Science. p. 267. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Weber, Johannes (2006). "Strassburg, 1605: The Origins of the Newspaper in Europe". German History. 24 (3): 387–412 (387). doi:10.1191/0266355406gh380oa.:

At the same time, then as the printing press in the physical technological sense was invented, 'the press' in the extended sense of the word also entered the historical stage. The phenomenon of publishing was now born.

- ^ Hardy, Jonathan (25 February 2010). Western Media Systems. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-135-25370-7.

- ^ Hardy, Jonathan (25 February 2010). Western Media Systems. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-135-25370-7.

- ^ Küng, Lucy; Picard, Robert G.; Towse, Ruth (14 May 2008). The Internet and the Mass Media. SAGE. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-4462-4566-8.

- ^ Langmuir, Gavin I. (8 May 1990). History, Religion, and Antisemitism. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91226-7.

- ^ Nirenberg, David (4 February 2013). Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05824-6.

- ^ Yivo Institute for Jewish Research (2005). Kertzer, David I. (ed.). Old demons, new debates : anti-Semitism in the West. Teaneck, NJ: Holmes & Meier Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8419-1439-1. OCLC 58975776.

- ^ Nirenberg, David (2013). Anti-Judaism : the Western tradition (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-05824-6. OCLC 783163429.

- ^ Maccoby, Hyam (2006). Antisemitism and modernity : innovation and continuity. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-31173-1.

- ^ "Religiously Unaffiliated". Pewforum.org. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Census 2011 religion data reveal there are 4 m fewer Christians and 1 in 4 is now an atheist | Mail Online. Dailymail.co.uk (13 December 2012). Retrieved on 2013-07-19.

- ^ "Germany". State.gov. 14 September 2007. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Views on globalisation and faith Archived 17 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ipsos MORI, 5 July 2011.

- ^ Template:Fr Catholicisme et protestantisme en France: Analyses sociologiques et données de l'Institut CSA pour La Croix – Groupe CSA TMO for La Croix, 2001

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2007". 14 September 2007. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ a b c ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global Christianity". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ "Europe". Pewforum.org. 19 December 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "Christians". Pewforum.org. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Americas". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ ANALYSIS (19 December 2011). "Global religious landscape: Christians". Pewforum.org. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF), Special Eurobarometer, 393, European Union: European Commission, p. 233, 2012, retrieved 14 August 2013 The question asked was "Do you consider yourself to be...?" With a card showing: Catholic, Orthodox, Protestant, Other Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu, Atheist, and Non-believer/Agnostic. Space was given for Other (SPONTANEOUS) and DK. Jewish, Sikh, Buddhist, Hindu did not reach the 1% threshold.

- ^ "Discrimination in the EU in 2012" (PDF). Special Eurobarometer. 383: 233. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

Sources

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Global communication wi5thout universal civilization. INU societal research. Vol. Vol. 1: Coexisting contemporary civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 978-2-88155-004-1.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barzun, Jacques From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life 1500 to the Present HarperCollins (2000) ISBN 0-06-017586-9.

- Daly, Jonathan. "The Rise of Western Power: A Comparative History of Western Civilization" (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2014). ISBN 978-1441161314.

- Daly, Jonathan. "Historians Debate the Rise of the West" (London and New York: Routledge, 2015). ISBN 978-1138774810.

- Jones, Prudence and Pennick, Nigel A History of Pagan Europe Barnes & Noble (1995) ISBN 0-7607-1210-7.

- Merriman, John Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Present W. W. Norton (1996) ISBN 0-393-96885-5.

- Derry, T. K. and Williams, Trevor I. A Short History of Technology: From the Earliest Times to A.D. 1900 Dover (1960) ISBN 0-486-27472-1.

- Eduardo Duran, Bonnie Dyran Native American Postcolonial Psychology 1995 Albany: State University of New York Press ISBN 0-7914-2353-0

- McClellan, James E. III and Dorn, Harold Science and Technology in World History Johns Hopkins University Press (1999) ISBN 0-8018-5869-0.

- Stein, Ralph The Great Inventions Playboy Press (1976) ISBN 0-87223-444-4.

- Asimov, Isaac Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology: The Lives & Achievements of 1510 Great Scientists from Ancient Times to the Present Revised second edition, Doubleday (1982) ISBN 0-385-17771-2.

- Pastor, Ludwig von, History of the Popes from the Close of the Middle Ages; Drawn from the Secret Archives of the Vatican and other original sources, 40 vols. St. Louis, B. Herder (1898ff.)

- Walsh, James Joseph, The Popes and Science; the History of the Papal Relations to Science During the Middle Ages and Down to Our Own Time, Fordam University Press, 1908, reprinted 2003, Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-3646-9 Reviews: p. 462.[2]

- Ankerl, Guy (2000). Coexisting Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INUPRESS, Geneva, 119–244. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Atle Hesmyr (2013). Civilization, Oikos, and Progress ISBN 978-1468924190

- Hanson, Victor Davis; Heath, John (2001). Who Killed Homer: The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom, Encounter Books.

- Stearns, P.N. (2003). Western Civilization in World History, Routledge, New York.

- Thornton, Bruce (2002). Greek Ways: How the Greeks Created Western Civilization, Encounter Books.

Further reading

- Barzun, Jacques. From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life : 1500 to the Present. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

External links